My Fantasia Festival, Day 1: Ghost in the Shell

Last night’s opening film at the seventeenth Fantasia International Film Festival was a 6:30 showing of Jacky au royaume des filles [Jacky in the Kingdom of Women], a French comedy about an oppressive matriarchal country. I decided to give it a pass, opting instead for a 7:45 showing of Mamoru Oshii’s classic anime Ghost in the Shell. Oshii was going to be present, one of two recipients this year of Fantasia’s Lifetime Achievement Award along with Tobe Hooper, whose The Texas Chainsaw Massacre screens on July 30.

Last night’s opening film at the seventeenth Fantasia International Film Festival was a 6:30 showing of Jacky au royaume des filles [Jacky in the Kingdom of Women], a French comedy about an oppressive matriarchal country. I decided to give it a pass, opting instead for a 7:45 showing of Mamoru Oshii’s classic anime Ghost in the Shell. Oshii was going to be present, one of two recipients this year of Fantasia’s Lifetime Achievement Award along with Tobe Hooper, whose The Texas Chainsaw Massacre screens on July 30.

Oshii and Hooper are an odd pairing, but the festival thrives on eclecticism. For 18 years — it skipped a year just after the turn of the century — Fantasia’s been bringing Montrealers the best of genre cinema. This year it’ll be showing more than 160 feature films and 300 shorts over three weeks, including a number of Canadian, North American, and world premieres. I’ll be covering it for Black Gate. I’m planning to post two or three times a week, keeping a running diary of the films I see and adding an occasional longer piece when I see a particularly interesting movie.

Called “The most important and prestigious genre film festival on this continent” by Quentin Tarantino, Fantasia’s become a Montreal institution. I haven’t gone to every installment of the festival, but I was there for the showing of its very first film, My Father Is a Hero, in 1996. It seems to have grown steadily over the years, from wuxia and kaiju and giallo branching out to include films of all sorts from around the world: crime films, horror films, children’s movies, experimental cinema. A look at this year’s selections show the range of offerings, from art-house cinema to a special screening of a Hollywood superhero science-fiction blockbuster. It looks like genre film worldwide is in a healthy state. (Feel free to let me know in comments what films look interesting to you!)

Certainly the festival got off on the right foot, if the crowd for Ghost in the Shell was any indication. The 387-seat D.B. Clarke Theatre was packed, with a few people standing at the back as things got underway. Rupert Bottenberg, Fantasia’s co-programmer of animation, started by welcoming the crowd to the festival, describing the new remastered HD print of Ghost as “direct from the telecine” (Bottenberg, incidentally, is also an artist and graphic novelist, co-creator with Claude Lalumiére of the Lost Myths multimedia fictions). Then he introduced Oshii, describing him as one of the key figures in bringing anime to an international audience by his pioneering of the OVA (or Original Video Animation) form. The crowd rose in a standing ovation as the director took the stage.

Certainly the festival got off on the right foot, if the crowd for Ghost in the Shell was any indication. The 387-seat D.B. Clarke Theatre was packed, with a few people standing at the back as things got underway. Rupert Bottenberg, Fantasia’s co-programmer of animation, started by welcoming the crowd to the festival, describing the new remastered HD print of Ghost as “direct from the telecine” (Bottenberg, incidentally, is also an artist and graphic novelist, co-creator with Claude Lalumiére of the Lost Myths multimedia fictions). Then he introduced Oshii, describing him as one of the key figures in bringing anime to an international audience by his pioneering of the OVA (or Original Video Animation) form. The crowd rose in a standing ovation as the director took the stage.

Oshii turned out to be a lively, unpredictable, and very funny speaker. He said, through a translator, that he’d only watched the film once since it was made: “I tend not to watch any of my old movies after I make them.” (All quotes here, incidentally, from notes I scribbled as he spoke.) He remembered seeing a screening at “some college” in San Francisco, where the film was so old “all you saw was the rain.” Apparently there were only two prints of the film in the United States, and that copy was missing scenes: “It was really hard to tell what kind of story it was. Today I’m praying that you get to see everything.”

