Hell to Pay: The Devil and Daniel Webster in Print and on Film

Is there any place more melancholy than the graveyard of forgotten writers? While the reputations of even major literary figures can wax and wane, for genuinely innovative or influential authors, critical rebounds, if not assured, are at least possible. (Hemingway, anyone?)

Is there any place more melancholy than the graveyard of forgotten writers? While the reputations of even major literary figures can wax and wane, for genuinely innovative or influential authors, critical rebounds, if not assured, are at least possible. (Hemingway, anyone?)

But permanent eclipse seems to be the fate of the facile, ambitious middlebrow who was highly popular and overpraised during his or her prime. Once this kind of writer is no longer around to hold the stage with new work, a spell seems to be broken and often a speedy and ruthless (if not embarrassed) re-evaluation occurs, resulting in a quick trip to oblivion and a complete disappearance from the public consciousness. John O’Hara, Dorothy Parker, Irwin Shaw — where are you now? Often it’s not even a matter of an “official” verdict by the critical establishment — it’s simply that a few years pass and no one reads the writer anymore.

One victim of this kind of reaction was Stephen Vincent Benét. A prolific producer of poetry and fiction from the 1920’s up until his death from a heart attack in 1943, Benét was both highly regarded by critics and popular with the wider public. His epic narrative poem of the American Civil War, John Brown’s Body, won the Pulitzer Prize in 1929, and there was a time when countless readers were familiar with his widely-anthologized story “The Devil and Daniel Webster,” a bit of nostalgic, patriotic Americana that blends history, the tall tale, and the supernatural into a fluent and beguiling concoction.

Published in 1936, “The Devil and Daniel Webster” tells the story of one Jabez Stone, a hard-working but struggling New Hampshire farmer. “He wasn’t a bad man to start with, but he was an unlucky man. If he planted corn, he got borers; if he planted potatoes, he got blight. He had good-enough land, but it didn’t prosper him; he had a decent wife and children, but the more children he had, the less there was to feed them.”

[Click on images to embiggen.]

After a run of particularly bad luck, Stone declares, “I vow it’s enough to make a man want to sell his soul to the devil! And I would, too, for two cents!” The farmer immediately hopes that his reckless vow will go unnoticed, but for statements like that, “notice is always taken, sooner or later,” and, being a New Hampshireman, Jabez will not take a promise back, no matter how rash.

The next day, “a soft-spoken, dark-dressed stranger” drives up to the Stone farmhouse and asks for Jabez. The two quickly conclude a bargain — seven years of prosperity and good fortune in exchange for the soul of Jabez Stone. The deal is finalized when the stranger pricks Jabez’s finger with a silver needle (“The wound healed clean, but it left a little white scar”) and Stone signs the contract with his blood.

The stranger is as good as his word; Jabez Stone’s luck turns immediately, and soon he is the most prosperous and successful farmer in the region. But as the end of the seven year term approaches, Jabez begins to have second thoughts, especially as the sixth year ends and the stranger begins to pop in for frequent visits, as if to check on the condition of his merchandise. On one of these visits, as the stranger is pulling Stone’s contract out of his pocketbook (Jabez has expressed some doubts as to the document’s legality), something briefly flutters free:

It was something that looked like a moth, but it wasn’t a moth. And as Jabez Stone stared at it, it seemed to speak to him in a small sort of piping voice, terrible small and thin, but terrible human. “Neighbor Stone!” it squeaked. “Neighbor Stone! help me! For God’s sake, help me!”

It is the soul of Miser Stevens, a well-known local character; “spry and mean as a woodchuck” a few days before, all the miser has and all he is are now in the possession of the stranger. “‘These long-standing accounts,’ said the stranger with a sigh; ‘one really hates to close them. But business is business.'” Jabez is now in real terror, and convinces the stranger to give him a three year extension of his contract. “But till you make a bargain like that, you’ve got no idea of how fast four years can run.”

