My Fantasia Festival, Day Four: Jellyfish Eyes, In the Land of the Head Hunters, and The Reconstruction of William Zero

Last Sunday, June 20, I saw four movies. I’ve already written about one of them, Terry Gilliam’s The Zero Theorem, which deserved its own post. But that’s not to say that all the other films I saw that day were poor. It was in fact an odd mix; out of the three other films I saw, I’m quite glad to have seen two of them, while the third at least had points of interest.

Last Sunday, June 20, I saw four movies. I’ve already written about one of them, Terry Gilliam’s The Zero Theorem, which deserved its own post. But that’s not to say that all the other films I saw that day were poor. It was in fact an odd mix; out of the three other films I saw, I’m quite glad to have seen two of them, while the third at least had points of interest.

Things began with Takashi Murakami’s children’s fantasy Jellyfish Eyes (Mememe no Kuragi in the original Japanese), which was followed by The Zero Theorem, both at the Hall Theatre. Then I went across the street to the De Sève to watch an utterly fascinating silent film from 1914, Edward Curtis’s In the Land of the Head Hunters, which mixed an early attempt at anthropological documentary into a fantasy adventure. My day concluded with Dan Bush’s intelligent low-budget sf film The Reconstruction of William Zero. Put them all together, and it made for a memorable cinematic experience.

That said, Jellyfish Eyes was something of a disappointment. Murakami’s an internationally-renowned artist, known in particular for creating or identifying the ‘superflat’ style of art — the word’s meant to refer not only to Murakami’s own style, but to the Japanese artistic tradition in general. Which emphatically includes popular art. Anime and manga artists have been exhibited in ‘superflat’ gallery shows, and Murakami’s own art has been said to be inspired by anime. The impression I get from what I’ve read is that it’s almost a take on the idea of pop art, combining Japanese popular culture with certain aspects of graphic design as a way of critiquing consumerism. So, all in all, it’s perhaps not entirely surprising that Murakami’s first film was an anime-inflected mash-up of Pokémon, kaiju, even a bit of Spielberg; nor surprising that its potential is largely nullified by a bluntness of approach.

Young Masashi (Takuto Sueoka) and his widowed mother move to a new town following the death of Masashi’s father, but Masashi finds a strange creature at his new home, a floating bloblike thing he names ‘Kurage-Bo,’ or ‘Jellyfish Boy.’ Then he finds out that every kid at his new school has one of these creatures — and some of the students have started fighting rings with their ‘pets.’ But we in the audience have learned that the creatures, the Friends, are the product of strange research into children’s negative emotional energy; four black-cloaked villains have conscripted Masashi’s uncle, a researcher at the local lab that created these creatures, into their evil plans. They’re planning to use the negative energy generated by the fights to summon yet more power, and create yet more disaster.

Young Masashi (Takuto Sueoka) and his widowed mother move to a new town following the death of Masashi’s father, but Masashi finds a strange creature at his new home, a floating bloblike thing he names ‘Kurage-Bo,’ or ‘Jellyfish Boy.’ Then he finds out that every kid at his new school has one of these creatures — and some of the students have started fighting rings with their ‘pets.’ But we in the audience have learned that the creatures, the Friends, are the product of strange research into children’s negative emotional energy; four black-cloaked villains have conscripted Masashi’s uncle, a researcher at the local lab that created these creatures, into their evil plans. They’re planning to use the negative energy generated by the fights to summon yet more power, and create yet more disaster.

Murakami directed from his own story, with the script written by Yoshihiro Nishimura and Jun Tsugita. It’s oddly simple; so much so I wondered if it was meant to be some sort of ironic pose — which at least might explain the overdone acting. And the obvious parallels with Pokémon or (in the way Masashi first meets Kurage-Bo and lures him with snack food) E.T. But I couldn’t see a way where that sort of reading helped the film. It’s a strange thing; dark themes like the Fukushima disaster and school bullying seem to jut out uncomfortably from the armature of a good-versus-evil kids’ movie with a quartet of cackling bad guys. Emotional development of the characters is undercut by melodrama, and the plot grows more haphazard as it goes on: you start to wonder how the Friends work, and why one character has multiple Friends when no-one else does, and why one Friend is significantly larger than the others, and how all these kids have managed to hide the existence of the Friends from all the adults for a year, and before long it all falls apart.

