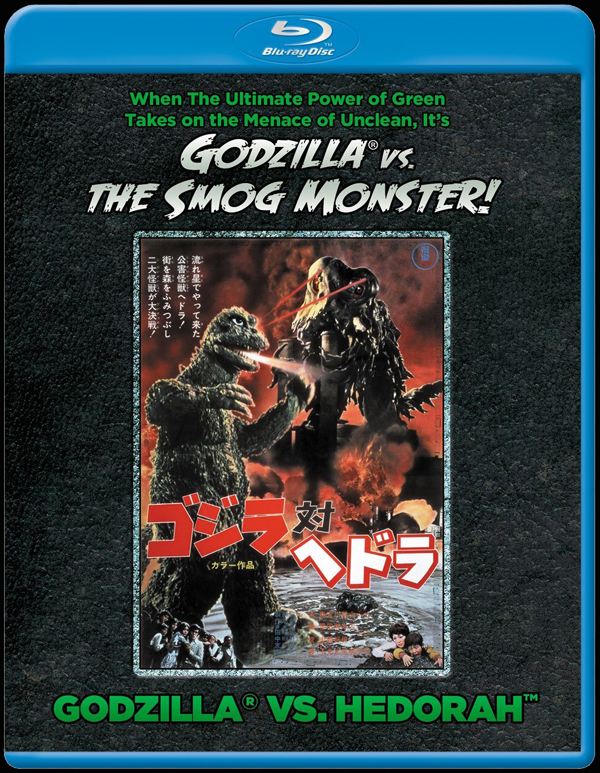

The Godzilla Blu-ray Flood: Godzilla vs. Hedorah (Godzilla vs. The Smog Monster)

This Godzilla film benefits from historical context, so here it be:

In the early 1970s, Japan faced a crisis from increasing pollution due to a massive, unregulated boom in industry across the nation during the previous decade. Poisoning from sulfur dioxide and nitrogen dioxide created a spike in cases of asthma and bronchitis, and respiratory problems in general took a steep rise. The sulfur dioxide poisoning in the city of Yoakkaichi, from refineries built during the 1960s, was so pronounced that it coined a new disease name, Yokkaichi asthma. This caused a ten- to twenty-fold increase in mortality rates among asthma sufferers and led to a 1970 class action lawsuit. Children went to school wearing cotton facemasks, and in the larger cities oxygen tanks were available on the streets for emergency use. In the seas, poor waste management led to a drop in the fishing industry, one of the backbones of the Japanese economy—and fishing rates have continued to drop ever since. A country that once had nuclear power at the forefront of its fears was overwhelmed with a new horror of toxic waste contaminating the air and sea.

All this resulted in Toho Studios releasing a pop art-fueled discotheque of a movie where Godzilla battles a monstrous embodiment of pollution and also learns how to fly. It didn’t solve Japan’s environmental issues, but it has made some people’s lives more surreal.

Godzilla vs. Hedorah (first released in the US through American International Pictures as Godzilla vs. The Smog Monster) was both a movie of its time, focusing on headline-grabbing pollution issues, and a victim of its time, hobbled by the recent implosion of the Japanese studio system and the end of the Toho Visual Effects Department. Director Yoshimitsu Banno, a newcomer to the series, aimed to create a film that recaptured some of the serious allegories of the original 1954 Godzilla. But Banno had to do so in the context of the increasingly kid-centered movies and using limited resources. He ended up with a unique and bizarre film deeply divided against itself, and what would stand as the strangest Godzilla movie of all until Final Wars lurched along in 2004.

The oddball nature of Godzilla vs. Hedorah has earned it a more cultish devotion than some of the better films of the series. No doubt, this is an interesting film, and it shows effort from the creative people involved to produce something memorable. This makes it more admirable than the two quickie installments that followed, Godzilla vs. Gigan and Godzilla vs. Megalon. But the movie’s case of dissociative identity disorder, where it feels as if different films were tossed into a blender that didn’t stay on long enough to mix them well, ends up making it more of a curiosity. Bringing the film down further is a rock-bottom budget that reduces the thrills Godzilla films are supposed to have.

