Urban Areas: The City, by Stella Gemmell

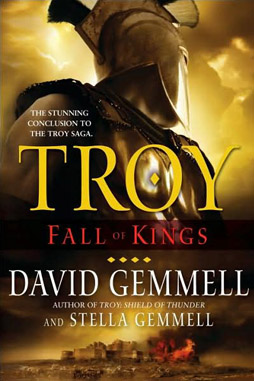

A little while ago, I stumbled on a book that seemed especially worth writing about here: The City, by Stella Gemmell. It’s Gemmell’s first solo novel; she also completed Troy: Fall of Kings, the last book by her late husband, David. David Gemmell was a widely-known heroic fantasy writer — those unfamiliar with his work can see his Wikipedia entry, a wiki dedicated to his books, an obituary from The Guardian, a retrospective of his life and career from this site, and a look back at his first novel, Legend. I’ve only read a couple of his works myself, his early novels Legend and Waylander, but knowing his background I found myself curious about The City.

A little while ago, I stumbled on a book that seemed especially worth writing about here: The City, by Stella Gemmell. It’s Gemmell’s first solo novel; she also completed Troy: Fall of Kings, the last book by her late husband, David. David Gemmell was a widely-known heroic fantasy writer — those unfamiliar with his work can see his Wikipedia entry, a wiki dedicated to his books, an obituary from The Guardian, a retrospective of his life and career from this site, and a look back at his first novel, Legend. I’ve only read a couple of his works myself, his early novels Legend and Waylander, but knowing his background I found myself curious about The City.

It’s the story of a vast, unnamed city at the centre of a sprawling empire, engaged in an ongoing brutal war and ruled by a mysterious immortal. The novel begins with a disgraced general struggling to survive in the labyrinthine sewers that undergird the city, then begins moving freely through a large cast, most of whom are soldiers in the city’s army. It becomes clear that the Emperor’s a tyrant, who must be overthrown — but can any merely human conspiracy survive against his mysterious powers?

The fantasy element of the book’s fairly light, beyond the setting (which itself turns out to have its own secrets). The book’s main focus is on war, battle, and the experience of the individual soldier. It ably moves from plot strand to plot strand, character to character, and occasionally skips forward by years or months. It’s an intricately-plotted book, and I suspect benefits from being read in a short time. Luckily, the style’s clear and plain without being simplistic, driving the reader on quickly through a series of fights and betrayals.

The novel’s primary focus is on the emerging conspiracy against the Emperor, a scheme with many elements. There’s a considerable amount of politics in the book, but I found Gemmell managed the neat trick of making those politics both complex and easily-understandable. She evokes a real sense of a mysterious, corrupt government, seen from the outside and edge-on, and equally a sense of scale to the characters struggling to understand how to fight it and who is using them against it. The use of multiple point-of-view characters is particularly well-handled here, the different perspectives proving a necessary structure to get across the whole of the story.

The novel’s primary focus is on the emerging conspiracy against the Emperor, a scheme with many elements. There’s a considerable amount of politics in the book, but I found Gemmell managed the neat trick of making those politics both complex and easily-understandable. She evokes a real sense of a mysterious, corrupt government, seen from the outside and edge-on, and equally a sense of scale to the characters struggling to understand how to fight it and who is using them against it. The use of multiple point-of-view characters is particularly well-handled here, the different perspectives proving a necessary structure to get across the whole of the story.

There’s something appropriate in a novel about a city — particularly a nameless, central, archetypal City — relying on multiple viewpoints. But at the same time, there’s an extreme focus on the soldiery that limits one’s sense of the City as a place and as a metropolis. There are inns, as is inevitable in almost any fantasy city, but not markets. Libraries but no churches. And no main characters who aren’t soldiers, no merchants or priests or minstrels. To an extent that’s understandable: the ongoing war has led to the conscription of almost every able-bodied person in the City. But rather than establish the sense of a place under siege, it creates (perhaps deliberately) a curiously empty feeling; a void at the City’s heart.

Oddly, the periphery of the City’s much more completely described. There is a sense in which this is primarily a book about wainscots (to borrow a useful term from Clute and Grant’s Encyclopedia of Fantasy) — the spaces between the walls. Characters lurk in sewers and sneak about a palace in secret passages. Those who are not soldiers seem to be beggars. The City is all corrupt heart and oppressed margin, with no space for the depiction of the ‘average citizen.’ For the most part, this is where the emphasis ought to be: these are the most storyable parts of the City. They’re where the narrative interest lies, and the story of a rebel movement hiding in the sewers and outcast spaces of a vast city is a strong one. But without a sense of the City as a place it risks feeling hollow, even pointless.

