A Review of The Man Who Awoke, Plus a Giveaway

The Man Who Awoke

The Man Who Awoke

Laurence Manning

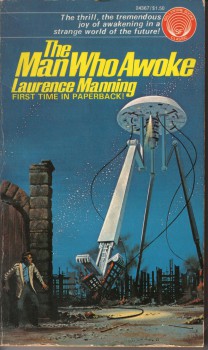

Ballantine (170 pgs, $1.50, 1975)

Back in February, our editor John O’Neill featured Laurence Manning’s The Man Who Awoke in one of his Vintage Treasures posts. I first read the book sometime around the summer (I think it was summer) of 1981 or 1982. I was in high school and had picked up a copy at a local used book store. When I mentioned in the comments that I’d been thinking of rereading it, John graciously offered to let me do a review. I’d like to thank him for the opportunity.

It had been on my mind recently when I read an ARC of Michael J. Sullivan’s Hollow World. Then I attended ConDFW this past February, where the charity book swap had dozens of paperbacks from the late 70s and early 80s in excellent condition. Among the titles I picked up was a first edition of The Man Who Awoke.

The novel was originally serialized in five parts in Hugo Gernsback’s Wonder Stories in 1933. The first part was included in Isaac Asimov’s anthology Before the Golden Age, another book I need to reread. I had enjoyed the first installment, so when I came across the paperback of the whole novel, I snatched it up and dashed home with it, after properly paying for it of course.

The story concerns Norman Winters. He’s a wealthy scientist who develops a method of putting himself to sleep through a process very much like hibernation. I don’t know if this is the first use of what would later come to be called suspended animation, but it had to be one of the earliest. I’ve not read H. G. Wells’s When the Sleeper Wakes, so I don’t know the mechanism Wells used. Manning has his protagonist use this device to search for meaning and happiness in the future.

In the first story, “The Forest People,” Winters places his apparatus in a chamber deep underground, and with the aid of a timer, sleeps for a few millennia, waking in 5000 A.D. When Winters comes out of his chamber, he discovers that the world has reached a state in which humans live in small villages, using trees to supply almost all their needs. Most of the world is covered by forest, and open grasslands are anathema. The time Winters comes from (our present age) is known as the Age of Waste.

The older members of the village where Winters is staying want to harvest some trees to stave off a shortage of food. This doesn’t sit well with the younger members of the community.

“And did you use petroleum for fuel?”

“Of course. We used it in our automobiles.”

“And was it usual to cut down trees just for the sake of having the land clear around them?”

“Well…yes. On my own land I planted trees, but I must say I had a large stretch of open lawn as well.”

Here Winters felt faint and giddy. He spoke softly to the young man who had brought him. “I must lie down I’m afraid. I feel ill.”

“Just one more question,” was the whispered reply. Then aloud: “Do you think we of the Youth Council should permit our inheritance to be used up-even in part-for the sake of present comfort?”

“If it is not done to excess, I see nothing wrong in principle-you can always plant more trees…”

I found much in this section resonated with current events. Manning talks about preserving natural resources, but he makes the discussion general enough that it could apply to more than one set of haves and have-nots today. Winters ends up in the middle of a war between the younger and older members of the community and flees to his chamber, where he sleeps for another 5,000 years.

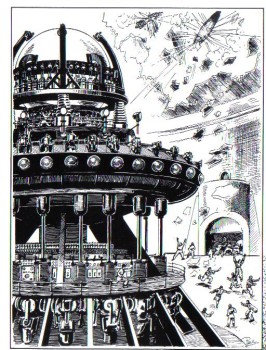

When he awakes, in the story “Master of the Brain”, he discovers a society in which everyone is expected to work in cities. In fact, when he is found wandering the countryside, he is arrested. The world is controlled by a giant thinking machine called The Brain. Over time, each city gets a component of the The Brain. In other words, the world is run by a vast AI networked through all population areas.

The work people are required to do is minimal. They’re on call for a certain period and only work an hour or so a day. Food is provided and they spend the rest of the work shift loafing. When their shift is over, they go to pleasure palaces. Winters ends up helping to destroy the Brain before resuming his sleep.

In the next installment, “The City of Sleep”, another 5,000 years have passed. Humanity is almost a dead race. The few remaining people watch over the rest of the population, which are hooked up to machines which sustain them while they dream. Married couples sleep next to each other. Winters is told it isn’t uncommon that the wife dreams of domestic bliss with her husband while he dreams of having a harem. This time, he helps a group of people escape and resume normal lives.

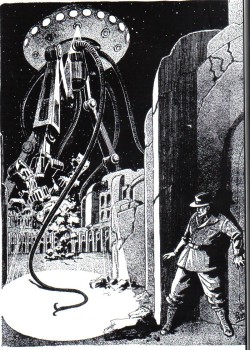

When Winters awakens in 20,000 A.D (“The Individualists”), there are people waiting for him. Historical records of his previous two visits still exist and several biologists want to use Winters for breeding experiments and vivisection. Each person is an individual, only Manning takes the idea to an extreme. Wanting to spend time with others is seen as a mental illness. The cover illustration of the paperback illustrates this portion of the book.

In the final section, “The Elixir,” Manning aids a group of scientists in developing an immortality serum. I found this to be the weakest part of the book. After gaining immortality, Winters roams the cosmos seeking meaning.

There were several things that struck me when reading The Man Who Awoke that I don’t recall registering the first time, or if they did, I’ve forgotten them. Stories from the science fiction pulps of the 1930s have something of a bad reputation today. The conventional wisdom is they’re full of racism. Any women characters are love interests for the men, who don’t contribute to the story otherwise.