Godzilla vs. Hedorah contains these three movies, all with different tones:

- Standard kaiju movie with a scientist trying to find a way to stop a monster with the assistance of the military.

- Frightening, horror-tinged allegory with the aim of raising awareness about air and water pollution.

- Colorful, psychedelic pop-art entertainment for kids and teens.

The first movie is bland, with no sense of scope, and has monster fights that are too cheap and poorly staged to work well. The second movie is sometimes freakishly effective, with a massive death toll and gruesome, repulsive visuals that strike home about the consequences of industrial pollution; but the movie also turns preachy and offers nothing beyond the surface of “pollution is bad we should stop it.” The third movie is enjoyable camp and has a rockin’ soundtrack and hilarious monster antics.

I like the third movie the most. It may be camp, but it feels like auteur camp.

But considering Godzilla vs. Hedorah’s reputation for hallucinogenic good times, it contains far too many scenes of “bland scientist explaining stuff” and Godzilla and Hedorah standing far apart from each other on empty fields doing nothing but making noise. The appealing antics like Godzilla saving the world at a young boy’s beck and call and teens breaking out an impromptu rock concert at the foot of Mount Fuji (Their amps don’t need electricity?) do not gel with scenes of people dying from sulfuric acid that burns them away to skeletons and Hedorah sludging to death those aforementioned rockin’ teens with toxic mud blasts.

The man behind Godzilla vs. Hedorah’s gumbo of ideas, Yoshimitsu Banno, was a first-time director who started at Toho Studios as a production designer. Banno and special effects supervisor Teruyoshi Nakano (his first film as VFX head in the wake of Eiji Tsubaraya’s death) essentially had a free hand to make the Godzilla film they wanted, while producer Tomoyuki Tanaka was in the hospital. Banno’s inexperience probably accounts for the crazy quilt of the film, and Nakano was more than willing to dive into some of the stranger ideas that Banno hatched for the visuals.

Godzilla vs. Hedorah launches into its split tone from the first. The movie starts with images of filth floating on the water, which then introduces colorful acid blotches that lead into the groovy song “Bring Back Nature” (better known to U.S. audiences in its English version, “Save the Earth”). The song reappears later inside a psychedelic nightclub where Yukio (Toshio Shibaki) watches his girlfriend Miki (Rikako Asa) dance and sing while wearing a skin-colored body suit decorated with sea creatures. The walls of the nightclub come to life with dancing skeletons on a blood-red backdrop, and then Yukio hallucinates that everyone in the club has fish heads.

This is the largest concentration of “strange” in the movie, but similar moments are sprinkled throughout the running time. Most notable are the animated segments, which show things like Hedorah drinking from an oil tanker like it was a pint glass, an industrial factory using pincer claws to snuff out any signs of green that appear on the ground, and a grotesque moment of pollution clouds zapping humans into white silhouettes, two of which then merge together to change into the live action as an area on a map marking Hedorah’s destruction. The young child hero, Yukio’s nephew Ken (Hiroyuki Kawase), has an unexplained telepathic connection with Godzilla which results in dreams and visions that further indulge in jagged imagery.

