Blogging Sax Rohmer… in the Beginning, Part One

“The Mysterious Mummy” marked Sax Rohmer’s first appearance in print. Only 20 years old at the time, Rohmer was then writing under the byline of A. Sarsfield Ward. Born Arthur Henry Ward, Sarsfield was a surname of historical repute from his mother’s side of the family, which he adopted at the start of his writing career.

“The Mysterious Mummy” marked Sax Rohmer’s first appearance in print. Only 20 years old at the time, Rohmer was then writing under the byline of A. Sarsfield Ward. Born Arthur Henry Ward, Sarsfield was a surname of historical repute from his mother’s side of the family, which he adopted at the start of his writing career.

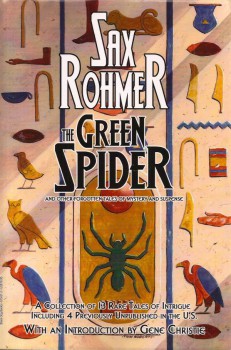

A preview of the story was featured in the November 19, 1903 issue of Pearson’s Weekly, with the full story printed in the November 24 issue. “The Mysterious Mummy” languished in obscurity until it was reprinted by Peter Haining in the 1986 anthology, Ray Bradbury Introduces Tales of Dungeons and Dragons. Haining also included the story in the 1988 anthology, The Mummy: Stories of the Living Corpse. Rohmer scholar Gene Christie selected the story for inclusion in the first volume of Black Dog Books’ Sax Rohmer Library, The Green Spider and Other Forgotten Tales of Mystery and Suspense, published in 2011.

The most interesting feature about this first foray into fiction is that it is not at all a living mummy story, but rather a straight heist caper. Rohmer later disingenuously claimed that a copycat theft was attempted in France and the thief was arrested with a copy of Pearson’s Weekly on his person, featuring the story which he claimed was so good he had to risk trying it in real life. Rohmer, of course, was a terribly unreliable interview subject. While it is possible the press were more gullible a century ago, it is more likely they viewed his tall tales as good copy.

From the standpoint of the modern reader, “The Mysterious Mummy” is not particularly thrilling. Considering his young age, it is evident Rohmer was well-read and showed a gift for story-telling and an appreciation for viewing the world from dark corners. It is simply a straightforward heist tale in which a thief robs a museum of a valuable Egyptian vase by hiding inside an empty sarcophagus on display after first wrapping himself up as a mummy. The influence of Conan Doyle on the writing style is evident, but there is no Sherlock Holmes to unravel the mystery, as Rohmer wants his thief to get away with the crime by outsmarting the authorities.

As an aside to fans of Rohmer’s later Fu Manchu series, the small cast of characters includes an attendant of the Egyptian room called Barton, as well as a constable called Smith. While there is no reason to connect them to the Fu Manchu series’ celebrated Egyptologist Sir Lionel Barton or the series’ stalwart protagonist Nayland Smith, it is interesting that Rohmer associated the names Barton and Smith with Egypt and the police, respectively from the very beginnings of his writing career.

