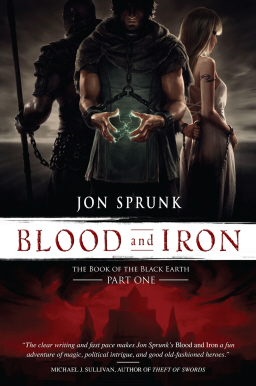

The Series Series: Blood and Iron by Jon Sprunk

Of all the wild re-envisionings of the Crusades I’ve seen lately, Jon Sprunk’s Blood and Iron may be the wildest. His alternate-universe Europeans are recognizably European, but the opposing culture they face is that of a Babylonian Empire that never fell. And why has this Babylon-by-another-name persisted for thousands of years, so powerful that only its own internal strife can shake it? Because its royals actually have the supernatural powers and demi-god ancestry that the ruling class of our world’s Fertile Crescent claimed.

Of all the wild re-envisionings of the Crusades I’ve seen lately, Jon Sprunk’s Blood and Iron may be the wildest. His alternate-universe Europeans are recognizably European, but the opposing culture they face is that of a Babylonian Empire that never fell. And why has this Babylon-by-another-name persisted for thousands of years, so powerful that only its own internal strife can shake it? Because its royals actually have the supernatural powers and demi-god ancestry that the ruling class of our world’s Fertile Crescent claimed.

The Crusades seem to be having a moment in fantasy literature. This is the third novel I’ve covered this year that reimagines them. David Hair’s novel Mage’s Blood separated east and west with a sea so storm-ridden it could only be crossed every twelve years by means of a giant magic bridge, and the twelfth year coming was sure to unleash war. The alternate history in M. Harold Page’s Marshal Versus the Assassins was much more familiar — basically our own, with the addition of a few conspiracies and with unambiguously real miracles.

Jon Sprunk’s book takes the prize for strange worldbuilding. The Akeshian Empire is approximately what the Akkadian Empire might have looked like, had each of its major cities lasted as long and urbanized as complexly as Rome did. When monotheism comes to Akeshia, it arrives as a local heresy run amok, rather than as a foreign faith attracting converts. Akeshia’s gods are not kind gods; its semi-divine ruling caste are not nice people. However, when our hero comes to understand them from something closer to their own perspective, he finds much to admire and many people worth trying to save from the civil war that is beginning to take shape around him.

And what about our hero? Horace Delrosa stands in for the 21st century American reader almost too well and I wish Sprunk had shown a little more of the world Horace came from. The novel begins with the shipwreck that strands Horace on Akeshian soil, so we only get to find out about his life in Arnos through flashbacks. We get plenty of those, and considering how often writers are warned away from flashbacks as a technique, I was surprised and impressed that Sprunk handled them well every single time. Horace is running from his greatest mistake, one that cost his wife and child their lives. Having lost them, the only things left that he values are his integrity and his dignity. When the Akeshians take him prisoner and enslave him, Horace finds that he must choose again and again between those two values, because a slave can hardly ever have both — if he is lucky enough minute by minute to hold onto either. Once his magical powers manifest, rival Akeshian factions struggle to control him and he must struggle in turn to learn enough about their culture to preserve his autonomy and, indeed, his life.

Horace’s very virtues drive some of his direst mistakes, a dynamic Sprunk lays out in wonderfully various ways with his supporting characters too. The things the Akeshians do that most shock Horace, and by extension the reader, early in the book are deftly revealed each in turn as heroic. Some of them are disastrous and must be stopped, but they’re heroic nonetheless. The trio of outlanders trapped in Akeshia — Horace, the sort-of-African gladiator Jirom, and the Arnossi woman Alyra who spies for a rival eastern power — all follow ideals and pursue goals that a modern reader can find recognizably heroic, yet the three of them often find themselves aiding opposing factions in the Akeshian civil war. And as the characters wrestle with matters of realpolitik and philosophical cohesion, they also wrestle with their own intimate personal histories. The most surprising of these is a supporting character’s coming-out story, something one rarely finds in rip-roaring adventure stories in the epic fantasy mode. The coming-out story seems to me perfectly organic to the character’s history and I felt that Sprunk wove that thread well among the others in the book.

The one big problem with characterization here is in how the book introduces the young queen of the city state where the action unfolds. When first we meet her, Queen Byleth engages in an act of impressively casual cruelty, described in the sort of terms writers usually reserve when they’re demonstrating how evil their villains are so that readers will boo and hiss them. Later, as we follow the gladiator’s progress through the horrifying system of military training that Byleth has devised for her army of slave-soldiers, Sprunk shows us atrocities that could stand with the worst devised in real history. Yet, after we have seen what is worthy in Byleth and been slowly won over to hope that she completes the process of building a conscience, other characters whose judgment we’re supposed to trust say of Byleth that the people of her city love her because she has rarely been cruel.

“What?” I shouted at the page.

Because she has rarely been cruel, the page reiterated.

“You can’t be serious!” I said.

And then another theretofore reliable narrator tried to confirm this judgment, which I can only conclude is what the author wanted us to think.

![]() I had some difficulty getting back into the story then, at just the moment when the magical and physical combat became so sweepingly cinematic that the book really needed me to suspend my disbelief. I might not have noticed so keenly how much the fictional world’s magic system owes to Avatar: The Last Airbender, but that the author seemed to have changed his mind in the middle of the book about how villainous and how salvageable to make the queen.

I had some difficulty getting back into the story then, at just the moment when the magical and physical combat became so sweepingly cinematic that the book really needed me to suspend my disbelief. I might not have noticed so keenly how much the fictional world’s magic system owes to Avatar: The Last Airbender, but that the author seemed to have changed his mind in the middle of the book about how villainous and how salvageable to make the queen.

When I find glitches like this in an advance review copy, I wonder whether the final version of the text retains the problem. UNCORRECTED PROOF, shouts the cover, sort of the way yellow crime scene tape might shout UNEXPLODED BOMB. It pains me to make note of a problem in characterization that was, for me, so vexing, when it would take only three sentences of fixes to defuse or detonate that problem, and for all I know, the author or an editor may already have dealt with it.

When an inconsistency like the one in Byleth’s characterization crops up, an author has two basic options: either make the character more villainous throughout, or tone down the other characters’ revisionism. Really, it would be more interesting to say that Byleth used to let her worst self choose her actions, but now that she’s changing we’ll all give her a second chance because we’ve gotten a look at what she was up against, than to have the normally reliable characters try to minimize the cruelty of Byleth’s former behavior.

That said, Blood and Iron is overall a strong book, full of powerful imagery and a vivid sense of place, with intriguing historical what-ifs and a sense of moral urgency to match its sense of moral complexity. I’ll be picking up the next volume in this series.

Sarah Avery’s short story “The War of the Wheat Berry Year” appeared in the last print issue of Black Gate. A related novella, “The Imlen Bastard,” is slated to appear in BG‘s new online incarnation. Her contemporary fantasy novella collection, Tales from Rugosa Coven, follows the adventures of some very modern Pagans in a supernatural version of New Jersey even weirder than the one you think you know. You can keep up with her at her website, sarahavery.com, and follow her on Twitter.