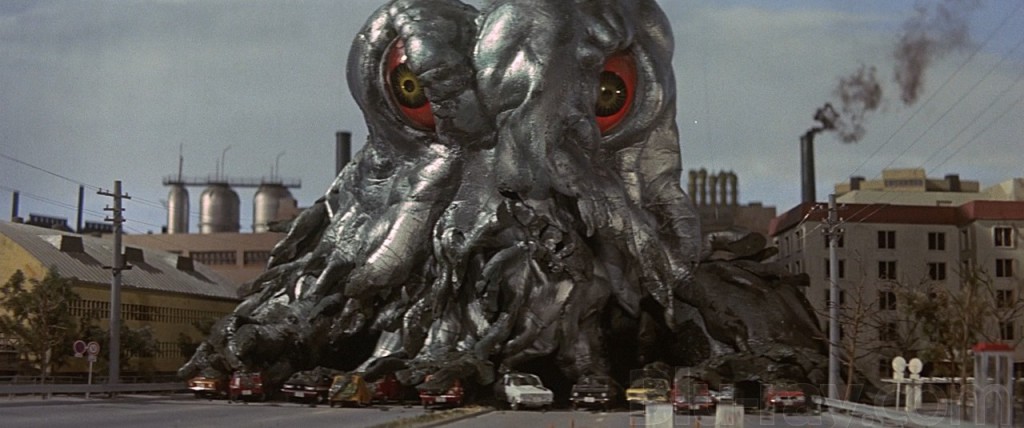

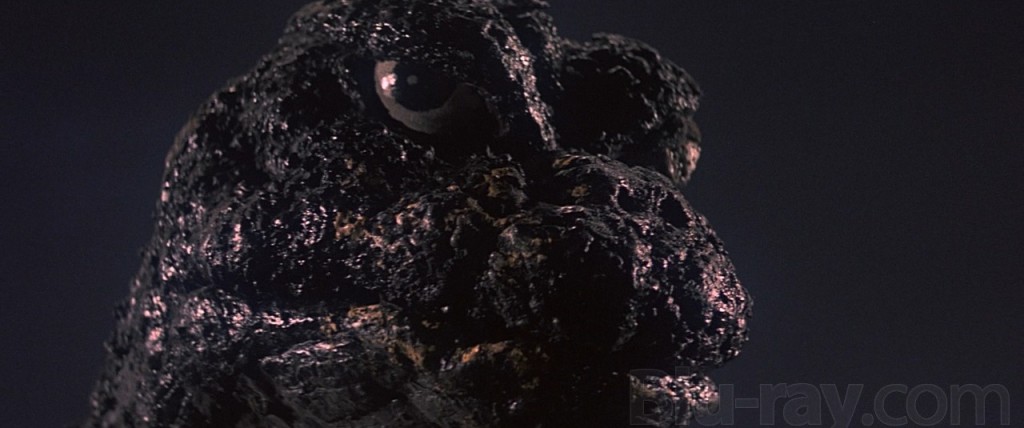

Hedorah is one of the better monsters from the post-studio system era, although with all the brownish goo it keeps emitting I would recommend you refrain from eating while watching it in action. The creature manages to stride the three separate divisions of the movie without stretching, and that makes Hedorah the closest thing the film has to a glue. Hedorah is an effective opponent against Godzilla, acts and looks somewhat silly, and can be truly horrifying.

Hedorah has multiple stages (tadpole, quadruped, flying, biped) that keep it visually interesting. This multi-stage design would become a trademark of the later Heisei films, and Hedorah is clearly the model for those. The arsenal of weapons it pulls out against Godzilla keeps it fun to watch and make it a legitimate danger for the Big G. Hedorah almost defeats Godzilla in an icky sequence where it dumps Godzilla in a pit and starts flooding it with noxious ooze. The effects of Hedorah’s sulfur oxide emissions on people is extremely nasty, realized with grotesque makeup that recalls radiation burn victims.

