Ancient Worlds: What Kind Of Book Is This, Anyway?

We all know the old adage “Never judge a book by its cover.” But when it comes to literal application, we all do. That’s because our book culture encourages it. The cover won’t always tell us much about the quality of a book, true, but if we want to know what kind of book it is, the cover is where we find out.

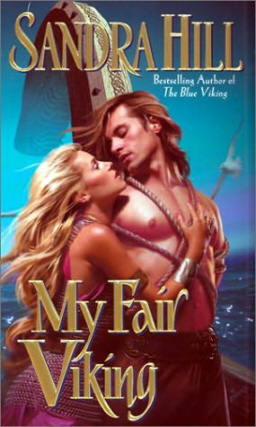

Shirtless guy holding woman in historically inaccurate clothing in highly improbable position? Romance.

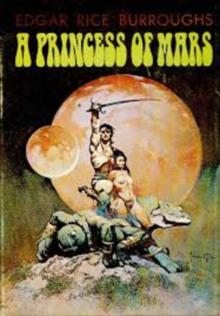

Shirtless guy flexing while holding sword (with or without scantily clad woman clinging to his knees)? Heroic fantasy.

Woman scantily clad while still wearing a lot of black leather with a sword, possibly straddling a motorcycle? Urban fantasy. Probably.

Genre is how the publisher knows what kind of cover to put on a book. It’s also how the reader knows, more or less, what to expect when they pick a novel up. If you buy a book with a silhouette of a tank on the cover and get a story that is 90% romance, you’re going to be perplexed.

The same was true of ancient books, although the cues were given in different ways.

Heroic fantasy (AKA epic poetry) came in dactylic hexameter and covered serious, manly topics. Love poetry came in elegiac couplets. Romance novels were written in prose. And just as with modern literature, ancient readers had expectations of the contents and topics of a work based on its genre. Those rules could be played with, definitely, but push them too far and you could get lost in the weeds.

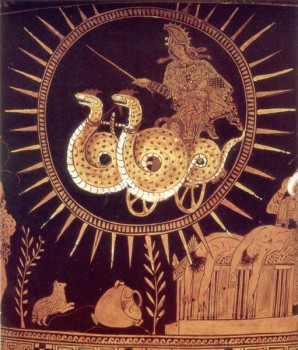

So imagine the perplexity of the Ancient Reader when they got to the opening of the Argonautica’s Book 3 and found an invocation to the Muse of erotic poetry. (Uh, that’s ‘poetry having to do with love,’ not ‘limericks you wouldn’t want your mother to catch you reading.’)

This is roughly the ancient equivalent of getting to page 300 in a Clancy novel to discover him wrapping up a thorough analysis of the tactical differences between tank maneuvers in the Battle of the Bulge and the first Gulf War… and then launching into a sonnet.

So why do it? There’s a lot of debate on this, but I think a safe answer is that Apollonius is, for better or worse, playing with the idea of genre here. Jason is already not a typical epic hero: he isn’t the bravest, strongest, or the best fighter. But he is charming. He is a diplomat, a hero who works either through his own persuasion or through his allies. Apollonius is trying to turn these into heroic attributes.

This is also the age of the novel. The Argonautica was written when romantic fiction had become very popular. You could argue that Apollonius is trying to “update” the epic for Hellenistic tastes.

The Argonautica also has a gender problem. (Get it? Gender, genre… it’s a joke… in, uh, French… MOVING RIGHT ALONG.) The real hero of the piece, as we will see shortly, is Medea. She’s the one who will actually do the work required to get the Golden Fleece. She’s arguably the most interesting character in the entire work and definitely among the most powerful. But she’s a woman.

That’s less of a problem for Apollonius than it was for, say, Homer. As I will talk about next week, Jason can share the stage with Medea. But like Circe (fun fact: who is Medea’s aunt), it won’t be entirely of her own free will.

I’ve often said that we are currently in a “Hellenistic Period” when it comes to art and literature. We enjoy playing with genre, we like reboots and recapitulations, variations on theme, and breaking the fourth wall. Sometimes it works, sometimes it doesn’t. Whether or not Apollonius’s experimentation works is a matter of taste, but it is telling that he is getting more attention now from academic writers than he has for over a century.

I’ve often said that we are currently in a “Hellenistic Period” when it comes to art and literature.

Hadn’t thought of it that way, but it does fit nicely.

Somebody ought to start a terrible band called Medea and the Golden Carpool, but it won’t be me.

Jason and the Argonauts is a fairy tale — the fairy tale type known as “The Girl Helps the Hero Flee.”

Followed, as it often is, by the type known as “The Forsaken Fiancee.” Alas, for once that one ends unhappily.

The :story: of Jason and the Argonauts is a series of folk tales, yes, but not really a fairy tale in the sense we mean it. And I have to confess to being pretty hostile to narrative typology. It’s useful for cataloging but otherwise does more harm than good.

But The Argonautica isn’t a fairy tale, or a folk tale. It’s a deliberate work of Art. Which is a small but, in this case, I think important distinction.