Ancient Worlds: Talking to Yourself Again?

When the Argonauts land in Colchis, Jason makes a novel suggestion.

When the Argonauts land in Colchis, Jason makes a novel suggestion.

“Hey guys! Let’s, like, NOT storm the castle and steal what we want. Let’s go up, ring the doorbell, and ask politely! What’s the worst that could happen?”

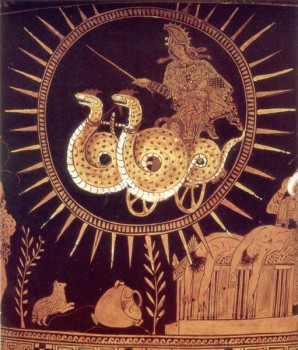

To which King Aeetes responds, “Golden Fleece? Sure you can have it! All you have to do is plow a field with a plow pulled by fire breathing oxen, plant a few acres with dragon’s teeth, wait til those dragon’s teeth turn into fully grown armed men, and then kill them all before they get you. Do it myself all the time.”

It’s a folklore classic: the impossible task. Our hero gets the prize of his dreams (princess, kingdom, unimaginable wealth, golden fleece) as soon as he does something that no human being can possibly do. And then s/he does it.

Usually with help. And this time, that help will come not from the other Argonauts, but from Aeetes’s daughter. As you remember from last time, Athena and Hera have arranged for Eros to make Medea fall in love with Jason and at their first meeting, he’s in the front row. The princess is shot with one of the infamous arrows and immediately falls in love with our young adventurer.

She also already knows he is doomed. She goes back to her room, dreams about doing all these tasks herself, wakes up, and invents a new literary device.

I am referring to the Internal Monologue.

It’s strange to think about literature without internal monologues. They’re a critical component of storytelling today. Well utilized, they can flip an entire story on a dime.

Try imagining The Dresden Files without Harry’s running commentary.

Imagine what Harry Potter could have looked like if we’d had a single internal monologue from Snape.

They’re central to the way we think of characterization. Entire books can hinge on them, especially in genres that are highly dependent on character motivation as opposed to action. (Think espionage, political dramas, romance…) But prior to this work we have no existing examples of them, not in this fully fleshed out form.

We get brief nods to the idea in The Odyssey: we repeatedly hear Odysseus ponder how he will kill all of Penelope’s suitors and get away with it. But they are brief deliberations, never more than four or five lines. This is an extended deliberation on Medea’s part. She has one hell of a dilemma: she’s fallen in love with a complete stranger, who has four of her nephews with him. It’s his fate (and her sister’s sons) against that of her father.

So Apollonius chooses to let us feel the weight of that decision. This is one of the places that his strength as an author really shines: he is sensitive to the real emotion in her internal debate.

In the end she nearly opts for suicide, but when she reaches into her box of poisons she draws out instead a bottle that will make Jason capable of performing the tasks he is set. Her decision made, she arranges a meeting with the visiting prince, and history is made.

So the next time your favorite heroine shares the ins and outs of her next decision with you, or the next time you watch the original release of “Blade Runner” and you’re irritated by the voice-over they made Harrison Ford do, remember Medea.