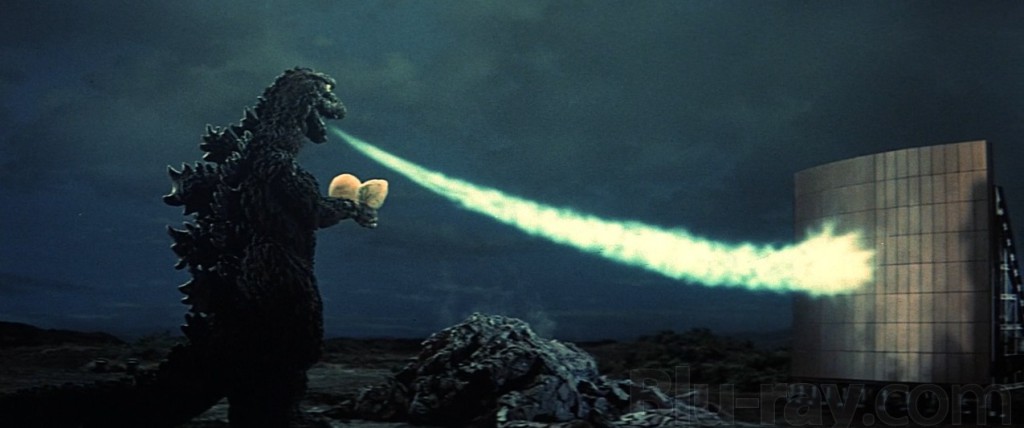

Godzilla completes the transformation to superhero that started in Ghidorah, The Three-Headed Monster seven years earlier. Although Godzilla still causes collateral damage, nobody seems to mind that now. A letter from a 2nd-grade boy says that Godzilla will grow angry over all the pollution in the seas and come do something about it, and as if this summons went out to the big monster personally, Godzilla simply comes ashore to Japan for the sole purpose of defeating Hedorah. Godzilla even knows the Japanese Self-Defense Force’s plans and specifically helps them get their anti-Hedorah electrode machine started when they blow fuse.

To accompany the full superheroizng of Godzilla, the monster acts more anthropomorphized than ever before. In his penultimate appearance in the Godzilla suit, stuntman Haruo Nakajima gives an animated turn that features Godzilla pulling specialty moves like a Ultraman-block, and action-movie character tics like wiping a hand across the mouth and then making a “phooey!” gesture. (Ken imitates this move a few times to cheer Godzilla on.) It’s a performance appropriate for the child-friendly parts of the movie, as is the most notorious scene in the film, when Godzilla learns to fly by using its atomic breath like a jet. Director Banno has admitted pulling this audacious and ludicrous stunt was part of trying to lighten up the film … and it certainly achieves that. The flying gag is so hilarious that it is either one of the best moments of the movie or one of the worst moments of the entire series.

But despite the appeal of both monsters on the fight card, 75% of the VFX sequences are overlong and cheap-looking. Nakano manages a few impressive special effects, such as Hedorah causing the metal frame of a skyscraper under construction to fall apart from its corrosive acid. But Nakano was not at the level of talent of Eiji Tsubaraya, and had far more limited resources with which to work. The excitement audiences anticipate from the effects scenes of a kaiju film rarely emerge.

The first face-off between Hedorah and Godzilla, which takes place in the middle of an industrial port, is a good example of the disappointing monster action. Viewers will expect massive building destruction to occur, with Godzilla and Hedorah throwing each other into smokestacks and warehouses. But little of that occurs, and the enemies spend too much time standing far apart from each other. Even Godzilla swinging Hedorah around by the tail only results in a single slime ball smashing through a window. It nastily kills a group of Mahjong players, which is striking to see, but this is the only jolt in the scene. The other fights take place in empty fields against dark blue backdrops, and refrain from monster tussles and stick to distance attacks and posing.

In an example of poor planning, Godzilla ends up pulling the same trick twice: trapping Hedorah between the giant electrodes the JSDF set up to fry it, then chasing after the escaping smog monster and dragging it back to the electrodes to repeat the process. At least Godzilla’s final victory has our favorite monster tearing Hedorah into tiny pieces and throwing the gooey bits everywhere. That’s good Godzilla fury right there, and watching the monster march off to the sea satisfied with another thrashing well done is a classic kind of Big G moment and one that Gareth Edwards captured perfectly with the recent movie.

The damage from the low budget isn’t limited to the monsters, unfortunately. Because there were no funds for massive crowd scenes, military maneuvers, or panic in the streets, the epic events of a smog monster threatening all life in Japan are reduced to news broadcasts and animated interpolations. A planned “Million March on Fuji” to protest Hedorah (I’m not sure what it was supposed to accomplish, but it sounds fun) ends up attracting only thirty or so for an impromptu rock concert, and that’s the largest gathering of people at any point in the movie. There are no scenes in impressive laboratories with scientists and military officials trying to find a way out of the emergency; instead, Dr. Yano (Akira Yamauichi) mopes around his modest country house, tinkering with a consumer chemistry kit, and occasionally calling the Japanese Self-Defense Force with advice.

The JSDF appears to have suffered from budget cuts as well, since it consists of two helicopters (or one helicopter used twice), four jeeps, and ten soldiers. When you think of how director Ishiro Honda and special effects technician Eiji Tsubaraya would have handled this scenario back in the better-budgeted 1960s, Godzilla vs. Hedorah’s poverty becomes even more disheartening. It does explain why the next two films indulged in so much stock footage, since re-using scenes from the wealthier days can present the illusion of a massive military response to the monsters. But this is a case of a solution to a problem turning into an even bigger problem.

