Speculative Fringe: God is an Iron at the Montreal Fringe

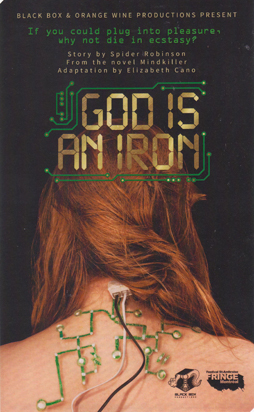

Monday, June 16, I went to see a show at the Montreal Fringe Festival. Local theatre company Black Box Productions was staging their adaptation of God is an Iron, originally a short story by Spider Robinson. The story, first published in 1979, was later expanded by Robinson into a novel called Mindkiller (which I have not read). The play, adapted by producer and Black Box chief Elizabeth Cano, sticks close to the original story, finding a solid stage-worthy drama in the sf tale. The play has two more performances — on Saturday and Sunday, full details here — and there are plans afoot for a filmed version to be available later.

Monday, June 16, I went to see a show at the Montreal Fringe Festival. Local theatre company Black Box Productions was staging their adaptation of God is an Iron, originally a short story by Spider Robinson. The story, first published in 1979, was later expanded by Robinson into a novel called Mindkiller (which I have not read). The play, adapted by producer and Black Box chief Elizabeth Cano, sticks close to the original story, finding a solid stage-worthy drama in the sf tale. The play has two more performances — on Saturday and Sunday, full details here — and there are plans afoot for a filmed version to be available later.

In the near future, a young man, Joe, enters an apartment and finds a woman, Karen, near death. She’s plugged into a machine stimulating the pleasure centre of her brain, an addictive high common in this future, and one that often leads to death as the addict comes to prefer the ongoing pleasure to food or drink. Joe gets Karen out of the machine and tries to lead her back to health. Who is she? Why did she plug herself into pleasure, knowing it could lead to her own death? Who is he, and why does he care? The set-up gives us questions, and over the course of the story we come to find out the answers. Some are profound, and the last is almost a punch-line: like a punch-line, it collapses all the pathos of the story and the themes into a sudden and surprising realisation.

The tale’s a meditation on empathy and pleasure; more precisely, on empathy and hedonism. Living for pleasure is self-directed. So what drives us — as human beings seem to be driven — to be social animals? Is there some merit to living for others beyond pleasure? Cano’s script, a faithful adaptation of the story using much of the original text, tries to probe these questions.

The set’s fairly simple: a bed, chairs, a desk, and a large video display. The screen’s used well throughout the performance, displaying information from Karen’s computer as Joe tries to understand who she is, and later presenting a key video phone call. A third actor, James Murray, plays two separate roles on-screen; the effect feels natural, and the video material feels well-integrated into the action of the play.

The set’s fairly simple: a bed, chairs, a desk, and a large video display. The screen’s used well throughout the performance, displaying information from Karen’s computer as Joe tries to understand who she is, and later presenting a key video phone call. A third actor, James Murray, plays two separate roles on-screen; the effect feels natural, and the video material feels well-integrated into the action of the play.

Tali Brady, as Karen, gives a particularly strong performance. She delivers emotionally intense material with a sense of naturalism, and I think her performance helps us to gradually understand her character as the story goes on. Brendan Walker, as Joe, has the harder task of carrying the opening minutes of the play almost on his own; he comes into his own with a final monologue, delivered by a character very slightly drunk — a good decision by Cano to give the original story’s extended pseudo-philosophical musings on pleasure and human biological wiring something a little more grounded in character.

The adaptation is on the whole extremely faithful to the story, with some well-handled bits of exposition added about the near-future technology. At the same time, the original tale’s structured to make sense as a short story, not as drama. So the stage version risks turning into dueling monologues. On the whole, the play manages to avoid that, thanks in part to the fact that we remain in suspense about the motives and nature of at least one character until the end.

Still, the play does have to work through a considerable amount of material in its fairly brief running time (under an hour). It inherits a good balance of humour and emotional weight from the original text, but also works out how to stage them effectively. Particularly effective is the way that the science-fictional ideas of the source text are brought out: they drive the story, establish the theme, and also help create a distinctive setting.

Still, the play does have to work through a considerable amount of material in its fairly brief running time (under an hour). It inherits a good balance of humour and emotional weight from the original text, but also works out how to stage them effectively. Particularly effective is the way that the science-fictional ideas of the source text are brought out: they drive the story, establish the theme, and also help create a distinctive setting.

There are two more showings scheduled for God is an Iron at the Montreal Fringe, but Cano told me she hopes to tour with it across Canadian Fringe Festivals next year, hopefully reaching Toronto, Winnipeg, Saskatoon, Edmonton, Vancouver, and Victoria, before ending at the Spokane Worldcon. She also plans a filmed version of the play, to be funded through Kickstarter and recorded after the present run, and which will be available for sale.

God is an Iron is Cano’s third theatrical sf adaptation through her Black Box Productions company. The first, Shades of Grey, played with episodes of the original Twilight Zone; the second was Arthur C. Clarke’s How We Went to Mars. “Black Box does speculative fiction theatre, that’s what we do,” Cano said. She has a number of projects in mind for the future, mentioning Heinlein, Asimov, Robinson and others as rich veins of source material, but is focusing on this show for now. ‘Robinson’s my favourite living author,” she said. “He accepts the ‘living’ proviso, because my favourite writer is Heinlein” — one of Robinson’s favourites as well.

Cano doesn’t hide the fact that God is an Iron is a deeply personal project for her. Not only because of her respect for Robinson, but because of the subjects of the play. There’s a reason a page of the program contains contact information for local crisis centres and hotlines. Much as the play deals with science-fictional themes, it’s also socially-aware theatre. After the show I saw a man come up to Cano and express his appreciation for the play’s grappling with addiction and suicide. They spoke for a minute; as he left she reflected: “That’s the reaction I was hoping for! That’s why I did this play.”

Cano doesn’t hide the fact that God is an Iron is a deeply personal project for her. Not only because of her respect for Robinson, but because of the subjects of the play. There’s a reason a page of the program contains contact information for local crisis centres and hotlines. Much as the play deals with science-fictional themes, it’s also socially-aware theatre. After the show I saw a man come up to Cano and express his appreciation for the play’s grappling with addiction and suicide. They spoke for a minute; as he left she reflected: “That’s the reaction I was hoping for! That’s why I did this play.”

God is an Iron is effective low-budget theatre — and effective low-budget science-fiction theatre. It does what science fiction does well, building a human story around an idea of the future. It’s also remarkably faithful to its source material, with much of the text of the story turning up in dialogue or an opening voice-over. It’s a must-see for Spider Robinson fans, but more than that, it’s solid work worth seeing for the way an established sf story’s translated to a new medium.

Matthew David Surridge is the author of “The Word of Azrael,” from Black Gate 14. His ongoing web serial is The Fell Gard Codices. You can find him on Facebook, or follow his Twitter account, Fell_Gard.

[…] Matthew David Surridge outlines the basic story in his Black Gate review of the 2014 Montreal production: […]