A Contemporary Eye on the Pulps: Fantasy Review, April-May 1949

Recently I’ve found myself thoroughly captivated by early fanzines. I’m not doing a study by any means… I’m just surfing eBay, picking up bargains here and there. And I have to say I’ve been lucky enough to stumble on some marvelous finds.

Recently I’ve found myself thoroughly captivated by early fanzines. I’m not doing a study by any means… I’m just surfing eBay, picking up bargains here and there. And I have to say I’ve been lucky enough to stumble on some marvelous finds.

Each of the fanzines I’ve found has its own unique identity, but there are things they all seem to have in common. For one thing, they are suffused with a marvelous optimism. Science fiction of the 1930s and 40s wasn’t dominated by grim dystopias like The Hunger Games and The Matrix; often it idealized the future, as in Things To Come (1936), or gave us heroes like Buck Rogers. It’s hard to be gloomy when the future is whispering promises of ray guns and a personal jet pack.

But it was more than just that. Immerse yourself in early fandom long enough, and you’ll come to see that interest in science fiction was viewed unquestionably as a virtue, like temperance and personal hygiene. Never mind that society viewed SF as perhaps the lowest form of literature, low-grade children’s entertainment at best; early fans were convinced otherwise, and by the late 40s there was actually evidence to support that line of thinking. SF prepared you for the future, and in a world still startled and horrified by the rapid advances of World War II — and thrown headlong into the Atomic Age by the bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki — preparation of any kind offered a psychological edge, even if just an illusory one, and fans relished the vindication.

Now, I have no doubt that readers of the day were drawn to the pulp magazines by the same things that drew me, decades later: bright covers featuring monsters, dinosaurs, space ships and beautiful women. But the pages of early fanzines are filled with earnest young fans patting each other on the back for their enlightened choice in literature, as if reading science fiction was the vocation of a select elite who took on the task as a social imperative, like early socialists. All while simultaneously expressing giddy excitement at the latest installment of their favorite space opera. It’s funny, and oddly charming, and it doesn’t hurt that many of the fans filling the pages of these slender proto-magazines are fine writers in their own right — and many of them are insightful critics, as well.

[Click on any of the images in this article for larger versions.]

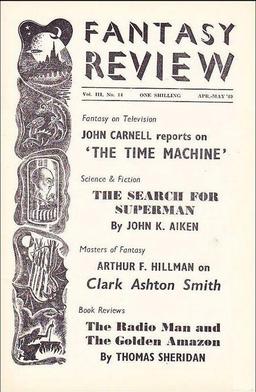

Today I’d like to talk about Fantasy Review/Science-Fantasy Review, a high-quality British fanzine edited by Walter Gillings. Eighteen issues appeared between March 1947 and Spring 1950, when Gillings was hired as editor of Science Fantasy, one of the leading British SF magazines. To be honest I’d never even heard of Fantasy Review until I came across a bundle of issues on eBay. Curiosity got the better of me, and I took a chance.

I’m glad I did. The issues I purchased are packed with well written reviews, columns and opinion, and plenty of discussions on the state of fantasy. Writers include Forrest J. Ackerman, Thomas Sheridan, John K. Aiken, Kenneth Slater, and many others, and the list of Associate Editors on the masthead reads like a Who’s Who of British fandom: John Carnell, J. Michael Rosenblum, Arthur F. Hillman, Fred C. Brown, and A. Vincent Clarke. David Kishi, Forrest J. Ackerman, Sam Moskowitz, and Bob Tucker are listed as American Correspondents. For a student of the genre — or anyone interested in classic fantasy, really — these issues are a delight.

There’s too much here to cover in one article, so let’s focus on a single issue: April-May 1949 (#14). The cover promises John Carnell’s report on the new film The Time Machine, John K. Aiken on “The Search for Superman,” Arthur Hillman’s entry in the Masters of Fantasy series (on Clark Ashton Smith), and a batch of reviews by Thomas Sheridan.

Aiken’s Superman article was the first to really catch my attention. Here we get an undiluted jolt of the optimism of fandom — that raw and unshakable faith in science fiction as the answer to a host of the world’s ills:

What is going to happen to Homo Sapiens? In its purely physical sense this question must be daily in the mind of everyone who reads or listens to the news. Atomic war, catastrophic food shortage, rising population, exhaustion of coal and oil in the industrial and military scramble: will Man be able to extricate himself from the mess he has gotten himself into? These are the questions which frighten us into reading science fiction. And there, of course, we find innumerable answers.

It gives me a rather peculiar thrill to be quoting Mr. Aiken in the year 2014 — and on a paperless, global computer network, to boot. We are very much the inhabitants of a science fiction future, peering back through the decades at his column.

