Medea

Lately in this space I seem to be writing a lot, one way or another, about worldbuilding. As it happens, I also read a book not long ago which both imagines a detailed science-fictional world and determinedly lifts the curtain on the group act of creation that generated the world. The book is Medea: Harlan’s World, and there are some interesting things to take away from it — not just ideas about worldbuilding, either.

Lately in this space I seem to be writing a lot, one way or another, about worldbuilding. As it happens, I also read a book not long ago which both imagines a detailed science-fictional world and determinedly lifts the curtain on the group act of creation that generated the world. The book is Medea: Harlan’s World, and there are some interesting things to take away from it — not just ideas about worldbuilding, either.

Medea is in the lineage of shared-world books, though Ellison, who has expressed disdain for shared worlds, would likely dispute that; at any rate, it was originally conceived in 1975, but not published as a whole until 1985, so was imagined before Thieves’ World or Wild Cards or Liavek, before the articulation of the ‘shared world’ as a specific kind of endeavour. Perhaps ironically, Medea would spawn a kind of conceptual sequel, Murasaki, edited by Robert Silverberg, one of the participants in the Medea collaboration. Medea‘s an anthology of stories by different writers, all set on what is notionally the same science-fictional planet. Many of the individual stories were highly praised. Ellison’s “With Virgil Oddum at the East Pole” was selected for inclusion in The 1986 Annual World’s Best SF; Larry Niven’s “Flare Time” placed ninth in that year’s Locus poll for best novella; Frederik Pohl’s “Swanilda’s Song” placed fourth in the novelette category; Poul Anderson’s “Hunter’s Moon” won the Hugo Award for Best Novelette. Whether they work well together is in the eye of the beholder.

It doesn’t much read like the typical shared-world anthology. Ellison’s quite specific about that in his introduction, where he describes an editorial process that gladly welcomed individual takes on the basic concepts of the fictional world, even encouraging contradictions between stories: “Not only do I admit to the contradictions in these yarns, I champion them!” It probably does help give the book an idiosyncrasy unlike many shared worlds; the problem, I found, was that the individual stories were of varying quality (as one would expect of an anthology), none were really excellent, and they didn’t seem collectively to create a real unity out of the book. Then again, I also thought Medea as a whole was well worth reading for the extensive look at the creative process behind the making of the fictional world, and indeed for the look it gives us at a specifically science-fictional kind of creativity.

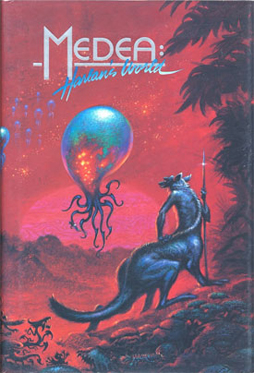

As Ellison describes it, the genesis of the book came about from a series of lectures he gave at UCLA in 1975. For one of the lectures he decided to present a panel of science-fiction writers jointly brainstorming story ideas in front of the audience. Well beforehand, Ellison approached Hal Clement to create the basic astronomical details of a fictional planet (actually a moon in the Alpha Geminorum system), then had Poul Anderson create details of the world’s oceans, weather, geology, and biology, as well as create names for moons, planets, and significant terrain features (Anderson picked “Medea” because the world is in the system of the stars Castor and Pollux, who were Argonauts; it’s an apt choice, since the Argonauts, as Black Gate readers know, are an assemblage of heroes with their own stories all coming together into one, something at least vaguely akin to this sort of shared world). Larry Niven then elaborated on Anderson’s ideas about the moon’s biology, and worked out further details about the ecology of the world now called Medea. Frederik Pohl came up with a set of ideas about the civilizations and philosophies of the two intelligent races that lived on the alien planet. All this information was combined into a mimeographed booklet, which was then given to artist Kelly Freas, who created an image of life on the surface of Medea based on what the various writers had come up with. On the evening of the lecture, two hours before going on stage, Ellison gave the pamphlet and image to the four writers he’d assembled for the panel: Robert Silverberg, Frank Herbert, Thomas M. Disch, and Theodore Sturgeon. The pamphlet was also handed out to everyone in the audience.

