For Want of a Dragon… The Dragon Lord by David Drake

One of the greatest incentives to start blogging about S&S was that it would force me to read more.

One of the greatest incentives to start blogging about S&S was that it would force me to read more.

For the three or four years before I started my blog, I was reading only a dozen or so books a year, instead of the fifty to sixty I had in the past. If I wanted to have something to write about, I would actually have to read. That part’s worked out very well for me.

Coupled with that was the hope of getting to all those books I’d bought and been meaning to read for years — even decades in a few cases. I would leave used book stores with shopping bags full of books, heady with plans to read them all some day. A lot of the S&S books I hoped to blog about had been in those bags.

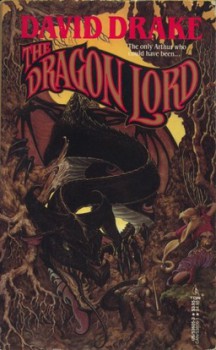

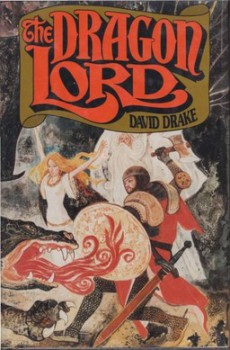

One was The Dragon Lord, David Drake’s tale of an Irish adventurer in the days of King Arthur. Last week, after ten or fifteen years, I pulled it from its dusty purgatory on the bookshelf.

According to the ISFDB, Drake has written seventy novels and over a dozen collections of stories. I’ve read my share of his fiction over the years, including the early Hammer’s Slammers stories and the horror collection From the Heart of Darkness. A few years ago, I read and reviewed his stories about Vettius, a legate in the late Roman Empire. While I thoroughly enjoyed those stories, I had no plans to read Drake again any time soon.

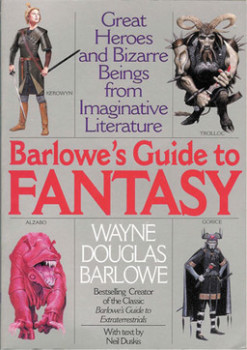

For me to choose to read a David Drake book at this point means that something hooked me. It’s nothing against Drake, but at my age I’ve got stacks of other books picked out. I need a reason to pick out a back row book. In the case of The Dragon Lord, the impetus was a picture from Wayne Barlowe’s Guide to Fantasy.

If you’re a sci-fi fan of the the right age (by which I mean around my age, 47), you should remember Barlowe’s Guide to Extraterrestrials from 1979. Barlowe created dozens of beautiful illustrations inspired by stories from the likes of E.E. “Doc” Smith, C.J. Cherryh, and Poul Anderson.

If you’re a sci-fi fan of the the right age (by which I mean around my age, 47), you should remember Barlowe’s Guide to Extraterrestrials from 1979. Barlowe created dozens of beautiful illustrations inspired by stories from the likes of E.E. “Doc” Smith, C.J. Cherryh, and Poul Anderson.

I would stand in the sci-fi aisle at the Paperback Booksmith in the Staten Island Mall and pour over each page every time I was in the store. It wasn’t until I was in my twenties that I got my own copy. I still pull it out for regular rereads.

In 1996, he followed it up with Barlowe’s Guide to Fantasy, an excellent collection of his renderings of characters and monsters from all sorts of fantasy novels and legends. Like its predecessor, its glossy pages are covered with colorful, detailed interpretations of many classic fictional creations.

Reviewing the Guide’s contents last week, I recalled at least five books I bought based on their pictures. The image to the right is the reason that I bought The Dragon Lord. The cast of its malignant eyes, the broken nose, and the outstretched arms just grabbed me. If he was in the book, I figured it was worth the read.

Alas, sometimes those books, those pictures, those plans don’t lead you to the treasures you hope for. They can’t all be treasures.

There are great individual moments in The Dragon Lord, but overall, the book suffers on several levels. At least the part involving Barlowe’s picture is pretty great.

The Dragon Lord started out as an outline commissioned by Andrew Offutt for a Cormac mac Art book. Offutt had been hired to write a series of Robert E. Howard pastiches by Zebra Books. Because he had difficulty plotting novels, he turned to Drake and another writer to help him out.