Conventional wisdom in the case of The Man Who Awoke would be wrong. By the middle story, Manning notes that the human race no longer has any Caucasians. Everyone but him has dark skin, something he brings up more than once from this point on.

From “Master of the Brain” through the rest of the series, women are given a variety of roles. It’s a woman who arrests Winters when he’s wandering the countryside and a woman is one of the main conspirators against The Brain. Furthermore, sexual relationships in more than one story, when they’re mentioned, are rather open. The way they’re mentioned is more consistent with the 1960s than the 1930s.

The prose in pulp stories from the 1930s is also viewed by many today as being purple and clunky. While there is much justification for this opinion, there are exceptions. I found the prose in The Man Who Awoke easy to read, even though in places it was a little stiff by modern standards.

The story moves along and Manning kept my interest without indulging in too many infodumps. The science was integrated reasonably well into the narrative, although it’s pretty dated in places.

Manning tried to explain how Winters could understand the changes in language in 5,000 year increments, but ultimately he gave it up. I have to give him credit for trying, however. I discussed this and some other shortcomings with the visitor from the past type of time travel story in my review of Hollow World. I’ll not repeat them here because this post is so long already.

I’m more than willing to read more of Manning’s work. Unfortunately, it’s all been out of print for decades.

Almost all of Manning’s fiction was published in the 1930s. He was quite active then suddenly dropped out of writing sf, although he did go on to write a number of well regarded books on gardening.

Almost all of Manning’s fiction was published in the 1930s. He was quite active then suddenly dropped out of writing sf, although he did go on to write a number of well regarded books on gardening.

In his history of early science fiction, Pioneers of Wonder, Eric Leif Davin has a chapter devoted to Manning. He and Sam Moskowitz attempted in the late 1980s to renew interest in Manning. They contacted his widow, who was still alive at the time. There were rumors of an unpublished novel, but no manuscript was ever found. Moskowitz got busy with other projects and ultimately nothing came of their efforts.

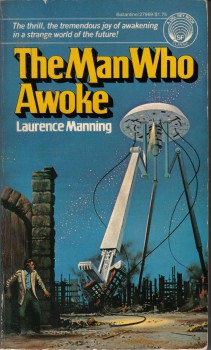

Now, for the giveaway part of this post. I’ve got both a first and a second edition of The Man Who Awoke. The first edition is shown at the top of this page, the second edition at the bottom. Feel free to play Spot-the-Differences. The prize is the first edition of the book.

I will award the prize to the person who, in my opinion, best answers the question: Why is pulp era science fiction and fantasy still relevant today? The contest will run until 11:59 p.m. Wednesday April 30. The giveaway is limited to the US and Canada.

I found copies of Frank R. Paul’s original illustrations in David Kyle’s excellent book, A Pictorial History of Science Fiction.

Keith West blogs way more than any sane person should. His main blog is Adventures Fantastic, which focuses on fantasy and historic fiction.

How do we participate? Email? Post the answer here?

I’m sorry, I wasn’t clear, was I? Please enter the giveaway by posting your entry here in the comments. Hopefully, we will have some discussion based on the entries.

Pulp-era science fiction and fantasy are still relevant because older genre fiction, no matter how dated the technology or concepts, allows us to see how people in the past dreamed about the future. Genre fiction is humanity’s desire to see how history will unfold given life. Who among us doesn’t dream now and then of living beyond our puny mortal span, and seeing the future that we are helping to found with our actions today?

In addition, pulp-era fiction lets us compare our present to what the genre writers of old predicted. Unlike the authors who are no longer among the living, we get the benefit of marveling at what they got right, and sighing with relief when dire things they predicted don’t come to pass.

In genre fiction above all other forms of literature, writers act as living lenses, through which we can see the world in a different way. That is one of the great blessings of the passage of time and death: we get to see the world afresh with each passing year, and through each new person that walks the Earth. Fiction, the written word, are telepathic messages sent forward in time for us to experience and enjoy. Ultimately, they are voices from the void of the past, without which the years behind us would be tragically silent.

Pulp era sci-fi and fantasy are relevant because they give readers a world and characters that more closely resemble our own. And they’re a little more believable because of it. There’s just something that rings true about the morally gray characters and anti-heroes that dominate pulp SFF.

Tolkien gave us reluctant hobbits and noble elves on a quest for the greater good of the world. The pulps gave us Conan the Cimmarian, Eric John Stark, and Fafhrd and the Gray Mouser. They’re violent men accustomed to violent work. It’s not hard to imagine them battling against overwhelming odds with nothing but a sword or a pistol. In fact, it’s hard to imagine them doing anything else.

If Hammett brought crime out of the drawing room and into the alley where it belonged, as Raymond Chandler says, then the pulp SFF authors did the same thing with the fantastic genre. They gave piracy, rebellion, and high adventure back to the cutthroats and criminals who live on the fringe of society. They took us out of Rivendell, and put us on the mean streets of Lankhmar. They showed us the underside of these fantastic worlds, with all of the grit and grime attached.

It’s an influence that’s gone far beyond the pulps and into pop culture at large. If the golden age of sci-fi is responsible for Starfleet Academy, tricorders, and the Prime Directive, then the pulp era gave us the Mos Eisley cantina, obese gangster-slugs, and roguish space smugglers.

[…] my recent review of Laurence Manning’s The Man Who Awoke, I ran a giveaway for a copy of the book in which the […]

[…] I read the book when I was in high school and again about a decade ago, when I did a detailed post on it at Black Gate. […]