“Gamera Is Really Neat!” (Sometimes): The Classic Gamera Series on Blu-ray

The Japanese giant monster world of the 1960s and early ‘70s was about more than Godzilla. It was also about the Frankenstein Monster, dueling Frankenstein Monsters (a.k.a. “Gargantuas”), wrathful stone idols, burrowing Boston Terrier lizards, alien saucer-headed chicken thingies, King Kong, a robot King Kong, huge squids and crabs, Atlantean dragon-gods, and a gratuitous giant walrus.

The Japanese giant monster world of the 1960s and early ‘70s was about more than Godzilla. It was also about the Frankenstein Monster, dueling Frankenstein Monsters (a.k.a. “Gargantuas”), wrathful stone idols, burrowing Boston Terrier lizards, alien saucer-headed chicken thingies, King Kong, a robot King Kong, huge squids and crabs, Atlantean dragon-gods, and a gratuitous giant walrus.

Mixed up in there was a flying turtle who was the friend to all children, Gamera. This airborne Chelonia somehow managed to sustain a seven-film franchise during the Golden Age (plus a strange one-off in 1980), making it the most successful monster after Godzilla, and the only giant monster from a studio other than Toho to make a large impression on audiences outside its home country.

Gamera is Godzilla’s poor stepchild/competitor, but the spinning turtle has leaped into the Blu-ray ring right along with the recent influx of Godzilla films as part of the release of the U.S. Godzilla. Reaching North American shelves a month before Godzilla stormed onto screens, all eight of the Gamera films from 1965–80 are available courtesy of Mill Creek on two separate releases, presented in their original Japanese language soundtracks. Now people with little acquaintance with Gamera, outside of memories of watching the AIP television versions in the late ‘70s and the Mystery Science Theater 3000 riffing episodes, can witness all the full weirdness of this uniquely strange/wonderful/awful region of kaiju cinema.

This release will test many adults’ threshold for Japanese giant monster films. You’ll either devour the oddness and tolerate some of the poorer (actually, horrendous) installments, or you’ll check out before Gamera starts doing gymnastics routines while a children’s chorus sings the monster’s praises. Undiluted Gamera is simply not for everyone, although I can unreservedly recommend the five Mystery Science Theater 3000 episodes, which are available as a box set from Shout! Factory and should come as a packaged purchase with the Mill Creek Blu-rays. (The Mill Creek discs are inexpensive, so you really ought to shell out for the MST3K set as well.)

To provide some balance to all the Godzilla material I’ve written, and since I can never get enough of giant monsters, I spent two weeks running straight through the classic Gamera films on their Blu-ray discs — the first time I’ve watched the films in release order. I’ve returned with some of my sanity intact and a few observations on the individual films (I’ve written longer reviews of each elsewhere).

However, Gamera does require a bit of background first….

Gamera: A Brief History Full of Turtle Meat

Gamera: A Brief History Full of Turtle Meat

Gamera was born in 1965 when the giant monster boom in Japan was approaching its height. Although Toho Studios had dominated the genre since its inception in 1954 with Godzilla, the other three major studios threw out their own entries. Daiei Film Co. Ltd. took the genre the most seriously. They not only created the period-set Daimajin trilogy (filmed consecutively in 1965 and released in 1966), but they made a low budget imitation of the original Godzilla featuring a mega-turtle.

The inexpensive black-and-white Gamera: The Giant Monster emerged as an unexpected hit, and Daiei released a new film a year for the next six years until the company went bankrupt in 1971. Gamera came back with Daiei’s resurrection as New Daiei in 1980 with a low-cost cash grab, Gamera: Super Monster. The heroic turtle would not return until the astonishing trilogy of ‘90s “Heisei” films… but the newer movies are not the purview of this article. (Mill Creek has released the Heisei trilogy on Blu-ray as well.)

Although beginning as a Godzilla copy, the Gamera movies rapidly transformed into something different. Series director Noriaki Yuasa (who also worked on the special effects), producer Hidemasa Nagata (son of Daiei president Masaichi Nagata), and writer Nisan Takahashi found that Gamera appealed to young children and so steered the movies to speak directly to a young audience. From the fourth entry on, the filmmakers deliberately crafted the movies as “storybooks,” according to Yuasa. The Gamera films became bizarre children’s films, whose surreal monster action has given them cult likability that would later tap perfectly into the Mystery Science Theater 3000 mentality.

