My Fantasia Festival, Days 15 Through 19: The Fake and Thermae Romae II

A week ago, on Thursday, July 31, I saw yet another movie at the Fantasia Festival. Then I left town for the weekend to attend to some business of my own. I got back in on Sunday, and went to see another movie Monday evening. By that time, I’d also been able to catch up on a couple of films that I’d missed over the weekend — but I’ll be talking about them later. For the moment, I’ll discuss the films I saw in the Fantasia theatres.

A week ago, on Thursday, July 31, I saw yet another movie at the Fantasia Festival. Then I left town for the weekend to attend to some business of my own. I got back in on Sunday, and went to see another movie Monday evening. By that time, I’d also been able to catch up on a couple of films that I’d missed over the weekend — but I’ll be talking about them later. For the moment, I’ll discuss the films I saw in the Fantasia theatres.

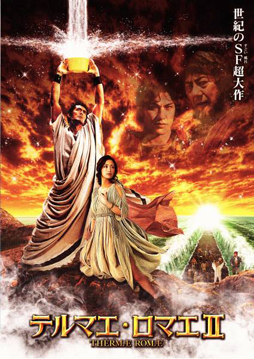

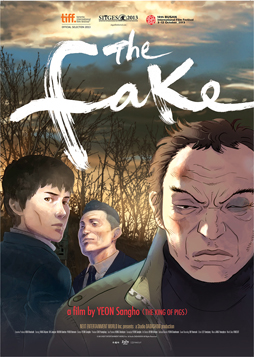

The movie I saw on Thursday was called The Fake (Saibi). It was an animated film from Korea, directed by Yeon Sang-ho from his own script. It’s a harsh, downbeat drama. The movie I saw Monday was almost completely different, a comedy from Japan called Thermae Romae II (Terumae romae II), about a Roman architect who unwittingly travels in time to modern Japan and learns new ways to think about bathhouses. Hideki Takeuchi, who directed the first Thermae Romae, handled direction here as well, though with a change of writers: Hiroshi Hashimoto stepped in for Shogo Muto. Both movies adapt Tokyo-born Chicago resident Mari Yamazaki’s original manga, and as the first screened at last year’s Fantasia festival, I’ll actually talk about both Thermae Romae films in this review.

First, though, I’ll discuss The Fake. It’s set in a small town in Korea about to be flooded by a new dam. A new evangelical pastor has come to town and is raising money for the construction of a new chapel — while also selling a ‘holy water’ that supposedly can work miraculous cures. Min-chul, the town ne’er-do-well, who hits his wife and steals his daughter’s college money, returns to town. After a scrape with Elder Choi, the pastor’s business manager, Min-chul sees a wanted poster and recognises Choi as a con-man. But nobody wants to listen to Min-chul when he tries to tell the truth.

Visually, it’s distinctive. The colour sense is rich and the designs are realistic, but the actual animation — the character movement — seems stilted and jerky. It’s an essentially realistic story, lacking even dream sequences or hallucinations; so you wonder what made animation the right medium for the tale.

Visually, it’s distinctive. The colour sense is rich and the designs are realistic, but the actual animation — the character movement — seems stilted and jerky. It’s an essentially realistic story, lacking even dream sequences or hallucinations; so you wonder what made animation the right medium for the tale.

Like its protagonist, The Fake is not an easy movie to love. It’s bleak, which is fine, but the bleakness feels overdetermined. Violence is abrupt and startling from the first frames of the movie, but often seems to lack either a point or credibility. In an otherwise-realistic movie, characters take deep stab wounds to the chest and then head off on long walks, or take two cracks from a metal pipe directly in the skull and go about their merry way. This is more than just unlikely; when characters suffer no consequences from what ought to be incapacitating damage it starts to call into question what the violence actually means. The realism of the whole thing’s undercut. When a character with no particular fighting background attacks a group of four experienced, prepared, armed men who see him coming, and somehow knocks them all out, you become aware of authorial fiat at work.

In other words, the physical brutality is inconsistent. That’s too bad, because the emotional brutality is fascinating. Characters scream and emote; the secondary roles in particular are given real depth, with sudden twists of dialogue, distinctive facial expressions, and highly individual body language. There’s some very good work in building the personalities of these smaller parts, especially an elderly couple who run a convenience store.

Unfortunately, other characters don’t sustain interest. The pastor, Sung, is fascinating for about the first half of the movie, an idealist with — it becomes clear — secrets in his past. Then the pressures on him mount, and he turns into something far more generic. More crucial, I think, is Min-chul. The central conflict of the movie seems to revolve around Min-chul’s attempt to expose Choi as a fraud. But Min-chul’s not acting out of any idealistic motive. He doesn’t like Choi, who beat him up in a bar’s restroom. So he’s trying to hurt him in response. It’s difficult to be engaged with that, as in a sense there isn’t anything at stake. Generally Min-chul doesn’t develop in any way, and in fact spends the movie really refusing to develop and change, to enagage with the world around him except through physical and emotional violence. That could work dramatically, but here it’s not quite realised; Min-chul remains a one-note character.

