Ancient Worlds: Everything You Learned About the Epic of Gilgamesh – and Promptly Forgot

Vengeful goddesses. Rad bromances. Quests for eternal life. Sex, sex, and more sex…

Sounds like The CW, right? Instead, it’s what is likely the earliest surviving piece of literature we have: the Epic of Gilgamesh.

First written in the 18th century BCE, and composed in its present form probably sometime in the 13th century BCE, Gilgamesh was lost to us until 1853, when its tablets were discovered in Ninevah.

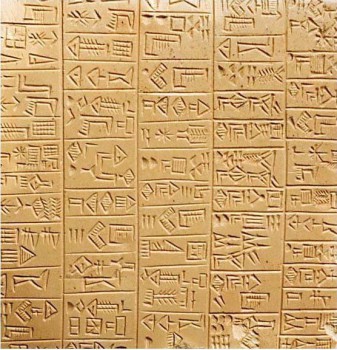

That’s right: tablets. Ancient Mesopotamian texts were inscribed by a wedge-shaped stylus onto wet clay tablets. (Bring that out the next time someone starts up the paper vs digital book argument.) And a good thing, too: had the epic been inscribed on parchment, it would be long gone.

But while the text itself was lost to us for millennia, the story left its traces behind. Once the Epic of Gilgamesh was discovered, we could see its fingerprints all over ancient myth and literature, from the Book of Genesis to the Illiad.

As I said, Gilgamesh was inscribed into tablets by wedge-shaped tools. Because of this triangular shape, the form of writing is called cuneiform and was used to record several languages, including Assyrian and Akkadian.

Gilgamesh was most likely a historical king who ruled over the Sumerian city of Uruk in the 27th century BCE. But we have no idea, beyond this basic fact, what the overlap between the historical figure and the mythological one was. Nearly six-thousand years has all but erased his true history.

But the legend survived. The Epic of Gilgamesh tells of a young king who behaved as a tyrant, abusing his people to such an extent that they prayed to their gods for help. That help came in the form of a man, Enkidu, who was strong enough to be Gilgamesh’s match. When they met, they fought, and when Gilgamesh bested Enkidu, they became best of friends. And quite possibly more. Together, they start to cause so much trouble that Ishtar makes them her personal target and the gods decree that one of them must die.

That lot falls to Enkidu. Gilgamesh is so overwhelmed by the loss of his friend that he abandons his kingdom and goes on a quest to find a way to live forever. He does this by consulting the oldest man in the world, Utnapishtim. Utnapishtim had been granted immortality by the gods after surviving a flood that wiped out the rest of humanity. On a boat. With a bunch of animals.

It all sounds familiar; doesn’t it? Over the next few months, we’ll trace through the Epic of Gilgamesh and see what threads we can find there that connect us to such disparate works as Star Trek and the Book of Daniel.

Lesson Number One: Wheaton’s Law really is the oldest one on the books.

I enjoyed the incorporation of Gilgamesh and Enkidu into the Morris’ ‘Hell’ series.

I read Robert Silverberg’s Gilgamesh book some thirty years ago. The tale certainly is epic.

I remember the Silverberg! It was marketed and read as fantasy, even though its really myth.

Going through the Middle Eastern section of the British Museum recently, and listening to the Ancient World podcast, I’m eager to see what you find, Elixabeth!

Great post, Elizabeth. And when you say “Gilgamesh was most likely a historical king who ruled over the Sumerian city of Uruk in the 27th century BCE,” to my brain that sounds so much more ancient 2,700 BCE!

However you put it, that’s a long time ago. And I understand that, according to US copyright law, the tale will soon be in the public domain. 🙂

Well, that’s assuming the current copyright extension bill doesn’t pass. In the meantime, I’m going to establish my rights to the estates of Beowulf and Homer and reaching out to some lawyers …

As I go through it, I hope to play up JUST HOW WEIRD The Epic of Gilgamesh is. It’s literature, and it’s human literature, but it’s alien in some really fundamental ways. I read an article once about a doctor with MSF telling a group of Masai tribesmen the story of Hamlet. It just did not translate. All the premises of the story were completely out of sync with their frame of reference, so they came to the conclusion that Horatio was an evil magician who was out to kill Hamlet and his family.

It’s a bit like that! Six thousand years is a blip geologically but a massive ocean of time in terms of human culture. But it still hits all these amazing tropes.

I haven’t read the Silverberg: I will have to, though, and do a post on it!

I used to read and repeatedly check out from the school library some telling of that ancient King’s life (a bit sanitized, I later read Silverberg’s telling;-) with neat watercolor images.

[…] Ancient Worlds: Everything You Learned About the Epic of Gilgamesh – and Promptly Forgot […]