It is I think a strong choice to only slowly unveil the secrets of the palace at the heart of power, and to keep the main characters well away from it early on. It intensifies the mystery and scale of things, and emphasises how peripheral the characters are — how difficult their task. Slowly it becomes clear that the high-ranking potentates of the city have vast powers, and the book seems for a while like an adventure-fiction inversion of Steph Swainston’s Castle series: where those books focused on an immortal elite at the centre of a command economy, this book shows us the poor and the outcast (some of whom are princes in disguise) struggling as pawns and opponents of the more-than-human inner circle.

It is I think a strong choice to only slowly unveil the secrets of the palace at the heart of power, and to keep the main characters well away from it early on. It intensifies the mystery and scale of things, and emphasises how peripheral the characters are — how difficult their task. Slowly it becomes clear that the high-ranking potentates of the city have vast powers, and the book seems for a while like an adventure-fiction inversion of Steph Swainston’s Castle series: where those books focused on an immortal elite at the centre of a command economy, this book shows us the poor and the outcast (some of whom are princes in disguise) struggling as pawns and opponents of the more-than-human inner circle.

It is true that the demographics and logistics of the City strain credibility — with a countryside devastated by warfare, where does the food come from to feed such a population? How many cultures are present in the City, and how do they get along? But these questions aren’t the point of interest of the story, and it more or less works by ignoring them. It’s about the top-down exercise of power, and the experience of the soldiery. As such, it works.

On the one hand, the result is a perfectly satisfactory military fantasy. On the other, you wonder whether Gemmell could have pushed her ideas a bit further, defined them more clearly. Many of the images she plays with seem inherently resonant, but there’s no sense of the City as archetype, no feel for myth. The symbols that are present seem vague. You notice that the City is largely threatened by water through the course of the book — floods, massive rains, the collapse of sewers and reservoirs — and that one of the characters creates a work of art based around a seascape; you think that this imagery of water must mean something. What, though? Power controlled? Destructive power? One thinks (well, I think) of Babylon, the type of all cities, whose founding myth involved the city-god Marduk defeating the water-monster Tiamat. But that only works if you happen to know that particular myth. The rulers of the city have names derived from Biblical Archangels, so perhaps Babel and the flood are more appropriate references. My point, though, isn’t that Gemmell should have used any particular symbolism in the book; it’s that the recurring threat of death-by-water doesn’t seem to have any well-defined symbolic heft to it that I could see. The City’s no symbol of order against chaos. It’s no symbol of peoples intermingling. It’s no symbol of culture against barbarity. As I read the book, it’s no symbol of anything, except perhaps power. It just is, for the sake of the story.

I note that in general the writing style in this book tends to avoid both specificity and flatness. What I mean by that is this: I think often fantasy writing tends to one pole or another in describing things and places. Either it is extremely detailed and precise — consider E.R. Eddison’s florid Elizabethan descriptions, Clark Ashton Smith’s prose, or even Tolkien’s elaborate landscapes — or it tends to the bare-bones flatness of myth and folktale. Neil Gaiman might be an example of this approach, particularly in his work for younger readers, perhaps Ursula Le Guin, certainly Gene Wolfe; I’m talking here about an approach to surfaces, to the appearance of things. I’m talking about the ways by which the prose style of fantasy approaches the numinous. Gemmell’s work is pitched almost exactly in the middle, avoiding both detail and archetype, and the surprise (to me) is that it works so well. The story is propelled forward, even as nothing in it really sticks in the mind. Things are described as needed, to the extent needed, without any sense of the thing as symbol or the thing as aesthetic object. This approach even extends to plot: an item that might, under other circumstances, have become a quest-object here falls out of the hands of the main characters before they realise what they have, not to reappear until the conclusion.

I note that in general the writing style in this book tends to avoid both specificity and flatness. What I mean by that is this: I think often fantasy writing tends to one pole or another in describing things and places. Either it is extremely detailed and precise — consider E.R. Eddison’s florid Elizabethan descriptions, Clark Ashton Smith’s prose, or even Tolkien’s elaborate landscapes — or it tends to the bare-bones flatness of myth and folktale. Neil Gaiman might be an example of this approach, particularly in his work for younger readers, perhaps Ursula Le Guin, certainly Gene Wolfe; I’m talking here about an approach to surfaces, to the appearance of things. I’m talking about the ways by which the prose style of fantasy approaches the numinous. Gemmell’s work is pitched almost exactly in the middle, avoiding both detail and archetype, and the surprise (to me) is that it works so well. The story is propelled forward, even as nothing in it really sticks in the mind. Things are described as needed, to the extent needed, without any sense of the thing as symbol or the thing as aesthetic object. This approach even extends to plot: an item that might, under other circumstances, have become a quest-object here falls out of the hands of the main characters before they realise what they have, not to reappear until the conclusion.