Unfortunately, other characters don’t sustain interest. The pastor, Sung, is fascinating for about the first half of the movie, an idealist with — it becomes clear — secrets in his past. Then the pressures on him mount, and he turns into something far more generic. More crucial, I think, is Min-chul. The central conflict of the movie seems to revolve around Min-chul’s attempt to expose Choi as a fraud. But Min-chul’s not acting out of any idealistic motive. He doesn’t like Choi, who beat him up in a bar’s restroom. So he’s trying to hurt him in response. It’s difficult to be engaged with that, as in a sense there isn’t anything at stake. Generally Min-chul doesn’t develop in any way, and in fact spends the movie really refusing to develop and change, to enagage with the world around him except through physical and emotional violence. That could work dramatically, but here it’s not quite realised; Min-chul remains a one-note character.

I’ve seen some reviews of the movie that suggest it means to indict religion as a whole (and especially the evangelical Christian movement popular in Korea). If so, and I say this as someone with no particular brief in favour of religion, then the movie’s a failure. The characters are too weak, too compromised when the story opens. As a critique of religion, it leaves itself open to the response that the events it shows only came about because the specific characters it depicts are flawed in their particular ways. One might respond that everyone’s flawed, of course; but even in the world of the movie, that doesn’t answer the point — some of the supporting characters display a quiet moral centre foreign to the leads. The attempt to indict religion as a system fails. As a result, the film makes itself easy to dismiss.

That’s too bad, because there’s a lot otherwise to like. The character motivations are strong and well-dramatised. The pacing and the development of the story are elegant — though coincidence does seem to play an overlarge role in the plot’s construction. There’s a lot of human truth in The Fake, a lot of well-observed emotion. But for all that it’s ambitious and engaged, I think the weakness in the main characters and conception of the film tend to let it down.

It’s always odd to turn from criticising a self-consciously dramatic piece to a self-aware comedy. But above and beyond questions of craft, there are times when a lightness of touch is both pleasurable in itself and also a better way to get a theme across. I thought the first Thermae Romae was a splendid example of that. If the sequel doesn’t seem to have as much on its mind, it still keeps and expands the tone of the original while being, if anything, funnier.

It’s always odd to turn from criticising a self-consciously dramatic piece to a self-aware comedy. But above and beyond questions of craft, there are times when a lightness of touch is both pleasurable in itself and also a better way to get a theme across. I thought the first Thermae Romae was a splendid example of that. If the sequel doesn’t seem to have as much on its mind, it still keeps and expands the tone of the original while being, if anything, funnier.

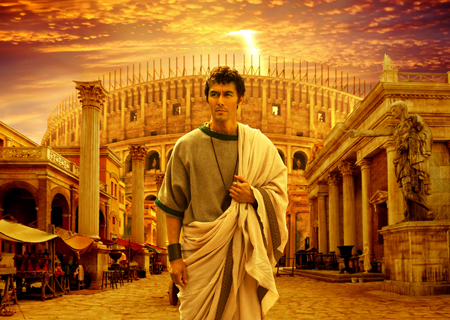

Both movies follow Lucius Modestus (Hiroshi Abe), a designer of bathhouses in Rome in the second century under the Emperor Hadrian (Masachika Ichimura). The first movie begins with Lucius disgusted by contemporary architecture, dreaming of finding a new way to build bathhouses. By means that the movies cheerfully refuse to explain he travels in time to modern Japan, where he’s dumbstruck by the new plumbing technology he sees. Back in Rome, he tries to build what he’s seen with the tools available to him. Complications ensue, as does a love affair with a modern Japanese woman and aspiring mangaka, Mami (Aya Ueto). By the end of the two movies the Roman Empire’s been repeatedly saved by the construction of new bathhouses, the Emperor’s established a new policy of peace, and Mami’s become a bestselling manga star who’s seeing her story about a time-travelling Roman architect being turned into a film. These aren’t spoilers; you know fairly early on what sort of movies you’re watching. The pleasure is in the clever, screwball way in which things unfold. And the many great gags along the way.

I felt the first movie did a little better than the second in getting a theme across under the gags. The first Thermae Romae was a hilarious and upbeat film about cultural appropriation and cultural misunderstandings. When Lucius first finds himself in the lands of the “flat-faced clan” he assumes that this people he’s never seen before are slaves — he, after all, is a Roman, and therefore master of the world. Then he sees their advanced plumbing technology, and is repeatedly humbled to tears. He builds what he sees back in Rome, but is haunted by the notion that he’s only cribbed innovations from another people. How can Rome really hold itself up as the rightful master of the world when another nation is so far ahead of them?