Drake goes into detail about this and the history of the novel on his own site. He had already written and published short stories, but was ready to move on to writing full length books. He was a little reluctant to let the outline go because of the great amount of research he did, but he figured watching it get turned into a published novel would be a great opportunity.

Fortunately, it didn’t turn out that way. I say fortunately because Offutt rejected it and Drake, as he states, was quite happy to turn around and complete the novel himself. He stripped out all the references to Howard’s character, renaming him Mael, but otherwise leaving it alone. Taking advantage of the late seventies’ swords & sorcery boom, he completed The Dragon Lord and saw his first novel published in 1979.

Fortunately, it didn’t turn out that way. I say fortunately because Offutt rejected it and Drake, as he states, was quite happy to turn around and complete the novel himself. He stripped out all the references to Howard’s character, renaming him Mael, but otherwise leaving it alone. Taking advantage of the late seventies’ swords & sorcery boom, he completed The Dragon Lord and saw his first novel published in 1979.

It is the 4th century. Mael mac Ronan and his adventuring companion, Starkad, have wound up in Briton during the savage wars between the forces of King Arthur and the Saxon invaders. They quickly realize they are not the right fit for Arthur’s black-uniformed Companions, but they have entered his service at just the right time for a special commission from Arthur and Merlin. Mael finds himself forced to return to his native land in search of the skull of a legendary lake monster.

Drake’s presentation of Arthur goes beyond the grittiness intrinsic to more realistic depictions and strips him of any chivalry. Arthur desires to defeat the Saxons and conquer first Briton and then the world. Throughout the book, he is brave, clever, and cunning, but he is never noble. He wants to be more than a powerful warlord; this Arthur is obsessed with immortal fame by dint of his victories and with extermination of the Saxons and all his other enemies. To do this, he wants Merlin to summon up a dragon and unleash its fiery wrath across the countryside.

The book’s gravest weakness is its disjointed rhythm. Each section, and there are several as Mael travels from pillar to post on his mission from Arthur, feels too unattached from each other. The book reads like a fix-up of short stories with weak bindings between them. There are too many full stops and starts and it never reads like a single seamless story.

The second problem, and this is a personal one, is his treatment of Arthur. On his site, he says he had no interest in the Arthurian stories. Because of that, I believe he felt no fidelity to the legend beyond its basic outlines. So instead of just adding a healthy dose of grimness and realistic grit to the cycle, as Henry Treece did in The Great Captains (which I reviewed on Black Gate last year), he turned Arthur into some sort of wickedly charismatic and cutthroat ruler. There’s a perceptible glint of madness in his eyes.

Arthur’s Companions, armored and on horseback, are more than an effort on the king’s part to create a force like the Roman cataphracts. He has deliberately enlisted men from across the known world so they have no local ties. This has helped him mold them into a unified force bound solely to himself. His ability to bring them victory and his near-magical charisma have convinced them he can indeed conquer the world and they are ready to follow him anywhere. Decked out all in black and fighting under Arthur’s dragon banner, there’s more than a little bit of the Blackshirts to them.

I have too much love for Arthur and the Matter of Britain to be okay with what Drake does to them. Even though Arthur’s a semi-legendary character at best, I expect a little respect for him. And there’s no clear reason for Drake’s treatment. He could have chosen any other king and his warband. Even if his Arthur was just a British warrior in a realistic post-Roman world, there is no need to recreate him as a genocidal megalomaniac. His take on Arthur created a jarring undercurrent that disturbed my entire reading of the book.

Now I did write that the scene featuring Barlowe’s picture was pretty cool, and it is. The individual sections of The Dragon Lord all work on their own to a certain degree. Each tells a part of Mael’s adventures in Ireland and Briton. In these stories, and they really read like discrete short stories, Drake’s tremendous research shines. His Briton is deeply textured. The differing societies and war tactics, and the snippets of various characters’ histories, all help create an authentic-seeming world, fueled by constant war and reeking of life and death.

Now I did write that the scene featuring Barlowe’s picture was pretty cool, and it is. The individual sections of The Dragon Lord all work on their own to a certain degree. Each tells a part of Mael’s adventures in Ireland and Briton. In these stories, and they really read like discrete short stories, Drake’s tremendous research shines. His Briton is deeply textured. The differing societies and war tactics, and the snippets of various characters’ histories, all help create an authentic-seeming world, fueled by constant war and reeking of life and death.