As Ellison describes it, the genesis of the book came about from a series of lectures he gave at UCLA in 1975. For one of the lectures he decided to present a panel of science-fiction writers jointly brainstorming story ideas in front of the audience. Well beforehand, Ellison approached Hal Clement to create the basic astronomical details of a fictional planet (actually a moon in the Alpha Geminorum system), then had Poul Anderson create details of the world’s oceans, weather, geology, and biology, as well as create names for moons, planets, and significant terrain features (Anderson picked “Medea” because the world is in the system of the stars Castor and Pollux, who were Argonauts; it’s an apt choice, since the Argonauts, as Black Gate readers know, are an assemblage of heroes with their own stories all coming together into one, something at least vaguely akin to this sort of shared world). Larry Niven then elaborated on Anderson’s ideas about the moon’s biology, and worked out further details about the ecology of the world now called Medea. Frederik Pohl came up with a set of ideas about the civilizations and philosophies of the two intelligent races that lived on the alien planet. All this information was combined into a mimeographed booklet, which was then given to artist Kelly Freas, who created an image of life on the surface of Medea based on what the various writers had come up with. On the evening of the lecture, two hours before going on stage, Ellison gave the pamphlet and image to the four writers he’d assembled for the panel: Robert Silverberg, Frank Herbert, Thomas M. Disch, and Theodore Sturgeon. The pamphlet was also handed out to everyone in the audience.

Part I of the book Medea is therefore ‘The Specs,’ the text generated by Clement, Anderson, Niven, and Pohl. Part II is a transcription of the panel, including some questions from the audience. Part III is a series of ideas contributed in writing by the audience after the panel. (All the audience contributors are named, and there are a lot of them, so I’d expected to see people who went on to have writing careers; as it turned out, the only name I personally recognised was a ‘Marc Zicree,’ who I have to presume is novelist and TV writer Marc Scott Zicree.) Part IV is a set of ‘Second Thoughts’ contributed by the four writers of the specs, taking issue with some of the ideas the four panelists put forward which seemed to contradict the original plans for Medea. Finally, Part V is made up of the stories themselves.

Part I of the book Medea is therefore ‘The Specs,’ the text generated by Clement, Anderson, Niven, and Pohl. Part II is a transcription of the panel, including some questions from the audience. Part III is a series of ideas contributed in writing by the audience after the panel. (All the audience contributors are named, and there are a lot of them, so I’d expected to see people who went on to have writing careers; as it turned out, the only name I personally recognised was a ‘Marc Zicree,’ who I have to presume is novelist and TV writer Marc Scott Zicree.) Part IV is a set of ‘Second Thoughts’ contributed by the four writers of the specs, taking issue with some of the ideas the four panelists put forward which seemed to contradict the original plans for Medea. Finally, Part V is made up of the stories themselves.

In addition to all the writers thus far involved in the project, Ellison brought in two others to contribute tales, Jack Williamson and Kate Wilhelm: “Jack as the writer a thousand participants voted into the cadre as the one they’d most like to see writing about Medea; and Kate because it became embarrassingly obvious that somehow an all-male view was being presented and, simply put, we needed input from the finest female writer in the genre.” I mean no disrespect to Wilhelm to say that I found that last assessment a little surprising, though in a later interview with the Canadian TV show Prisoners of Gravity Ellison noted that Ursula Le Guin was also approached and did not take part. Prisoners of Gravity in fact dedicated a whole episode to Medea, which contained several fascinating reflections on the book — including Ellison rejecting the idea that having only one woman in the anthology fostered a “boys club” atmosphere, and his stating that “I absolutely despise and abhor, so that there’s no mistake about it, the shared world books that are done. Even when they’re at their best … I think they are anti-art, I think they are anti-talent, I think writers who get involved in them for whatever capricious reasons serve the devil.”

In that Prisoners of Gravity epsiode, Robert Silverberg referred to Medea as a “great book” with no apparent attempt at hyperbole. I found I couldn’t agree with that assessment. It’s a fascinating book, but probably more for the overall package, the look at the creative process. The stories are interesting as showing a variety of styles and approaches, but I felt the story behind the stories overshadowed them.

In that Prisoners of Gravity epsiode, Robert Silverberg referred to Medea as a “great book” with no apparent attempt at hyperbole. I found I couldn’t agree with that assessment. It’s a fascinating book, but probably more for the overall package, the look at the creative process. The stories are interesting as showing a variety of styles and approaches, but I felt the story behind the stories overshadowed them.

