My Fantasia Festival, Day Three (Part Two): Han Gong-ju and Thou Wast Mild and Lovely

To my mind, if you’re a critic of any integrity, sooner or later the criticism you write will lead you to challenge your views of yourself as well as your views of the art you experience. That’s the nature of much truly effective art: it makes you look at yourself and think about yourself in new ways. If you’re trying to articulate your reaction and assessment of such a work, honesty will compel some self-examination as well. Powerful art requires an acknowledgement of one’s subjective response.

To my mind, if you’re a critic of any integrity, sooner or later the criticism you write will lead you to challenge your views of yourself as well as your views of the art you experience. That’s the nature of much truly effective art: it makes you look at yourself and think about yourself in new ways. If you’re trying to articulate your reaction and assessment of such a work, honesty will compel some self-examination as well. Powerful art requires an acknowledgement of one’s subjective response.

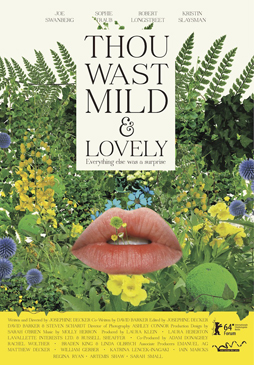

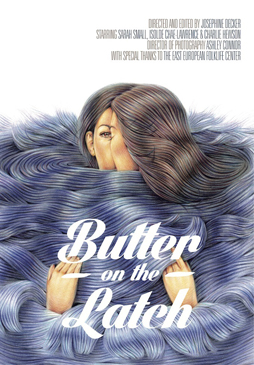

I mention this because the films I saw at the Fantasia festival last Saturday evening both did this in different and complementary ways, leading me to similar conclusions. The first was a South Korean movie called Han Gong-ju, written and directed by Lee Su-Jin. The second was Thou Wast Mild and Lovely, directed by Josephine Decker from a script she co-wrote with David Barker; Decker’s earlier short feature Butter on the Latch screened afterwards.

The eponymous lead of Han Gong-ju is a Korean schoolgirl who, as the movie opens, is being transferred from her old high school to another school in a different city. Why? We don’t know; but it’s clear that something grave has happened. The mother of one of her teachers takes Gong-ju in, and the movie alternates between showing Gong-ju’s new life and flashing back to slowly answer the question of what caused this sudden and massive change.

It’s an extremely well-made and powerful movie. The direction is assured, precise, catching exactly the right emotions of exactly the right characters at exactly the right moments. The structure of the script is coolly intelligent, matching the precision of the direction. Dialogue is subtle, and irony used deftly with devastating effect. The acting’s excellent, especially from Chun Woo-hee as Gong-ju. The emotional impact of the film cannot be overstated. This is in all respects a tremendous movie that in every way hits every mark it aims for. It’s already won a slew of prizes at international festivals, and been praised by no less a figure than Martin Scorsese. (The quote: “Han Gong-ju is outstanding in mise-en-scène, image, sound, editing and performance. I have a lot to learn from this movie and I can’t wait to see Lee Su-jin’s next film.” When Martin Scorsese says he has a lot to learn from a movie, that should indicate the level of filmmaking involved.)

So I find myself troubled by my reaction to a movie that I think can be objectively described as a masterpiece. I found after it was done that I had to try to convince myself that I loved the film. Normally one shouldn’t have to try; but I’m fairly sure in this case the problem isn’t with the movie, but with me. Of course it has to be said that the subject matter of the film is emotionally harrowing; it’s a measure of the film’s skill that the central incident that triggers the story is depicted both ruthlessly and yet sensitively. But I don’t think the film’s depiction of evil and of tragedy is what alienates me. I think it’s simply that the film commits itself wholeheartedly, and successfully, to a mimetic aesthetic of a sort that I rarely find involving.

So I find myself troubled by my reaction to a movie that I think can be objectively described as a masterpiece. I found after it was done that I had to try to convince myself that I loved the film. Normally one shouldn’t have to try; but I’m fairly sure in this case the problem isn’t with the movie, but with me. Of course it has to be said that the subject matter of the film is emotionally harrowing; it’s a measure of the film’s skill that the central incident that triggers the story is depicted both ruthlessly and yet sensitively. But I don’t think the film’s depiction of evil and of tragedy is what alienates me. I think it’s simply that the film commits itself wholeheartedly, and successfully, to a mimetic aesthetic of a sort that I rarely find involving.

