My Fantasia Festival, Day 2: Kite and Open Windows

On Friday night, the cats came out at Fantasia.

On Friday night, the cats came out at Fantasia.

They may have been around on Thursday, too, but this was the first I’d heard them this year. It’s one of the traditions that’ve sprung up at Fantasia: some years ago a series of short films called Simon’s Cat fostered an outbreak of meows among the audience (or, for the francophones, miaous). Somehow it spread to the rest of the festival. And then returned the next year. So, now, when the lights go down for a film — but before anything starts playing on the screen — you’ll hear the audience calling out meows. And the occasional ‘woof’ or ‘baa,’ just for variety.

Friday night, I saw two films welcomed by meows. Kite, a bloody near-future sf film, played at 6:35 in the big Hall Theatre, preceded by a short comedy, Raging Balls of Steel Justice. Then I headed downstairs to the D.B. Clarke Theatre to catch a twisty thriller called Open Windows. I don’t think either feature was entirely successful, but both qualified as ‘interesting,’ the latter rather more than the former.

Let’s begin with the short. Steel Justice is a violent, raunchy parody of 80s action movies, done in claymation. A Sledge Hammer!-style supercop and his horny robot sidekick have to save a prominent banker who’s been kidnapped by a barn full of escaped convicts. Much carnage ensues. It’s quick, fluidly animated, and extremely gross. As the saying goes: people who like this sort of thing will find this the sort of thing they like. The humour wasn’t quite to my taste, and it did feel quite a lot like the aforementioned Sledge Hammer! without network content guidelines. For some, that’ll be enough to make it different; as it happens, not for me. At any rate, what it does, it does competently.

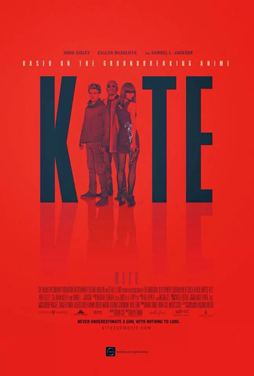

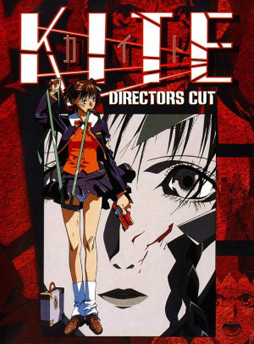

Kite, directed by Ralph Ziman and written by Brian Cox, is a remake of Yasuomi Umetsu’s 1998 anime of the same name. It takes place after a societal collapse caused by a global financial crisis. Government and law enforcement are losing their grip. Gangs and human traffickers thrive amid crumbling urban infrastructure. Sawa (India Eisley) is a teen girl whose parents were killed by criminals years ago; her father was a cop, and his old partner — Karl, played by Samuel L. Jackson — helps her take vengeance on the underworld. Posing as a prostitute she infiltrates the gangs, aiming at the mysterious figure called the Emir, who murdered her parents. But Sawa’s getting sloppy. She’s become addicted to a drug called amp that represses memories and emotions. And a mysterious figure from her past has begun to appear, a boy her age named Oburi (Callan McAuliffe). Mysteries and twists unfold as the film moves on its bloody way.

Kite, directed by Ralph Ziman and written by Brian Cox, is a remake of Yasuomi Umetsu’s 1998 anime of the same name. It takes place after a societal collapse caused by a global financial crisis. Government and law enforcement are losing their grip. Gangs and human traffickers thrive amid crumbling urban infrastructure. Sawa (India Eisley) is a teen girl whose parents were killed by criminals years ago; her father was a cop, and his old partner — Karl, played by Samuel L. Jackson — helps her take vengeance on the underworld. Posing as a prostitute she infiltrates the gangs, aiming at the mysterious figure called the Emir, who murdered her parents. But Sawa’s getting sloppy. She’s become addicted to a drug called amp that represses memories and emotions. And a mysterious figure from her past has begun to appear, a boy her age named Oburi (Callan McAuliffe). Mysteries and twists unfold as the film moves on its bloody way.

At one point in the film a character asks “Why have a conversation when you can stab someone?” The line’s meant to be sarcastic, but actually sums up Kite’s aesthetic. Only it doesn’t commit to that exploitation attitude nearly enough. The idea of Sawa posing as a prostitute only to turn the tables on the pimps sounds good, but is weirdly underplayed. There’s a memorable scene where Sawa jams a dildo into a bad guy’s mouth, then hits a button on the base of it — at which point we find out it’s actually a hidden gun, and the man’s brains are splattered across the wall behind him. It’s a good quick beat, and if there’d been more material like that, Kite might have been an interesting movie. It almost certainly wouldn’t have been a good movie, but it at least would have been a good bad movie, instead of what it is — a middling-to-decent bad movie. (Please understand that in most cases I wouldn’t say that more exploding dildos would make for a better story. But with this movie, that’s what we’re left with.)

