Visiting York Castle

York in northern England is justifiably famous for its well-preserved Viking city. The foundations of an entire Viking neighborhood are preserved under glass at the Jorvik Viking Center, a delightfully cheesy tourist trap that includes an animatronic Viking taking a dump in a Norse outhouse.

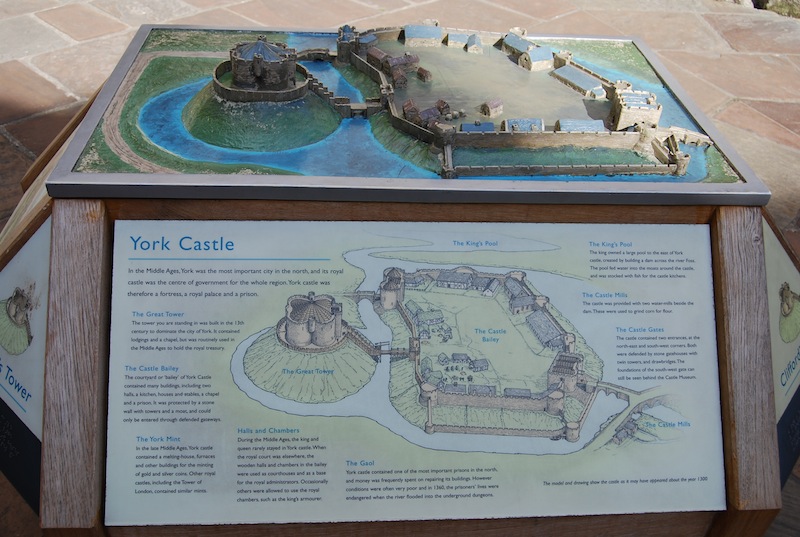

But let’s not dwell on that. For a different, yet equally one-of-a-kind sight, check out York Castle just a short stroll away. It was founded in 1068 by William the Conqueror as a typical motte and bailey castle. These fortifications included an artificial mound (the motte) with a wooden tower and wall on top, and another enclosed area (the bailey) in front of the base. The Normans slapped these forts together wherever they conquered because they were cheap and quick to build. It’s said they finished York Castle in just eight days!

The Normans needed to hurry. Almost as soon as it was finished, York Castle was besieged by rebellious locals. The Normans fought them off, but felt the need to build a second motte and bailey castle in town. Despite York now being protected by two castles, it fell to another rebellion that had aligned itself with a Viking invasion that same year.

What followed has gone down in history as the Harrying of the North. The Normans scoured the land with a vengeance, kicking out the invaders and slaughtering much of the local population. With York being one of the most important towns in the north, the Normans soon set about improving York Castle, adding a moat and an artificial lake to impede any approach.

York grew in population and wealth and numerous kings improved upon the castle. Sad to say, it was the site of one of the blacker days in Yorkshire history. In 1190, the local Jewish population, fleeing a pogrom, locked themselves inside the castle. The local constable stayed with them for a time and then went out to reason with the mob. The Jews, fearing treachery, wouldn’t let him back in.

A siege began, and when it looked like the castle would fall, the Jews set it on fire and killed themselves. Only a few came out and surrendered. They were put to death, even though they promised to convert to Christianity. A total of about 150 Jews died.

When I went on a local ghost tour, I was told that, according to legend, on the anniversary of the massacre the walls glow blood red at night. One hopes this is an actual legend. It would be distasteful to make something like this up to wow the tourists. On the other hand, folklore has a way of operating in reverse, with invented legends becoming “real” ones! The walls do indeed have a reddish tinge, but that’s due to a seventeenth century explosion. The existing stone walls hadn’t even been built in 1190.

York Castle was one of many fortifications that could be used to defend the country against a Scottish invasion. King Henry III, fearing such an invasion, ordered York Castle rebuilt in stone. The main tower was constructed to an unusual design. It has a quatrefoil plan, with four main lobes penetrated by arrow slits, later turned into gunports. As you can see from the photos, there are rounded towers between each of the lobes.

There is no other castle like this in England. It’s thought that it was made this way in order to give more overlapping fields of fire for the defenders. Apparently, castle designers decided that it didn’t provide enough extra defense for the increased complexity of construction, because the experiment was never repeated.

This strengthening of York Castle led to the abandonment of York’s second castle, of which only the original motte now remains.

York Castle continued being important throughout the Middle Ages, acting as a base for kings fighting in the north and also as a royal mint. Like many castles, it was used to hold important prisoners, including many Templars when their order was dissolved in 1307, and in the seventeenth century George Fox, founder of the Society of Friends (the Quakers).

York Castle survived a battle in the English Civil War, quarrying for stone, erosion, and an explosion in 1684 that gutted the building. Yet it still stands. If you clamber up the stairs to the castle, you’ll be rewarded with sweeping views of York, as well as a good look at a rare castle design.

Sean McLachlan is a freelance travel and history writer. He is the author of the historical fantasy novel A Fine Likeness, set in Civil War Missouri, and the post-apocalyptic thriller Radio Hope. His historical fantasy novella The Quintessence of Absence, was published by Black Gate. Find out more about him on his blog and Amazon author’s page.

All photos copyright Sean McLachlan.