The first part, the ‘specs’ of Medea, was only moderately intriguing at first reading: four writers throw ideas at a wall, and rough out a planet. I did find myself wondering whether the discovery of so many exoplanets in the last few years is changing the nature of science fictional creativity — at the time the book was published, no planet outside the solar system was known, so Clement made up Medea and its nearby celestial bodies out of whole cloth. At any rate, the book picks up with the second part, the panel discussion; it’s utterly fascinating. The four writers — five, with Ellison, who as moderator was relatively restrained — threw out ideas, debated, talked over each other, and generally brainstormed a host of ideas some of which made it into their stories and some of which didn’t. In general, you could see storytellers’ minds at work; the writers on the panel were all trying to assimilate the data they’d been given, and find points in it that they could build up into stories. Those stories clashed with the other stories the other writers were imagining, and often clashed with points in the original specs. Themes and ideas were thrown out, worked on, then discarded; there was something almost frustrating about reading the whole process, as perfectly good ideas that seemed to hold much promise were abandoned in favour of what seemed less intriguing — but which hooked one or more of the writers.

It seems to me that Clement, Anderson, Niven, and Pohl are on the whole writers of a harder brand of sf than Herbert, Sturgeon, Silverberg, and Disch (speaking broadly, over the course of these men’s careers). So it’s interesting to see the panel taking issue with the specs of Medea, and insisting on finding higher levels of intelligence in one or both of the races of aliens than the original specs suggested. It’s also interesting to see them build on something mentioned only relatively briefly in the specs, and work out what was happening on the Earth of the future, and how that Earth would relate to the human colony that every writer assumed would be built on Medea (it seemed the panel agreed that they wanted to avoid retelling the settlement of North America, but all imagined some kind of colonial set-up). The ‘Second Thoughts’ that follow the panel then had some interesting rebuttals from the original four writers, insisting on their own ideas. You can already see individual ideas, things that have grabbed hold of the individual imaginations.

It seems to me that Clement, Anderson, Niven, and Pohl are on the whole writers of a harder brand of sf than Herbert, Sturgeon, Silverberg, and Disch (speaking broadly, over the course of these men’s careers). So it’s interesting to see the panel taking issue with the specs of Medea, and insisting on finding higher levels of intelligence in one or both of the races of aliens than the original specs suggested. It’s also interesting to see them build on something mentioned only relatively briefly in the specs, and work out what was happening on the Earth of the future, and how that Earth would relate to the human colony that every writer assumed would be built on Medea (it seemed the panel agreed that they wanted to avoid retelling the settlement of North America, but all imagined some kind of colonial set-up). The ‘Second Thoughts’ that follow the panel then had some interesting rebuttals from the original four writers, insisting on their own ideas. You can already see individual ideas, things that have grabbed hold of the individual imaginations.

Still, the leap from there to actual stories is huge. Elements of these texts appear in the final stories, but they’re really several quantum leaps removed from the original discussions. Themes that seemed powerful in discussion are abandoned or minimised. On the other hand, throwaway ideas take on new life. So a mention in the original specs that Terran bacteria might fend off Medean parasites becomes a character note in Jack Williamson’s “Farside Station,” the opening story of the book — not a plot point, but a side observation about the smell of an unwashed human body in the small space of a van. Here we begin to see a kind of alchemical transmutation of the specs: from random astronomical or biological fact, they become story.

Williamson’s tale is a competent yarn about human settlers trying to make meaningful contact with alien life, a recurring theme in the book. Larry Niven’s “Flare Time” focuses on humans, and the relation of the colony to the broader interplanetary human society; it’s sf focussing on the nature of the future, on how human culture and human beings will change with time. As a story, it’s effective, inventive, and clever without being particularly memorable. Ellison’s “With Virgil Oddum at the East Pole” is a story about art, and again about ambiguous human connections with aboriginal Medeans; it’s got a bit more stylistic dash than Niven’s piece, but is ultimately less surprising.

All these stories took full advantge of the unique imagery and colour sense implied by the specs of Medea; Frederik Pohl’s “Swanilda’s Song” much less so, being essentially a gag story in dubious taste that (to my mind) utterly fails to work. On the other hand, I thought Hal Clement’s “Seasoning” one of the strongest stories in the book, a man-against-alien-nature tale that’s given a touch of the science-fictional sublime by the presence of an ancient alien artefact possessing a kind of artificial intelligence. Thomas M. Disch’s “Concepts” is also a strong piece, much more ironic than any of the other stories and less concerned with Medea: it takes place largely on Earth, and has to do, at least in part, with the difficulty of communication between planets and people. Frank Herbert’s “Songs of a Sentient Flute” is perhaps the most of-its-time of all the stories in the book, a story of a ship-raised naïf becoming a messianic mediator who speaks to aliens “in the no-place, the betweens and in the honesty of the songs.”