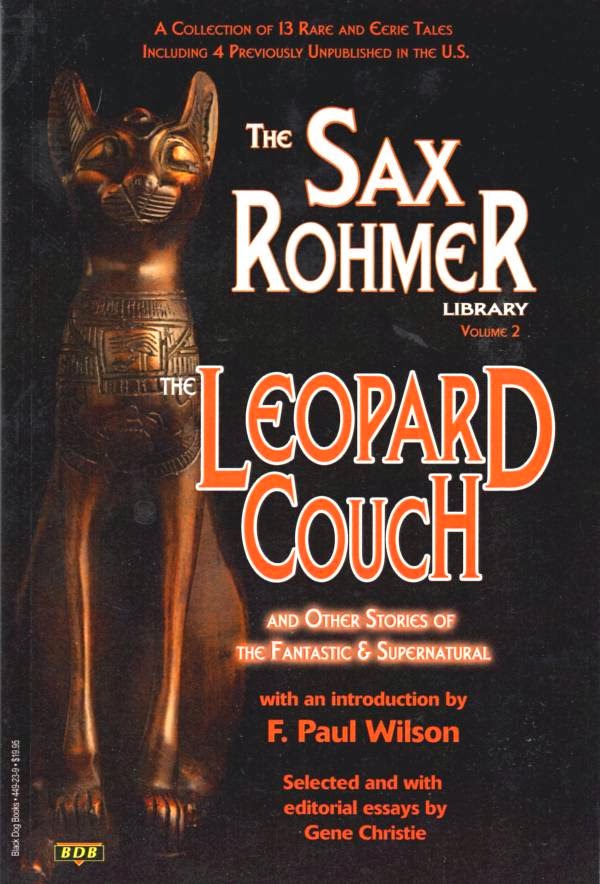

“The Leopard Couch” was the second story Rohmer sold. Also published under the byline of A. Sarsfield Ward, the story first appeared in the January 30, 1904 issue of Chamber’s Journal. Rohmer scholar Robert E. Briney rescued it from obscurity for inclusion in The Wrath of Fu Manchu and Other New Stories, a 1973 collection of Rohmer’s short fiction that had never before appeared in book form. More recently, Gene Christie included the story in the second volume of Black Dog Books’ Sax Rohmer Library, The Leopard Couch and Other Stories of the Fantastic and Supernatural, in 2012.

“The Leopard Couch” was the second story Rohmer sold. Also published under the byline of A. Sarsfield Ward, the story first appeared in the January 30, 1904 issue of Chamber’s Journal. Rohmer scholar Robert E. Briney rescued it from obscurity for inclusion in The Wrath of Fu Manchu and Other New Stories, a 1973 collection of Rohmer’s short fiction that had never before appeared in book form. More recently, Gene Christie included the story in the second volume of Black Dog Books’ Sax Rohmer Library, The Leopard Couch and Other Stories of the Fantastic and Supernatural, in 2012.

While written at approximately the same time as “The Mysterious Mummy,” both stories having been submitted to editors simultaneously, “The Leopard Couch” is by far the stronger of the two. A traditional first person narrative account of an Egyptologist’s undeniable brush with the occult, the story shows the influence of both Bram Stoker’s Jewel of the Seven Stars (published only a few months before this story was written) and Guy Boothby’s recent Pharos the Egyptian (1899). The Egyptian curio of the title appears cursed, having brought death to its two most recent owners before coming into the possession of the two Egyptologists who unravel its mystery.

The most significant portion of the story is the narrator’s astral voyage back in time to ancient Egypt, while reclining on the mystical leopard couch, where he witnesses a tragedy of star-crossed lovers who ran afoul of a vengeful religious cult (suspiciously similar to the flashback sequence that later appeared in Universal’s 1932 horror classic, The Mummy, starring Boris Karloff).

Rohmer was understandably elated by the fact that his very first story submissions saw publication. He immediately set to work upon a novel with an Egyptian theme entitled Zalithea. He abandoned the work after several chapters, but later claimed in his serialized memoirs, Pipe Dreams (1938), that what he did write of the book was the result of an astral voyage to ancient Egypt, where he encountered the dancing girl, Zalithea, and was later visited by her spirit in his bedroom that same night.

The similarity of this fantastic episode with the literary events of “The Leopard Couch” should not be discounted, particularly since the earlier story was not reprinted in Rohmer’s lifetime. It is rather similar to his claims that a real-life Chinese gangster called Mr. King inspired Fu Manchu after his attempt at creating a more realistic Chinese villain called Mr. King for his novels, The Yellow Claw (1915) and Yu’an Hee-See Laughs (1931), failed to supplant the Devil Doctor in popularity.

As for Zalithea, the dancing girl of Egypt who never made it to book form,; bits and pieces of this unfinished work found their way into Rohmer’s later novels, The Green Eyes of Bast (1920) and She Who Sleeps (1928). Whether writing fiction or telling tall tales, Rohmer was never one to discard a good story.

William Patrick Maynard was authorized to continue Sax Rohmer’s Fu Manchu thrillers beginning with The Terror of Fu Manchu (2009; Black Coat Press) and The Destiny of Fu Manchu (2012; Black Coat Press). The Triumph of Fu Manchu is coming soon from Black Coat Press.