The Public Life of Sherlock Holmes: Eille Norwood: the Silent Detective

This may shock you, but there were on-screen Sherlock Holmes before Benedict Cumberbatch! And for you old-time fans, even before Robert Downey Jr. Really! The first great movie Holmes comes from the silent film era. And he shared a last name with another actor who would give arguably the greatest portrayal of the world’s first private consulting detective.

William Gillette had come to personify Sherlock Holmes through repeated performances of his stage play in the U.S. and Europe. His 1916 film version certainly helped as well, but was not a critical part of his success. Anthony Edward Brett would become the first great movie Holmes, though he would achieve it as Eille Norwood.

Born in 1861, Norwood was primarily a stage actor in England when he landed the role that would make him famous throughout the U.K..

In 1921, a British film company named Stoll decided to film a series of shorts based on Doyle’s stories. For the next two years, they would produce forty-five of the twenty-minute films, along with two longer ones. Doyle’s short stories fit the twenty-minute length quite well and Stoll wasn’t forced to add inauthentic filler to them.

The first fifteen, chosen randomly from among Doyle’s stories, were called The Adventures of Sherlock Holmes. That same year, the first version of what would be the most famous film title in the Canon was made, The Hound of the Baskervilles. Maurice Elvey directed all sixteen films. That same year, Elvey made a romantic drama called The Fruitful Vine. The lead was played by a young man named Basil Rathbone. How about that?

The following year, Stoll made fifteen more Norwood/Willis titles and called them The Further Adventures of Sherlock Holmes. George Ridgewell moved in to replace Elvey as director.

In 1923, Norwood, Willis, and Ridgewell worked together on fifteen more shorts, The Last Adventures of Sherlock Holmes. After completion of them, Maurice Elvey would return from the United States to make a feature length version of The Sign of Four. For this final Stoll Holmes film, Hubert Willis was replaced by Arthur Cullin.

In 1923, Norwood, Willis, and Ridgewell worked together on fifteen more shorts, The Last Adventures of Sherlock Holmes. After completion of them, Maurice Elvey would return from the United States to make a feature length version of The Sign of Four. For this final Stoll Holmes film, Hubert Willis was replaced by Arthur Cullin.

The films were set in the 1920s, which bothered Doyle. He said “My only criticism of the films is that they introduce telephones, motor cars, and other luxuries of which the Victorian Holmes never dreamed of.” The sentiment is understood, but Watson drove Holmes in “a small car” to his meeting with the German spy Von Bork in “His Last Bow.”

Holmes certainly would have used whatever available technology would assist him, albeit grudgingly. Stoll presented an Edwardian Holmes, rather than a Victorian one. Not a huge difference. But it started the trend of modernizing Holmes, which was certainly a feature of Rathbone’s Universal pictures.

Norwood was fifty-nine when he first appeared as the master detective. Sir Arthur was quite impressed with Norwood’s appearance: “His wonderful impersonation of Holmes has amazed me.” He was also pleased with the quality of the Stoll productions and worked to ensure that they had rights to all of his stories.

Norwood was fifty-nine when he first appeared as the master detective. Sir Arthur was quite impressed with Norwood’s appearance: “His wonderful impersonation of Holmes has amazed me.” He was also pleased with the quality of the Stoll productions and worked to ensure that they had rights to all of his stories.

Norwood had very definite ideas about how to portray Holmes. He said: “My idea of Holmes is that he is absolutely quiet. Nothing ruffles him but he is a man who intuitively seizes on points without revealing that he has done so, and nurses them up with complete inaction until the moment he is called upon to exercise his wonderful detective powers. Then he is like a cat – the person he is after is the only person in all the world, and he is oblivious of everything else until his quarry is run to earth.”

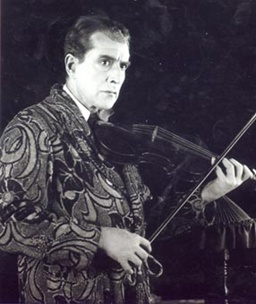

Wow! That is a pretty accurate description. He was so determined to be an authentic Holmes that he taught himself the fingering of a violin, which is no simple task. He is only one of many screen Holmes to credit the great illustrator, Sidney Paget, with serving as a great influence on his depiction of the role.

Later reports state that Elvey and Norwood disagreed about the proper interpretation. Allegedly Norwood suggested they film it his way first, then redo the shot in Elvey’s fashion. This was done, then both men watched the results the next day. Elvey admitted that Norwood had the proper perspective on the role.

Fans of Doyle’s stage play for The Speckled Band (a prior column) may recognize a similarity to a disagreement between the author and actor Lyn Harding, who was playing Dr. Grimesby Roylott.

Norwood made one of my favorite quotes about Sherlock Holmes: “The last thing in the world that Holmes looks like is a detective. There is nothing of the hawk-eyed sleuth about him. His powers of observation are but the servants of his powers of deduction, which enable him, as it were, to see round corners, and cause him incidentally to be constantly amused at the blindness of his faithful Watson, who is never able to understand his methods.”

It is said that his greatest strength was his ability to dress in disguise, which happened frequently in the Canon. With makeup and wigs, he could completely transform himself and be unrecognizable. But it was reported he could also make subtle changes that had significant impacts.

By only changing his hairstyle and cutting his eyebrows, he appeared as Holmes before director Maurice Elvey. Elvey knew Norwood was his man. It was Elvey who recommended the actor to Stoll for the role.

By only changing his hairstyle and cutting his eyebrows, he appeared as Holmes before director Maurice Elvey. Elvey knew Norwood was his man. It was Elvey who recommended the actor to Stoll for the role.