There is an anonymity to much of the City, even a lack of individuality. There are few signs of a distinctive language, few completely fantastic names or neologisms. Most proper names (Kerr, Guillaume, Khan) seem to come from a mish-mash of cultures — and we do learn that there is a reason for this — with a few others seeming to nod in a very general direction of some source or other: one of the main characters, a disgraced general named Bartellus, seems to recall the Byzantine general Belisarius. But that’s something of an exception. Most names don’t have that kind of individuality and few place-names are actually given. There are no architectural ideas mentioned in the rare bits of physical description we get of the City. Swords are just swords, tools with no particular special qualities, no legends. Everything’s utilitarian, their surfaces worn smooth without the flatness of myth. And as a result, the story moves forward.

(I will note that one of the few aspects of the City’s culture that comes up in the book is the issue of women soldiers. The City seems to have been basically patriarchal, sending males out to fight, until the number of able-bodied males dropped to the point where they had no further reinforcements, at which point the government began drafting women. It’s a point that recurs in a number of ways through the tale, as some of the main characters are female soldiers. At the same time, it’s difficult to see it pointing to any greater theme in the story. Like much else, it seems to be no more than it is, an element of the tale.)

(I will note that one of the few aspects of the City’s culture that comes up in the book is the issue of women soldiers. The City seems to have been basically patriarchal, sending males out to fight, until the number of able-bodied males dropped to the point where they had no further reinforcements, at which point the government began drafting women. It’s a point that recurs in a number of ways through the tale, as some of the main characters are female soldiers. At the same time, it’s difficult to see it pointing to any greater theme in the story. Like much else, it seems to be no more than it is, an element of the tale.)

(At least, as I say, this is how I read the book. It may well be possible to construct an alternative reading, based on the identity of the final hidden chessmaster who conquers the City, the recurring fascination with women warriors, the image of water working away against stone walls, the idea of change working against entrenched edifices. I’m just not sure the story encourages this kind of reading, or that it really coheres with the overall tale.)

In the end, The City is an effective story because the characters are distinctive and memorable. It’s a book that, for better or worse, seems to refuse to stretch itself out into the levels that it perhaps could have, and remains within itself to tell an intricate, polished tale about wars and soldiers and political conspiracies and assassination and chessmasters. That’s good enough. And it may be that I’m underrating the book; some elements seem to hint at certain themes that Gemmell’s content to underplay. I think there was room to bring out those themes a bit further. But as things stand, at the very least the book tells its story swiftly and clearly. That’s a solid accomplishment.

Matthew David Surridge is the author of “The Word of Azrael,” from Black Gate 14. His ongoing web serial is The Fell Gard Codices. You can find him on Facebook, or follow his Twitter account, Fell_Gard.

Even only a few years out from his death and David Gemmell feels largely forgotten, which is a damned shame as most of his books, particularly his early works, pointed the way to the sort of fantasy we have today. I can only recommend works like Legend, Waylander and King Beyond the Gate for everyone reading this post – they may seem plain by today’s standards, but they are books of brilliance.

Agreed Mr. Mammone. I’ve read most all of David Gemmell’s Drenai series and his Jon Shannow trilogy, to include the first

Stones of Power books, Ghost King, and I still plan to read the rest of his books.

Gemmell had the perfect combo of the John Wayne type of hero and the shades of gray between the black and white.

I’ve been interested in this book as well and Mr. Suridge’s review has made me want to read it even more.

“…nothing in it really sticks in the mind.” I excitedly awaited this book for over a year – snagged it up immediately upon sale – read it within…well, a very long month, setting it down to read two other books and some graphic novels in between readings.

One of the biggest reading disappointments I’ve endured in a long while. I totally disagree that “the characters are distinctive and memorable” – they always were just short, as was most of the story. Even wanting to like it, in the end I could not tolerate it. No one should make the mistake of assuming the heritage of David has been extended to or by Stella, even though I applaud her immensely for finishing Fall of Kings and embarking on her own career.

As for James Barclay’s cover blurb, well, I had planned on reading the man’s novels, but that single sentence has managed to push them far down the TBR pile.

I can only agree about Barclay’s writing. I read his first book and loathed every page of it. Chances are he has improved, but why should I waste more of my hard earned money on the chance he’s improved from awful to passable?

Robert Mammone: It’s difficult sometimes to tell how a recently-dead writer is holding up, I think. I’d be surprised if Gemmell’s forgotten about any time soon — the Gemmell Awards established in his memory should do something to keep his name around.

Jason — It’s interesting that we had very different experiences in reading the novel. I tore through it in a day and a half. I think if I’d read it over a month, with other books in between, it would’ve been far more difficult for me to enjoy. I distinctly remember feeling that I could follow the shifts from plot to plot and perspective to perspective because I was going through it all at once.

That said, of course there’s the question of whether the book’s good enough to keep one reading it all at once. It was for me, and not for you. Which happens; if the characters don’t strike a note with you, I’d think this would be a tough book to get into.