Just a few days before the extension runs out, a panicked Stone goes to see the great statesman (and his near neighbor) Daniel Webster to ask for his help. Benet depicts the senator as a sort of political Paul Bunyan:

They said, when he stood up to speak, stars and stripes came right out in the sky, and once he spoke against a river and made it sink into the ground. They said, when he walked in the woods with his fishing rod, Killall, the trout would jump out of the streams right into his pockets, for they knew it was no use putting up a fight against him; and when he argued a case, he could turn on the harps of the blessed and the shaking of the earth underground. That was the kind of man he was, and his big farm up at Marshfield was suitable to him. The chickens he raised were all white meat down through the drumsticks, the cows were tended like children, and the big ram he called Goliath had horns with a curl like a morning-glory vine and could butt through an iron door.

Even though he has “about seventy-five other things to do and the Missouri Compromise to straighten out,” Webster agrees to take the case. They return to Stone’s house and await the arrival of the stranger, due at midnight on the final day. When the stranger enters, Webster quickly sees that Mr. Scratch (“I’m often called that in these regions”) is not going to compromise, and even worse, legally speaking, the contract is all in order. As his opponent turns aside all of his arguments, Webster finally demands a trial by jury for his client: ‘”Let it be any court you choose, so it is an American judge and an American jury!” said Dan’l Webster in his pride. “Let it be the quick or the dead; I’ll abide the issue!'”

Mr. Scratch accepts the terms, and then convenes a ghostly jury of the damned, full of prominent traitors, murderers, pirates, and fanatics, topped off with a suitable judge, one Justice Hathorne. “He presided at certain witch trials once held in Salem. There were others who repented of the business later, but not he.”

The trial begins, and as Mr. Scratch presents his case, it soon becomes clear that the deck is stacked against Jabez Stone. All the court’s rulings go against him, and after the stranger finishes and Daniel Webster rises to present his client’s side, furious at the court’s crooked behavior and prepared to lash out, the senator realizes that

It was him they’d come for, and not only Jabez Stone. He read it in the glitter of their eyes and in the way the stranger hid his mouth with one hand. And if he fought them with their own weapons, he’d fall into their power; he knew that, though he couldn’t have told you how. It was his own anger and horror that burned in their eyes; and he’d have to wipe that out or the case was lost.

Knowing the stakes, Webster reigns in his fury and in an effort to awaken the decency that even the worst men once possessed, instead speaks softly to the jurors. He invokes the common humanity that all men share, even those who foolishly cast it away or allow it to be ruined; he speaks of the simple pleasures of living that everyone knows; he tells of the desire of all men to battle with life and improve their lot; and he celebrates the American land that gave them all birth, and that permitted them to aspire, to struggle, and even to fail:

And his words came back at last to New Hampshire ground, and the one spot of land that each man loves and clings to. He painted a picture of that, and to each one of that jury he spoke of things long forgotten. For his voice could search the heart, and that was his gift and his strength. And to one, his voice was like the forest and its secrecy, and to another like the sea and the storms of the sea; and one heard the cry of his lost nation in it, and another saw a little harmless scene he hadn’t remembered for years. But each saw something. And when Dan’l Webster finished he didn’t know whether or not he’d saved Jabez Stone. But he knew he’d done a miracle. For the glitter was gone from the eyes of judge and jury, and, for the moment, they were men again, and knew they were men.

When the jury returns from considering its verdict, it finds for Jabez Stone. Daniel Webster delivers a swift kick to the seat of Mr. Scratch’s pants, with the result that the devil “hasn’t been seen in the state of New Hampshire from that day to this. I’m not talking about Massachusetts or Vermont.”

When the jury returns from considering its verdict, it finds for Jabez Stone. Daniel Webster delivers a swift kick to the seat of Mr. Scratch’s pants, with the result that the devil “hasn’t been seen in the state of New Hampshire from that day to this. I’m not talking about Massachusetts or Vermont.”

