Something Unspeakable Has Come Home: 1972’s Deathdream Revisited

One of the most enduring tales in all horror literature is W.W. Jacobs’s classic 1902 shocker, “The Monkey’s Paw,” in which a father acquires a magic talisman (the paw) from a soldier home from service in India. The paw supposedly grants three wishes — wishes that of course come at a price. Not really believing that it will work, the father wishes for two hundred pounds to pay off his house. The next day, his son is killed (“caught in the machinery”) at the factory where he works and in compensation, the company presents the family with…two hundred pounds.

One of the most enduring tales in all horror literature is W.W. Jacobs’s classic 1902 shocker, “The Monkey’s Paw,” in which a father acquires a magic talisman (the paw) from a soldier home from service in India. The paw supposedly grants three wishes — wishes that of course come at a price. Not really believing that it will work, the father wishes for two hundred pounds to pay off his house. The next day, his son is killed (“caught in the machinery”) at the factory where he works and in compensation, the company presents the family with…two hundred pounds.

Some days later, after her boy has been buried, the grief-blinded mother realizes that they’ve only used one wish, and compels the appalled father to use the paw to wish their son alive again. A short time later, they hear a soft knocking at the door, knocking that quickly grows into a deafening fusillade as whatever it is that waits outside the bolted door furiously tries to gain entry. While the ecstatic mother fumbles with the bolt, the terrified father, imagining the mangled horror outside, uses the paw for one last wish. When the door finally swings open, there is nothing there — “The street lamp flickering opposite shone on a quiet and deserted road.”

This powerful tale has been adapted many times over the decades, for stage and radio, for television and movies, and for comics, and it has additionally inspired many stories and films that are not direct adaptations; of these Stephen King’s 1983 novel Pet Semetary may be the most well known. Another example, not nearly as well known as it deserves, is the 1972 low-budget horror film, Deathdream.

The 1970s were a time of anxiety (how little has changed), and one of the great worries of the time concerned veterans returning from the Vietnam War. Returning vets were the subject of countless movies and television dramas, and often these vets were seen as ticking time bombs, potentially disturbed, violent men unalterably changed and cut off from the society they served by the extreme experiences they had undergone.

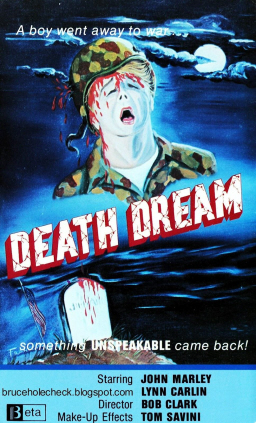

Deathdream (also released in some places as Dead of Night, The Night Andy Came Home, and The Nightwalk) fits into this mold, but with a difference; where a mainstream, all-star, big-budget film like 1978’s Coming Home treats the subject of veteran re-entry in a realistic “respectable” fashion, Deathdream uses the framework of supernatural horror to give the story an extra jolt. Add “The Monkey’s Paw” to Born On the Fourth of July, stir well, and you get Deathdream.

Deathdream (also released in some places as Dead of Night, The Night Andy Came Home, and The Nightwalk) fits into this mold, but with a difference; where a mainstream, all-star, big-budget film like 1978’s Coming Home treats the subject of veteran re-entry in a realistic “respectable” fashion, Deathdream uses the framework of supernatural horror to give the story an extra jolt. Add “The Monkey’s Paw” to Born On the Fourth of July, stir well, and you get Deathdream.

Filmed on location in Brooksville, Florida, on a budget of just $235,000, the movie was the brainchild of writer Alan Ormsby and director Bob Clark. They had previously made Children Shouldn’t Play With Dead Things, a ludicrous, incredibly cheap ($40,000), surprisingly entertaining variant on Night of the Living Dead. Though Children was released after Deathdream, investors were impressed enough with it before its release to get Clark and Ormsby substantially increased financing for their next feature, one that they wanted to be more serious than the over-the-top comic zombie gorefest of Children. (Hmmm… over-the-top comic zombie gorefest of Children… that’s a helluva phrase.) Ormsby had written a script about a troubled — extremely troubled — soldier come home; the idea was sparked by “The Monkey’s Paw” and Irwin Shaw’s 1936 play, Bury the Dead, in which bitter war casualties refuse to be buried.

Deathdream opens with a brief scene in Vietnam; on a confused night patrol, we see a young soldier get killed. We don’t even know his name. Then we’re at that soldier’s home as his father Charles (John Marley), mother Christine (Lynn Carlin), and sister Cathy (Anya Ormsby) sit down to a family dinner, a meal enlivened by cheerful banter and obvious affection. We have only a moment to see the family in happy normality, however. The doorbell rings, and a messenger from the Army delivers the news that their son, Andy, has been killed.