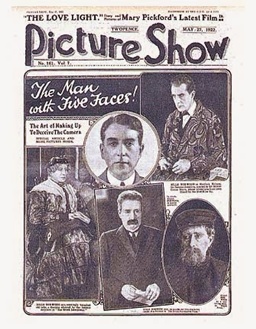

Norwood regularly appeared in disguise throughout the films. In 1924, The Picture Show magazine featured this talent, saying “…that when he dons a wig or faked eyebrows they look as though they belong to him, and not as the camera often makes such things appear – more false even than they are.”

The first script in the series called for a scene with Holmes wearing a white beard. Norwood felt it was completely wrong and told Jeffrey Bernard, Stoll’s head of productions, that they didn’t have a proper understanding of Holmes.

One can only imagine that Bernard felt he was dealing with a temperamental actor and he told Norwood that he would never be able to convincingly change his height and appearance.

The fine actor took up the gauntlet. The very next day, a taxi driver was standing on the studio set, where visitors were not allowed. Bernard sent an employee to remove the driver, who argued vehemently in a Cockney accent and refused to budge.

After arguing for several more minutes, the little man rose up to his full height and revealed he was Eille Norwood. Norwood would continue to amaze through the entire series.

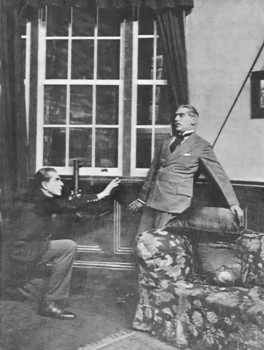

Remember that Norwood was playing a brilliant, cerebral detective in silent films. I cannot imagine a more difficult acting task.

Remember that Norwood was playing a brilliant, cerebral detective in silent films. I cannot imagine a more difficult acting task.

He used his actions and subtle movements to create an image of deliberation. Imagine Jeremy Brett’s fantastic portrayal, but with no words.

Norwood appeared on movie screens more than any other Holmes actor. Likewise, Hubert Willis holds the record of Dr. Watson portrayals in film.

Sadly, very few of Norwood’s films are available, which is true of so many silent films. However, while I no longer have the email from the British Film Institute, I was informed by the BFI that they have all (or perhaps it was nearly all) of Norwood’s films on safety stock. Which I believe means they are preserved but not in a format to be made commercially available (at present).

Norwood’s legacy has died out for all except those Holmesians interested in the early portrayals of the world’s first private consulting detective. We have just a few movies and the words of contemporary writers and historians through the years. Interestingly, noted Holmes film experts have differing opinions. Michael Pointer considers The Hound to be the best production of the bunch. David Stuart Davies referred to it as “ a stodgy and lack-luster production.”

Just because Stoll was finished with Sherlock Holmes did not mean Eille Norwood was. A stage play was written by J.E. Harold Terry and Arthur Rose and called The Return of Sherlock Holmes.

Just because Stoll was finished with Sherlock Holmes did not mean Eille Norwood was. A stage play was written by J.E. Harold Terry and Arthur Rose and called The Return of Sherlock Holmes.

It came as no surprise that the screen star was cast in the title role. Story lines were borrowed from “Charles Augustus Milverton”, “The Disappearance of Lady Frances Carfax”, “The Red-Headed League” and “The Empty House”. The plot and story development resembled William Gillette’s play.

The female lead in Gillette’s play, Alice Faulkner is replaced by Lady Frances Carfax, who is being swindled and poisoned by the Schlessingers (not the Larrabees). Moriarty is dead, but his role is played by Col. Moran. Norwood escapes from the famous “Gillette Gas Chamber” as well.

Moran takes a shot at Holmes from Camden House across the street and is finally fooled by a wax bust and captured inside 221B Baker Street. Sounds familiar, doesn’t it?

The Stage said that Norwood “carried off the honors of the evening on Tuesday with his admiral acting, as well as his skillful production work.”

The Daily Telegraph used such phrases as “the perfect exquisiteness of this play” and that the audience hung “upon it in a fascinated silence like a birds the charming serpent draws.” They ended the review by stating that “Mr. Eille Norwood moves grandly and gloomily through the part of Holmes, and is wildly applauded at the end of each act.”

The play was so successful it was taken to Holland and Denmark, where Henri De Vries and Herman Florents replaced Norwood.

Other actors would play Sherlock Holmes in the 1920s on the silver screen, but none would approach the popularity in the role achieved by Eille Norwood. He must rank as one of the great Holmes.

Bob Byrne founded www.SolarPons.com, the only website dedicated to the ‘Sherlock Holmes of Praed Street’ and blogs about Holmes and other mystery matters at Almost Holmes.

For over a decade, he ran HolmesOnScreen.com, the Net’s leading resource for Holmes in film and on television.

[…] For Monday, May 13, we look at silent Holmes star Eille Norwood over at Black Gate. […]

[…] So, back in May, I posted about Eille Norwood for The Public Life of Sherlock Holmes. Curiously, that post was the third most popular post for all of Black Gate in July. I haven’t got a clue. […]

[…] Back in May, I wrote about Eille Norwood’s turn as the silent film era’s finest Holmes. Now, just about any discussion concerning who the greatest actor of the silent era was will involve the name John Barrymore, who was known as “The Great Profile.” […]

[…] his turn-of-the century stage play, William Gillette was the first great Sherlock Holmes. Eille Norwood was the second, making a series of popular silent film adaptations of Doyle’s stories in the early twenties. The […]