My Fantasia Festival, Day 11 (part 1): Hal and Giovanni’s Island

There are a couple of things I’ve noticed in my Fantastia experience so far which I haven’t yet mentioned. The first is the general friendliness of people: the ease I’ve had in getting into conversations while in line for a film, or in the theatre waiting for a movie to start. I’ve met other writers, a programming director for a Mexican horror film festival (check it out), and, on the Sunday before last (July 27), a DJ with Concordia University’s radio station, CJLO.

There are a couple of things I’ve noticed in my Fantastia experience so far which I haven’t yet mentioned. The first is the general friendliness of people: the ease I’ve had in getting into conversations while in line for a film, or in the theatre waiting for a movie to start. I’ve met other writers, a programming director for a Mexican horror film festival (check it out), and, on the Sunday before last (July 27), a DJ with Concordia University’s radio station, CJLO.

Fantasia’s hosted on Concordia’s downtown campus, and DJ Saturn de Los Angeles is one of a number of CJLO DJs who play music before the start of films in the Hall Theater, while the audience is filing in and finding their seats. And this is the other element of the festival I’ve not yet written about, the pre-film music. As selected by the DJs up at the back of the Hall to fit with the movie about to play, it sets the tone and prepares you for what you’re about to watch. I’ve found the selections appropriate and inventive, adding a little extra style to the Fantasia experience. The music raises your excitement level just a bit, like hearing the pre-show music at a rock concert. You know something’s coming, and when the music stops, your attention focuses on the screen that much more.

Saturn plays Japanese pop and indie rock in their weekly show, so it’s appropriate I met them before the first of two anime films I’d see on the day. We were waiting for the North American premiere of Hal, a character-oriented science-fiction anime that’d be preceded by a short film called Sonny Boy and Dewdrop Girl. After Hal, which was shown in the mid-sized D.B. Clarke Theater, I’d head upstairs to the Hall to see the Canadian premiere of another anime, Giovanni’s Island. I’d then go on to see two more films that Sunday, both documentaries (and coincidentally met more CJLO folks in line at the later one), but I’ll be discussing those in another post. Here, I want to consider the two animated films.

Or, more precisely, three animated films. Sunny Boy and Dewdrop Girl (Hinata no Aoshigure) is an 18-minute piece about the daydreams of two kids in love. The boy’s a shy artist, while the girl’s more popular; when she moves away and leaves their school, the boy at first can’t bear to say goodbye and then sets off at a run to say some final words to her. Directed and written by Hiroyasu Ishida, the whole thing serves as a framework for some nice daydream images and a final hallucinatory sequence during the boy’s run in which he imagines himself flying on a giant bird over an empty city being reclaimed by nature. The flight sequences aren’t bad, occasionally recalling Miyazaki, but the plot’s slight and there was some sexualization of the kids that, for me, seemed out of place.

Or, more precisely, three animated films. Sunny Boy and Dewdrop Girl (Hinata no Aoshigure) is an 18-minute piece about the daydreams of two kids in love. The boy’s a shy artist, while the girl’s more popular; when she moves away and leaves their school, the boy at first can’t bear to say goodbye and then sets off at a run to say some final words to her. Directed and written by Hiroyasu Ishida, the whole thing serves as a framework for some nice daydream images and a final hallucinatory sequence during the boy’s run in which he imagines himself flying on a giant bird over an empty city being reclaimed by nature. The flight sequences aren’t bad, occasionally recalling Miyazaki, but the plot’s slight and there was some sexualization of the kids that, for me, seemed out of place.

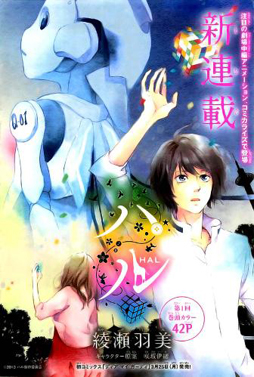

Hal (originally Haru) was a more serious affair. Directed by Ryotaro Makihara from a script by Izumi Kizara, it’s set in the near future when robots are common household servants. We see a plane crash, and find that a man named Hal (voiced by Yoshimasa Hosoya) has been killed. His girlfriend Kurumi (Yoko Hikasa) is in deep mourning, and her grandfather upgrades a robot to look like Hal in order to bring her out of it. Twists in the plot soon emerge: it’s not clear Hal was a very nice person. Sub-plots emerge around the folk in a seniors’ residence and a former colleague of Hal’s named Ryu. At the end, the film turns itself neatly on its head, and we end up re-evaluating everything we thought we’d been watching.