Of Mael’s several adventures, his effort to secure the Sword and Shield of Achilos from the Saxon warlord, Biargram Ironhand, is the highlight of The Dragon Lord. Arriving at Biargram’s steading with hopes of somehow stealing the sword, Mael is tripped up by the recent untimely death of the Saxon. Instead of a quick theft, the Irish warrior finds himself tossed into Biargram’s barrow, where each night the dead man, cursed by black magic, rises. This taut piece of horror reminds me, quite happily, of quite a few fairy tales and sagas.

There are several other very good parts of The Dragon Lord. The best ones involve neither warfare nor the fantastic. At one point in their travels, Mael and Starkad come across a Saxon village preparing to sacrifice a young girl to their harvest goddess. Later, they save a girl from a pair of murderous rapists in their own army. Another terrific moment reveals incredible savagery committed by Starkad that leaves Mael shocked. No events seem gratuitous, but like natural parts of a dark and chaotic era. Mael’s character is developed enough through the novel that his reactions aren’t unexpected or unbelievable. These incidents of de-mythification are exactly what I expect from a story set in an uncompromisingly realistic vision of post-Roman Briton.

I didn’t love The Dragon Lord. It does, though, have great moments. I haven’t even mentioned the very scientific magic of Merlin and his plan for how to bring a dragon into the mundane world. There’s an encounter with a priest and his half-wit mountain of a servitor that culminates in near comic brutality. Mael and Starkad lead one group of Saxons to give up their old goddess for Thor and Odin. There are great bits of cleverness throughout the book. But as a novel — a single, continuous tale — The Dragon Lord is not fully successful. Perhaps if it weren’t King Arthur and Merlin being maligned I would have been more sympathetic.

Still, it’s Drake’s first novel. He approached it as a learning project, and seventy books is proof enough he learned something good.

Thanks for the memory of Barlowe’s Guide to Fantasy! I’m also in my forties, and owned a copy of that at one point. The interpretations of strange monsters and characters were, indeed, often so evocative that one was motivated to hunt down the source material!

I think I would have the same problems you did with Drake’s revisionist presentation of Arthur. Making him more primitive, barbaric, gritty (as many authors have done in recent years) is okay, but to make him a mercenary thug with visions of world conquest is troubling. Of course, since the Arthurian legends are mostly written centuries after events, for all we know the original warlord who may have inspired the legend might well have been closer to Drake’s portrayal. But Arthur is an established tradition (the presence of Merlin as an actual practicing magician reinforces that Drake is drawing upon the legend as much or more so than strictly historical speculation). To so radically diverge from an established character, an author needs good provocation for the sake of the story (think of Gaiman’s brilliant re-imagining of “Snow White,” which presents a version in which the Queen is the misunderstood hero and Snow White is an evil vampire). But as you point out, this extreme make-over of Arthur’s alignment is not integral to the plot of the book.

Ah well. I’ll probably pass this one up in favor of the dozens of books gathering dust in my “bookshelf purgatory” — including some later ones by Drake.

I liked the a lot, considering it was a first novel. It was not perfect, and a little choppy in terms of pacing, but a good, sword swinging time. If you want another gritty take on Arthur, you should try the second book in the Berserker trilogy, The Bull Chief. Written by Robert Holdstock under a pen name, they are truly bloody and grim. In the first book, a young Viking warrior is cursed by Odin to be a berserker, filled with animal rage, and nearly un-killable. At the end of each book, he is “killed”, and re-incarnated a hundred years back into the past. Highly recommended!

@ N Ozment – Yeah, since it wasn’t the book’s focus it was really just a distraction.

@ darkman – There are some great sequences in the book but I found it weak as a book. I’ve been eyeing the Berserker books for some time but they’re too expensive and I’m too cheap.

[…] visited previously in reviews of Henry Treece’s The Great Captains and David Drake’s The Dragonlord, and Keith Taylor’s Bard (1981) is a return to post-Roman Britain in the days of Arthur and […]

It’s been a while and maybe you’re not reading comments anymore, but Drake revisited the Matter of Britain later in “The Spark”, and gave a more sympathetic treatment of the Arthur-figure than he did here.