This is the most horrifying moment in this horror movie, seeing each person deal with shock, disbelief, and anguish. It’s a beautifully played scene. Later that night, Charles finds his wife sitting up alone holding a candle, chanting her belief that Andy is alive, that the Army lied, that he’s coming home.

And he does. In POV shots we see Andy hitchiking a ride into town (the truckdriver who gives him a lift will be discovered the next day dead in his cab, with a slashed throat) and we follow him as he walks up to his sleeping house. His family hears something downstairs and, after an anxious creep down the darkened stairs, are overjoyed to find their son alive — the Army was wrong. “They actually said that my son was dead!” Charles says. “I was,” Andy replies, and after a long, frozen moment, everyone laughs. Andy always was a cut-up.

It quickly becomes clear, however, that Andy has changed. He sits in his bedroom with the lights off, silently rocking in his old chair for hours at a time. He doesn’t want to meet any old friends or have any kind of celebration. He’s not interested in eating. He doesn’t look well – his complexion is pale and pasty. Andy starts taking long walks around town late at night, walks that invariably end up in the cemetery, where we see him scratching something — we don’t know what — into a headstone.

It quickly becomes clear, however, that Andy has changed. He sits in his bedroom with the lights off, silently rocking in his old chair for hours at a time. He doesn’t want to meet any old friends or have any kind of celebration. He’s not interested in eating. He doesn’t look well – his complexion is pale and pasty. Andy starts taking long walks around town late at night, walks that invariably end up in the cemetery, where we see him scratching something — we don’t know what — into a headstone.

And emotionally, Andy seems… not quite there. He acts flat, stiff, almost… dead. Christine is in denial about this as she was about the news from Vietnam, but Charles suspects that something is seriously wrong. This is confirmed one day when Andy is sitting on a lawn chair in the yard and several admiring neighborhood kids gather around him, asking questions. Why isn’t he wearing his uniform? Did he kill anyone? Andy seethes, getting angrier and angrier at these questions until a boy proudly tries to demonstrate his karate skills by chopping at Andy’s arm. Andy grabs the boy’s arm and brutally twists the child to the ground.

The family dog runs up, snarling (the pooch hasn’t liked Andy one bit since his return) and Andy grabs the dog by the throat and strangles it in front of the horrified children; Clark’s camera zooms in close on Andy’s glaring, insane eyes and his clenched teeth, his lips drawn back in an animal snarl. In its suddenness and violence (and because of its usually sacrosanct targets, a child and a family pet), this is a truly shocking scene.

From that seeming low point, things go downhill even further. Andy visits the family doctor (veteran soap star Henderson Forsythe) and stabs him to death in a scene reminiscent of similar moments in Psycho and Night of the Living Dead. This is where we most clearly see that the only thing animating Andy now is rage; everything is dead in him except his fury at being dead and his hatred of those who sent him to that death.

Just before he kills the doctor, Andy says, “I died for you, Doc — why shouldn’t you return the favor?” After the murder, Andy fills a syringe with the doctor’s blood and shoots up with it, a reminder of the drug addictions that many soldiers brought back with them from the service. Before injecting the blood, Andy had started to look a little decayed, but the injection seemingly rejuvenates him… for a little while.

Things now come to a climax quickly. While his father figures out that Andy has killed the trucker and the doctor and tries to throw the police off the trail, Andy’s sister Cathy convinces him to go on a double date with her and her boyfriend Bob (Michael Mazes), and the girl Andy left behind, Joanne (Jane Daily). When Bob and Joanne show up at the house, Andy walks down the stairs wearing black sunglasses and black gloves — nothing spoils a date faster than blood-red eyes and maggots falling out of the rotting hole in your wrist.

Things now come to a climax quickly. While his father figures out that Andy has killed the trucker and the doctor and tries to throw the police off the trail, Andy’s sister Cathy convinces him to go on a double date with her and her boyfriend Bob (Michael Mazes), and the girl Andy left behind, Joanne (Jane Daily). When Bob and Joanne show up at the house, Andy walks down the stairs wearing black sunglasses and black gloves — nothing spoils a date faster than blood-red eyes and maggots falling out of the rotting hole in your wrist.

Joanne’s joy at seeing Andy instantly fades as he pushes away her embrace and speaks to her in a dry, utterly unemotional tone. Joanne is crushed. This scene is almost as painful to watch as the death notice scene.

The couples go to a drive-in movie (1972, folks!) and while Cathy and Bob go to the snack stand, Andy kills Joanne. When Cathy and Bob return, Andy is covered with blood, blood that this time has done him no good, as he is now in an advanced and rapidly accelerating process of decay.

Andy strangles Bob with a speaker cord (we’ve all wanted to do that to someone at a drive-in) and speeds away in the car. Arriving at home, Charles confronts Andy and tries to shoot him, but can’t bring himself to pull the trigger on his son. Christine leads Andy out of the room, and we hear Charles shoot himself.

