The Attenuated Hero: Vicious by V.E. Schwab

V.E. Schwab had written a number of YA novels when, in 2013, Tor published her book Vicious. Billed by some as a super-hero story, it had elements of that genre while also, to some extent, questioning its assumptions. Reading it, I found that the book seemed interested in questions of morality, heroism, and villainy, but that the super-hero aspects were so attenuated I doubt it would have occurred to me to consider it as a super-hero story without the claims of the book jacket. Its handling of ideas of heroism felt like a reiteration of themes comics (Marvel, DC, and independent) have been interrogating relentlessly (if not neurotically) for at least thirty years. In some ways, it’s best to simply ignore the ‘super-hero’ tag. If you do, you’re left with a well-paced and sharply-structured novel. And on its own terms, it’s an enjoyable tale.

V.E. Schwab had written a number of YA novels when, in 2013, Tor published her book Vicious. Billed by some as a super-hero story, it had elements of that genre while also, to some extent, questioning its assumptions. Reading it, I found that the book seemed interested in questions of morality, heroism, and villainy, but that the super-hero aspects were so attenuated I doubt it would have occurred to me to consider it as a super-hero story without the claims of the book jacket. Its handling of ideas of heroism felt like a reiteration of themes comics (Marvel, DC, and independent) have been interrogating relentlessly (if not neurotically) for at least thirty years. In some ways, it’s best to simply ignore the ‘super-hero’ tag. If you do, you’re left with a well-paced and sharply-structured novel. And on its own terms, it’s an enjoyable tale.

The book alternates between present-day scenes and flashbacks, and a large part of the success of the novel rests in the fact that Schwab successfully pulls off this technical trick without blunting her momentum. Ten years ago, Victor Vale and Eli Cardale (later Eli Ever) are brilliant pre-med students who discover that near-death experiences can, under certain circumstances, grant survivors strange powers. They experiment, things go wrong, and while they both get powers, they end up as enemies. Now, in the present, Victor’s gotten out of prison, recruited some assistants, and is seeking out Eli — who himself has been up to some surprising things in the previous years, having come to hate the extraordinary people (or EOs) gifted with powers.

Schwab’s prose is fine. Relatively simple — the novel seems aimed at the emerging field of New-adult books — it’s correspondingly clear, and moves like a shot. Descriptions are minimal and word choice unsurprising, but it focuses on character without slowing the action. The storytelling’s strong, then. But the plot’s fairly minimal and tends to rely on coincidence: characters who happen to have just the right powers to shape the story turn up in the right places at the right time or happen to have the right relation to each other. One character takes frequent lucky breaks as an indication that God’s helping him; thematically I can find nothing to support that, but if you replace ‘God’ with ‘the author’, it seems apt.

Schwab’s prose is fine. Relatively simple — the novel seems aimed at the emerging field of New-adult books — it’s correspondingly clear, and moves like a shot. Descriptions are minimal and word choice unsurprising, but it focuses on character without slowing the action. The storytelling’s strong, then. But the plot’s fairly minimal and tends to rely on coincidence: characters who happen to have just the right powers to shape the story turn up in the right places at the right time or happen to have the right relation to each other. One character takes frequent lucky breaks as an indication that God’s helping him; thematically I can find nothing to support that, but if you replace ‘God’ with ‘the author’, it seems apt.

On the other hand, the structure of the plot, the way Schwab parcels out bits of story, is excellent. The flashbacks never slow the story, but contrast nicely with the present-day scenes. As the book goes on, the present-day chapters grow longer and meatier, while the flashbacks broaden to include more characters more often. The result’s a fine slow build to a climax made more meaningful by our grasp of the pasts and motivations of the various figures involved.

The characters aren’t terribly deep in and of themselves, in that their internal monologues aren’t suprising or complex. They’re archetypes, for the most part — the troubled young teen girl, the big smart guy nobody realises is smart, the religiously-motivated killer, the mean-girl siren — but Victor, the main character, has enough individuality to stand out. He’s emotionally distant, but creates a distinctive kind of art by defacing self-help books written by his parents. He’s interesting enough to sustain the novel, and unpredictable enough to be both hero and anti-hero or, if you prefer, villain.