It’s striking enough to look at, with a muted colour palette for its backgrounds against which Sawa’s wigs and clothes pop. Jump cuts, sometimes excessive, help propel the pace of the movie. There’s a bit of visual symbolism that provides the title of the film, but is underdeveloped until the last shot, when it becomes too blatant. Dialogue tends to rely heavily on cliché. The post-collapse world barely registers as a setting, essentially serving as an excuse to present an urban hellhole dominated by thugs. The acting, while not actually poor, feels routine. Eisley has to play a character whose emotions have been chemically numbed, but the result’s uninvolving. McAuliffe’s simply an enigma for most of the movie. And the always-watchable Jackson is never really more here than just watchable; he does his job, but doesn’t bring much to the film. Only Zane Meas, as the Emir, has any notable charisma, and he’s largely playing an archetype.

It’s striking enough to look at, with a muted colour palette for its backgrounds against which Sawa’s wigs and clothes pop. Jump cuts, sometimes excessive, help propel the pace of the movie. There’s a bit of visual symbolism that provides the title of the film, but is underdeveloped until the last shot, when it becomes too blatant. Dialogue tends to rely heavily on cliché. The post-collapse world barely registers as a setting, essentially serving as an excuse to present an urban hellhole dominated by thugs. The acting, while not actually poor, feels routine. Eisley has to play a character whose emotions have been chemically numbed, but the result’s uninvolving. McAuliffe’s simply an enigma for most of the movie. And the always-watchable Jackson is never really more here than just watchable; he does his job, but doesn’t bring much to the film. Only Zane Meas, as the Emir, has any notable charisma, and he’s largely playing an archetype.

The action scenes are well-choreographed and well-shot, and Sawa’s fighting style seems designed for her as a physically smaller person to battle larger foes. Her skill level does seem to vary wildly from opponent to opponent, though, as the plot demands. That plot in turn is overall fairly simple, with a twist visible from a distance. That twist involves Sawa’s memories being repressed by amp, but that playing-about with memory feels like a missed opportunity — because it’s not used in any other way, the one twist it does set up is obvious. That seems to me to be the problem with Kite as a whole: interesting ideas left underplayed. Sawa’s a character in the vein of Batman — an orphan whose parents were murdered, and who grows up to take violent revenge on criminals while dressed in funny clothes. But her story never ties together fight scenes and sporadic clever ideas into an involving whole.

Open Windows, directed and written by Nacho Vigalondo, is a different kettle of fish. It aims higher, and achieves more. It’s not without some serious problems. But it’s significantly more interesting, and much more likely to repay watching.

The story starts with Nick Chambers, who runs a web site dedicated to actress Jill Goddard. Nick’s won a contest to have dinner with Goddard, who herself is presently doing a round of promotion for her nearest movie — while also dealing with allegations that an unauthorized sex video of her is circulating on the internet. But something goes wrong for Nick, who’s watching Jill’s press conference on his laptop. He gets a call from a man named Chord, who tells him that the dinner’s been cancelled. Nick’s devastated. Chord feels sorry for him, and promises to help — by hacking into Jill’s cell phone, and helping Nick conduct a covert surveillance of Jill as the evening goes on. But this is only the start of a bigger, deeper game. Things go wrong, and get violent, and we’re soon involved in a self-consciously Hitchcockian thriller.

The story starts with Nick Chambers, who runs a web site dedicated to actress Jill Goddard. Nick’s won a contest to have dinner with Goddard, who herself is presently doing a round of promotion for her nearest movie — while also dealing with allegations that an unauthorized sex video of her is circulating on the internet. But something goes wrong for Nick, who’s watching Jill’s press conference on his laptop. He gets a call from a man named Chord, who tells him that the dinner’s been cancelled. Nick’s devastated. Chord feels sorry for him, and promises to help — by hacking into Jill’s cell phone, and helping Nick conduct a covert surveillance of Jill as the evening goes on. But this is only the start of a bigger, deeper game. Things go wrong, and get violent, and we’re soon involved in a self-consciously Hitchcockian thriller.

If the title of Open Windows is a clear nod to Rear Window, sharing themes of voyeurism and surveillance, the movie also (as the Fantasia program points out) recalls the technical gimmickry of Rope: not only is the film effectively in real time straight through, it also takes place entirely on Nick’s laptop computer screen, zooming in and out and panning around as video calls come in and new windows open. Theoretically, it’s all one shot, though the pans are frequently fast enough that they function as cuts. It’s a novel idea, though it forces the plot into some strange convolutions, and I’m not sure it really holds up all the way through — notably, the final shots are hard to parse logically.

