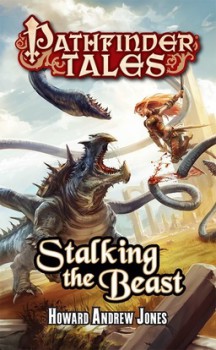

Review of Pathfinder Tales: Stalking the Beast by Howard Andrew Jones

Like many fantasy fans of my generation and the generation before (Gen X and Baby Boom respectively), I was ushered into the genre by Edgar Rice Burroughs, Robert E. Howard, and C.S. Lewis. There were others, of course, but those were the big three. Narnia gave me my first taste of a secondary world populated by mythical creatures, witches and wizards, and talking beasts. Burroughs inched me toward a more Americanized “sword and sorcery” via the “sword-and-planet” Barsoom novels. Howard’s gritty, fabled world of a certain barbaric Cimmerian delivered the full-on S&S.

Like many fantasy fans of my generation and the generation before (Gen X and Baby Boom respectively), I was ushered into the genre by Edgar Rice Burroughs, Robert E. Howard, and C.S. Lewis. There were others, of course, but those were the big three. Narnia gave me my first taste of a secondary world populated by mythical creatures, witches and wizards, and talking beasts. Burroughs inched me toward a more Americanized “sword and sorcery” via the “sword-and-planet” Barsoom novels. Howard’s gritty, fabled world of a certain barbaric Cimmerian delivered the full-on S&S.

Branching out from Narnia, I found my way to the towering, epic high fantasy of J.R.R. Tolkien’s Middle-Earth. And moving on from Howard I stumbled into the dangerous alleyways of Lankhmar in Fritz Leiber’s world of Nehwon.

Not surprisingly, when I got wind of a game that allowed you to invent your own characters and take them on adventures in such worlds via some cool dice, maps, rulebooks, and a little bit of imagination, I was all over it. By the sixth grade I was a devout Dungeons & Dragons player, and Tolkien was my favorite author. Both statements remain true.

So perhaps it’s a bit surprising, given this profile, that I never delved into any of the D&D novelizations — the Dragonlance Chronicles and their ilk. (I did read some of the D&D Endless Quest books, which were in the style of Choose Your Own Adventure, lured by their solo-gaming appeal — a craving that was better met by the Lone Wolf and Fighting Fantasy game books.)

My reading of Howard Andrew Jones’s new novel Pathfinder Tales: Stalking the Beast may be a test case on whether it stands on its own merits because, first, I’ve just never been much into tie-in novels. (Somewhere along the line I read a Star Wars novel, and in junior high I went on a Doctor Who kick. There were also a couple movie novelizations in the mix — inevitably written by Alan Dean Foster. But when it comes to full disclosure on that point, there’s just not much to disclose.)

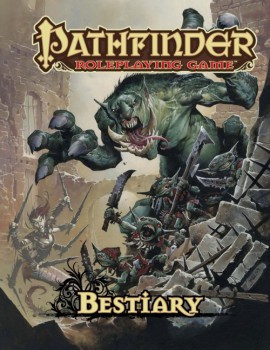

Second, while I continue to play 3.5 edition D&D, I’ve never played the Pathfinder role-playing game. What I’ve heard second-hand I’ll tell you, and those better informed on that front can correct me if any of my second-hand knowledge is off: It was basically Paizo Publishing’s version of third edition D&D, introduced to capitalize on Wizards of the Coast’s open license to the d20 system. When WOTC chose to discontinue third edition completely with their launch of fourth edition D&D, Pathfinder became the de facto reigning third-edition king, filling the ill-advised gap left by those coastal spell-casters. And while fourth edition D&D sank under its own attempt to appeal to the World-of-Warcraft videogame crowd, Pathfinder got huge, and soon started outselling D&D. And from their beach the wizards looked on, muttering, “We could be doing that,” but no, they had abdicated their own power in trying to placate their overlord Hasbro, insatiable deity of toys.

Second, while I continue to play 3.5 edition D&D, I’ve never played the Pathfinder role-playing game. What I’ve heard second-hand I’ll tell you, and those better informed on that front can correct me if any of my second-hand knowledge is off: It was basically Paizo Publishing’s version of third edition D&D, introduced to capitalize on Wizards of the Coast’s open license to the d20 system. When WOTC chose to discontinue third edition completely with their launch of fourth edition D&D, Pathfinder became the de facto reigning third-edition king, filling the ill-advised gap left by those coastal spell-casters. And while fourth edition D&D sank under its own attempt to appeal to the World-of-Warcraft videogame crowd, Pathfinder got huge, and soon started outselling D&D. And from their beach the wizards looked on, muttering, “We could be doing that,” but no, they had abdicated their own power in trying to placate their overlord Hasbro, insatiable deity of toys.