Bottenberg then presented Oshii with his Lifetime Achievement Award, a statue of a pegasus. Oshii lifted it up in triumph, and after a bit of clowning when he set it momentarily on his head, sat for a brief interview conducted by Bottenberg. The first question was how it felt to have directed a film that, unlike so much sf cinema, had not become dated. “Each movie has its own lifespan,” Oshii answered, “and I feel that once it doesn’t play on the screen any more, it’s probably dead. … Even if you were to see an article about the movie, that’s the end of its lifespan. Fortunately, my movies usually play once a year somewhere. So as a director it makes me happy to know it’s out there playing.”

Bottenberg then asked about Oshii’s approach to adapting Masamune Shirow’s manga to the screen, and what changes had to be made to the adaptation. Oshii immediately answered: “The biggest difference … was to reduce the size of the boobs.” This got a laugh from the crowd, and Oshii continued slightly more seriously by observing that the most important thing in adaptations is the relationship of the director and the original writer. He recalled how as a young director he had a horrible relationship with Rumiko Takahshi, the original creator of Urusei Yatsura. “I remember fighting with her at least three times … I watched the movie with Rumiko Takahashi and she didn’t even speak to me. I tried to ask her how she felt about my movie, and she wouldn’t even look at me. Whereas Masamune Shirow was a nice guy. I only met him once, though.” Oshii explained that Shirow is a somewhat mysterious figure, who’s never released a photograph of himself. “Maybe the only two directors who know his face are me and Kenji Kamiyama [director of the Ghost in the Shell: Stand Alone Complex TV series]. Kenji Kamiyama had a big fight with Shirow-san. Because I only saw him once I didn’t fight with him.”

Bottenberg then asked about Oshii’s approach to adapting Masamune Shirow’s manga to the screen, and what changes had to be made to the adaptation. Oshii immediately answered: “The biggest difference … was to reduce the size of the boobs.” This got a laugh from the crowd, and Oshii continued slightly more seriously by observing that the most important thing in adaptations is the relationship of the director and the original writer. He recalled how as a young director he had a horrible relationship with Rumiko Takahshi, the original creator of Urusei Yatsura. “I remember fighting with her at least three times … I watched the movie with Rumiko Takahashi and she didn’t even speak to me. I tried to ask her how she felt about my movie, and she wouldn’t even look at me. Whereas Masamune Shirow was a nice guy. I only met him once, though.” Oshii explained that Shirow is a somewhat mysterious figure, who’s never released a photograph of himself. “Maybe the only two directors who know his face are me and Kenji Kamiyama [director of the Ghost in the Shell: Stand Alone Complex TV series]. Kenji Kamiyama had a big fight with Shirow-san. Because I only saw him once I didn’t fight with him.”

He went on to reflect that in adapting a manga to the screen the movie is like a bowl. Put in too much, and it overflows. “But you can’t have it empty, either.” He said that he felt his 2008 film Sky Crawlers fit the bowl perfectly.

The interview turned into a brief question-and-answer period with the audience, and someone asked about his opinion on the Ghost in the Shell TV show, at which Oshii laughed madly. “It’s kind of hard to say here … Kenji Kamiyama [director of the show] is actually one of my disciples, but I don’t remember teaching him anything. Honestly speaking, I haven’t really watched the series.” Still, he said that he understood that there were some differences between how he saw the characters and how the TV version presented them. Oshii said his take on the main character was more passionate and destructive. “I like women who are passionate and destructive,” he reflected.

The interview turned into a brief question-and-answer period with the audience, and someone asked about his opinion on the Ghost in the Shell TV show, at which Oshii laughed madly. “It’s kind of hard to say here … Kenji Kamiyama [director of the show] is actually one of my disciples, but I don’t remember teaching him anything. Honestly speaking, I haven’t really watched the series.” Still, he said that he understood that there were some differences between how he saw the characters and how the TV version presented them. Oshii said his take on the main character was more passionate and destructive. “I like women who are passionate and destructive,” he reflected.

He went to joke about a ‘conflict’ with Kamiyama over what became Kamiyama’s anime movie 009 Re: Cyborg. “I wanted to teach him how to run away from a project,” said Oshii. “It’s actually pretty easy. … Anybody can do it. All you have to do is flip the table over.”