It’s a short movie, only about sixty minutes, and well done. The art is relatively realistic, and the animation’s fluid. There’s a careful attention to the details of daily life, to showing people doing the laundry and preparing food, which helps further ground it in reality. In fact, the movie does something I can’t remember seeing anywhere else, in any medium: it depicts a world that seems much like our own with some upgrades in things like robots and smart video cameras, then at one point gives us a flashback to Hal’s former life that’s filled with more science-fictional imagery — men in stylised hazmat suits and what looks like a cyberpunk junkpile. So the effect is to create a present-day world which flashes back to a science-fiction scene.

It’s a short movie, only about sixty minutes, and well done. The art is relatively realistic, and the animation’s fluid. There’s a careful attention to the details of daily life, to showing people doing the laundry and preparing food, which helps further ground it in reality. In fact, the movie does something I can’t remember seeing anywhere else, in any medium: it depicts a world that seems much like our own with some upgrades in things like robots and smart video cameras, then at one point gives us a flashback to Hal’s former life that’s filled with more science-fictional imagery — men in stylised hazmat suits and what looks like a cyberpunk junkpile. So the effect is to create a present-day world which flashes back to a science-fiction scene.

Which isn’t to say that the worldbuilding’s inconsistent. In fact, the film’s depiction of economics and of consumerism is particularly effective. A major theme in the film seems to be the balance between the traditional life and the need for money; the way modern society demands generating money to live, as opposed to, for example, artisanal craft. It’s a nicely-handled stress in the original Hal’s relationship, and it pops up in inventive ways in his new life, as Hal 2.0 tries to understand the concept of value and its difference from monetary worth.

Also at work in the movie is a consideration of remembrance; of memory and of tradition. Hence the seniors’ residence; this is, overall, a story about making peace with the dead. The movie begins with characters hand-washing and hand-drying fabric, and if it seems to show a world much like our own, it’s also showing a kind of timelessness — one of the nice ideas in the film is the way the lovers used to communicate with each other by Rubik’s Cube, writing down wishes and desires on a solid-coloured face before scrambling the cube into randomness. I think it’s a little more complicated than showing a degenerate modernity versus traditional values, though; I think the movie at least tries to balance the two things, showing respect to the past while describing the difficult choices to be made in the present. It’s a well-made film.

Also at work in the movie is a consideration of remembrance; of memory and of tradition. Hence the seniors’ residence; this is, overall, a story about making peace with the dead. The movie begins with characters hand-washing and hand-drying fabric, and if it seems to show a world much like our own, it’s also showing a kind of timelessness — one of the nice ideas in the film is the way the lovers used to communicate with each other by Rubik’s Cube, writing down wishes and desires on a solid-coloured face before scrambling the cube into randomness. I think it’s a little more complicated than showing a degenerate modernity versus traditional values, though; I think the movie at least tries to balance the two things, showing respect to the past while describing the difficult choices to be made in the present. It’s a well-made film.

Giovanni’s Island (Giovanni no Shima) may be a great film. The story’s framed by an elderly man and woman returning to an island after years away, and most of the movie’s flashback, the man remembering why they had to leave. It was the end of the Second World War, and the island of Shikotan, Japanese territory north of Japan proper, was occupied by Soviet troops. The film nicely builds the life of the fisherfolk who live on the island, then shows the dislocation that follows the arrival of the Soviets, and the way the Japanese and Russians come to live together — before further changes arrive.

It lives in its characters: Junpei (Kota Yokoyama), the old man in the framing sequence, and his brother, Kanta (Junya Taniai). Their teacher, Sawako (Yukie Nakama), in love with their father, Tatsuo (Masachika Ichimura), the man left in charge of the Japanese community when the Soviets remove the island’s defense force. Also Hideo (Yusuke Santamaria), their uncle, a smuggler and “indestructible wandering crow.” And the Russians as well, notably Tanya (Polina Ilyushenko), the daughter of the Soviet commander, with whom Junpei strikes up a touching friendship.