Which dichotomy actually brings up the main weak point of the book. It seems to want to investigate questions of heroism, villainy, and the difference between the two, but the actual plot doesn’t allow that investigation to go particularly deep. Eli wants to cast himself as a hero, but we know too much to be fooled for a moment and never really become convinced enough of his point of view to ever share his sense of himself. So the undercutting of his ‘heroism’ is far too obvious. Victor describes himself as a villain, and sometimes does villainous things, but nothing so bad that he forfeits all claim to sympathy; structurally he’s the hero, and the story doesn’t challenge that in any meaningful way.

Which dichotomy actually brings up the main weak point of the book. It seems to want to investigate questions of heroism, villainy, and the difference between the two, but the actual plot doesn’t allow that investigation to go particularly deep. Eli wants to cast himself as a hero, but we know too much to be fooled for a moment and never really become convinced enough of his point of view to ever share his sense of himself. So the undercutting of his ‘heroism’ is far too obvious. Victor describes himself as a villain, and sometimes does villainous things, but nothing so bad that he forfeits all claim to sympathy; structurally he’s the hero, and the story doesn’t challenge that in any meaningful way.

The book suggests that the near-death experiences which result in super-powers also take something away from the people who suffer them — that they lose some aspect of their personality, that their sense of morality changes or is lessened. It’s an intriguing idea, not least because it suggests that Eli’s perspective on the EOs is accurate. But we don’t get a specific sense of what happens to the EOs and Victor’s allies seem entirely too nice to really be credible villains. For the book to be about villains struggling against villains, it would have to have been darker; for it to convey the sense of the EOs as villainous or broken, it would have to have been more explicit in showing how that affected their thoughts and behaviour.

What the book gives us is a story about people with powers but without any highly-developed sense of morality, which is entertaining enough but not particularly new. It’s certainly nothing new for comics or super-hero stories. Of course, the fact that the two leads are brilliant young men who meet at university, one of them named Victor, can’t help but point to a famous super-hero precedent; the fact that the first flashback sequence begins with Victor obliterating the word ‘marvel’ really brings the point home. But super-hero stories with protagonists who aren’t particularly heroic have been a large part of the genre for at least thirty years; one thinks of Watchmen, of course, but also a host of books from Mark Gruenwald’s Squadron Supreme to Epic’s Shadowline comics to Suicide Squad to Thunderbolts to the Wild Cards novels to games like White Wolf’s Aberrant. Mark Millar’s made a career out of playing with the idea, from Saviour to Ultimates to Civil War to Wanted. The idea of characters with powers but no overriding sense of heroic mission or responsibility — Spider-Man without Uncle Ben’s death — is really quite well-established. Even the idea of the religious antagonist is a venerable cliché (one thinks, for example, of X-Men: God Loves, Man Kills.)

What is interesting about Vicious is that it goes a step further, removing costumes and masks as well, avoiding a plot driven by fight scenes. Is it appropriate to talk about the book as a super-hero story without those signifiers of the genre? Is it best viewed as urban fantasy? Or is there a difference? What makes a story one genre and not another?

What is interesting about Vicious is that it goes a step further, removing costumes and masks as well, avoiding a plot driven by fight scenes. Is it appropriate to talk about the book as a super-hero story without those signifiers of the genre? Is it best viewed as urban fantasy? Or is there a difference? What makes a story one genre and not another?

I think there are some aspects of super-hero fiction recognisable in the book, things you often find in super-hero stories. Powers deriving from trauma. Powers related to (and inextricable from) character. Enemies locked in struggle. An urban environment as the setting for battle. Is it enough?

Maybe not for everyone, but it is to me. I think Vicious is interesting precisely because it straddles genres. It attenuates some of the signifiers of the super-hero genre (costumes, code-names, and so on) while maintaining others. And the result, I feel, moves the story in the direction of another genre. It moves it toward the gothic.