All these stories took full advantge of the unique imagery and colour sense implied by the specs of Medea; Frederik Pohl’s “Swanilda’s Song” much less so, being essentially a gag story in dubious taste that (to my mind) utterly fails to work. On the other hand, I thought Hal Clement’s “Seasoning” one of the strongest stories in the book, a man-against-alien-nature tale that’s given a touch of the science-fictional sublime by the presence of an ancient alien artefact possessing a kind of artificial intelligence. Thomas M. Disch’s “Concepts” is also a strong piece, much more ironic than any of the other stories and less concerned with Medea: it takes place largely on Earth, and has to do, at least in part, with the difficulty of communication between planets and people. Frank Herbert’s “Songs of a Sentient Flute” is perhaps the most of-its-time of all the stories in the book, a story of a ship-raised naïf becoming a messianic mediator who speaks to aliens “in the no-place, the betweens and in the honesty of the songs.”

Poul Anderson’s “Hunter’s Moon” is a well-crafted story in which cybernetic telepathic connections with feuding aliens allow two humans to work through their own relationship. Kate Wilhelm’s “The Promise” balances a research scientist’s need to further her own career with, once again, the things to be learned from Medea, including a new kind of mental unity. “Why Dolphins Don’t Bite,” by Theodore Sturgeon, begins with its (male) protagonist being raped and then simply setting the experience aside; it turns into a story about acceptance of otherness and other ideas. I find Sturgeon’s an extremely effective exponent of old-fashioned liberal humanism, and this story is a perfect example of what he does well; it also attempts to question the limits of that humanism, the limits of empathy, and to some extent succeeds. Robert Silverberg’s “Waiting for the Earthquake” wraps up Medea with a story that consciously attempts to tie together all the other stories: in that Prisoners of Gravity show, Silverberg said that his tale was chronologically the last written of the book. It makes for a strong end, bringing a cycle of history to a close, and hinting at some kind of achievement or realisation that had been evaded through most of the rest of the book.

Silverberg also said that he had to grapple with the lack of consistency of the stories when he tied them all together. On a plot level, I didn’t find the conflicts that jarring as I read the book. Medea’s explicitly stated, in the stories and in the background material, to be a planet with many small ecoregions and extremely quick evolution. So the idea that the different alien races have different characteristics in different places is at least plausible. The stories are widely separated in space and especially time, so even the somewhat conflicting ideas of human society can almost work. In fact, there’s a kind of commedia dell’arte feel to the book as a whole, as ideas and images recur in similar roles but with slight differences in different stories. The concepts — the aliens, the colours and skies of Medea — come to illustrate the individual approaches to the material.

Silverberg also said that he had to grapple with the lack of consistency of the stories when he tied them all together. On a plot level, I didn’t find the conflicts that jarring as I read the book. Medea’s explicitly stated, in the stories and in the background material, to be a planet with many small ecoregions and extremely quick evolution. So the idea that the different alien races have different characteristics in different places is at least plausible. The stories are widely separated in space and especially time, so even the somewhat conflicting ideas of human society can almost work. In fact, there’s a kind of commedia dell’arte feel to the book as a whole, as ideas and images recur in similar roles but with slight differences in different stories. The concepts — the aliens, the colours and skies of Medea — come to illustrate the individual approaches to the material.

The problem is that, much as Silverberg tries to tie together all the stories in his concluding tale, there isn’t much thematic unity to the stories. Or, to the extent that there’s unity, there isn’t really development. Some ideas are played with by most of the writers; but these ideas don’t build on each other, or develop across the whole of the work. Ellison would probably argue, with some justice, that that’s the point — the idea is to see the different writers play with things in their own way. To me, the thematic conflict tended less to create a dialogue than to develop interference patterns, static noise like the snow on an old-fashioned TV: voices were not engaging with each other, but talking past one another. So even if there is a strong overall sense of the book having to do with the great staple sf theme of humans interacting with the alien, there is no feel of any resolution or earned conclusion. Again, Silverberg tries to produce one, and comes remarkably close; but when you look past his story on its own, and over the arc of the book, you find there really isn’t much of a thematic arc to speak of.

