A Certain Charm Marred by an Air of the Horrible: Count Bohemond by Alfred Duggan

History provides us with real life characters who seem to have stepped straight out of myth. The scale of their ambition or power seems beyond the reach of mortals. Their successes verge on the unbelievable. And yet they are real. Bohemond de Hauteville, Prince of Taranto, was one of those people.

History provides us with real life characters who seem to have stepped straight out of myth. The scale of their ambition or power seems beyond the reach of mortals. Their successes verge on the unbelievable. And yet they are real. Bohemond de Hauteville, Prince of Taranto, was one of those people.

Alfred Duggan’s posthumous 1965 novel Count Bohemond presents the first half of Bohemond’s life: his rise to fame and victory set against the background of the faltering Byzantine Empire and culminating with the near miraculous victories of the First Crusade. This dense and captivating book covers the thirty-five years from Bohemond’s childhood to the height of his success and the capture of the fortified city of Antioch in 1098.

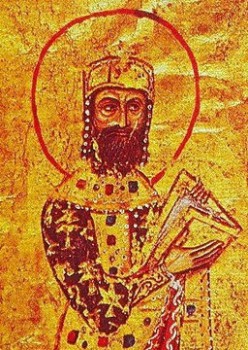

Though she disliked all Normans, and Bohemond in particular, Anna Komene, daughter of Emperor Alexius described him quite laudably in the Alexiad, a history of the Byzantine Empire in the 11th and 12th centuries:

Now he was such as, to put it briefly, had never before been seen in the land of the Romans (that is, Greeks), be he either of the barbarians or of the Greeks (for he was a marvel for the eyes to behold, and his reputation was terrifying). Let me describe the barbarian’s appearance more particularly — he was so tall in stature that he overtopped the tallest by nearly one cubit, narrow in the waist and loins, with broad shoulders and a deep chest and powerful arms. And in the whole build of the body he was neither too slender nor overweighted with flesh, but perfectly proportioned and, one might say, built in conformity with the canon of Polycleitus… His skin all over his body was very white, and in his face the white was tempered with red. His hair was yellowish, but did not hang down to his waist like that of the other barbarians; for the man was not inordinately vain of his hair, but had it cut short to the ears. Whether his beard was reddish, or any other color I cannot say, for the razor had passed over it very closely and left a surface smoother than chalk…

His blue eyes indicated both a high spirit and dignity; and his nose and nostrils breathed in the air freely; his chest corresponded to his nostrils and by his nostrils…the breadth of his chest. For by his nostrils nature had given free passage for the high spirit which bubbled up from his heart. A certain charm hung about this man but was partly marred by a general air of the horrible… He was so made in mind and body that both courage and passion reared their crests within him and both inclined to war. His wit was manifold and crafty and able to find a way of escape in every emergency. In conversation he was well informed, and the answers he gave were quite irrefutable. This man who was of such a size and such a character was inferior to the Emperor alone in fortune and eloquence and in other gifts of nature.

This book is not simply a tale of adventure during the First Crusade. It is about a powerful man slowly realizing how to achieve his ambitions and his emergence as a battlefield genius. In his youth, Bohemond is like a blank slab. He fights alongside his father because it is what he knows how to do. He is not interested in women. When he is dispossessed of his inheritance by his half brother, he fights him to a standstill and establishes his own realm, but it all seems done with little passion. The only animating flame within Bohemond is the vague dream he inherited from his father of carving out his own realm inside the decaying body of the Byzantine Empire.

Not until he reaches his forties and joins his nephew Tancred on the pilgrimage to the Holy Land does Bohemond truly flourish. Each Byzantine act of deceit reveals him to be a nimble thinker, able to respond rapidly to treachery and turn it to his own advantage. He understands how to play off the egos of the numerous Norman and French lords to his best advantage.

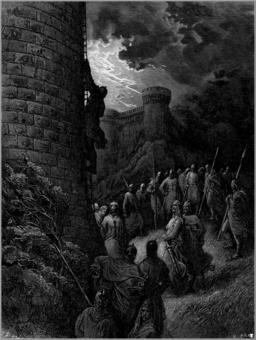

Before meeting the Turks, Bohemond, like most of the other Western lords, fights by charging the enemy line with masses of heavily armored horsemen supported, when available, by crossbowmen. Duggan portrays Bohemond as one of the first Westerners to understand Turkish tactics and respond to them. With tenuous supplies and no hope of relief, he becomes a gambler, willing to risk everything on a single toss of the dice:

In his mind he could picture the whole double action. As though from great height, he saw the lower Orontes, from Antioch up to the lake. Dismounted knights, with their mail and their great swords, could hold the palisaded camp against any Turkish charge; between the lake and the river the infidels must advance in column to fight at close quarters, instead of shooting arrows. How many fit horse had they in the pilgrimage? Not enough, but only the best knights had them. The Frankish charge must go exactly right; there would be no hope of a second. But if it went right the numbers of the infidel would not matter; nothing could withstand it.

There’s a tremendous amount of history in Count Bohemond. The complicated maneuvering between the various Crusader factions, the Byzantines, and the local Christian populations are presented clearly and never left me struggling to follow along. The knights’ interactions are as driven by concerns of noble precedence as they are by their desires for treasure and victory.

