Fantasia Focus: The Zero Theorem, by Terry Gilliam

Before continuing my Fantasia diary with a look at the movies I saw last Sunday, I want to focus in on one specific film that struck me as an utterly brilliant piece of science-fiction satire. I think it divided the audience; I’ve heard and seen reactions from people who were left cold by it as well as from people who loved it as much as I did. Perhaps that’s not surprising. The movie is The Zero Theorem, directed by Terry Gilliam from a script by Pat Rushin, and it is as idiosyncratic and persistently individual as you’d expect from Gilliam.

Before continuing my Fantasia diary with a look at the movies I saw last Sunday, I want to focus in on one specific film that struck me as an utterly brilliant piece of science-fiction satire. I think it divided the audience; I’ve heard and seen reactions from people who were left cold by it as well as from people who loved it as much as I did. Perhaps that’s not surprising. The movie is The Zero Theorem, directed by Terry Gilliam from a script by Pat Rushin, and it is as idiosyncratic and persistently individual as you’d expect from Gilliam.

Qohen Leth (Christoph Waltz) is an eccentric solitary in a hyperconnected future. He works for a corporation, Mancom, plugging numbers together — which he does by manipulating blocks on a screen with a joystick, effectively playing video games. A chance encounter with Management (Matt Damon) allows him to work from home, a deserted church, trying to put together the zero theorem, a mathematical proof of the pointlessness of life — which Management believes can be leveraged to make money. Qohen’s pleased, since what he wants more than anything else in life is a phone call he believes will come out of the blue and grant him enlightenment, and now he can sit at home and wait for the phone to ring. But his solitude’s plagued by outsiders, including the seductive Bainsley (Mélanie Thierry), and Management’s son Bob (Lucas Hedges), an even sharper computer whiz than Qohen.

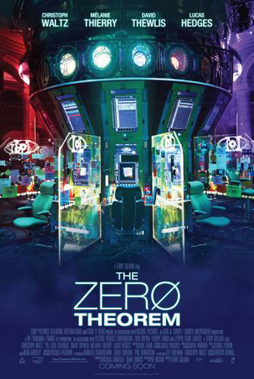

The Zero Theorem is visually startling, steampunk gone day-glo. It’s a perceptive, idiosyncratic take on the Wired World Of Today, here depicted as Brave New World gone berserk. In fact, Gilliam considers this movie part of his ‘Orwellian trilogy,’ along with Brazil and Twelve Monkeys, but it certainly feels more like Huxley. It depicts a world commercialised and infantilised, where ads for the Church of Batman the Redeemer float above the street. It’s a sharp criticism of easy escapism, but seems to question as well where contrasting meaning is to be found, whether religious transcendence is valid or whether belief is just another form of escape. The movie’s more interested in questions than answers, even questioning itself and its own metaphors on occasion. Days later, I’m still thinking about it, arguing with it, astounded by it.

Let’s start with the design of Gilliam’s future. It’s a triumph in beautiful tastelessness. An advertising slogan tells us that “Enough is never enough!” and that’s the motto of the world he’s built. It’s frighteningly probable; a bit where Qohen seems to be followed by an especially persistent ad as he walks along the street recalls one of the sanctioned-by-futurists ideas in Spielberg’s Minority Report — as well as speculations about the near-term functionality of Google Glass and augmented reality. But Gilliam’s clearly disgusted by the trivia of constantly-running news tickers saying nothing important, by ads that demand attention, by corporations patronising people, by citizens becoming redefined as consumers. Everything is less than it appears, banality that’s funny to see on screen but terrifying to think about as an actual future.