Gamera’s history in the U.S. has been strange. Only the first of the films reached stateside theaters. The next five went to TV via American International Pictures Television in fondly remembered dubs that showed in syndication through the early ‘80s. AIP didn’t pick up the seventh film, and around 1982 their rights dried up and Gamera — a staple of Saturday and Sunday afternoons — vanished in the U.S.

But in 1985, New York distributor Sandy Frank, who had pulled in huge money through altering the Japanese anime series Science Ninja Team Gatchaman into Battle of the Planets, picked up the rights to five of the Gamera films, including the seventh one AIP passed on, but excluding the fourth and the sixth. Sandy Frank gave the films new and hilarious dubs, and the movies showed sporadically on cable networks. They did not receive much attention until Mystery Science Theater 3000, at that time a local Minnesota show, secured the rights to use the Sandy Frank versions as riffing subjects. When Mystery Science Theater 3000 went national on Comedy Central, they re-did the Gamera films for Season 3, and the wild success of these episodes helped propel the show into a cultural phenomenon. It also gave Gamera back the spotlight, although the Sandy Frank dubs were unfamiliar to people who remembered the films back in the 1970s.

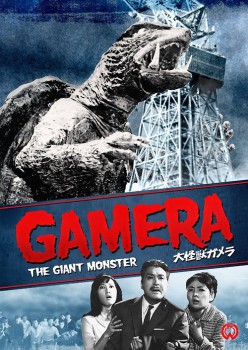

Gamera: The Giant Monster (1965)

Gamera: The Giant Monster (1965)

(Full review) Gamera started out as an eleven-years-late copy of the original Godzilla: a B&W film done in a dry, semi-documentary style about the appearance of a giant monster and the various attempts by scientists and the military to destroy it. It’s a bland picture that feels out of place among ‘60s Japanese science fiction, and the low budget means there’s little to enjoy from the special effects.

What the first movie does have in its favor are small touches of oddness that would become the focus of the later movies once director Yuasa and writer Takahashi figured out the niche: Gamera saving a child’s life and the bizarre idea of a monster able to spin itself through the air with sparkler legs. The child angle feels poorly thought out in this case, since rescuing little Toshio (the original “Kenny”) from a collapsing lighthouse is the only generous act Gamera commits during the film. Toshio dashing around, telling everyone that Gamera is good, is hilariously incongruous with the mass destruction the giant turtle continues causing.

This is the only classic-era Gamera film that received a theatrical release in the U.S., where it was edited with new footage of actors Brian Donlevy and Albert Dekker and titled Gammera the Invincible, with an extra “m” for pronunciation clarity. When Sandy Frank purchased the North American rights, the movie was released as Gamera without the U.S. footage or the bonus “m.” Shout! Factory gave the movie its current English title for a 2010 DVD release.

This is the only classic-era Gamera film that received a theatrical release in the U.S., where it was edited with new footage of actors Brian Donlevy and Albert Dekker and titled Gammera the Invincible, with an extra “m” for pronunciation clarity. When Sandy Frank purchased the North American rights, the movie was released as Gamera without the U.S. footage or the bonus “m.” Shout! Factory gave the movie its current English title for a 2010 DVD release.

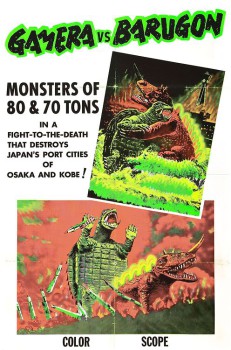

Gamera vs. Barugon (1966)

(Full review.) When Gamera: The Giant Monster proved a surprise success, Daiei Film upped the budget for the sequel, but also replaced director Noriaki Yuasa because the studio brass didn’t see him as A-list enough. Since this is the only movie of the series Yuasa did not direct, it is very telling that it’s such a bore. Although graced with a second and very odd monster—the freeze-tongue and rainbow ray-shooting lizard Barugon — most of the film is a slow chore about a group of men arranging to steal an opal from an island and then having a falling out over the consequences. The monster action is scarce, Gamera even scarcer and of no relevance to the rest of the plot, and clocking in at a hundred minutes (the longest of the series), the movie seems to take three days to watch. The series quickly dumped any pretense of aiming for adult viewers and returned Yuasa to the director’s chair.

For television release, AIP renamed the film War of the Monsters, a bland title that fits the movie’s overall tone.