Characters have changes of heart that seem unmotivated or too convenient. Friends develop new powers at will. The female lead, Saki (Himeka Asami) is weirdly sidelined during the climax: she urges Masashi, at this point without his own Friend, to go on to where everything’s happening while she and her strong oversized Friend will remain behind to “take care of things” — it’s not clear what things need to be taken care of, but it does mean she’s in position to be (rather incredibly) caught up by the movie’s last and gravest threat, thus giving Masashi and Kurage-Bo someone to rescue.

Characters have changes of heart that seem unmotivated or too convenient. Friends develop new powers at will. The female lead, Saki (Himeka Asami) is weirdly sidelined during the climax: she urges Masashi, at this point without his own Friend, to go on to where everything’s happening while she and her strong oversized Friend will remain behind to “take care of things” — it’s not clear what things need to be taken care of, but it does mean she’s in position to be (rather incredibly) caught up by the movie’s last and gravest threat, thus giving Masashi and Kurage-Bo someone to rescue.

The Friends were strong visual designs — all by Murakami, including some creations of his from earlier artwork — but I can’t honestly say I found them significantly more visually interesting than Pokémon designs. There was a deliberate cartooniness to the CGI that was interesting. But I didn’t feel it was enough to make the movie stand out, though it has to be said the audience in the Hall Theatre seemed on the whole entertained. Still, for me this one ranks as one of the disappointments of the festival so far.

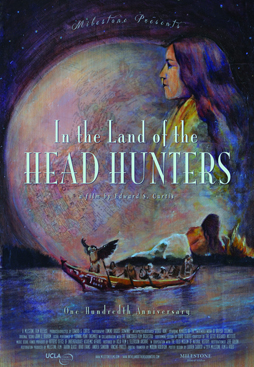

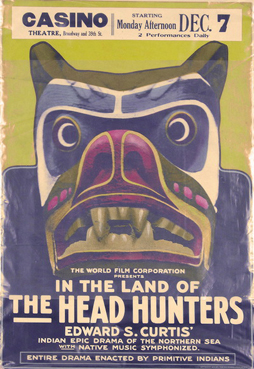

After Jellyfish Eyes I stayed in the Hall for The Zero Theorem, then headed across the street to the relatively small De Sève Theatre for the showing of In the Land of the Head Hunters. A hundred-year old film set among one of the First Nations of the west coast of British Columbia, it was preceded by a presentation by filmmaker Manon Barbeau and André Dudemaine. Dudemaine’s the artistic director for the company behind Présence Autochtone, the Montréal First Peoples Festival, while Barbeau is the founder of Wapikoni Mobile, an institution that sends travelling film studios to First Nations communities, encouraging the development of Aboriginal filmmakers and the preservation of Aboriginal culture in general. Barbeau and Dudemaine spoke a bit about In the Land of the Head Hunters, then introduced a short film that had emerged through the Wapikoni Mobile project: Réal junior Leblanc’s Tremblement de Terre (Nanameshkueu), an experimental piece featuring Leblanc reading a poem he wrote over split-screen images.

After Jellyfish Eyes I stayed in the Hall for The Zero Theorem, then headed across the street to the relatively small De Sève Theatre for the showing of In the Land of the Head Hunters. A hundred-year old film set among one of the First Nations of the west coast of British Columbia, it was preceded by a presentation by filmmaker Manon Barbeau and André Dudemaine. Dudemaine’s the artistic director for the company behind Présence Autochtone, the Montréal First Peoples Festival, while Barbeau is the founder of Wapikoni Mobile, an institution that sends travelling film studios to First Nations communities, encouraging the development of Aboriginal filmmakers and the preservation of Aboriginal culture in general. Barbeau and Dudemaine spoke a bit about In the Land of the Head Hunters, then introduced a short film that had emerged through the Wapikoni Mobile project: Réal junior Leblanc’s Tremblement de Terre (Nanameshkueu), an experimental piece featuring Leblanc reading a poem he wrote over split-screen images.

After the short, Head Hunters began. Directed and written by Edward Curtis, it’s a mix of anthropology and adventure story. Curtis is famous for his photographing and documentation of indigenous North American peoples, recording their language, music, history and culture. Head Hunters was an attempt to extend this project to the new medium of the feature film, while at the same time making money to continue his other projects. It focusses on the Kwakwaka’wakw, telling the story of a chief’s son who falls in love with a woman coveted by an evil sorcerer. The sorceror’s brother is another chief, and so the love brings about war.

At the time the film was made, the word ‘documentary’ had not been coined; the movie is therefore an artifact from a time before genres had stratified, before even the strict distinction (in film, at least) between fiction and non-fiction. Head Hunters is a dramatic story with spaces for recording cultural elements of anthropological interest: a wedding ceremony, costumed dancers, hunting expeditions, battles. But one must be wary. Curtis was not above staging his photographs, and sometimes getting things wrong as a result; and so it is here. Many of the magical elements are archaic. Other things, from hairstyles to hunting scenes, are inauthentic.