I’ve written here before, several times, that the super-hero genre and the gothic genre are deeply related and indeed that the super-hero story was born out of the gothic. Schwab’s story moves the super-hero tale back toward the gothic. It starts in a cemetery. Death and resurrection are key. As is villainy. The story climaxes at midnight. In all, it seems to sit astride these two genres, nodding now in one direction and now in another.

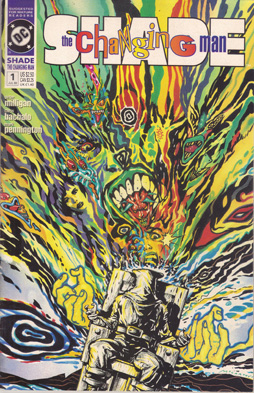

It’s an example of what happens when you take heroism out of super-heroes: you’re left with a sense of horror. One thinks of Alan Moore’s use of the Justice League in his Swamp Thing run — instead of being familiar heroic figures, they become strange and frightening (“There is a house above the world where the over-people gather” has to be one of Moore’s most memorable lines). The characters in Vicious aren’t written on the same scale, but the same principle applies. It comes to feel a little like some of the early Vertigo comics, the Morrison and Pollack Doom Patrol, perhaps Nocenti’s Kid Eternity or Peter Milligan’s Shade: clear super-heroic elements mixed with a greyer world and some elements of horror. It’s not as complex as the best of the Vertigo books, but has a narrative drive many of them lacked.

It’s an example of what happens when you take heroism out of super-heroes: you’re left with a sense of horror. One thinks of Alan Moore’s use of the Justice League in his Swamp Thing run — instead of being familiar heroic figures, they become strange and frightening (“There is a house above the world where the over-people gather” has to be one of Moore’s most memorable lines). The characters in Vicious aren’t written on the same scale, but the same principle applies. It comes to feel a little like some of the early Vertigo comics, the Morrison and Pollack Doom Patrol, perhaps Nocenti’s Kid Eternity or Peter Milligan’s Shade: clear super-heroic elements mixed with a greyer world and some elements of horror. It’s not as complex as the best of the Vertigo books, but has a narrative drive many of them lacked.

Like those books, it’s not terribly concerned with establishing a world. EOs exist in the shadows, essentially urban legends. There doesn’t seem to be any organisation among them. There’s no sense that they’re a recent development, or conversely that they’ve affected history in any meaningful way. By and large, the characters seem to have relatively low-level powers, and the connection between near-death and the development of powers is left relatively vague. There’s no real exploration of how the EOs’ powers make sense scientifically (but then the inability to rationalise powers is another gothic touch: these things exist outside of our understanding). One character does get the power to raise the dead, which in addition to being highly gothic in and of itself, also hints at a sequel: if surviving a near-death experience gives you super-powers, does resurrection bring powers as well?

Maybe there’ll be more books to explore this, maybe not. Vicious stands as a fine story on its own. I’m not sure it has as much to say about heroes and villains as it would like. But it’s fascinating to see the gothic emerging from under the skin of the super-hero genre. And as a character study, it succeeds, integrating flashbacks while maintaining narrative momentum. It reads smoothly, swiftly, and well.

Matthew David Surridge is the author of “The Word of Azrael,” from Black Gate 14. His ongoing web serial is The Fell Gard Codices. You can find him on Facebook, or follow his Twitter account, Fell_Gard.

Matthew,

A fine review – and very timely. This book has been sitting in my Amazon cart for a few weeks, and I’ve been wondering whether I want to pull the trigger. Now I’m sure I do.

Glad be to be of help!

[…] the Gesta Romanorum, Mary Gentle’s The Black Opera, Stella Gemmell’s The City, V.E. Schwab’s Vicious, Olga Slavnikova’s 2017, Jan Morris’ wonderful Hav, Phyllis Ann Karr’s Wildraith’s Last […]