Still, there are ideas here, about surveillance and technology and celebrity and what we put of ourselves online; and while it severely strains credibility from time to time, there’s enough emotional coherence in the acting that things mostly stay on the rails for at least as long as you’re watching it. Arguably the casting plays to these themes, challenging the audience to move past what we think we might know about the people we see on the screen. Nick is played by Elijah Wood, and while for most of the movie he’s playing a naïve sympathetic protagonist caught up by larger forces, he still crafts a character that feels highly distinct from his Frodo. Jill is played by Sasha Grey, who I thought delivered a fine performance; what I did not know, until I researched the movie afterward, was that she’s a former porn actress. Which seemed to add a level of resonance to the movie’s discussion of celebrity and the internet — to the dynamic of the man running a site dedicated to candid pictures of a woman, and the woman herself, trying to make a career in a field where obsessive fans come with the territory, and trying to move past the sexual fantasies others project upon her.

Still, there are ideas here, about surveillance and technology and celebrity and what we put of ourselves online; and while it severely strains credibility from time to time, there’s enough emotional coherence in the acting that things mostly stay on the rails for at least as long as you’re watching it. Arguably the casting plays to these themes, challenging the audience to move past what we think we might know about the people we see on the screen. Nick is played by Elijah Wood, and while for most of the movie he’s playing a naïve sympathetic protagonist caught up by larger forces, he still crafts a character that feels highly distinct from his Frodo. Jill is played by Sasha Grey, who I thought delivered a fine performance; what I did not know, until I researched the movie afterward, was that she’s a former porn actress. Which seemed to add a level of resonance to the movie’s discussion of celebrity and the internet — to the dynamic of the man running a site dedicated to candid pictures of a woman, and the woman herself, trying to make a career in a field where obsessive fans come with the territory, and trying to move past the sexual fantasies others project upon her.

There’s a scene, one of the more harrowing parts of the film, when Chord’s forcing Nick to give Jill increasingly sexualised orders while Nick watches on his laptop. It seems to crystallise many of the movie’s interests, to get at that dynamic of watcher and watched, subject and object — while also depicting the male giving orders as himself struggling against a more powerful and darker personality. It’s an uncomfortable scene to watch, in that you wonder if it’s overly exploitative; and then you wonder if it has to be exploitative to get its point across. Early in the movie, Chord encourages Nick to take revenge on Jill by reassuring Nick that he’s a “nice guy” done wrong by a “stuck-up bitch.” Nick gives in, leading more-or-less directly to the rest of the film, but there’s perhaps a way to read events in which the two men are symbolically different sides of the same personality, Chord as Nick’s id encouraging him to more and more transgressive acts, Nick trying to find a way to contain the damage Chord is doing.

At any rate, the film goes on, accumulating twists and coincidences. Not only do the artifices of the plot become more and more obvious, but the movie’s depiction of technology is increasingly divorced from reality. That’s a problem when it’s trying to say something about the use of that technology. It is true that the film is ultimately less concerned with depicting mundane reality than creating its own amped-up thriller-movie reality, and that’s all to the good. But as the internal continuity becomes more complex, it becomes increasingly distant from the audience. Coincidence takes more of a role in building the plot. Events are revealed to be caused by over-complicated plans. The movie comes to feel increasingly contrived.

At any rate, the film goes on, accumulating twists and coincidences. Not only do the artifices of the plot become more and more obvious, but the movie’s depiction of technology is increasingly divorced from reality. That’s a problem when it’s trying to say something about the use of that technology. It is true that the film is ultimately less concerned with depicting mundane reality than creating its own amped-up thriller-movie reality, and that’s all to the good. But as the internal continuity becomes more complex, it becomes increasingly distant from the audience. Coincidence takes more of a role in building the plot. Events are revealed to be caused by over-complicated plans. The movie comes to feel increasingly contrived.

Essentially, Open Windows ends up as a series of nice set-pieces and ideas within a questionable framework. To me, it works well enough (unlike Kite) because those set-pieces seem to revolve around the same thematic ideas, because the actors do a good job of presenting characters who feel real in wildly unreal situations, and because the real-time conceit builds a propulsive momentum that keeps things moving through impossibilities. The plot does enough of a job that it all holds together, if only just. It’s a still a good movie, but only up to a point; it’s just good enough I wished it were better.

(You can find links to all my Fantasia diaries here.)

Matthew David Surridge is the author of “The Word of Azrael,” from Black Gate 14. His ongoing web serial is The Fell Gard Codices. You can find him on Facebook, or follow his Twitter account, Fell_Gard.