There’s absolutely no fantasy element to the movie, nor is there any kind of genre sensibility here at all. It is true that there’s some mystery at the start about what happened to start events in motion; but we very quickly realise what kind of movie we’re watching, what type of story we’re in. This is not a ghost story, or a crime story, much less science fiction. This is realism, which works according to realist and mimetic conventions. And it’s a specific kind of realism that consciously shuns the surreal.

It’s a beautifully shot movie, with memorable images that hide their own artifice. It is in fact beautiful precisely because Lee and cinematographer Hong Jae-sik have an eye for the real beauty of real life. It’s a film that’s wise about violence and especially about power; about how power works, and how it relates to gender, and brings these themes out through closely-observed realistic character interactions.

It’s a beautifully shot movie, with memorable images that hide their own artifice. It is in fact beautiful precisely because Lee and cinematographer Hong Jae-sik have an eye for the real beauty of real life. It’s a film that’s wise about violence and especially about power; about how power works, and how it relates to gender, and brings these themes out through closely-observed realistic character interactions.

And I what I learned about myself is that for me all this is not enough. I find Han Gong-ju an admirable movie, but I can’t bring myself to feel deeply about it. There’s something lacking; not in the film, but in me. It’s so tightly constructed, so precise, I feel as though I have no room to empathise with it imaginatively. I’m not saying any kind of non-mimetic element would have made it better. But for me the most memorable image in the film comes from a subplot, when Gong-ju unexpectedly comes across an elderly couple gravely dancing in a closed convenience store. There’s a lovely just-so unexpectedness to the image, capturing in the real a moment beyond the real. And I wish there had been more like that, while acknowledging that it’s no flaw in the movie that there is not.

Thou Wast Mild and Lovely is filled with exactly the sort of moments I’m trying to describe. It’s not a fantasy, or not really, though there are some dream sequences that seem to blur chronology. Presented by director and co-writer Josephine Decker, it was followed by a question-and-answer period with Decker and then by Butter on the Latch. The movies together had exactly the dimension I felt myself missing in Han Gong-ju; seemed, in fact, to live entirely within that dimension.

Thou Wast Mild and Lovely is filled with exactly the sort of moments I’m trying to describe. It’s not a fantasy, or not really, though there are some dream sequences that seem to blur chronology. Presented by director and co-writer Josephine Decker, it was followed by a question-and-answer period with Decker and then by Butter on the Latch. The movies together had exactly the dimension I felt myself missing in Han Gong-ju; seemed, in fact, to live entirely within that dimension.

Thou Wast Mild and Lovely — the title comes from a hymn mourning a young woman’s death and looking ahead to a reunion with her in heaven — gives us a small farming family, old Jeremiah and young Sarah (Robert Longstreet and Sophie Traub), who hire a worker for the summer, Akin (Joe Swanberg). A physical attraction begins to develop between Sarah and the married Akin. Jeremiah’s not pleased, and events snowball, eventually involving Akin’s wife Drew (Kristin Slaysman) and family.

It sounds simple, but it isn’t; there are a number of arresting moments and lines that seem to change or challenge what we think is going on, symbolically and even on a plot level. It’s a movie that does things in non-standard ways. The scenes accrete in a fashion that isn’t typical film narrative. There’s extensive use of out-of-focus photography and tight, unusual framing. Dialogue carries a different kind of weight than in most dramatic speech; the movie, in fact, made me aware of the extent that film is still conceived and made through the lens of drama.

I felt as well that this was a very Lynchian movie. The influence isn’t excessive by any means, but points of similarity are there: a bright and detailed soundtrack, dreams depicted in ominous flashes, an attitude to violence that is unblinking and yet somehow whimsical without being at all ironic. Mostly, though, Mild and Lovely (and Butter on the Latch as well) reminded me of Lynch in their sense of excited experimentalism. These are movies that are always trying something different, and usually getting a payoff out of it.

