My Fantasia Festival, Day 9: The Infinite Man and Closer to God

In a surprising number of ways the experience of having a pass for a movie festival is not wholly unlike the experience of going to a science-fiction convention. One such similarity is the inevitability of conflicts in your ideal schedule. You’ll see two potentially interesting things on at once. So you pick and choose and guess which of the things looks like it’ll be better.

In a surprising number of ways the experience of having a pass for a movie festival is not wholly unlike the experience of going to a science-fiction convention. One such similarity is the inevitability of conflicts in your ideal schedule. You’ll see two potentially interesting things on at once. So you pick and choose and guess which of the things looks like it’ll be better.

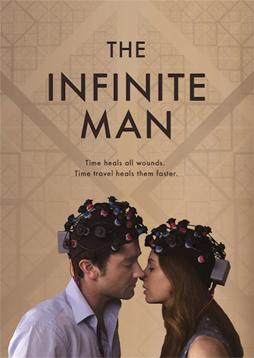

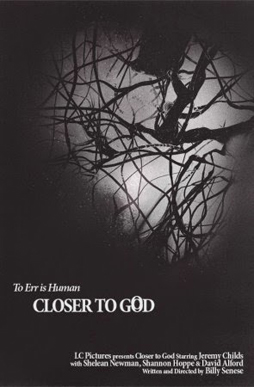

At 5 PM on Friday, July 25, a Korean film called Mr. Go screened in the Hall Theater, a 3D comedy about an ape that played professional baseball. It sounded like it might be funny (I mean, you know, apes!), but I decided I’d much rather see The Infinite Man at 5:20, an Australian comedy about a man who invents time travel in a desperate attempt to repair his relationship with the woman he loves. After that, a movie called Yasmine, about a young woman studying martial arts, played at 7:50; it’s the first commercial film from the Sultanate of Brunei, but while I thought it’d be interesting to see a country’s first movie, I decided I didn’t want to take the chance of missing a science-fiction film about cloning called Closer to God, which screened at 9:35. I’m still not sure how those choices worked out.

The Infinite Man was directed and written by Hugh Sullivan. It stars Josh McConville as Dean, a somewhat uptight scientist madly in love with Lana, played by Hannah Marshall. They’ve been together at least a couple of years, but their relationship’s in trouble due to Dean’s obsessive need to control things around him. It probably doesn’t help that Lana is being stalked by Terry (Alex Dimitriades, who plays the part with a note-perfect blend of menace and goofiness), an Olympic-level javelin thrower who dated her briefly four years ago. At any rate, Dean decides to rekindle his romance by going back to the resort where he spent a perfect day with Lana the year before. But the resort’s gone out of business. And then Terry shows up. And Lana leaves with him. So Dean does the only logical thing: moves into the resort and builds a time machine so he can go back and set things right. Events don’t go quite according to plan. He has to go back again, and runs into himself, and Lana ends up going back as well, and then so does Terry, and complications feed on complications.

The comedy’s perfectly timed (as it were), and consistently underplayed. McConville centres the film, playing the same role in multiple iterations and making things read cleanly. Marshall is effective as the somewhat underwritten love interest, but Dimitriades steals the show as the absurd Terry. Visually, the film stays in the same location for almost its entire duration, and it more-or-less works. But that conceit has problems of its own.

The comedy’s perfectly timed (as it were), and consistently underplayed. McConville centres the film, playing the same role in multiple iterations and making things read cleanly. Marshall is effective as the somewhat underwritten love interest, but Dimitriades steals the show as the absurd Terry. Visually, the film stays in the same location for almost its entire duration, and it more-or-less works. But that conceit has problems of its own.

The time machine in this movie is very limited. It takes people back exactly one year, after which they (typically) physically live through the next year before going back and trying to change the original scenario. That’s fair enough. But some of those characters live at the same abandoned resort during the year, and at a certain point it becomes clear that we’re supposed to accept that they’re not all aware of each others’ existence.

More than that: this is a story in which the rules of time travel (it seems) prohibit changing the past. Terry, who imagines himself as being of Greek descent, has some lines about Greek tragedy that reinforce the point. But for that to work, the story has to ensure that characters are always motivated to take the actions that fate dictates they’re going to take. I’m not at all convinced that that happens here. Specifically, I felt that given the amount of time some of the characters spend with other iterations of other characters, it would be reasonable to expect them to sit down and talk through who they were and what was happening. Which would have stopped the story, if it had happened.