“The Devil and Daniel Webster” is probably the only thing from Benét’s large output that is still read today, and even it is likely not all that familiar anymore. Its old-fashioned patriotic rhetoric and political mythmaking don’t sit particularly well with skeptical modern readers, but it’s still an enjoyable, eloquently told tale with many resonant moments, moments that are by turn stirring, humorous, and eerie. It’s full of memorable turns of phrase, and its vision of America is by no means as simplistic and uncritical as it may at first seem.

The bad luck of Jabez Stone undermines the self-satisfied narrative of a country where the belief is that hard work will inevitably be rewarded with success, and the frustrated farmer’s resort to such questionable aid as Mr. Scratch provides calls many of the nation’s optimistic assumptions about justice and equity into question. The dark, ambivalent view of the Republic implicit in the story is even more discernible in the rather neglected 1942 film version of the tale, which Benét co-scripted with Dan Totheroh.

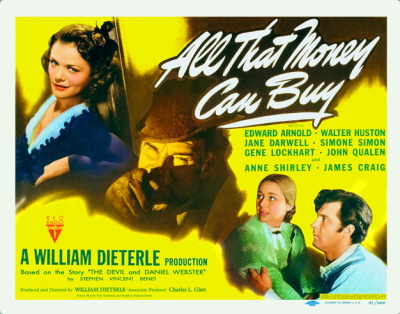

Produced for RKO, the film (originally released under the title All That Money Can Buy) was produced and directed by William Dieterle. Like so many who worked in Hollywood during the 30’s and 40’s, Dieterle was a European émigré, having come to the United States from Germany in 1930, where he had begun his career as an actor. He worked steadily in Hollywood for over twenty years, directing at least two films which have achieved classic status.

In 1935 he brought theatrical impresario (and old Berlin colleague) Max Reinhardt’s production of A Midsummer Night’s Dream to the screen, a film memorable for its over-the-top, wedding cake baroque style and eccentric casting (Mickey Rooney and Jimmy Cagney do Shakespeare — and do quite well), and in 1939 he directed one of the best-remembered films of that greatest of Hollywood years, The Hunchback of Notre Dame, starring Charles Laughton and Maureen O’Hara.

Fine as those films are, The Devil and Daniel Webster may be Dieterle’s most assured work. His style, influenced by his early work with some of the great names in German film during the glory days of German Expressionism, was well suited to a fable-like tale of good and evil.

Benét’s story lent itself perfectly to sharp visual contrasts of sun and shadow, of light and darkness, and Dieterle delivered a movie that is always visually engaging, and is full of bold images that perfectly illustrate the stark conflict at the heart of the story, from the bright, airy, sunlit streets of the community of Cross Corners on the day Daniel Webster is honored by its free and happy citizens, to the claustrophobically crowded, overheated, frenetic barn dance that Jabez holds to celebrate the birth of his son. In this scene, the light and space of Cross Corners is cancelled out by an oppressive darkness that is shot through with sudden stabs of light that serve to disorient rather than illuminate, while Mr. Scratch sits in the rafters with his violin, urging the celebrants on to Dionysian excess as he plays a violent tune that sounds like it was newly-minted in the lower depths to commemorate a demon’s christening. Many times the struggle between light and darkness is combined in a single image, as in the scene when the unlucky farmer first sees Mr. Scratch, and Jabez’s moment of decision is shown by having the upper half of his face in light and the lower half in shadow.

Dieterle’s assured direction is a major factor in the film’s success; such a diagrammatic story could have easily become static, but Dieterle’s ability to keep the film’s moods and images in mercurial motion prevents that. In this he was aided by a script that took the original story and carried it several steps further.

In outline, the story and the film tell tales that are almost identical, but the script expands and deepens Benét’s original, fleshing out the characters and adding illuminating incidents. There are only three real people in the short story — Daniel Webster, Jabez, and Mr. Scratch, and these three are characterized in the broad, flat strokes sufficient for a fable painted in primary colors. The film necessarily changes that and is thus able to engage us more deeply and bring out themes that were implicit or even nonexistent in the story.