Predictably, Pathfinder is now the hot item with all sorts of tie-in merchandise, including a novel line that releases a new installment every two months. The Pathfinder Tales Library now includes over twenty titles. This is one of them. So, really, what can one expect?

Robert M. Price once wrote of another sword-and-sorcery title that it “is much better than it needs to be.” He meant it as high praise, if also a somewhat condescending swipe at the genre. I want to start with that quote, because frankly I went into Pathfinder Tales: Stalking the Beast — a bi-monthly-subscription novel based on a role-playing game — without terribly high expectations. What I hoped is that it would be “fun.” I hoped it would maintain my interest, because countless have been the books — by both high-fantasy imitators of Tolkien and S&S imitators of Howard and Leiber — that have disappointed on that front. Yes, one wants all the trappings of those enchanted realms, but one also needs characters that are engaging, whose challenges and conflicts one can become invested in. All too often this is not the case, and one’s eyes quickly glaze over as the distant barbarian bruises his way to a foregone conclusion.

I am happy to report that Jones’s novel is “much better than it needs to be,” but not without first challenging the statement itself. Whether one is laboring to produce the next Nebula winner or writing an installment in an RPG tie-in series, one should always bring the A game. Either book might be taken down from a shelf a hundred years from now; either might be a young reader’s first introduction to the limitless riches of speculative fiction.

That said, Stalking the Beast can hold its own on any bookshelf. Let me reiterate, I’m judging it as a stand-alone novel because I’ve never played the game nor read any of the other Pathfinder books. I couldn’t put it down. It never sounded a false note. By the time I finished, I had realized this: when I pick up a new fantasy novel, what I want — what I anticipate — is what Stalking the Beast delivers. In short, this was the most satisfying sword-and-sorcery novel I’ve read in a good long time.

The general contours of the world will be immediately familiar to anyone who has ever played D&D; the races, the spells, many of the monsters are iconic (we even get an attack by owlbears!). The most notable divergence is that firearms exist in this world, although they are only advanced to the musket/muzzleloader stage and are exceedingly rare (in a world where magic missile spells and rapid-firing acid wands are not uncommon, there is probably not quite as much incentive to pursue the slow and notoriously risky technology of gunpowder).

The premise is what piqued my interest originally. From the back cover:

When a mysterious monster carves a path of destruction across the southern River Kingdoms, desperate townsfolk look to the famed elven ranger Elyana and her half-orc companion Drelm for salvation. For Drelm, however, the mission is about more than simple justice — it’s about protecting the frontier town he’s adopted as his home, and the woman he plans to marry. Together with the gunslinging bounty hunter Lisette and several equally deadly allies, the heroes must set off into the wilderness, hunting a terrifying beast that will test their abilities — and their friendships — to the breaking point and beyond. But could it be that there’s more to the murders than a simple rampaging beast?

The beast, incidentally, is represented quite fetchingly on the cover. As cool as it looks, though, the reader soon learns that it poses a further challenge to our ragtag bunch of hunters: in the book it is also invisible. (Not a spoiler: that information is revealed in the sample passage printed on the first page of the book.)

Sounds fun, but the book delivers much more than just a fun adventure. The characters make it work; they are why it lingers in the mind after the last page is turned.

Sounds fun, but the book delivers much more than just a fun adventure. The characters make it work; they are why it lingers in the mind after the last page is turned.

The tale is told in third-person with limited omniscience, the narrator being privy to the thoughts and feelings of three characters, although only one at any given time. The chapters alternate among these three point-of-view (POV) characters: Elyana the elven ranger, Drelm the half-orc, and Lisette the bounty hunter. Each chapter is sub-headed by the relevant character’s name, even though it quickly becomes clear within the first few sentences which character we’re following. In its favor, seeing the character’s name at the head of each chapter orients us right away to the particular outlook we are about to be immersed in.

[There may be one or two little spoilers from this point on, although only with regard to character motivations — I won’t be giving away any of the book’s many plot twists, double-crossings, and other surprises.]