At the time the film was made, the word ‘documentary’ had not been coined; the movie is therefore an artifact from a time before genres had stratified, before even the strict distinction (in film, at least) between fiction and non-fiction. Head Hunters is a dramatic story with spaces for recording cultural elements of anthropological interest: a wedding ceremony, costumed dancers, hunting expeditions, battles. But one must be wary. Curtis was not above staging his photographs, and sometimes getting things wrong as a result; and so it is here. Many of the magical elements are archaic. Other things, from hairstyles to hunting scenes, are inauthentic.

It seems to me that this still leaves much that is of value: the architecture alone is interesting. At any rate I can say that as a film, Head Hunters works. There’s a beauty to many of its images (sea lions dropping from a rocky island like a living avalanche; a striking double-exposure special effect in a vision). The story’s surprisingly effective given that the movie was trying to document elements of culture as well as present a narrative. What happens, I feel, is that the more documentary material helps to build a world and thus indirectly establish character. You come to understand the sense of the magical world in which the characters move, to understand something of what is important to them. At the same time the core scenario of the film is highly dramatic without being overwrought; there’s an elemental directness to it that works well in a silent film. It’s mythic. And, in the end, also intriguing, surprising, and involving.

After the film, Dudemaine discussed some of the issues surrounding its making, including Curtis’ deviations from authenticity. He also talked a bit about the restored print that we saw. Though critics raved about it on its release, the movie never became a popular success and only two incomplete prints have survived. The restoration’s been put together out of the usable elements of both, but some scenes are still missing; this version of the film, soon to be released on DVD to mark the film’s hundredth anniversary, uses stills where original shots are unavailable. Barbeau then discussed the Wapikoni Mobile project, and the development of First Peoples’ cinema.

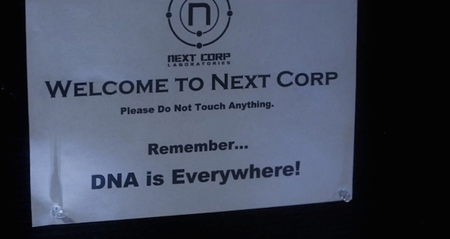

After which, I crossed the street to the D.B. Clarke theatre, and took in the world premiere of The Reconstruction of William Zero, presented by director Dan Bush, who co-wrote the movie with star Conal Byrne. Byrne plays multiple roles in the film, as a research scientist and as the man claiming to be his twin brother. A few years before the beginning of the story, this scientist, William Blakely, accidentally killed his son. That set off a chain of events which unfold throughout the movie, involving Blakely’s research, his estranged wife, and an escalating amount of violence.

After which, I crossed the street to the D.B. Clarke theatre, and took in the world premiere of The Reconstruction of William Zero, presented by director Dan Bush, who co-wrote the movie with star Conal Byrne. Byrne plays multiple roles in the film, as a research scientist and as the man claiming to be his twin brother. A few years before the beginning of the story, this scientist, William Blakely, accidentally killed his son. That set off a chain of events which unfold throughout the movie, involving Blakely’s research, his estranged wife, and an escalating amount of violence.

I’m being intentionally vague because the movie involves at least two major plot twists. One is obvious. The other isn’t. Much of the effect of the film comes from discovering them or having them confirmed. And a large part of what makes the movie work is that the twists feel natural; not only are they logical and unforced, they immediately bring characters into clearer focus. The film plays fair.

It is fairly slow, concentrating on mood, especially early on. This is a good choice, developing emotional texture while almost unobtrusively introducing scientific concepts and backstory that’ll prove to be important. The lighting, pacing, and sound create an introspective, quiet atmosphere, even an elegaic feeling — while at the same time creating a sense of things slightly out of whack that builds nicely as the movie goes on. Byrne’s work is key to all this. He’s hardly ever off the screen, and he carries the movie, creating clear distinctions between characters who have the same face. Especially during the moody early parts of the film you’re interested in what all his characters do; in what they’re thinking, and why.

It is fairly slow, concentrating on mood, especially early on. This is a good choice, developing emotional texture while almost unobtrusively introducing scientific concepts and backstory that’ll prove to be important. The lighting, pacing, and sound create an introspective, quiet atmosphere, even an elegaic feeling — while at the same time creating a sense of things slightly out of whack that builds nicely as the movie goes on. Byrne’s work is key to all this. He’s hardly ever off the screen, and he carries the movie, creating clear distinctions between characters who have the same face. Especially during the moody early parts of the film you’re interested in what all his characters do; in what they’re thinking, and why.

