Hearing the Voices of Dead Authors in the Present Tense

There are a number of citation styles for a variety of fields, but the two biggies are MLA (Modern Language Association) and APA (American Psychological Association). The latter is used in the natural sciences and research fields. The former is used in the humanities — literature, philosophy, visual and performing arts — so it’s the one I grew intimately familiar with while earning my bachelor’s and master’s degrees in English Literature and Language.

There are a number of citation styles for a variety of fields, but the two biggies are MLA (Modern Language Association) and APA (American Psychological Association). The latter is used in the natural sciences and research fields. The former is used in the humanities — literature, philosophy, visual and performing arts — so it’s the one I grew intimately familiar with while earning my bachelor’s and master’s degrees in English Literature and Language.

MLA is also the one I primarily taught my first-year composition students during my nine years as an English instructor (which, in retrospect, was a bit of a disservice to all the kids who were going on to pursue non-humanities degrees). In my defense, it is the style primarily used in high school, so it is the one that most students entering college have some degree of familiarity with — which is strange when you think about it: it’s as if our secondary-school system assumes most students will go on to pursue degrees in theater or English. The way I couched my presentation of MLA went something like this: “Whatever field you go into, you will have to write papers that follow a particular formatting and style guide. It may not be this one — it may be APA or Chicago — but using this one will get you accustomed to using one.”

In recent years, I’ve had to get more familiar with APA because I do a fair amount of copy-editing on the side for education, sociology, and psychology professors who write their chapters and academic papers in APA style. The differences between the styles are myriad — each one, after all, has its own labyrinthine manual of hundreds of rules in small type (with sometimes counter-intuitive indexing — as anyone who has spent wasted minutes vainly searching for the guideline pertaining to this one particular set of circumstances knows). Whatever the differences in details, though, their main purpose is to provide a consistent way for other scholars to easily locate the sources one has cited.

There is, however, one difference between MLA and APA style that strikes me as huge: indicative of a significant difference in worldview, even. It involves tense. APA prefers past tense. MLA prefers present tense.

So, according to APA:

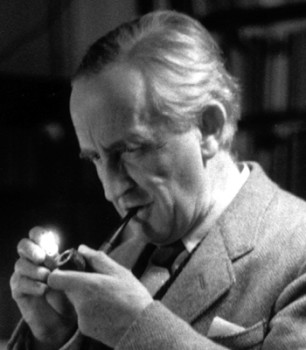

Tolkien (1947) said, “Fantasy, the making or glimpsing of Other-worlds, was the heart of the desire of Faërie.”

According to MLA:

J.R.R. Tolkien says, “Fantasy, the making or glimpsing of Other-worlds, was the heart of the desire of Faërie” (“On Fairy-Stories”).

APA wants to locate that statement at an exact historical moment, and it’s very clear that Tolkien said it long ago and that he’s also dead.

MLA doesn’t even give a date in the in-text citation (you can go to the Works Cited if you really want to find that out). As far as MLA is concerned, Tolkien said it; he’s been saying it; he’s still saying it right now. And what do you have to say to that, hmm?

MLA doesn’t even give a date in the in-text citation (you can go to the Works Cited if you really want to find that out). As far as MLA is concerned, Tolkien said it; he’s been saying it; he’s still saying it right now. And what do you have to say to that, hmm?

Here’s the thing. I’ve always fancied that my life as a reader — long before that love drew me into the world of academia — brought me into contact with all sorts of people from all sorts of times and places. I have fancifully noted that when I curl up in my armchair by the fire, pour a glass of bourbon, and light my pipe, I am about to hang out with Homer (or the conglomeration of anonymous writers who became the mythical Homer), Virgil, Shakespeare, Chaucer. I am going to hold forth with Melville, chuckle at the wisecracks of Twain still hitting their marks from another century and beyond the grave. I am going to be allowed into that private upstairs room where Dickinson lived a richly imaginative life as a recluse, staring at the world through that window, but also through her amazing eyes.

These authors — or the part of them that was embodied by the thoughts they committed to paper — are immortal, at least as long as we continue to read them. And through the agency of the written word, they are able to continue their participation in the Great Ongoing Conversation that we have ourselves now joined in on; they are able to make their contributions of Story and Song to the World’s Campfire at which we have now taken a seat. We hang out with their ghosts. That thought has always thrilled me, and left me a little awed by the wonder of it.

And MLA acknowledges that. Indeed, MLA foregrounds it in the very way it requires us to quote from those authors.

APA is all about the empirical data; I get that. It doesn’t even want you to list an author’s first name — what’s important is what the claim was or what the research found, when it happened, and whether it is still accurate or has been superseded by more recent research.

But MLA, it appeals to the imagination. In my field, when I open up a book, J.R.R. Tolkien is just as present as George R.R. Martin. Samuel Taylor Coleridge can be sitting on one side transporting me to numinous heights of Romanticism while Billy Collins on the other side regales me with his homespun humor gleaned from observations of the mundane.

For me, they’re all in the present tense. And — whatever citation style you use — you can quote me on that.

While there is something to what you write regarding the use of the title vs. the use of date, but…and you knew there was a but right?…it make indexing a works cited much easier to write to organize by date. It also provides a history of an idea in an interesting way, especially with translated works. It allows researchers to see how timeframe might influence the translation of a term that Aristotle used etc.

I actually think both support the Machiavellian – and not in the typical sense, rather in the sense he uses in his Discourses on Livy – sense of timeless dialogue that you present the MLA as engendering.

All of that said, I want to reiterate the importance of avoiding the fallacy that “just because someone wrote something 2500 years ago it’s dumb.”

Lovely! I’ll be pointing my students to this essay.

Christian: “avoiding the fallacy that ‘just because someone wrote something 2500 years ago it’s dumb.'”

Amen to that! Plato, Aristotle, Socrates — while we may have disagreements with them, some of their observations have never been articulated better. And philosophers, politicians, and poets still contend with them, even if to disagree. They’re as relevant to the conversation today as they were 2400 years ago.

Sarah,

Thank you! It’s always gratifying to have one’s work considered in the classroom.