Elyana is the character with whom I felt most at ease. As in the adventuring party itself, she is a reassuring presence — wisdom borne of two hundred years experience, innate intelligence, and empathy unusual for an elf (at least toward non-elves) are combined with near-superhuman fighting prowess and other skills of a high-level ranger to make her a natural and trustworthy leader. Her thoughts — as she unravels the mystery of the rampaging beast and its motives, as she confronts the horrors of losing party members, as she tries to anticipate betrayals by companions who may have conflicting ulterior motives — most closely mirror the reader’s own. At different points throughout the narrative, other characters wonder at why she hides her light under a bushel, so to speak — why she remains little more than a member of the guard of Delgar, a town that someone dismisses as just another of innumerable dung heaps that quickly rise and fall in the far-flung southern reaches of the River Kingdoms. Why indeed, when she could really make a name for herself on a larger stage?

The answer to that question brings us to our next POV character, the half-orc Drelm. He and Elyana have developed a special bond of friendship (best described as a platonic brother-sister relationship). As one character astutely observes, when an elf develops such an attachment to one of the short-lived races, said elf — who will see this dear friend grow old and die in a fraction of the elf’s own years — is strongly motivated to make sure the friend is well situated. Delgar may not be a rational fit for Elyana, but it seems the perfect place for Drelm to marry and settle down and bounce little quarter-orc babies on his knee.

Drelm, counter-intuitively but interestingly, breaks the typical berserker-barbarian mold. He worships Abadar, god of “cities, wealth, merchants, and law.” When the story begins, he may be the only soul in all of Delgar who does: Delgar is neither wealthy nor a city, and its location in the hinterlands makes it a refuge for people who are steering clear of urban laws. Drelm is diligent about the law, but there are two things that save him from being a blow-hard, holier-than-thou paladin type (characters that can be so annoying they can sink a whole campaign): he is genuinely good-hearted, and is the rare sort who recognizes that the law is made for the people, not the reverse. (I’m reminded of Jesus’ retort to the Pharisees who tried to catch him in breaking the Sabbath: “Was the Sabbath made for man, or man for the Sabbath?”) He also recognizes the greater wisdom of his comrade Elyana, and so is content to defer to her judgment. The townsfolk of Delgar revere him, appreciating him as a valuable protector between them and the terrors of the wild lands beyond the town limits — such as the titular beast that appears from nowhere and begins a seemingly random campaign of massacre. As the betrothed of the mayor’s daughter, he is also their future leader (and in a place like this, you could do a lot worse).

Drelm, counter-intuitively but interestingly, breaks the typical berserker-barbarian mold. He worships Abadar, god of “cities, wealth, merchants, and law.” When the story begins, he may be the only soul in all of Delgar who does: Delgar is neither wealthy nor a city, and its location in the hinterlands makes it a refuge for people who are steering clear of urban laws. Drelm is diligent about the law, but there are two things that save him from being a blow-hard, holier-than-thou paladin type (characters that can be so annoying they can sink a whole campaign): he is genuinely good-hearted, and is the rare sort who recognizes that the law is made for the people, not the reverse. (I’m reminded of Jesus’ retort to the Pharisees who tried to catch him in breaking the Sabbath: “Was the Sabbath made for man, or man for the Sabbath?”) He also recognizes the greater wisdom of his comrade Elyana, and so is content to defer to her judgment. The townsfolk of Delgar revere him, appreciating him as a valuable protector between them and the terrors of the wild lands beyond the town limits — such as the titular beast that appears from nowhere and begins a seemingly random campaign of massacre. As the betrothed of the mayor’s daughter, he is also their future leader (and in a place like this, you could do a lot worse).

Drelm, being not a deep thinker and basically a man of action, is the least interesting of the three POV characters, which is not to say his chapters were ever uninteresting. Jones uses him deftly, giving him battle-heavy passages where he is in the forefront of the action. (Drelm’s propensity to throw himself into combat and let instinct take over makes him a frightening adversary, but it also gets him wounded a lot — just like your typical “tank” in a campaign. This becomes something of a recurring joke: two characters at different points note how he would have been dead on various occasions had they not been handy to save him.) Even a couple action-lite chapters early on, which establish the surprisingly innocent way Drelm views other people and his own role in the world, provide effective contrast to the perceptions of both Elyana and the third POV character, Lisette.