Let’s start with the design of Gilliam’s future. It’s a triumph in beautiful tastelessness. An advertising slogan tells us that “Enough is never enough!” and that’s the motto of the world he’s built. It’s frighteningly probable; a bit where Qohen seems to be followed by an especially persistent ad as he walks along the street recalls one of the sanctioned-by-futurists ideas in Spielberg’s Minority Report — as well as speculations about the near-term functionality of Google Glass and augmented reality. But Gilliam’s clearly disgusted by the trivia of constantly-running news tickers saying nothing important, by ads that demand attention, by corporations patronising people, by citizens becoming redefined as consumers. Everything is less than it appears, banality that’s funny to see on screen but terrifying to think about as an actual future.

Gilliam’s built a world dense with references and visual noise, with things to look at. You can see the influence from the Harvey Kurtzman/Will Elder collaborations in the old Mad Magazine, where every square millimetre of panel space was filled with gags. The bitterness of Gilliam’s satire recalls the wiseassedness of Mad, but cuts deeper. So he shows us glimpses of capitalism appropriating counter-cultural activism: “Occupy Wall Street today!” burbles one ad, while another comes to us by way of “Corporations Sans Frontières.” It’s an incredible torrent of bright absurd imagery that highlights both the hedonism and meaninglessness of the future, a world where everybody’s exploiter and exploited, where emotional experience exists to be packaged, where everything real has become a simulacrum of itself to be sold.

Implicitly, almost unwillingly, Qohen stands in contrast. He’s an agoraphobe, perhaps on the autism spectrum, who can’t deal with this high-volume world. He lives in a deconsecrated church, meaning that Gilliam’s able to contrast the outer world with religious imagery — but how seriously are we to take it? Qohen sets up the computer trying to prove the meaninglessness of life in the chancel, if not actually on the altar, of the old church. He’s oddly intense, whether waiting for his phone call or trying to prove the zero theorem; he’s a broken bald recluse from the outer world obsessed with his own religious beliefs, but he’s not Kurtz and this isn’t Apocalypse Now. Given the atmosphere of his home and his habit of referring to himself in the plural he occasionally recalls the demon Legion cast out by Christ. But in fact I think he’s meant to recall a more prominent Biblical figure.

Implicitly, almost unwillingly, Qohen stands in contrast. He’s an agoraphobe, perhaps on the autism spectrum, who can’t deal with this high-volume world. He lives in a deconsecrated church, meaning that Gilliam’s able to contrast the outer world with religious imagery — but how seriously are we to take it? Qohen sets up the computer trying to prove the meaninglessness of life in the chancel, if not actually on the altar, of the old church. He’s oddly intense, whether waiting for his phone call or trying to prove the zero theorem; he’s a broken bald recluse from the outer world obsessed with his own religious beliefs, but he’s not Kurtz and this isn’t Apocalypse Now. Given the atmosphere of his home and his habit of referring to himself in the plural he occasionally recalls the demon Legion cast out by Christ. But in fact I think he’s meant to recall a more prominent Biblical figure.

Qohen’s given a calling by Management, and goes out into the wilderness (of his own quiet home). There the son of Man(agement) comes to him, and proves to be better at his assigned task. There’s a seductive woman (Bainsley) who seems to contribute to his eventual downfall. And at a key point Qohen saves the life of Management’s son by immersing him in cold water. This all seems to be giving us Qohen as a parallel to John the Baptist. If so, it’s a take unlike most others: the Baptist here is a marginal figure, an aging recluse desperately hoping for a call, an enlightenment, that may never come. He’s outliving his usefulness, entering obsolescence, being overtaken by the newer younger model. (Conversely, one wonders if the Biblical Baptist is something here of a model for Gilliam himself, “one crying in the wilderness,” an old satirist seeing the coming world creating new vistas of banality.)

But at the same time Gilliam undercuts the parallel relentlessly, not least by having Management explicitly state that he’s not God or the Devil. Management’s son Bob also mocks the idea of ‘chosen ones’ and saviours, which is, all things considered, tremendously ironic. Still, the fact is that Biblical echoes abound. Pat Rushin, the scriptwriter, has spoken of being inspired to write the movie by the book of Ecclesiastes (in Hebrew Koheleth, thus the name of the main character). Qohen’s put-upon boss (David Thewlis) is named Joby. And, of course, Qohen’s home is filled with religious sculpture and art.