I think he would have liked that. Although, perhaps, he’d be disappointed we aren’t doing it from Venus.

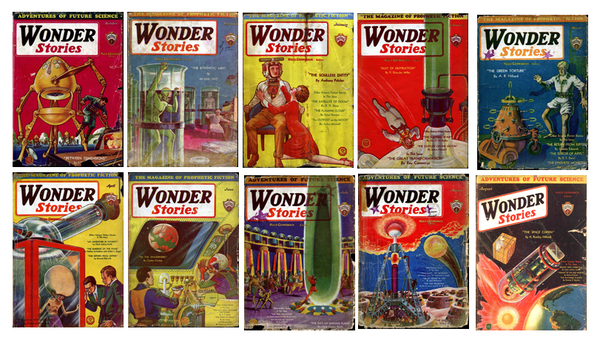

Even more interesting is Thomas Sheridan’s critical look back at the early days of Hugo Gernsback’s Wonder Stories: “The Story of Wonder: The Days of Depression,” which ignited my interest in early 30s pulp SF all over again.

“The Magazine of Prophetic Fiction” has other things to worry about in those troubled times. Its size for one thing; its price, for another. After 18 months of slow progress, it had made a mistake which almost proved its undoing. In abandoning the large size which distinguished both it and Amazing from the new Astounding, at the end of 1930, it claimed to have taken a reader’s survey which plumped for the “more convenient” size of the general run of pulps…

These 1931, small-size issues were hardly impressive on any score. Though Paul’s covers were ever present, there were not always up to his usual standard… As for the stories, apart from the introduction of Clark Ashton Smith and John Beynon Harris, it was a pretty dull period, relieved only by the continued collaborations of Nathan Schachner and Arthut Leo Zagat — eg. “Exiles of the Moon” (Sept – Nov.) — and “The Time Projector” (July-Aug.) in which Dr. Keller combined with Editor David Lasser. Unless your taste ran to the Interplanetary Police and future gangster stories of oldster R.F. Starzl, or the steady progression of Otfrid von Hanstein’s “Utopia Island” (May-June) there was little to commend and a good deal to criticize in “The Reader Speaks.”…

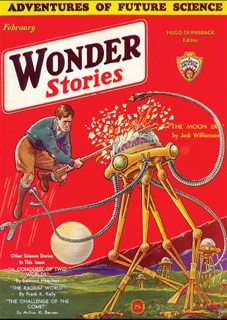

With the Nov. ’31 issue came a return to the large size… At the same time, the contents improved… Among the newcomers were John W. Campbell and his Astounding star of later years, Clifford D. Simak. While Smith continued his florid fantasies, Jack Williamson returned to favour with “The Moon Era,” in the same (Feb. 1932) issue which presented Edmond Hamilton’s “A Conquest of Two Worlds,” ever since lauded even by those who consider his work unpraiseworthy. Meantime, John Taine’s “The Time Stream” (Dec. 1931 – Mar. 1932) was being serialized…

Wonder Stories, 1930 -1931 (click for bigger version)

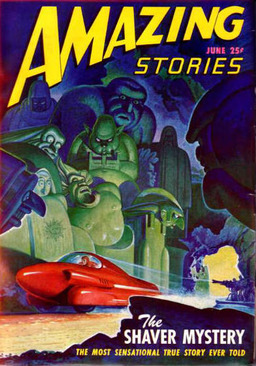

Next is the Among the Magazines, in which Kenneth Slater bids a not-so-fond adieu to Richard Shaver’s Shaver Mystery in a column titled “Goodbye to All That! Readers Vote on the Shaver Mystery.”

Next is the Among the Magazines, in which Kenneth Slater bids a not-so-fond adieu to Richard Shaver’s Shaver Mystery in a column titled “Goodbye to All That! Readers Vote on the Shaver Mystery.”

Richard Shaver, a man who managed to significantly boost Amazing‘s circulation in the 40s with his intricately detailed “true tales” of Satan’s henchmen, sinister subterranean Dero, beautiful kidnapped women, and the lost civilization of Lemuria, went to the grave proclaiming his stories were true. And for him, perhaps they were — from a modern viewpoint there’s ample evidence that Shaver was a paranoid schizophrenic, simply trying to cope with his delusions the best he could.

But for fans desperate for their beloved genre to earn some scraps of respect — and for Amazing Stories to return to its former glory — the Shaver Mystery was a prolonged nightmare, as Slater makes clear in his comments:

At long last the infamous Shaver Mystery is finished — as far as Amazing Stories, which started it, is concerned. Having dropped it, Editor Palmer took a reader’s poll on whether to take it up again, and although there were only six votes against it no more than 132 plumped for reviving the whole business. As RAP very justly points out in the April issue, it would need “a great many more letters to bring it back — say 75,000.”… So that, dear friends, is that!

