Walter Booth: Pioneer of British Science Fiction Film

Last week, I talked about the Spanish master of silent film, Segundo de Chomón. This week, I’d like to talk about another early genre filmmaker who has also been all but forgotten.

Walter R. Booth was an English stage magician who teamed up with film pioneer Robert W. Paul, who was making and screening films as early as 1896 at London’s Egyptian Hall, where Booth did his magic act. In 1899, Booth and Paul co-founded Paul’s Animatograph Works, a production house that specialized in trick films using Paul’s technical know-how and Booth’s skill at magic and illusion. These short films wowed audiences with special effects such as animation, split screen, jump cuts, superimposition, multiple exposures, and stop motion animation.

Their earliest surviving film is believed to be Upside Down, or The Human Flies (1899), which uses a simple trick to make it appear that the audience of a magic show are dancing on the ceiling. In 1900, they pioneered the use of scale models to make A Railway Collision. While the effect is crude to modern eyes, they do manage to create a sense of mounting suspense.

The next year, the duo made a more ambitious magic show with The Waif and the Wizard. Here a magician befriends a poor little boy who helps him with his act. The magician then saves the boy’s family from an evil landlord. People and objects are made to appear and reappear with remarkably smooth jump cuts. Film historians believe that the magician in both films was Booth himself. It must have been satisfying to perform magic tricks on film that would be impossible on stage.

The year 1901 also saw the production of The Magic Sword, a fantasy tale in which our hero has to save the damsel in distress by fighting various special effects. At nearly three minutes, it was a fairly long film for that year. Another film of epic length was the three-and-a-half minute Marley’s Ghost, the first film adaptation of Dickens’ A Christmas Carol.

Booth and Paul continued to collaborate until 1906, the year that saw two of their best films. Is Spiritualism a Fraud? shows a medium performing a seance with some spooky special effects, and then getting his comeuppance with some good old fashioned slapstick. The oddly named The ‘?’ Motorist follows a car as it runs down a cop and flies into the air to drive around the solar system.

That year saw the end of their collaboration, with Booth moving to the Charles Urban Trading Company. Urban was one of the first to film news events such as soldiers embarking for the Boer War, as well as scientific films, including shooting footage through a microscope. He also invented the first color film system in 1908.

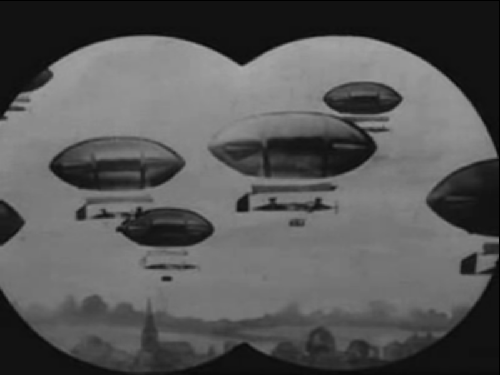

Urban hired Walter Booth to make fictional films and he came out with a series of trick shorts, including his most enduring film, The Airship Destroyer (1909), which shows a fleet of airships bombarding England. Our hero has an “aerial torpedo” (basically a drone) and uses it to defend King and Country. The film was remarkably prescient in that only a few years later, German zeppelins would bomb England. The film was re-released during the war as a propaganda piece. He followed up The Airship Destroyer with The Aerial Submarine (1910) and The Aerial Anarchists (1911), creating perhaps the first film trilogy.

These were some of the last fictional films Booth would make. He soon switched to making advertising pictures until his death in 1938.

Like with most early silent films, these movies are generally less than six minutes long, perfect for a quick break from work. Click on the links to see them. Enjoy!

Sean McLachlan is a freelance travel and history writer. He is the author of the historical fantasy novel A Fine Likeness, set in Civil War Missouri, and the post-apocalyptic thriller Radio Hope. His historical fantasy novella The Quintessence of Absence, was published by Black Gate. Find out more about him on his blog and Amazon author’s page.

All images in the public domain.

We’re so jaded today, bored in the knowledge that CGI can literally show us anything. That makes these dawn-age films all the more precious; in the right frame of mind, it’s like being present at the creation. With some sympathetic imagination, it’s as if you’re sitting right there with the first audience, marveling at these amazing things that no one has ever seen before.

[…] you like silent film, you might like my posts on silent fantasy masters Walter Booth and Segundo de […]

[…] you like silent film, you might like my posts on silent fantasy masters Walter Booth and Segundo de Chomón, and one on real outlaws in silent […]