More than that, some of the character choices are baffling. Dean is jealous of himself in other iterations. That does point up his possessiveness and need to control everything, but it’s hard to swallow that somebody who understands time well enough to invent a time machine would actually feel that way.

More than that, some of the character choices are baffling. Dean is jealous of himself in other iterations. That does point up his possessiveness and need to control everything, but it’s hard to swallow that somebody who understands time well enough to invent a time machine would actually feel that way.

After several seasons of Steven Moffat’s Doctor Who, complex time travel stories are beginning to become familiar in mass media. Still, The Infinite Man is less like Who — the plotting’s tighter, and the tone is much more grounded — and more like the movie Primer played as comedy. It has a thoughtful ending, which helps, but I wasn’t entirely convinced.

Closer to God was a different story. Written and directed by Billy Senese, it follows scientist Victor Reed (Jeremy Childs), who as the movie begins announces that he’s successfully cloned a human being, a baby he’s named Elizabeth. At first, the movie looks like it’ll follow the social ramifications of the announcement, and examine the nature of doing controversial science: conversations in boardrooms about how to handle announcements and legal liability, the reaction of the media, the onset of protesters. Then it switches track, and we get a family drama based around Victor, his wife, and an older couple who live on their estate and take care of a child named Ethan (Isaac Disney) who has some sort of handicap or medical condition (what that is becomes clear as the film goes on, as does Ethan’s relationship to Victor). Then it switches track again, and the mostly-unseen Ethan becomes a sinister figure as a horror-movie feel emerges.

Closer to God was a different story. Written and directed by Billy Senese, it follows scientist Victor Reed (Jeremy Childs), who as the movie begins announces that he’s successfully cloned a human being, a baby he’s named Elizabeth. At first, the movie looks like it’ll follow the social ramifications of the announcement, and examine the nature of doing controversial science: conversations in boardrooms about how to handle announcements and legal liability, the reaction of the media, the onset of protesters. Then it switches track, and we get a family drama based around Victor, his wife, and an older couple who live on their estate and take care of a child named Ethan (Isaac Disney) who has some sort of handicap or medical condition (what that is becomes clear as the film goes on, as does Ethan’s relationship to Victor). Then it switches track again, and the mostly-unseen Ethan becomes a sinister figure as a horror-movie feel emerges.

I’d like to be able to say it all works. So much about the movie is well done. The lighting and direction are beautiful and effective, producing a series of startling and expressive images. The soundtrack and general sound design are excellent. The acting’s generally solid and Childs in particular is excellent.

But the writing doesn’t seem to come together. The different plot strands seem to sit beside each other without being mutually supporting. The movie’s final shift into horror-film territory gives it a certain energy, but much of what came before seems needless. Some of the decisions made by Victor Reed seem unmotivated, notably taking his clone into his home instead of hiring more security for her at the hospital where she’s being kept. Other decisions, notably the origin of Ethan, end up seeming excessively convenient in terms of plot and theme (the occasional absence of cell phones, particularly at the climax, is also convenient). Victor’s backers, seen in the first scene of the movie, never return and the source of his financing and institutional support remains unclear. And the protesters who appear seemed to me alternately facile and baffling.

But the writing doesn’t seem to come together. The different plot strands seem to sit beside each other without being mutually supporting. The movie’s final shift into horror-film territory gives it a certain energy, but much of what came before seems needless. Some of the decisions made by Victor Reed seem unmotivated, notably taking his clone into his home instead of hiring more security for her at the hospital where she’s being kept. Other decisions, notably the origin of Ethan, end up seeming excessively convenient in terms of plot and theme (the occasional absence of cell phones, particularly at the climax, is also convenient). Victor’s backers, seen in the first scene of the movie, never return and the source of his financing and institutional support remains unclear. And the protesters who appear seemed to me alternately facile and baffling.

In some ways I wonder if this is the first obvious case at this festival of my missing something crucial due to a cultural difference. The filmmakers are, almost entirely, from Nashville. At a question-and-answer session, they talked about how easy it was to find people in Tennessee wiling to protest cloning, and about wanting to show “both sides” of the controversy. I have to admit, as a Montrealer with no particular religious background, I don’t really see what the controversy is — I understand that one wants to ensure that human cloning is studied with all appropriate controls, but I found the protesters screaming about clones lacking souls to be deeply alien.