Yoshimitsu Banno was proud of Godzilla vs. Hedorah and planned to direct a follow-up (“And Yet Another One?” a final title card asks ominously), but it was not to be, as producer Tanaka hated the results when he got out of the hospital and actually saw what Banno and Nakano had been doing. Banno recalls Tanaka saying, “You have ruined Godzilla!” The producer probably did say something pretty close to that, because Banno never directed another Godzilla film and mostly worked on documentaries after this. However, he remained part of the Godzilla legacy. Banno developed ideas for an IMAX Godzilla film in the late 2000s, and that project—through many twists and turns—ended up at Legendary Films where it became the 2014 Godzilla. Banno received credit as Executive Producer on the new movie, making him the only classic era Godzilla director involved with the U.S. film.

I hesitate in recommending Godzilla vs. Hedorah as viewing for younger children; when it turns on the horror, the movie doesn’t hold back, and some children will find these segments extremely disturbing. If you feel on the fence about how your kids may react to these scenes, preview the movie first. For young viewers who can handle the harsher aspects, Godzilla vs. Hedorah should really jazz them up with its colorful antics and cool monster stars, and they’ll sail through the more tepid parts of budgetary problems with more ease than adult Godzilla fans will.

The Blu-ray from Kraken Releasing is another fine transfer that makes the colors pop, although the source appears in poorer condition than that used for Ebirah, Horror of the Deep. The English dub available on the second channel is the International one that Toho commissioned from Frontier Enterprises for English-language territories; this is the same one from the Sony DVD. Viewers who grew up with broadcasts of the AIP version, Godzilla vs. The Smog Monster, will be disappointed with the unfamiliar (and poorer quality) dub, but the rights to the AIP version currently float in limbo. The Blu-ray dub doesn’t include the beloved “Save the Earth,” the English-lyric version of the song “Bring Back Nature” that AIP recorded for their release. The song is presented in Japanese without subtitles. You’ll have to go to YouTube to hear the English version.

Ryan Harvey is one of the original bloggers for Black Gate, starting in 2008. He is a recipient of the Writers of the Future Award and is the author of Turn Over the Moon.

The movie is terrible.

But it is also one of the first Godzilla movies I ever saw and it has a special place in my heart. It is so freakishly weird. Plus that soundtrack is like an ear worm.

On a tangentially-related note, did you see they announce Blu-ray releases of the rest of the Millenium series, plus all three Rebirth of Mothras?

I watched this one for the first time ever a few weeks back. It’s terrible! But it’s groovy!

That’s a good summary.

I’ve already pre-ordered all the new releases that Sony announced today. It’s weird to have the two Mechagodzilla films on separate sets (and why release the second film first?) but as long as they’re all together.

This means we’re missing The Return of Godzilla from the Heisei movies, and a still significant chunk from the Showa films. The next film to come out is Godzilla vs. Megalon in two weeks (joy).

I have a soft brain — I mean spot — for Megalon just because it’s the first Godzilla movie I ever saw. On TV, as I recall.

I think Return is the only one now that’s wholly unavailable — everything else is on DVD, at least.

I also do like the Mothra movies — they’re fun children’s fantasies. And III has the four-legged Ghidorah.

Yes, The Return of Godzilla has not been available in the U.S. in any format since the VHS tape from Lakeshore in 1997, which of course was the Godzilla 1985 version. Lakeshore announced a DVD in 2004, but Toho blocked them because their rights had expired. Whoever wants to release the film in the U.S. will need to negotiate a new deal with Toho. When that does happen, I imagine we’ll see something similar to the upcoming Godzilla 2000: Millennium Blu-ray, with both versions on one disc.

Although King Kong vs. Godzilla has long been on DVD (and now Blu-ray), it has never had a release in its Japanese version in the U.S. Once the Godzilla 2000 Blu-ray comes out, the only films without a DVD or Blu-ray release with the original Japanese language tracks will be King Kong vs. Godzilla and The Return of Godzilla.

That’s right — we’re also missing good versions of King Kong vs. Godzilla (and the second Toho King Kong movie, for that matter).