But at the same time Gilliam undercuts the parallel relentlessly, not least by having Management explicitly state that he’s not God or the Devil. Management’s son Bob also mocks the idea of ‘chosen ones’ and saviours, which is, all things considered, tremendously ironic. Still, the fact is that Biblical echoes abound. Pat Rushin, the scriptwriter, has spoken of being inspired to write the movie by the book of Ecclesiastes (in Hebrew Koheleth, thus the name of the main character). Qohen’s put-upon boss (David Thewlis) is named Joby. And, of course, Qohen’s home is filled with religious sculpture and art.

Baptist or not, what does it all add up to? Qohen seems to end the film in control of his private world, but Gilliam has stated that the film’s a tragedy. I think that The Zero Theorem, in its ending and in much else, bears the same relation to Brazil that Huxley does to Orwell. So Qohen’s got the opportunity to make something meaningful, but has been shaped by the society around him in such a way that he’s incapable of exercising his imagination in a meaningful way. His choice to live his life waiting for a phone call to give him meaning results in a life without any meaning. All is vanity, as Ecclesiastes might say.

But the film seems to go further, to demand deeper and tougher questions. Is there a significant distinction to be made between a religion based on Christ on the one hand and the church of Batman the Redeemer on the other? If so, is the difference in the story or in the meaning the believer invests in the story? Is any belief in an eternal afterlife only a distraction from this life? What is escapism, and if it is bad, why? What is imagination, and if it is good, why? What is meaning, and where is it to be located?

But the film seems to go further, to demand deeper and tougher questions. Is there a significant distinction to be made between a religion based on Christ on the one hand and the church of Batman the Redeemer on the other? If so, is the difference in the story or in the meaning the believer invests in the story? Is any belief in an eternal afterlife only a distraction from this life? What is escapism, and if it is bad, why? What is imagination, and if it is good, why? What is meaning, and where is it to be located?

It’s not copping out for Gilliam to refuse to answer these questions. He raises them slyly, I think, as it were edgewise. But to me they’re questions that come to seem more and more important to the film the more you think about it. As I said, The Zero Theorem is science-fictional satire of the highest order; it’s Gilliam in top form. I think it’s bound to be divisive just because it is so incisive. Parts of it may be obvious, but parts of it are difficult to assimilate. It’s a great, troubling, rich, generous, acidic, overwhelming film, and one that demands to be thought over and debated for a long time to come.

(You can find links to all my Fantasia diaries here.)

Matthew David Surridge is the author of “The Word of Azrael,” from Black Gate 14. His ongoing web serial is The Fell Gard Codices. You can find him on Facebook, or follow his Twitter account, Fell_Gard.

Surridge (on behalf of said film): “Is there a significant distinction to be made between a religion based on Christ on the one hand and the church of Batman the Redeemer on the other?”

From someone on the outside looking in (like Gilliam), I suppose the answer is “no”.

From a (traditional) religious person, I’m sure the answer is “Yes, my religion is based upon truth, those other religions are either completely false or have some mixture of falsehood.”

Matthew,

Wow! This sounds fantastic.

James: Yeah, that’s the thing, isn’t it? How much does the answer change according to your position? I think there’s a complicating factor, in that Gilliam’s an artist, and seems from all I can tell to believe in the power of art. So what’s the difference then between artistic power and religious power? Is there a difference in the way it’s used, or in what it inspires people to go do?

This is what I mean about the film … the more I think about it, the more questions I have.

John: For me, probably the film of the festival so far.

You had me at, “directed by Terry Gilliam”. I’ve liked just about everything I’ve ever seen of his. Yes, even Tideland. Well, that one less so than most.

I’ve been wondering where Gilliam’s been hiding. Now I know! Thanks for the post.