Gamera vs. Gyaos (1967)

(Full review) The best of the classic Gamera series bridges nicely the attempts to make a serious monster film and Saturday-morning cartoonishness. A child is at the center, although not the main hero, and the adult characters have enough brains about them to make for legitimate drama when they try to stop the flying sonic-beam monster Gyaos. The tone is lightweight, but never flat-out ridiculous; it’s solid monster fun in tune with the times.

(Full review) The best of the classic Gamera series bridges nicely the attempts to make a serious monster film and Saturday-morning cartoonishness. A child is at the center, although not the main hero, and the adult characters have enough brains about them to make for legitimate drama when they try to stop the flying sonic-beam monster Gyaos. The tone is lightweight, but never flat-out ridiculous; it’s solid monster fun in tune with the times.

The special effects are plentiful, and even though a less expensive film than Gamera vs. Barugon, it feels far bigger in scale: full urban destruction scenes with Gyaos and plenty of use of Gamera as an opponent. The fights between the monsters are definitely the most exciting of the series. The silly stuff is still here (trying to stop Gyaos by trapping it on a rotating restaurant is a wonderfully daft concept), but the movie doesn’t seem to be attempting silliness for its own sake.

AIP released the film to television as Return of the Giant Monsters. The Sandy Frank version removed the “y” from Gyaos’s name, Gamera vs. Gaos.

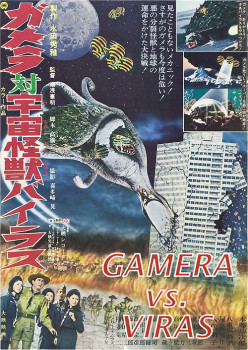

Gamera vs. Viras (1968)

(Full review) This is the first of the four Gamera films that follow the strict model of making two children — always one Japanese and one Caucasian — the heroes and putting the focus clearly on appeasing young viewers. This is when Yuasa’s structuring of the movies as storybooks kicks in. Gamera transforms completely into the “Friend of Children” and now has the famous “Gamera is really neat!” theme song. The movie also set in stone the pattern of Gamera getting incapacitated mid-movie, and then popping back for the finale.

Unfortunately, Gamera vs. Viras has fifteen minutes of stock footage from the three earlier films eating up its running time, which hampers an otherwise enjoyable children’s movie. The monster Viras, who only appears for the final battle, is a forgettable squid-thing with a parakeet face, and the least interesting of all Gamera’s opponents.

Unfortunately, Gamera vs. Viras has fifteen minutes of stock footage from the three earlier films eating up its running time, which hampers an otherwise enjoyable children’s movie. The monster Viras, who only appears for the final battle, is a forgettable squid-thing with a parakeet face, and the least interesting of all Gamera’s opponents.

Gamera vs. Viras was released to U.S. television as Destroy All Planets (AIP was trying to surf on the success of their release of Destroy All Monsters). For some reason, it was not part of the package of Sandy Frank films in the ‘80s, and thus never appeared on Mystery Science Theater 3000.

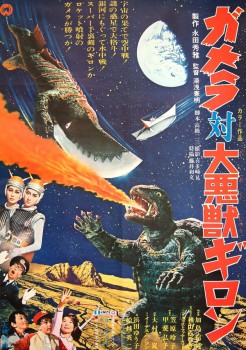

Gamera vs. Guiron (1969)

(Full review) Perhaps the most childlike of the movies, although that doesn’t count against it. Gamera vs. Guiron has almost no plot, but instead an extended situation: abducted aboard an automated spaceship to an empty base on the planet Tera, the two young heroes watch Gamera battle a giant letter-opener monster while they also try to avoid two alien women who want to eat their brains. That sums up the whole story. But it’s a flipped good time, playing for “weird” all it can and succeeding. Guiron is Gamera’s most memorable adversary, demonstrating enormous personality while sporting a ludicrous visual concept. All the sets are groovy ‘60s designs that play like “Take Your Son to Work Day” on the old Star Trek sets.

The AIP-TV version, Attack of the Monsters (what’s with these generic titles, AIP?), cut out a scene of Guiron hacking apart a “Space Gyaos” limb from limb and then making luncheon slices, apparently because it was too graphic. (It’s too funny for that.) The Sandy Frank version restored this scene, and Mystery Science Theater 3000 hopped on the weirdness train to make the best of their Gamera episodes.