I felt as well that this was a very Lynchian movie. The influence isn’t excessive by any means, but points of similarity are there: a bright and detailed soundtrack, dreams depicted in ominous flashes, an attitude to violence that is unblinking and yet somehow whimsical without being at all ironic. Mostly, though, Mild and Lovely (and Butter on the Latch as well) reminded me of Lynch in their sense of excited experimentalism. These are movies that are always trying something different, and usually getting a payoff out of it.

The moments these movies present are not necessarily standard cinematic moments. And they’re all the more powerful as a result. I felt that the deep focus photography of the natural settings — the movie was shot in Kentucky — was often startling not only in its beauty but in its rightness, in the way it caught some kind of emotional undercurrent. Mist rising from a river hidden behind a screen of trees. A rainbow against a grey sky (the female lead also in frame, seen from behind as by the watching Akin).

The depiction of nature, and of life on the farm, doesn’t shy away from the muck as well as the beauty. Sex and blood seemed linked. In fact, unlike most films concerned with the erotic, Mild and Lovely allows sexuality to be slightly pathetic, even squalid. Voyeurism and masturbation have about as much screen time as infidelity, and seem at least as important in shaping character. Similarly, horror iconography appears, but in unusual ways, almost normalised: blood’s a part of life, especially if you live on a farm.

In the question-and-answer period, Decker described her influences as primarily literary, especially Steinbeck (with East of Eden a particular influence on Mild and Lovely) and magic realism. That comes through, I think, in the way the film uses dialogue in a more novelistic manner than most movies. I think also that even without the sort of explicitly fantastic moments of magical realism, there is an openness to dreams, a toying with the idea of witchcraft, that inflects the movie with a distinct atmosphere.

In the question-and-answer period, Decker described her influences as primarily literary, especially Steinbeck (with East of Eden a particular influence on Mild and Lovely) and magic realism. That comes through, I think, in the way the film uses dialogue in a more novelistic manner than most movies. I think also that even without the sort of explicitly fantastic moments of magical realism, there is an openness to dreams, a toying with the idea of witchcraft, that inflects the movie with a distinct atmosphere.

Character and plot emerge indirectly. Decker said that she was “just trying to make a really normal movie,” but that it got stranger as the process went on, and observed that “in books much less has to happen to be exciting” because undercurrents have a certain weight that doesn’t come across in much drama or film — as she said, the tension of the present becomes fused with the past or future in different ways. Of course film depicts characters’ inner worlds, but the process of doing so is different as the medium is different.

Thou Wast Mild and Lovely is a film that demands to be re-watched to be wholly understood, as does the largely-improvised Butter on the Latch (which mostly follows two women at an artists’ retreat, following their friendship and the romantic couplings they become involved in; though to say that is to elide many of the complications of the film). These movies have been hailed by The New Yorker, I think accurately, as developing a new kind of narrative grammar. Both have a primal oneiric sense that I find utterly compelling. These are movies that demand a certain alertness from the audience, but that reward the alertness with powerful experiences.

Thou Wast Mild and Lovely is a film that demands to be re-watched to be wholly understood, as does the largely-improvised Butter on the Latch (which mostly follows two women at an artists’ retreat, following their friendship and the romantic couplings they become involved in; though to say that is to elide many of the complications of the film). These movies have been hailed by The New Yorker, I think accurately, as developing a new kind of narrative grammar. Both have a primal oneiric sense that I find utterly compelling. These are movies that demand a certain alertness from the audience, but that reward the alertness with powerful experiences.

What I learned last Saturday about myself as a viewer is that the reward I personally get from something experimental and open to the magical is greater than the reward I get from a perfect work of mimetic craft. And so I learned something else: that the power I find in fantasy is not necessarily directly linked to the openly fantastic, but to a kind of attitude to the world that is fundamentally magical. This is perhaps not surprising. But it’s a pleasure to come across two works of art that together make the point so clearly.

(You can find links to all my Fantasia diaries here.)

Matthew David Surridge is the author of “The Word of Azrael,” from Black Gate 14. His ongoing web serial is The Fell Gard Codices. You can find him on Facebook, or follow his Twitter account, Fell_Gard.