Still, when all’s said and done, Medea shows something about the scope and nature of science fictional thinking. As the different writers work up the specs, you see their awareness of astronomy and cosmology and geology and biology and any number of other sciences coming together. You see how the science ends up serving the storyteller. And you see just how much diverse learning in how many diverse fields can be used to enrich a fictional creation. It suggests that sf can be seen as an encyclopedic form, potentially as all-encompassing in its learning as an epic poem or Menippean satire. On the other hand, that same encyclopedic sense can also result in the sharp awareness of a given author’s limits.

Still, when all’s said and done, Medea shows something about the scope and nature of science fictional thinking. As the different writers work up the specs, you see their awareness of astronomy and cosmology and geology and biology and any number of other sciences coming together. You see how the science ends up serving the storyteller. And you see just how much diverse learning in how many diverse fields can be used to enrich a fictional creation. It suggests that sf can be seen as an encyclopedic form, potentially as all-encompassing in its learning as an epic poem or Menippean satire. On the other hand, that same encyclopedic sense can also result in the sharp awareness of a given author’s limits.

During the lecture, Silverberg is “hissed” for observing that the females of one of the alien species would have “responsibilities that would prevent them from the luxury of any prolonged journey.” The reason for Silverberg’s assessment is not at all clear to me; one can argue that the biology of the aliens, as given to Silverberg to elaborate, would preclude long journeys, but it’s not a necessary assumption. Ellison defends Silverberg, saying that “while it may go against whatever current cultural ideas you have about sexism or racism or whatever it may be, there are some things that you deal with on the face of it just as they are given.” Silverberg adds “Simply, it is not a cultural idea that the females bear the children.” But, of course, he’s wrong. SF’s filled with trisexual alien races where the egg donor is a different sex from the bearer of the child. In this particular case, Silverberg’s trying to work out the social dynamics of an alien race that begin their lives as females, drop two litters, become male and enter into a rutting frenzy, then end up as post-sexual creatures — in which state, to me, they would seem best equipped for raising the young, thus freeing up the females for long voyages.

I don’t mean to attack Ellison and Silverberg for having had what are now old-fashioned ideas about gender forty years ago. It’s just probably the most obvious example in the book of a writer applying (what he believed to be) human verities to a nonhuman situation. That is, of a writer having his imagination limited by the bounds of societal convention without his realising it. Sturgeon’s meditation on the limits of empathy is relevant here, but not perhaps in the way that he conceived it. However literate and knowledgeable, individual writers necessarily have limits to their individual knowledge. They will have biases and prejudices and fascinations and obsessions of their own; it may be that it is these things, or their interaction, that allow them to generate stories. But they tend also to undermine the writer’s claim to universality — their ability to build a credible world. At best, these limits are invisible. Ironically, the conflicting visions of the different writers of Medea tend to bring the limits of each different vision into focus. The different writers take away from the specs what they want; not much ultimately is shared. The stories, in ignoring each other, unintentionally deconstruct each other: signal, as I said, becomes noise.

I don’t mean to attack Ellison and Silverberg for having had what are now old-fashioned ideas about gender forty years ago. It’s just probably the most obvious example in the book of a writer applying (what he believed to be) human verities to a nonhuman situation. That is, of a writer having his imagination limited by the bounds of societal convention without his realising it. Sturgeon’s meditation on the limits of empathy is relevant here, but not perhaps in the way that he conceived it. However literate and knowledgeable, individual writers necessarily have limits to their individual knowledge. They will have biases and prejudices and fascinations and obsessions of their own; it may be that it is these things, or their interaction, that allow them to generate stories. But they tend also to undermine the writer’s claim to universality — their ability to build a credible world. At best, these limits are invisible. Ironically, the conflicting visions of the different writers of Medea tend to bring the limits of each different vision into focus. The different writers take away from the specs what they want; not much ultimately is shared. The stories, in ignoring each other, unintentionally deconstruct each other: signal, as I said, becomes noise.

Still, the book gives us an example of how sf stories can be put together; of how thought-experiments become stories. It’s a valuable text for the study of science fiction as a genre, I think, illustrating techniques and modes of thought as well as presenting something of a cross-section of where the genre was at a certain point in time. It’s an interesting book, one worth thinking about. It’s difficult, in the final analysis, to classify it as either a success or failure. An experiment, once carried out, is neither success nor failure; it is a data point, a result. So it is for Medea, in form a thought experiment, both like and unlike all those thought experiments that have driven science fiction from its inception.

Matthew David Surridge is the author of “The Word of Azrael,” from Black Gate 14. His ongoing web serial is The Fell Gard Codices. You can find him on Facebook, or follow his Twitter account, Fell_Gard.