James Craig’s Jabez feels thwarted and put-upon by life from the first moments of the film and after signing away his soul fifteen minutes in, he spends the rest of the movie (up until the last five minutes) in the grip of Mr. Scratch. During that time he becomes ever more ill-tempered, coarse, and brutal, and for this reason it is perhaps natural that he isn’t particularly likeable. We understand the frustration that led him to make his bargain, but still recoil from his increasingly abusive treatment of his wife and his cynical and exploitative dealings with the neighbors who were once his friends. Craig does fine by the character as written (he’s quite good at being sullen and surly, and the sick despair in his eyes as his time runs out does stir our sympathy), but in the film as in the story, Jabez mainly serves as the board upon which the two great opponents, Daniel Webster and Mr. Scratch, play their game of diabolical draughts.

Often Jabez’s corruption is conveyed cinematically as much as through Craig’s acting. In one of the film’s most chilling moments, Jabez and his wife are looking at the ruined fields after an unexpected hailstorm has destroyed everyone’s crops — everyone but Jabez’s. When his devastated neighbors walk by, Jabez calls out a callously cheery greeting: “Hello Lem — Hank!” and then he laughs — but instead of his own laugh, it is Scratch’s jeering cackle that emerges from his mouth, as the devil’s leering, gleeful face is superimposed over the scene.

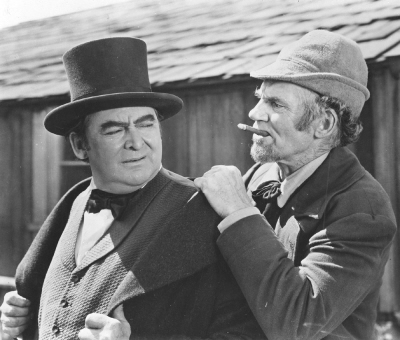

In stories where a good character confronts an evil one, the good one may win out on the page or on the screen, but frequently it’s the evil one who triumphs afterwards in memory, and that’s true of The Devil and Daniel Webster. Certainly the first thing almost everyone who knows the film thinks of is Walter Huston’s amazing performance as Mr. Scratch, but it must be said that Edwin Arnold comes in a very respectable second as Daniel Webster. A big, barrel-chested man, Arnold brings an imposing physical presence to the senator, in marked contrast to Huston’s slight, dapper demon. (The two do have affinities, though — they are both wordsmiths, persuaders, natural-born politicians.)

Arnold looks like a man built for oratory, and when he winds up the rhetoric and turns it loose in the courtroom scene, it is easy to believe that he could convince a jury convened from the ninth circle of hell. But even while embracing big gestures and big rhetoric, Arnold avoids coming across as phony or callously manipulative — we believe that Webster is honest and just and that he truly cares about Jabez and his family, and about all the American people.

We see Webster’s courage too, in the moment when Justice Hathorne (H.B. Warner, looking as if he actually had been dug up to play the part) warns him: “If you speak and fail to convince us, you too are doomed.” A sweating, shaken Webster takes a long moment to think it over, as judge and jury chant together, in an echoey, eerie whisper, “Lost and gone! Lost and gone! Dragged down with us! Lost and gone!”

Finally, Webster silences the chorus with a shouted, “Be still!” and then stands to make his plea — he will risk everything to cast his lot with Jabez Stone. Edwin Arnold gives us a politician, to be sure, but one for whom the profession is a call to noble service. That may have been easier to swallow in 1942 than it is now, but it is a measure of Arnold’s excellence that even today he can convince us of this man’s goodness and greatness.

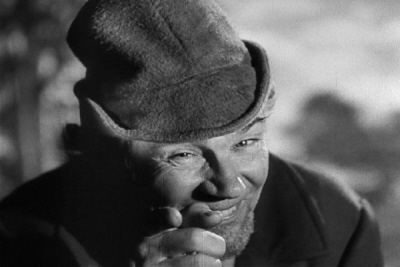

The devil is probably one of the most portrayed characters in film history (right up there with Abe Lincoln and Tarzan), and no one has ever done it better than Walter Huston did it here. He is greatly aided in this by his look — makeup and lighting emphasize his already goatish features (in fact, he sports a goatee for the part), and he makes a point of smiling with all of his teeth; sometimes it looks as if he has two full sets in there.