Asked if there were any mangas he had read recently that he wanted to adapt, Oshii answered that he hadn’t been reading mangas over the last three years, and only went to theatres once a year. “I don’t like going to movie theatres,” he explained. He said he’d seen one movie, while he was in Toronto. “I think it’ll be the first and last movie I’ll see this year: Godzilla.”

He then explained that he was in fact in Montreal to work on post-production of his new movie, and that he had just finished the final mix “about an hour ago.” He said he hoped it’d be released next year. Shot in Montreal and Vancouver, it’s called Garm Wars: The Last Druid — and he’d brought a trailer. He explained it was a rushed trailer, especially for Fantasia: “So please don’t videotape this. And after you see it, forget it.”

It’s frankly difficult to forget. The trailer was a mix of wild science-fictional images, some set in a lush and majestic forest, some set in an elaborate high-tech indoor setting. Fighter aircraft whipped across the sky, metallic yet with an oddly organic design. Black-armoured soldiers blasted guns. A ghostly silver girl, her back against a massive tree, stared out of the screen. Dialogue was in English (and the IMDB confirms that it’ll be an English-language film). What we saw was colourful, quick, and evocative; something to watch for, whenever it comes along.

It’s frankly difficult to forget. The trailer was a mix of wild science-fictional images, some set in a lush and majestic forest, some set in an elaborate high-tech indoor setting. Fighter aircraft whipped across the sky, metallic yet with an oddly organic design. Black-armoured soldiers blasted guns. A ghostly silver girl, her back against a massive tree, stared out of the screen. Dialogue was in English (and the IMDB confirms that it’ll be an English-language film). What we saw was colourful, quick, and evocative; something to watch for, whenever it comes along.

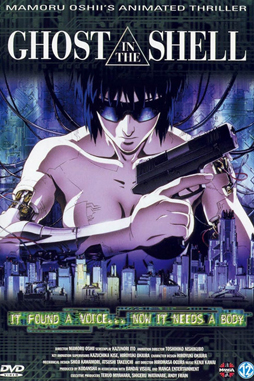

Immediately after the trailer ended, Ghost in the Shell began. As promised, it was a crisp, vibrant print. Small visual details were sharp. This was the original version of the film, not the “2.0” version released in 2008. It’s one of the greatest works of cyberpunk cinema ever made, a quick, complex tale about brains linked to computers, computers messing with organic memories, near-future cyborg killers working for the Japanese government, and an enigmatic hacker ‘puppet master’ with mysterious plans. A violent, bleak tale about the interface of the human and the electronic, it’s a stylish summation of cyberpunk themes.

Interestingly, sitting next to me happened to be a film writer with another web site — Panorama-cinéma, well worth checking out if you read French — who told me after the showing that the subtitles were very different from previous versions of the film. I note that a 25th anniversary Blu-Ray edition of the movie (marking the 25th anniversary of the original manga, that is) has been announced for September 30, so it’s possible that the film was retranslated for that. If so, I hope they give the translation another edit; there were some obvious grammatical errors. It does seem, though, that they’ve fixed one notable translation issue — early on in the film, cyborg Major Kusanagi ironically tells another character that “I must be on my period.” Apparently the first English dub changed this to “I must have a wire loose.” What seems like throwaway snark in the original actually foreshadows some of the film’s main themes: the conflict of flesh and machine, the possibility of mechanical reproduction.

One way or another, the film remains compelling watching. Bottenberg was quite right; Oshii’s 1995 vision of the future — the film’s set in 2029 — hasn’t dated at all (give or take the occasional mullet). The characters’ connection to a mental network may even feel more natural now that smartphones are ubiquitous and everything’s wireless. We can understand the film a bit better — at least, up to a point. The climax depicts an approach to transcendence that is meant to be beyond the human. We can watch it, but what we make of it must vary.

One way or another, the film remains compelling watching. Bottenberg was quite right; Oshii’s 1995 vision of the future — the film’s set in 2029 — hasn’t dated at all (give or take the occasional mullet). The characters’ connection to a mental network may even feel more natural now that smartphones are ubiquitous and everything’s wireless. We can understand the film a bit better — at least, up to a point. The climax depicts an approach to transcendence that is meant to be beyond the human. We can watch it, but what we make of it must vary.