The question-and-answer, with Senese, Childs, Disney, and composer Thomas Nola, was fascinating (as usual, what follows comes from notes I hand-wrote during the event). It started with an interview in which Senese spoke about the research he put into the topic of cloning, and his deep interest in Frankenstein, both the original novel and the movie version. Childs discussed sharing a vision with Senese, and how they both appreciated grounded movies, citing films from the 1970s such as Serpico. Senese wrote extensive backgrounds for all the characters, helping them prepare for their roles even when the background didn’t appear onscreen; Childs mentioned, for example, that according to the background he was given Victor named the clone ‘Elizabeth’ (the name of Victor Frankenstein’s adopted sister and wife) after a sister of his who died as an infant. Senese discussed the long journey of working with the rough cut of the film, and re-arranging the various pieces of the movie to make it all work.

Questions came from the audience, some of them I thought quite pointed and well-chosen. Asked about his inspirations, Senese cited Frankenstein again and the science of cloning, and his desire to tell a Frankenstein-like story around cloning. Asked what he thought the protesters he’d shown would have done with the baby if they’d been given it, Senese said he wasn’t sure. Asked whether Ethan had been consciously intended to evoke an autistic child, and how he expected that would play to people familiar with autism, Senese said that he’d intended to depict a child in pain due to excessive growth, with the unceasing pain causing an equally-unceasing rage.

Questions came from the audience, some of them I thought quite pointed and well-chosen. Asked about his inspirations, Senese cited Frankenstein again and the science of cloning, and his desire to tell a Frankenstein-like story around cloning. Asked what he thought the protesters he’d shown would have done with the baby if they’d been given it, Senese said he wasn’t sure. Asked whether Ethan had been consciously intended to evoke an autistic child, and how he expected that would play to people familiar with autism, Senese said that he’d intended to depict a child in pain due to excessive growth, with the unceasing pain causing an equally-unceasing rage.

Senese was then given a question about the process of making the movie, and how long it took, Senese said that it took some time as the makers all had other jobs. So it took nine months to write, followed by three or four months of pre-production, three months of shooting, and a year of post-production — all funded out-of-pocket. There are no active plans at the moment for a general release, but he is working with sales people, and believes something is cooking. Finally, asked about the use of genre in the movie as a way to explore social issues, Senese said that he’s less interested in social commentary and more in trying to blend genres together and make it work. But, of course, studios are afraid of movies like that, which try something different.

I hate to sound like a movie studio, but I don’t think this experiment in blending genres worked. It’s too bad, because many of the individual ingredients of the movie are quite good and Senese clearly has a very strong sense of shot construction and an eye for images. But the movie seemed to bite off more than it could chew. It occasionally tried to discuss issues of media depiction, of social reaction to new science, and of how science is done; but these things seemed to go nowhere, as did the scenes dealing with its main character’s home life. Closer to God is Senese’s first feature, and in many ways it seems to me to be like the archetypal difficult first novel by a knockout stylist who doesn’t have full command of story structure and an overambitious idea of what fits in the story and what doesn’t. There’s potential and talent here, but the story just doesn’t cohere. It’s cinematically interesting, but narratively dysfunctional. It’s strong enough that I’ll keep an eye out for what Senese does next, but in and of itself I can’t recommend it.

I hate to sound like a movie studio, but I don’t think this experiment in blending genres worked. It’s too bad, because many of the individual ingredients of the movie are quite good and Senese clearly has a very strong sense of shot construction and an eye for images. But the movie seemed to bite off more than it could chew. It occasionally tried to discuss issues of media depiction, of social reaction to new science, and of how science is done; but these things seemed to go nowhere, as did the scenes dealing with its main character’s home life. Closer to God is Senese’s first feature, and in many ways it seems to me to be like the archetypal difficult first novel by a knockout stylist who doesn’t have full command of story structure and an overambitious idea of what fits in the story and what doesn’t. There’s potential and talent here, but the story just doesn’t cohere. It’s cinematically interesting, but narratively dysfunctional. It’s strong enough that I’ll keep an eye out for what Senese does next, but in and of itself I can’t recommend it.

(You can find links to all my Fantasia diaries here.)

Matthew David Surridge is the author of “The Word of Azrael,” from Black Gate 14. His ongoing web serial is The Fell Gard Codices. You can find him on Facebook, or follow his Twitter account, Fell_Gard.