And smile he does, for he is a convivial, Yankee demon, happy to share a drink or a story, someone who’s comfortable sitting around the cracker barrel in the general store, swapping lies with his neighbors. (When he walks into the local tavern after the hailstorm that destroyed the crops, he says, “Hi boys, howdy — did you ever see such hail? Big as bowling balls out our way — broke all the windows and nearly killed the cat!”) He’s happy to pitch in wherever he’s needed, even playing the drum in Daniel Webster’s welcome parade, and he takes a civic-minded interest in local and national affairs.

And smile he does, for he is a convivial, Yankee demon, happy to share a drink or a story, someone who’s comfortable sitting around the cracker barrel in the general store, swapping lies with his neighbors. (When he walks into the local tavern after the hailstorm that destroyed the crops, he says, “Hi boys, howdy — did you ever see such hail? Big as bowling balls out our way — broke all the windows and nearly killed the cat!”) He’s happy to pitch in wherever he’s needed, even playing the drum in Daniel Webster’s welcome parade, and he takes a civic-minded interest in local and national affairs.

As he helps Webster on with his coat after a horseshoe-pitching contest, he generously offers the senator his political help: “I thought with the presidential election coming up, you might need some help, Mister Webster, sir.”

Webster isn’t interested: “I’d rather see you on the side of the opposition.”

“Oh, I’ll be there too!” Scratch replies. Nineteenth century or twenty first, some things never change.

Huston plays Scratch with a zest and good humor that are infectious; his jaunty walk and cheery wave are buoyant with the sheer joy of living. He appreciates good food, a good cigar, good liquor, and a beautiful sunset… and if, when push comes to shove, he is adamant about his property rights, who can blame him for that? Aren’t we all particular about what belongs to us? He is a sharp dealer — but isn’t that how America was made? He’s the soul (if you’ll pardon the expression) of reasonableness… until he’s squeezed all that he can out of you, and then, well, there’s no place for sentimentality in business.

Walter Huston won the Best Supporting Actor Oscar for his grizzled prospector in 1948’s The Treasure of the Sierra Madre, (directed by his son, John Huston) and it was well deserved, but his work in The Devil and Daniel Webster is fully as good — it is, in fact, one of the great performances in American movies. (And need I say that Huston’s Mr. Scratch is far better — more alluring, even! — than Jennifer Love Hewitt’s devil in 2003’s lobotomized modernization of the story, Shortcut to Happiness, a movie awful enough to irrefutably prove the existence of hell? Well, I guess I did say it.)

The Devil and Daniel Webster is a film of contrasts, opposites, and conjoined pairs — darkness and light, sowing and reaping, isolation and community, damnation and redemption, and if Craig, Arnold, and Huston give flesh to the minimally sketched male characters of Benet’s story, three women — Anne Shirley as Jabez’s wife Mary, Jane Darwell as his mother Ma Stone, and Simone Simon as the servant girl Belle — add a contrast that was less explicit in the original tale, that of the material (or carnal) versus the spiritual.

Jane Darwell’s solid, unflappable Ma Stone is devout in a no-nonsense way, and is always reminding her son that financial success and material prosperity are not the most important things in life, not that he pays her much heed. Jabez’s first boon after his bargain with Mr. Scratch comes in the form of a cache of Hessian gold that the tempter reveals under the floor of the Stone barn; when Ma sees it she is immediately suspicious — she intuitively understands that it’s tainted somehow, and will bring nothing but trouble.

Jane Darwell’s solid, unflappable Ma Stone is devout in a no-nonsense way, and is always reminding her son that financial success and material prosperity are not the most important things in life, not that he pays her much heed. Jabez’s first boon after his bargain with Mr. Scratch comes in the form of a cache of Hessian gold that the tempter reveals under the floor of the Stone barn; when Ma sees it she is immediately suspicious — she intuitively understands that it’s tainted somehow, and will bring nothing but trouble.