Gamera vs. Jiger (1970)

(Full review) The second best of the Gamera movies shows a sudden maturity about how to handle these heroic children adventure tales. The two young heroes aren’t portrayed as pranksters, but responsible and smart, while the adults no longer look like utter dolts. The story has nice turns as well, with the children needing to pilot a miniature submarine into Gamera’s body to remove a larva that the evil monster Jiger planted there. Considering that the series seemed about ready to run out of ideas, Gamera vs. Jiger is willing to go to some new places and expand on the standard formula. The effects-work shows a pleasing uptick as well, featuring a return to scenes of urban destruction for the first time since Gamera vs. Gyaos.

Like Gamera vs. Viras, this film somehow didn’t end up in the Sandy Frank syndication package, which is a shame since Mystery Science Theater 3000 would have had a grand time with it. The only English version available is the AIP-TV release, titled Gamera vs. Monster X.

Gamera vs. Zigra (1971)

Gamera vs. Zigra (1971)

(Full review) Agony booth time! Daiei’s impending bankruptcy shows in every moment of this production, which feels depressingly cheap and aimed at an even younger crowd. The two heroes are now around seven or eight years old and they are annoying twerps who don’t deserve the spotlight — but then all the adults are even dumber. The scope of the special effects has been chopped down markedly, and the film feels cramped, stuck most of the running time in a shabby marine park. The monster scenes are bland and take place underwater on minimal sets, and what passes for “adventure” elsewhere is mostly a hapless alien agent running around an empty amusement park, trying to catch two kids who outwit her at every turn with moronic tricks. It’s hard to imagine even the youngest children managing to sit through this.

AIP-TV did not pick up the movie, and it was not seen in the U.S. until the Sandy Frank dub (which makes the movie almost unwatchable) appeared on cable in 1987. The Mystery Science Theater 3000 version does the movie proud however: it’s the ideal kind of “bad” for them.

Gamera: Super Monster (1980)

(Full review) This is nothing more than a clip show. New Daiei wanted to raise some fast money, so they convinced Noriaki Yuasa to make a film that could recycle the fight scenes from the other Gamera movies with a minimal amount of new footage to create something like a story. Yuasa wasn’t thrilled with this surgery he had to perform on the monster he created, but he did as well as could be expected, given the modest aims and a budget no larger than a half-hour television drama. The new story has three alien women who are hiding on Earth confront a space pirate who sends a series of monsters to conquer the planet. All the monsters are from the previous films and Gamera bests them one at a time in rehashed footage. Only about two minutes total of new VFX of Gamera appear.

This film may have interest for young children who have not seen the other Gamera films, but otherwise only die-hard kaiju completists need apply.

Series ranking

Series ranking

From best to worst, my ranking of the classic Gamera series:

- Gamera vs. Gyaos

- Gamera vs. Jiger

- Gamera vs. Guiron

- Gamera vs. Viras

- Gamera: The Giant Monster

- Gamera vs. Barugon

- Gamera vs. Zigra / Gamera: Super Monster

I had to give a tie for last place: Gamera: Super Monster is marginally a better story, but its clip-show status knocks it down a notch

The Mill Creek Blu-rays

Mill Creek’s Blu-rays are presented over two volumes, with four films squeezed onto each of the two discs. This causes some compression issues, although it only bothered me noticeably on the black-and-white Gamera: The Giant Monster. The films are in their original 2.39 aspect ratios (except for Gamera: Super Monster, which was shot 1.85) with mono Japanese soundtracks. The picture quality won’t please Blu-ray hardcores, but the films look better than they ever have on video. There are no extras and not even a menu, aside from selecting which of the films you wish to watch.

There is one serious problem with the Mill Creek release: no English versions or language option. Although I personally have no interest in watching English dubs—unless there is a man and two robots also watching—these movies are aimed primarily at children, and dubbed versions would make it easier to share with the target audience. The Shout! Factory DVDs all contain the English versions as well, so if you have children you might want to invest in those instead. These Blu-rays are strictly for older kaiju fans.

Ryan Harvey is one of the original bloggers for Black Gate, starting in 2008. He received the Writers of the Future Award for his short story “An Acolyte of Black Spires,” and his stories “The Sorrowless Thief” and “Stand at Dubun-Geb” are available in Black Gate online fiction. A further Ahn-Tarqa adventure, “Farewell to Tyrn”, is currently available as an e-book. Ryan lives in Costa Mesa, California where he works as a professional writer for a marketing company. Occasionally, people ask him to talk about Edgar Rice Burroughs or Godzilla in interviews.

Wow! My definition of a great country is one where the entire Gamera saga is available to households with even a modest income.