Lisette is by far the most complex and conflicted of our POV characters. She is a gun-toting bounty hunter who gets roped in to the hunt for a quite different reason than putting down the beast — someone knows about her secret past as an assassin with the Black Coil and manages to coerce her out of retirement. The job description of her gruff dwarf sidekick is to reload her rifles and to dispose of bodies, and other than the none-to-friendly dwarf, she seems to have no friends. She is a dangerous, nasty piece of work, and fascinating. Without the insight to her thoughts, she would seem entirely cold-blooded. What we learn is that she is just very cynical, a worldview formed by experience. It is humorous that just about everything Drelm does is met with outright skepticism by her. When he collects money from her dead targets to turn over to the town coffers, she thinks he must at least be skimming from it. When she surreptitiously follows him and observes a courtship rendezvous with his betrothed, she is flabbergasted that the half-orc acts the perfect gentleman:

“Drelm was as dull and respectable as dirt. Almost any other man she’d ever met would have had that plump and bosomy peaches-and-cream piece bent over a bench and moaning the moment the garden door shut, but Drelm was taking his lunch with her like a country squire.”

When Lisette finally figures the half-orc is not playing some angle, she concludes he must just be really stupid, because that’s easier for her to accept than that he might just be good.

We’re not sure if Lisette is someone we should be rooting for (especially given her motives), but I couldn’t help myself. I found myself as invested in Lisette as I was any of the other characters, and could only hope that she’d come around before it was too late. I won’t give away any spoilers here about whether that happens. Her character arc is compelling enough that I hope you read it for yourself.

Elyana and Drelm assemble a hunting party of eighteen, and it includes many colorful and engaging characters — some of whom would be worthy of their own POV in another novel, although here I think it was a wise choice to limit those to three. There is Drutha the Halfling with her canine steed and exploding canisters, Cyrelle with her pack of hounds, Calvonis the aged warrior who seeks vengeance on the beast for his wife and child, Illidian the elven border-patrol commander who has lost two patrol parties and his arm to the beast, and many others. Don’t get too attached to anyone, though (well, you may not be able to help that): when Elyana warns the assembled party at the outset that “some of us here are going to die,” even she is not prepared for the number of fatalities this undertaking will cost.

Elyana and Drelm assemble a hunting party of eighteen, and it includes many colorful and engaging characters — some of whom would be worthy of their own POV in another novel, although here I think it was a wise choice to limit those to three. There is Drutha the Halfling with her canine steed and exploding canisters, Cyrelle with her pack of hounds, Calvonis the aged warrior who seeks vengeance on the beast for his wife and child, Illidian the elven border-patrol commander who has lost two patrol parties and his arm to the beast, and many others. Don’t get too attached to anyone, though (well, you may not be able to help that): when Elyana warns the assembled party at the outset that “some of us here are going to die,” even she is not prepared for the number of fatalities this undertaking will cost.

The hunt will take them to such wondrous places as the Wilewood, where the strange fey spirits of “the First World” who rule there are portrayed about as effectively and disconcertingly well as I have seen in this type of story (DMs: you want to know how to role-play fey-lord NPCs? Read these passages).

We are thrown into the thick of multiple detailed encounters with the main quarry, plus a bevy of other monstrous foes, and when it comes to fantasy combat sequences Jones’s writing is of the first order.

One general spoiler about plot here: as the story progresses, we come to find that religion plays a big role. There is a secret cult involved, and revelations about how religion and politics have colluded in high places, such that some who may seem to be allies are, in fact, corrupted. This theme — with related issues of duty and fealty to law — is never intrusive, but gives characters opportunity to make some insightful observations, as when Elyana accuses an Oaksteward: “You do as you’re told. A great deal of evil is done in this world by people who claim they merely do what they’re told.” The Oaksteward counters, “A greater deal is done by those who will not follow the laws.” Sounds like a debate I’m hearing every time I turn on the news.

Tolkien made a distinction between allegory and applicability. Nothing in The Lord of the Rings was meant to be allegorical, he vehemently contended, while acknowledging that some of it could certainly be applicable to contemporary issues (i.e., the Ring was not meant to be read as the atomic bomb, but one could draw parallels to make an analogical point). Likewise here: cult members who see no moral problem with wreaking death and destruction on those who do not worship their god? It is an all-too-recognizable worldview — that of the fanatic, be it a Middle-Ages inquisitor or a modern-day terrorist. This is all handled incisively and sensitively; in fact, it leads to a beautiful (and completely unexpected) denouement that proves to be inspirational.