Mr. Scratch knows that there’s no dealing with her; he hears her coming when he’s talking to Jabez and immediately runs off: “That’s your mother — I find her rather difficult. Hardly the type for my sort of thing.” Jabez knows it too, and urges him out before his mother can come in and catch him with the visitor.

Ma has her opposite in the servant girl Belle, an “old friend” of Mr. Scratch that he sends to the Stones from “over the mountain” after the birth of Jabez’s son. (This is a major difference between the story and the film — here, the Stones have only one child, who is born during the course of the movie.)

Scratch places the sensuous, French-accented Belle into the Stone house to secure Jabez in his damnation. She brazenly flirts, cajoles, and seduces him away from Mary, and as Jabez’s son Daniel (named after Daniel Webster) grows, she uses disputes over the child’s upbringing as a lever to further separate husband and wife.

The lewd Belle is pure hell-born carnality; the first time Jabez sees her, she is kneeling before the fireplace with the flames and smoke behind her making it seem as if she’s just emerged from an inferno. She then stands right in front of Jabez and, her face just inches from his, gazes boldly in his eyes with a look that could not be more transparently challenging and inviting. Jabez instantly turns to water, as well he might. Of course, Ma immediately hates Belle.

Jane Shirley’s Mary represents the median between Ma and Belle; she is the intersection where the material and the spiritual meet and she is yet another battleground upon which the war for Jabez’s soul will be fought. Like Ma, Mary is reverent and churchgoing, and is more concerned with her family’s spiritual than with its material well-being. But she is a wife too, and loves Jabez physically as well as spiritually. The way Mary provides a bridge linking the carnal and the spiritual can be seen in one of the most extraordinary scenes in the movie.

It is the night of the day that Jabez has sold his soul. There are no fears or regrets yet — he is full of plans for the future, assured of the good luck that has evaded him for so long. As they lie in their separate beds, Jabez reassures his wife, who is disquieted by this sudden change in fortune, already sensing a corresponding change in her husband. “Mary, you just wait and see — this is just the beginning, just the beginning of everything. I’m going to be the biggest man in New Hampshire, and you’re going to be the wife of the biggest man.”

Then, hearing a dog bark outside, Jabez goes over to the window and looks out over the moonlit yard. “There’s a new moon, Mary,” Jabez says. “Yes, I know, Jabez,” she replies. “There’s hope and promise in it. Planting and promise, of good harvest to come.”

And at that moment, Jabez sees Mr. Scratch strolling across the yard, puffing on his ever-present cigar. The devil looks up at Jabez and gives him a jovial wave. The sight of his “benefactor” seems to spark something in Jabez. He slowly turns and looks at Mary, his face again half shadowed, half lit; Mary gazes back expectantly at her husband for a long moment, and then first his shadow and then his body fall across her.

They embrace as Bernard Hermann’s lyrical music swells, and the screen goes dark. Mr. Scratch has engendered the desire that will produce a child, a child that he will then use to bind Jabez even closer to himself. The devil thinks to use the beautiful Mary for his own ends, but she has an unsold soul of her own and will not give up her husband so easily.

Eventually Jabez will abandon his wife’s bed for Belle, who believes that the advantages are all on her side. Belle says as much on the night of the big party that Jabez throws in the new mansion he has built (Mary and Ma still live in the original farmhouse.) Jabez doesn’t realize that he’s now so despised that no one will come to his soiree. Mary decides to attend though, and when she arrives at the mansion, she finds only Belle there.

“You know that you’re in my house,” Belle says.

“I know — and you could show me the door. You would too, if you weren’t still hoping the guests might arrive,” Mary replies, and then Belle makes the nature of her hold over Jabez explicit, or as explicit as it could be made in 1942.

“You think you’re so smart, Mrs. Stone,” she taunts. “You think Jabez will be lonely and you can be near him again. Looks like your big chance tonight — but you’re wrong. You can’t win him back — that way.”