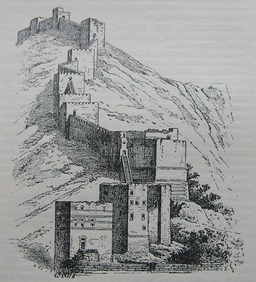

There’s also a strong sense of the geography and architecture of the region. When I finally found an illustration of the walls of Antioch, it matched the image created by Duggan. Being afraid of heights, his description of the crossing of the Cilician Gates mountain pass and the wagons and men who’d already fallen down the side gave me a shiver. And I felt the heat and desperate hunger of the pilgrims outside the walls of Antioch.

Duggan brings to life this turbulent world and culture where Bohemond could exist and fulfill his desires. He is a hard man ready to make hard choices and harsh judgments, as well as take astonishing risks and undertake acts of great courage.

Unlike so many contemporary authors writing about the past, he doesn’t bring an admonishing eye to bear. While he has many cynical characters, he isn’t cynical himself, and the mores and attitudes, as much as we may cringe at them, are presented matter-of-factly. Bohemond, the other knights, the traitor Firouz — all the characters — never act like modern men in costumes. That failing has ruined many a historical work of fiction for me over the years.

Little insight is given into the Turks, which makes sense. None of the knights or pilgrims have any real knowledge of the regions or their inhabitants. They know the Turks to be as brave as they are, and are never dismissive of them in battle, but beyond that, they know nothing. The reader is put into the protagonists’ position, learning a little bit here and only a little bit there as information dribbles in from refugees and traitors. Like Bohemond, I was surprised to discover that the Turks weren’t a monolithic group, but one with its own divisions and rivalries.

Seven hundred years or so after they failed, there’s still tremendous debate about the Crusades and the motivations of their participants. Some historians have claimed that they were no better than pirate raids against the East. Others have said that they were a way for the pope to direct the violence endemic to Europe after the fading away of Charlemagne’s empire. Others yet suggest that the effort to liberate the Holy Land from Muslim domination and restore Christian rule was honest.

Duggan’s depiction of the Crusade shows both honest and dishonest motives. Several of the lords make it clear that they will remain with the crusade long enough to liberate Jerusalem and attend mass in the Church of the Holy Sepulchre, which is what they do. Others declare that they will seek some sort of domains of their own in the East. Bohemond, with his eyes on the mighty fortress city of Antioch, is the most ambitious of these men.

Whatever the truth, in 1071 at the Battle of Manzikert in the far eastern reaches of Anatolia, the Byzantine Empire was dealt a tremendous defeat by the army of the Seljuk Turks. In the next few years, most of the manpower-rich region had fallen under the Seljuk’s banners. The Empire feared it could no longer hold the line against Muslim expansion and that the heart of their realm, and Constantinople itself, was at risk.

In 1095, the Byzantine emperor, Alexius, took the drastic step of appealing to Pope Urban II for help. Despite the official schism between the Roman and Greek churches, the emperor hoped a wider sense of Christian brotherhood would lead to aid from the West. It did, but not in the way Alexius expected. All he wanted were mounted mercenaries to replace his lost forces; instead the pope issued a call for pilgrims to travel to the Holy Land and take Jerusalem from the infidels. Within a year, several forces of untrained pilgrims and knightly lords with their retinues set off for the East.

Finally, there are the battles. As much as the Crusade involved political maneuvers, it involved battle. Duggan delivers them succinctly and clearly. In addition to actual scenes of combat, he provides a thorough explanation of the preparation that goes into each battle and siege. For one not already knowing the history and the real battles’ outcomes, there are moments of tremendous tension as lines of knights charge the Turks or soldiers make mad dashes for safety. Yet as exciting as they are, the battles aren’t the heart of the book.

Count Bohemond is about the rise of a man of great talents and desires to his full stature during a pivotal period in Western history when Christendom actually united, if only briefly, and attempted to turn back several centuries of steady defeat. Duggan’s Bohemond serves as a window into this violent and chaotic time.

This book may not have as high a quotient of action as the crusader tales of great writers such as Harold Lamb or Robert E. Howard, but it is nearly as colorful and one I enjoyed equally as much. If you have the slightest interest in the period, find yourself a copy.

On a final note, until recently I didn’t read all that much historical fiction. Now I’m reading lots of it (I’ve just started Harold Lamb’s terrific Swords from the West and I’ve got Bengtsson’s The Long Ships on my TBR pile). I’m hoping to pick up cheap copies of other books by Duggan. My dad, on the other hand, was a big fan. This was one of his books that I dug out of the boxes in the attic. He would’ve turned 85 last Saturday. So thanks, Dad. And happy birthday!

And I wonder why my to-be-read pile never seems to get any smaller …

Looks intriguing. I will see if I can track it down. If you are looking for a historical fiction recommendation I suggest “The Religion” by Tim Willocks.

@ Joe H – ain’t it the truth

@ K Lizzi – There are cheap copies out there and Cassell Military Press reissued most of his books a few years ago.

That’s the second recommendation for Willock’s book I’ve heard. It looks like a lot of fun.

Sounds great.

And, of course, I second ‘The Religion.’ 😉