Tolkien made a distinction between allegory and applicability. Nothing in The Lord of the Rings was meant to be allegorical, he vehemently contended, while acknowledging that some of it could certainly be applicable to contemporary issues (i.e., the Ring was not meant to be read as the atomic bomb, but one could draw parallels to make an analogical point). Likewise here: cult members who see no moral problem with wreaking death and destruction on those who do not worship their god? It is an all-too-recognizable worldview — that of the fanatic, be it a Middle-Ages inquisitor or a modern-day terrorist. This is all handled incisively and sensitively; in fact, it leads to a beautiful (and completely unexpected) denouement that proves to be inspirational.

And this is yet another thing that Jones gets right. He weaves in the various religions convincingly, given a polytheistic society in a world where all these gods do exist. Gamers would do well to note how this question of which god one’s character worships can be a real motivator and plot driver in a campaign, and not just a determinant of which list of spells to select from.

All the magic items and spells and healing powers with which RPG players are familiar are here, but they are woven in so seamlessly that they feel completely natural within the bounds of this secondary-world’s reality. When someone dons a healing ring or when a ranger lays on hands to heal a comrade, it doesn’t stand out like the handy game-reset mechanic that is its antecedent. When you’re immersed in this world, you can easily forget that these were drawn from game elements. That is well worth noting, because it takes an experienced hand to pull off such a transmutation. So solidly is the story constructed, we could reverse-engineer plot points back to the underlying game mechanics and pinpoint, for example, when a particular character suddenly multi-classes, but only in retrospect — such thoughts are likely to be far from one’s mind in the heat of the story, so beautifully and naturally does it unfold within the contours of the gripping narrative.

One more little highlight to illustrate the breadth of pleasures to be found here: in game campaigns, the party will often reach a place where their steeds must be tethered or sent back; once offstage it’s usually a matter of out of sight, out of mind. At a certain point Elyana sends away her horse Calda — with which she has a psychic link — with instructions to lead the other steeds safely back home if Elyana and the others don’t return after a certain period of time. Despite the mental connection, the elf has difficulty communicating just how long the horse should wait, since horses don’t note the passage of time like we do. Elyana and the others do not make it back to the horses, and much later, when she is reunited with Calda, she gets an impression of what the horse experienced on the way home. The horse had “led all of the horses back to Delgar without any incident apart from something that had come out of the water after them. Despite the magic that allowed her to speak to the animal, the horse hadn’t really remembered the details, only that the entire herd had gotten away.”

Little touches like this — exploring such questions as what happened to the animal companions when we were gone? and even if you could communicate with them, what natural species barriers would still be present in understanding one another? — help elevate Stalking the Beast above your typical fare.

All these things the book does right, so what does it do wrong? What criticisms can one note for the sake of a fair and balanced review? I’m afraid I can muster none. There are a few typographical errors — especially missing periods and quotation marks — but that is a criticism for the proofreader. The only time I was ever taken out of the story for a moment was early on when the narrator referred to Lisette once as Elyana. But that’s another thing the proofreader should have caught.

Really, Stalking the Beast delivered all the fun and adventure I could hope for from the packaging (a rare thing in itself), but it brought even more to the table. It brought fascinating characters to life, providing engaging dialogue in equal measure to breakneck action. The story became immersive, the conflicts between sympathetic characters and how they would be resolved drawing me along every bit as much as the physical dangers (and heightening the stakes of those dangers). It touched upon larger themes, and did so in a world of wildly disparate elements that hung together by the terms of the world without ever stretching credulity.

Finally, I was happy that the book takes its time with the denouement: characters whom we have followed and grown close to through some harrowing travails get their time to say their goodbyes, to wrap things up. And I hung on every word of it. Sorry to see them go, and I hope some of them will come back.

RATING: *****(5) out of 5 STARS

Stalking the Beast was published as a mass-market paperback by Paizo Publishing in October 2013 with a cover price of $9.99.

COMMENT FROM GABE DYBING (sent to me via email; he said I could post it here):

Hey, man. Took you long enough to get your post up! Seriously, I look forward to your blog. I start checking on Sundays and spend time perusing the other Black Gate content (much of it quite impressive) until you finally deliver.