“That’s my problem,” Mary returns.

Shortly afterward, we see how her seemingly insoluble problem is solved. There is a greater power than the material, sexual power that Belle exerts, and it emerges when Mr. Scratch overplays his hand by threatening the child that the desire — and the love — of Jabez and Mary produced. He offers Jabez a new deal, on one condition – that he surrender his son to Mr. Scratch.

Jabez refuses, even if it means his immediate damnation. Scratch gives him until midnight to reconsider, and it is this menace to his son that prompts Jabez to go Daniel Webster for help and brings about the story’s climax. If the desire that produced the child was corrupt, the child himself is not — or not yet — and the love that Jabez feels for him is still a living part of the love that he had for his wife, and for the hard but decent life that he lived before he met the devil, the life that he would now give anything — except his child — to return to.

When he tries to protect his son’s soul, Jabez finally rejects all the material benefits that Mr. Scratch can offer. But this clean American life that Jabez Stone wants to preserve for his child and regain for himself — it looks good from hell’s doorstep, but is it really as idyllic as it seems?

At first glance, The Devil and Daniel Webster looks like a flag-waving celebration of all things American, but only if we stay on the surface. Underneath, the America of the film is an America of limitless opportunity — unless you happen to be unlucky. It is a land of friendly, close-knit communities where people help each other — the obligatory form of address is “neighbor.”

But some of those neighbors cheat and exploit their less fortunate countrymen. It is a land of law and justice, but sometimes the law upholds ruthless usurers and offers no protection to those who have been compelled to sign their crooked but legal contracts. It is a place where honor, freedom, and the bonds of faith, family, and society flourish — until they’re debased and destroyed by materialism and the love of money. It is a land with a glorious history and heritage of liberty — except for the parts of that history and heritage that are violent, dishonest, and shameful.

When Webster is scrambling for a way to save Jabez Stone, a telling exchange occurs. “Mr. Stone is an American citizen, and an American citizen cannot be forced into the service of a foreign prince,” he declares. “Foreign? Who calls me a foreigner?” Scratch asks. “I never heard of the dev — er, I never heard of you claiming American citizenship,” the senator returns, and Scratch answers with words that are virtually identical in both the story and the film:

And who has a better right? When the first wrong was done to the first Indian, I was there. When the first slaver put out for the Congo, I stood on the deck. Am I not still spoken of in every church in New England? It’s true the North claims me for a southerner, and the South for a northerner, but I am neither. To tell the truth, Mr. Webster, though I don’t like to boast of it, my name is older in the country than yours.

A land that can claim both Mr. Scratch and Daniel Webster for native sons is a decidedly mixed place, neither all one thing nor all the other.

It takes Webster a while to come to terms with this, assuming as he did that asking for an American judge and jury was the same as asking for honor, decency, and fairness. Mr. Scratch knows better, and when he introduces the jury, the counsel for the defense is appalled — especially when he sees Benedict Arnold among the twelve. “A jury of the damned,” Webster gasps. “Dastards, liars, traitors, knaves,” Mr. Scratch readily admits. “This is monstrous,” Webster objects, but the devil has an unanswerable retort. “Americans all.”

The jury that so disturbs the orator is composed of citizens of a real America, not an ideal one. The ideal exists — but it does not exist not alone or unchallenged.

The ideal America of the film is a communitarian one, where fair play rules, neighbors work together for the good of all, and blessings and burdens are shared, but this ideal is constantly being attacked by the forces of selfishness and isolation. Just before he makes his deal with the devil, Jabez is ready to join the grange, a kind of farmer’s association, created for common support.

He abandons the notion as soon as Mr. Scratch dangles the Hessian gold in front of him. At the beginning of the movie Jabez is a victim of Miser Stevens (John Qualen), who is himself a client of Mr. Scratch (Stevens has a strongbox full of coins identical to the ones that Jabez has been baited with.)