One thing that struck me about the film, this time around, was its sexlessness. This is surprising, perhaps, in that the female lead begins the film by disrobing and spends several key scenes naked. But those first detailed nude images of the Major in fact demonstrate that her artificial body’s lacking sex organs. Sex is messy meat nonsense, unnecessary for superheroic supercompetent cyborgs. So the Major in fact strips naked to activate her optical camouflage, to become invisible — literally, she takes off her clothes as a means to evade the (male) gaze. Mere mortals are playthings; the puppet master cruelly manipulates one simple human being by shaping his memories and making him believe he has a daughter when in fact he’s been living alone for years. Still, the impulse for sex remains, after a fashion — the basic need to splice DNA, to unite and thus to evolve, to create something new and die. But it’s become something utterly different, transposed to a more conceptual, even spiritual level. Thus the film’s end, tragic and uplifting and enigmatic at once.

It’s all very visually striking as well, smoothly animated and lushly designed. The film’s built of breathtaking image after image. An extended wordless sequence of Kusanagi walking through a rainy city is haunting. But more than beautiful, the movie’s also somehow credible. The technology of this future feels liveable. Even the guns have a practicality to them. You see their mechanisms working, the way they eject spent magazines and accept new ones.

Stumbling out of the theatre and back into the twenty-first century as it is, I had the sense of seeing the city with new eyes. It’s something really fine cinema can do, making you see familiar things in new light. In this case, going from watching 1995’s idea of 2029 to the actuality of 2014 left an odd overlay on the urban spaces around me; if nothing else, I was suddenly acutely aware of how much had changed around me in almost twenty years since the movie was released — and since Fantasia was founded. It’s the sort of radical recontextualising of vision I’m hoping to feel often over the next three weeks.

(The second instalment of my Fantasia diary, looking at Kite and Open Windows, is here. The first part of my discussion of Day 3, Saturday June 19, is described here, with reflections on The Satellite Girl and Milk Cow, Demon of the Lute, and Patch Town. I write about my Saturday evening here, discussing Han Gong-ju and Thou Wast Mild and Lovely. I take a close look at Terry Gilliam’s excellent The Zero Theorem here, and here I write about three other movies I saw the same day: Jellyfish Eyes, In the Land of the Head Hunters, and The Reconstruction of William Zero. Here is a consideration of three genre films: Cold in July, The Fatal Encounter, and The Huntresses. Here I take a close look at The Guardians of the Galaxy. Here‘s a look at Faults, and an adaptation of Robert Heinlein’s “All You Zombies …” called Predestination. I look at two science fiction films here, a comedy called The Infinite Man and a drama called Closer to God. Here I write about a martial-arts film called Once Upon a Time in Shanghai, and an animated film called Jack and the Cuckoo-Clock Heart. Two animes, Hal and Giovanni’s Island, are discussed here, while two documentaries, To Be Takei and The Creeping Garden, are discussed here. I look at Cybernatural, The House at the End of Time, and Time Lapse here. Here I look at Korean animated movie The Fake and the two Thermae Romae movies. I look here at Real, the manga adaptation Black Butler, and The One I Love. When Animals Dream, Space Station 76, and Welcome to New York are discussed here. I have a look at Kundo: Age of the Rampant and The Midnight Swim here. And my final look back at what I learned from the festival is here.)

Matthew David Surridge is the author of “The Word of Azrael,” from Black Gate 14. His ongoing web serial is The Fell Gard Codices. You can find him on Facebook, or follow his Twitter account, Fell_Gard.

Ghost in the Shell is an amazing movie. And its impact continues to be long-reaching. It was a large influence on The Matrix, for example.

I wish I had seen the movie in a theatre. That sounds like a great festival. Enjoy!

[…] film festival. Fantasia focuses on genre films from around the world, particularly Asia, and I was able to cover 39 of the 160 features they hosted. That link takes you to the first of 19 posts, which discusses a showing of Ghost in the Shell, and […]