The film’s sensitively directed by Mizuho Nishikubo from a powerful script by Shigemichi Sugita and Yoshiki Sakurai based on a story by Sugita. Designs are stylised and incredibly effective. Cartoony drawings are given substance by textured colour; everything has a kind of grain that gives it detail and a distinctive three-dimensionality. Characters move fluidly, with their own body language. Occasional dream sequences and visions have a neon-bright colour that stands out in contrast.

The film’s sensitively directed by Mizuho Nishikubo from a powerful script by Shigemichi Sugita and Yoshiki Sakurai based on a story by Sugita. Designs are stylised and incredibly effective. Cartoony drawings are given substance by textured colour; everything has a kind of grain that gives it detail and a distinctive three-dimensionality. Characters move fluidly, with their own body language. Occasional dream sequences and visions have a neon-bright colour that stands out in contrast.

Most of those visions have to do with Night on the Galactic Railroad (here Galactic Railroad, originally Ginga Tetsudo no Yoru), a novel by Kenji Miyazawa written around 1927 and published posthumously in 1934. The story clearly informs the movie, but not knowing the novel, I can’t really speak to that. A look at a plot description does suggest a number of thematic resonances, particularly in dealing with death. Certainly images of trains, and of journeys by train, become a repeated and powerful motif. I found that the film worked admirably well even without knowledge of Galactic Railroad; it tells you all that you need to know. For example: Junpei and Kanta are Japanese versions of the names of the main characters, Giovanni and Campanella. So Junpei is the Giovanni of the film’s title.

The plot of the movie is obvious, but honest. It’s a character-driven piece whose characters are to some extent caught up in history. Junpei develops naturally through the film, as things go from bad to worse and he and his family must survive events. The writing’s stunningly strong, evoking and developing character through both major events and small, touching exchanges. It’s a tearjerker, perhaps, but the emotional affect is very real. It has to do with community, with unity; like Hal, it’s about memory and the departed. It’s about home, and reaching home, and what home is.

There’s a moment in the film, after the Russians have arrived on the island and taken over the schoolroom where the Japanese children used to learn, where the two groups of children in neighbouring rooms are both singing different national songs. At first they compete, trying to sing over each other. Then they switch, the Japanese children singing in Russian and the Russians in Japanese. It’s an elegant visual and aural sign of the children reaching out to each other while not actually being in the same room. It recalls similar musical moments in Casablanca and La Grande Illusion, but rather than enforce the division between nations as in those films, it serves to unify both. It’s an example of the film’s ability to handle emotionally powerful material in a broad yet very true way.

There’s a moment in the film, after the Russians have arrived on the island and taken over the schoolroom where the Japanese children used to learn, where the two groups of children in neighbouring rooms are both singing different national songs. At first they compete, trying to sing over each other. Then they switch, the Japanese children singing in Russian and the Russians in Japanese. It’s an elegant visual and aural sign of the children reaching out to each other while not actually being in the same room. It recalls similar musical moments in Casablanca and La Grande Illusion, but rather than enforce the division between nations as in those films, it serves to unify both. It’s an example of the film’s ability to handle emotionally powerful material in a broad yet very true way.

The different cultures and the way they interact are well-drawn (besides the Japanese and Russian characters, there’s a minor role for a Korean which illustrates another side to things). The languages used in a given situation by a given character, alternately Japanese and Russian, are consistently well-chosen and help to illustrate who they are. The ways the characters orbit around each other, coming toward each other and drawing back, are nicely imagined; plot emerges from character, particularly in the latter half of the film as seeds planted early on grow and flower. The conclusion is touching, a sweet resolution that also acknowledges what has been lost, in one way or another.

Giovanni’s Island is a deeply realistic, deeply humanistic movie. The craft is stunning, but it’s a film that aims at whatever you want to call the realm of excellence that lies beyond craft; and it reaches that aim. It’s powerful, involving, and ultimately both melancholic and uplifting. I think it’s one of the best movies I’ve seen at the Fantasia Festival so far.

(You can find links to all my Fantasia diaries here.)

Matthew David Surridge is the author of “The Word of Azrael,” from Black Gate 14. His ongoing web serial is The Fell Gard Codices. You can find him on Facebook, or follow his Twitter account, Fell_Gard.