This is a movie from Japan set in the Italian peninsula that uses Madama Butterfly on the soundtrack, so I think it’s safe to say it’s aware of cross-cultural issues (a cute, and particularly surreal running gag is the accompaniment of opera music whenever Lucius time-travels). The use of Japanese actors to play Roman roles, while European actors play minor parts in the Roman scenes, is particularly pointed. That said, I didn’t see anything confrontational in the movie; it always maintains its lightness of touch. There’s something amusing in the way the Japanese characters seem to make allowances for Lucius doing inappropriate or thoughtless things because he’s a foreigner (as opposed to being a time-traveller). The second movie does aim at a more character-oriented theme, as Lucius and Mami in their different ways attempt to develop a new and more original power in their art. I don’t see the obstacles they face as being very tightly linked to this point, but by the end of the movie they reach their aim.

This is a movie from Japan set in the Italian peninsula that uses Madama Butterfly on the soundtrack, so I think it’s safe to say it’s aware of cross-cultural issues (a cute, and particularly surreal running gag is the accompaniment of opera music whenever Lucius time-travels). The use of Japanese actors to play Roman roles, while European actors play minor parts in the Roman scenes, is particularly pointed. That said, I didn’t see anything confrontational in the movie; it always maintains its lightness of touch. There’s something amusing in the way the Japanese characters seem to make allowances for Lucius doing inappropriate or thoughtless things because he’s a foreigner (as opposed to being a time-traveller). The second movie does aim at a more character-oriented theme, as Lucius and Mami in their different ways attempt to develop a new and more original power in their art. I don’t see the obstacles they face as being very tightly linked to this point, but by the end of the movie they reach their aim.

With all this said I want to highlight the most crucial fact about these movies: they’re funny. Very, very funny. They’re clever, conscious of their own ludicrousness, and extract the most comedic momentum possible out of the combination of the two cultures. First you dump a Roman in a bath with a bunch of sumo wrestlers, then you go on with the movie, and then send the wrestlers back in time to Rome. It sounds like a simple idea — mix ancient Rome with modern Japan, repeat as needed — but it works because the movie can spin a single comparison into similarities (gladiatorial combat and sumo wrestling) and major differences (the much much lower fatality rate in sumo wrestling) and minor differences (crowds in the Colosseum throw stones while crowds at a Sumo match throw cushions) and, in the end, show what happens when the Romans try to understand the Japanese (gladiators doing the side-to-side foot-stomp of the sumo). This isn’t to say that the movies avoid simple humour, whether a face-plant into a bowl of noodles or Romans recreating whac-a-mole as whac-a-slave. But often even the broad gags have a certain grasp of culture and how they play out. Pasta being introduced to Rome as Ramen noodles. A character named Ceionius who turns out to have an evil twin named J-onius (so far as I know, a joke that needs the Roman alphabet to work).

Special mention here has to go to Abe. He plays a solemn Roman note-perfectly, and his comedic timing is razor-sharp. So far as I can tell, he handles Latin dialogue excellently, too (the movies use a complex but consistent alternation between Japanese and Latin, until they get bored with it and handwave away the Latin). For all he goes through, Lucius somehow never entirely loses his dignity; his sense of himself as a Roman never cracks, even when he’s staring in awe at a toilet. He’s clearly extremely good at what he does: he’s instantly able to recognise new plumbing fixtures, across a gap of cultures and millennia, and able at once to visualise ways to replicate the experience of the new technology in Rome — mostly through the use of slave labour. Abe builds the man as a character, and particularly as a proud Roman. Dropped in Japan without clothes, he tears down a banner, wraps it around himself, and instinctively patterns it in the shape of a toga.

Special mention here has to go to Abe. He plays a solemn Roman note-perfectly, and his comedic timing is razor-sharp. So far as I can tell, he handles Latin dialogue excellently, too (the movies use a complex but consistent alternation between Japanese and Latin, until they get bored with it and handwave away the Latin). For all he goes through, Lucius somehow never entirely loses his dignity; his sense of himself as a Roman never cracks, even when he’s staring in awe at a toilet. He’s clearly extremely good at what he does: he’s instantly able to recognise new plumbing fixtures, across a gap of cultures and millennia, and able at once to visualise ways to replicate the experience of the new technology in Rome — mostly through the use of slave labour. Abe builds the man as a character, and particularly as a proud Roman. Dropped in Japan without clothes, he tears down a banner, wraps it around himself, and instinctively patterns it in the shape of a toga.

I thought both Thermae Romae movies were hilarious. They’re surprisingly sumptuous productions — Rome is convincingly Roman, and the second movie in particular has several lavish Colosseum scenes. They’re fast-paced and find a good mix of the broad and the clever (and for movies that largely revolve around plumbing, also surprisingly clean). They’re movies about finding connections between cultures, and their own success shows how wonderful that can be.

(You can find links to all my Fantasia diaries here.)

Matthew David Surridge is the author of “The Word of Azrael,” from Black Gate 14. His ongoing web serial is The Fell Gard Codices. You can find him on Facebook, or follow his Twitter account, Fell_Gard.