Charle’s misdirection didn’t fool the police for long, and they pull up as Andy’s mom leads a now literally falling to pieces Andy to the car. The police shoot Andy twice, but that doesn’t stop him. Mother and son speed away with Christine asking, “Where, Andy? Where?” He directs her to the cemetery, where he staggers and finally crawls to a shallow grave. Falling into it, Andy starts pulling dirt over himself and then stops, still and dead at last. The camera moves up and we see what he had scratched into the headstone on his earlier trip to the cemetery: Andy Brooks 1951-1972. The soldier has truly come home at last.

Deathdream is a low-budget movie and it doesn’t completely transcend those limitations. Some scenes are lit well and some aren’t. The acting is variable; as is common on these kinds of movies, the cast is a mix of professionals and local amateurs.

Deathdream is a low-budget movie and it doesn’t completely transcend those limitations. Some scenes are lit well and some aren’t. The acting is variable; as is common on these kinds of movies, the cast is a mix of professionals and local amateurs.

But far more went right on the film than went wrong. After a bit of a slow start, the story has a good pace, and Bob Clark (who went on to greater success with Porky’s and A Christmas Story) handles moments of both family interaction and shocking horror very effectively; this is horror in a believable domestic setting and it’s all the more powerful for that. The makeup (by Ormsby and Tom Savini — one of his first credits) is for the most part convincingly gruesome.

The leading players are solid. John Marley (fresh from the horse stables and blood-soaked sheets of The Godfather) is perhaps too old for the father, but he gives it everything he’s got, and he makes Charles’s anguish and despair moving. To his credit, he clearly took his role in this cheapie as seriously as anything he ever did. Lynn Carlin and Anya Ormsby are fine as mother and sister.

But the performance that everything hangs on is Andy and Richard Backus (in his first film) is perfect in the role. He manages to put real menace in his stillness and the flickering rage that is always present in his eyes and that startlingly flares into action is absolutely convincing — and frightening.

And, aside from an unfortunate moment or two of ineffective humor, Alan Ormsby’s script is very fine for a movie of this type. The social relevance and the horror don’t fight against or undercut each other; instead, they compliment each other. The veteran’s return theme is there, but is generally understated; Andy is truly the war come home, but Ormsby and Clark don’t beat you over the head with it. The movie isn’t preachy — it’s atmospheric and scary, with some truly nasty shocks, but when it’s over, it leaves you in a more quiet and thoughtful mood than most cheap horror movies do.

Deathdream didn’t get much of a release in 1972, playing mostly in the South, and then appearing occasionally on late night television — back when late night television still showed old movies. But like Andy, it refused to die and has steadily built up a following over the years. In 2010, it was put out on DVD by Blue Underground, with commentaries by Bob Clark and Alan Ormsby, an interview with Richard Backus, and a short feature on Tom Savini.

If you’ve never seen Deathdream, give it a try. If you make the proper allowances, I think you’ll be pleased and surprised. And if you don’t like it, you can just bury it again; maybe it’ll stay there this time.

Saw this on the big scream back in the mid-nineties. What a terrific gem.

Sounds like a great film — I’m surprised I’d never heard of it!

Nick, it used to pop up on late night fairly frequently here in L.A. and the TV guide blurb made it sound intriguing, but in those pre-VCR days I never managed to catch it. Theh the Psychotronic Encyclopedia gave it a rave, and I knew I had to see it. It still took me twenty years to track it down.

http://b-masters.com/2014/02/be-careful-what-you-wish-for-2/

Incidentally, in print, Rambo debuted the same year in First Blood by David Morrell. It also plays as a horror novel critiquing the Vientam conflict under the cover of horror/suspense. The novel First Blood has more of a horror feel than the eventual film adaptation*, though the latter does follow the plot and themes reasonably closely. The novel features Rambo as a spree murderer in the woods.* Kim Newman included First Blood in the Appendix to Horror: 100 Best Books and its sequel. David Morrell notes that he, due to his visa** had to handle political themes carefully, per his loyalty oath.

*This may disappoint more reactionary readers. Those seeking more jingoistic adventure novels should turn to the Nick Carter novels from 1964 to 1990, the literally hundreds of adventure novels about Mack Bolan, and to a lesser degree, the novels about the Shadow as well as Steve Austin, Cyborg/the Six Million Dollar Man (the first Steve Austin novel involves him in the Arab-Israeli conflict).

Incidentally, for a more jingoistic paranormal flipside to Dead of Night, one could consider Cyborg the novel that way. Caidin, in contrast to Morrell (see below), already a long-established author on aviation and more strongly associated with the establishment, does not engage in John Le Carre style social criticism of espionage, at least in the first novel.

**Morrell also came from Canada.

I can’t comment on the possible relation of Rambo/First Blood to Deathdream, as I’ve neither read First Blood nor seen any of the Stallone films. Deathdream can be considered an antiwar film, certainly, but its specific political content is pretty low.