Conversely, there’s an extended section toward the end of the movie where things seem too conventional — all the mysteries have been resolved, and there’s a standard stop-the-bad-guy-and-save-the-girl sequence. And that’s set up by a long expository monologue a villain gives (once he’s been revealed as a villain). It’s not entirely unmotivated — you can see the character talking things out as a way of explaining himself to himself, and being somewhat surprised at what he finds — but it feels overly convenient. Convenient, as well, is another character’s sudden return at the very end.

But the movie easily overcomes these things. It’s a tremendously effective piece of science-fiction filmmaking. That is, it’s not just an effective story, but an effective story defined by its science-fictional concept; a story where the concept is perfectly fused with character. It’s in the humanist vein of a Theodore Sturgeon, or maybe the Robert Silverberg of Dying Inside. It really is about the reconstruction of a man, told in an unorthodox way that could only work as science fiction. While the carefully-built atmosphere can drag a little in the early going, the sturdy craft ultimately pays off. This is a movie that becomes stronger as you think about it afterward; as you fit all the themes and character aspects into place, and the tightness and overall coherency of the picture become more and more clear.

But the movie easily overcomes these things. It’s a tremendously effective piece of science-fiction filmmaking. That is, it’s not just an effective story, but an effective story defined by its science-fictional concept; a story where the concept is perfectly fused with character. It’s in the humanist vein of a Theodore Sturgeon, or maybe the Robert Silverberg of Dying Inside. It really is about the reconstruction of a man, told in an unorthodox way that could only work as science fiction. While the carefully-built atmosphere can drag a little in the early going, the sturdy craft ultimately pays off. This is a movie that becomes stronger as you think about it afterward; as you fit all the themes and character aspects into place, and the tightness and overall coherency of the picture become more and more clear.

Bush came out after the film for a discussion with the audience. Asked about Byrne’s acting in the film, he said that he and Byrne had worked together for years and had developed a kind of shorthand between them. Keeping the characters Byrne played distinct and clear was a constant concern. Byrne developed a different physicality for the different characters, building his performance out of that. Bush said that Byrne was ultimately able to go from one character to another as though he were flipping a switch. Bush spoke as well about the personal influences on his own work in the film, on experiencing loss, and on how many of his films have to do with finding a place.

He observed that movies like Primer and Another Earth seemed to be grappling with the same science-fictional approach that he was; and indeed that he himself was working on another movie with a similar theme. Asked about why he’d made a science fiction movie, Bush said that to him “the future’s already here,” citing advances in genetics and nanotechnology. “I’m drawn to it as an entry point to character,” he said, noting that the material fascinated him but needed to serve character: “I’m not as interested in the mechanics of the stuff as I am in getting you guys to believe” in what’s on screen.

He observed that movies like Primer and Another Earth seemed to be grappling with the same science-fictional approach that he was; and indeed that he himself was working on another movie with a similar theme. Asked about why he’d made a science fiction movie, Bush said that to him “the future’s already here,” citing advances in genetics and nanotechnology. “I’m drawn to it as an entry point to character,” he said, noting that the material fascinated him but needed to serve character: “I’m not as interested in the mechanics of the stuff as I am in getting you guys to believe” in what’s on screen.

I found Bush’s answer to one of the final questions interesting. Asked whether the name “William Blakely” was a reference to William Blake, he said it was a nod to Blake’s Songs of Innocence and of Experience. That has an obvious relevance to the way the character’s bifurcated on screen, but Blake’s cosmology actually goes farther than the two contrary states of the soul. I don’t know how far Bush meant to take the comparison, but his William Blakely really does go through a reconstruction, and you could argue that he ends up in the “organized innocence” that Blake imagined beyond both innocence and experience.

We see Blakely’s reconstruction in an epilogue that ties together strands and hints from throughout the movie. I thought it was a strong ending to a strong film. The Reconstruction of William Zero is idea-based science fiction, as well a character-centred story in which the main character is never who we think he is. It’s a patient, thoughtful film that rewards patience and thoughtfulness in the audience. For me, it’s one of the great successes of the festival so far.

(You can find links to all my Fantasia diaries here.)

Matthew David Surridge is the author of “The Word of Azrael,” from Black Gate 14. His ongoing web serial is The Fell Gard Codices. You can find him on Facebook, or follow his Twitter account, Fell_Gard.