But by the time of the party, Jabez is as ruthless a loan shark as the miser ever was, and Stevens is the only person who can stand to be in his presence; they are two miserable peas in the same pod — rich, yes, but also lonely, hated, and utterly isolated. Besides the miser, the only “people” to come to the party are Belle’s friends from “over the mountain,” lost, famished souls briefly released from hell to see “how fine Jabez Stone lives these days.” After whispering “Hooray for Jabez Stone” in their dead, papery voices, they grab handfuls of food from the banquet tables, briefly dance at Belle’s instigation, and then vanish into the night. This is all the society Jabez Stone’s bargain has left him — the despised and the dead. Such isolation is surely a foretaste of hell.

Daniel Webster’s courtroom victory frees the farmer’s soul and reestablishes the communal ideal, as Jabez destroys the extortionate contracts that he holds over his neighbors and everyone sits down to a big New Hampshire feast. But the last word is not given to the senator. The film concludes with Mr. Scratch down the road a piece, enjoying a pie he has stolen from Ma Stone’s kitchen.

He then takes out his pocketbook, and leafing through the pages on which he has recorded the names of his clients, starts looking around for a new prospect ripe for his approach. His gaze wanders around the frame until he seems to notice us. He arches his eyebrows, smiles that many-toothed smile, and points directly at us with a look that says, “And what about you?”

Jabez Stone has been saved from his folly and Cross Corners, New Hampshire, is quiet for now, but Mr. Scratch is still at large, and “money, and all that money can buy” remain potent tools of division and isolation. America is not yet its own ideal; the battle to make it so still has to be fought and won, one soul at a time.

The Devil and Daniel Webster is a very fine film, but it’s not a perfect one. The main fault is Jabez’s continual oscillation between wallowing in his sin and then reaching for repentance and slipping back again. This was likely intended to show the manic swings of a desperate man alternately struggling against his damnation and surrendering to it, but the changes too often seem unprepared for, and the effect is to make Jabez seem an inconsistent character.

This is a small complaint in a film of so many virtues, however, and it would be remiss to conclude without mentioning one of most outstanding of those virtues — the vibrant, exciting score, alternately lyrical and macabre, by Bernard Hermann.

Hermann is familiar to fans of fantastic film through his scores for The Day the Earth Stood Still, The Seventh Voyage of Sinbad, Jason and the Argonauts, and Mysterious Island, and for many episodes of The Twilight Zone. (Oh yes, he also did the music for a little something called Citizen Kane.)

During his long career he was nominated for several Oscars for his film music, but the only movie he won for was The Devil and Daniel Webster.

Not all forgotten authors deserve to be forgotten, and not every neglected film deserves to be neglected. Stephen Vincent Benét is unlikely to have a major revival at this late date, but neither has he earned the oblivion into which he has fallen, and I would hope that in these sesquicentennial years of the Civil War, someone is reading John Brown’s Body; it remains a very impressive work.

As for The Devil and Daniel Webster, both story and film are getting long in the tooth now, but they suffer little for it. They will amply reward the time invested in reading or viewing, both by providing entertainment and by provoking thought about the meaning of this gloriously mixed and contradictory temptation called America.

I never read the book, but I enjoyed the film. Like you say, Huston is a stand-out – I still remember that ‘maybe you’ scene at the very end! The story/film is parodied in ‘The Simpsons’. I think Homer sells his soul for a doughnut and Bart defends him. The devil turns out to look just like Ned Flanders.

I remember that Simpsons episode now, though I’d forgotten it until you mentioned it. “The Devil and Daniel Webster” might be one of those works that are more familiar in parody than in their original form.

I read this story in some anthology or another of American literature when I was young. I liked it, although I had the weird conception it was written much earlier than when you date it.

I saw the movie on WPIX (channel 11) in NYC some years later…

Princejvstin, I think Benet was consciously trying for an “older feel” to the story, so you were just picking up on the author’s intentions.

[…] Text Image: https://www.blackgate.com/2014/09/07/hell-to-pay-the-devil-and-daniel-webster-in-print-and-film/ […]