You certainly have some inkling, from sporadic texts, of what’s been going on with me farther east here. I have bought the Pathfinder core book. It is streamlined 3.5. I saw a commenter online aptly refer to it as 3.75. All the rules (including the best of the Prestige classes) are together in one massive tome (sans Bestiary). There probably are a number of tweaks, but only one outright innovation (that I can recognize): Combative Maneuver Bonus and Combat Maneuver Defense. These simplify many of the complex battle options like Bull Rush and Disarm.

I have been reading Tim Pratt’s Pathfinder tale City of the Fallen Sky and am REALLY enjoying it. I have sampled some of the free, serialized fiction (all by their stable of novelists-so-far) on Pathfinder’s website. First rate stuff. I have been digitally following the Pathfinder comic book — each issue of which comes with bonus NPCs, creature stats, maps, and adventure ideas! 🙂

What the f*** is going on? When did D&D get so honestly good? What have I been missing?

Unlike you, I have read the early D&D novels. I read Dragonlance Chronicles and Legends. I read the first Forgotten Realms trilogy, the Moonshae trilogy by Douglas Niles (a Wisconsinonian who probably hung out with Gygax) and so enjoyed it that I read a second Realms trilogy set in Mayan South America. I WAS THERE when Driz’zt got his start in The Icewind Dale trilogy.

I have experienced all this, Nick. But never, NEVER, have I been tempted — even when I was a KID — been tempted to call it “quality.” Sure, there are some lasting moments. The character of Raistlin is one of the best drawn in the fantasy canon. His relationship with his opposite, his brother Caramon, is the stuff of myth. And the Legends series begin to read like Myth itself. The Moonshae trilogy has some epic shit. Driz’zt… Well, even in high school the brooding outcast struck me as kind of phony. I guess it’s only natural that he’s the most successful by far.

Here’s why I know that this stuff is “less than quality:” most of these authors don’t take time to write. To allude to your recent post, Nick, it is NOT “better than it needs to be.” The writers certainly put in the bare minimum of effort. Last year I had the ambition to reread the Dragonlance novels. I got through the first chapter, and couldn’t read more after some Draconians rattled by, “armed to the teeth.” I don’t know which was more disagreeable: the offense of the trite cliche or my attempt to visualize the literal description (worthy of a Munchkin card!). 🙂

All of these novels rely way too much on exposition. Suffer through the “Prologues” of later Dragonlance trilogies, I dare you. Try in vain to find any immediate, arresting excitement in the chronological start of the Driz’zt stuff (Homeland, I think it’s called).

Try to ignore how your average character is introduced to the reader by name, race, and class! 🙂

But Pathfinder? Pathfinder is doing something different. As far as I can tell, the genre has had time to learn from the past — or at least care enough to avoid some of the weaknesses of the past. It appears that they are actively recruiting top rate talent. They are hiring WRITERS. And these writers are delivering.

And here’s something else that has — potentially — scared the socks off of me. Why write anything else? Why not write — even if you’re unagented and have little chance of selling to someone like Paios — novels set in D&D land?

Go to your public library. What have we known for years but didn’t quite know how to articulate? Look at this new acquisition. We have a female magic user of some sort, for some reason dressed in leatherette. Oh, it says here on the back cover that she has a vampire companion/protector, and she has to battle armies of undead and close the Rift to the Underworld, Gehenna, in the world of Barek’calon. What is the vast majority of this “fantasy” but imitations of the overall genre itself. These writers seem to be picking and choosing, omitting and retooling, writing stories that perhaps contain arresting characters but lack overall vision.

So I’m not precisely saying that it’s not good. What I’m saying is, if one is going to work in this medium at all, why not allow oneself access to the FULL PALETTE.

What is D&D but the distillation and systematization of EVERYTHING in the fantasy canon? And we LOVE it.

Go ahead and create new lands and new races. We don’t care. Don’t hesitate to call an elf an elf and an orc and orc. You’re not fooling anyone. We know what these things are.

If it’s not D&D, then it’s one minimized, probably outworn aspect of it. Long live Sword & Sorcery.

Gabe

Terrific review, Nick. And thanks for copying over Gabe’s excellent letter! It’s practically a post all on its own. 🙂

[…] I wanted to point everyone to a wonderful review of Stalking the Beast that popped up at Black Gate. I haven’t been much involved with the magazine site for quite a […]

@John: You bet — it was my pleasure!

[…] not too long ago, at least in reference to Howard Andrew Jones’s Stalking the Beast, when Nick Ozment realized that that novel was “better than it needed to be.” I’ve read some Pathfinder novels […]