If you’re interested in more on the Shaver Mystery, our own James Maliszewski addressed the topic in his joint review of War over Lemuria, and the Palmer bio The Man From Mars.

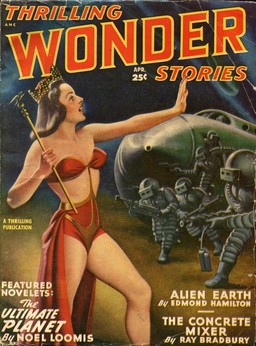

Slater eventually moves on to more wholesome topics, including other pulp mags from 1949. He covers the new Super Science Stories, the March issue of Science Fiction, and the latest issue of the new incarnation of Wonder Stories, Thrilling Wonder, now edited by Sam Merwin:

The cover of Thrilling Wonder‘s April issue illustrates Ray Bradbury’s “The Concrete Mixer,” with Miss California of 1963 (suitably undressed) hailing invading Martian hordes. His constant depicting of mankind as perfectly beastly must be one of the reasons for Bradbury’s popularity, but I’m getting a little tired of being told an obvious truth — especially when it applies to you and me! The lead novel is “The Ultimate Planet,” in which Noel Loomis apparently seeks to prove that scientific upbringing is not the answer to everything. Maybe there’s a sequel in the offing, but the ending is far from satisfactory.

In “Alien Earth,” Edmond Hamilton spares us his famous Menace and takes us into a weird world where everything moves so slowly that we can see the vines and creepers fighting for survival; but it moves fast enough to be enjoyable…

Among the seven shorts, Murray Leinster’s “The Lost Race,” which has at least two plots, is very good; Fredric Brown, though stuck for one, is highly amusing with “All Good Bems”; and Rog Phillips’ pink rabbits from Venus add to the humour in “Quite Logical.” Leigh Brackett, Raymond Z. Gallun, Margaret St. Clair and James Blish are also present. Next (June) issue brings Brackett’s “Sea Kings of Mars”…

But I think perhaps the best article in this issue of Fantasy Review is Arthur F. Hillman’s appreciation of Clark Ashton Smith, in his Masters of Fantasy column “The Poet of Science Fiction.”

Like Thomas Sheridan’s “Story of Wonder” column above, this one made me ache to dig up moldering copies of Wonder Stories and experience these stories for the first time, in their original setting.

“The Ninth Skeleton,” the first of his work to appear in Weird Tales (Sep. 1928), gave little indication of the genius which had yet to flower. His rare and brilliant imagination was not used to the narrow confines of story-telling, and for a time he found the strictures irksome. Not until the May 1930 issue did he appear again in the same magazine with “The End of the Story,” whose title proved a misnomer; it was only the beginning of the story of a great writer of fantasy.

Set in the haunted regions of Averoigne, in the France of the Middle Ages, the abode of vampires and warlocks, of lamia and tempting succibi, it drew freely on the fear and mysticism rampant in those times. But the ingenuity of the plot was overshadowed by the colour, depth, and erudition of the language… This success started him on a cycle of similar stories, of which the next, “A Rendezvous in Averoigne (Apr. 1931) was even more colourful and beautifully written than the first. But by then Smith’s work had already taken a significant turn; he was writing science fiction, and for a different market…

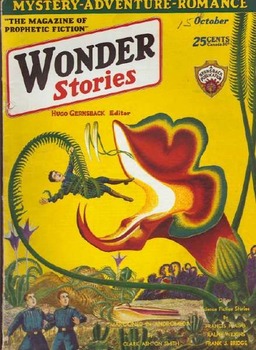

Though Hugo Gernsback has been given ample credit for the encouragement he gave to many early science fiction writers it is sometimes forgotten that Clark Ashton Smith was among his protégés. “Marooned in Andromeda,” which appeared in Wonder Stories (Oct. 1930), was his first work of this kind; and it stood out strongly among the amateurish efforts that hampered the progress of this new type of popular literature… In “Andromeda,” the reader plunged with Captain Volmar and his crew into depths of space where far-strewn nebulae spanned complete emptiness; and even when three mutineers of the ‘Alcyone’ were cast adrift on a bizarre world, the human element was reduced to a minimum. With a solemn respect for the cruel hardships of alien surroundings, the author maintain a wholesome disregard for humanity and is petty moralities. The sequel, “The Amazing Planet” (Science Wonder Quarterly, Summer 1931) showed Captain Volmar, once more united with his erring companions, engaged in further struggles with monstrosities such as only Smith’s imagination could devise.

Of mechanistic concepts, however, little may be found in all his science fiction. Ray-guns, tractor-beams, McMillan projectors, Bergenhom space-drives, and the scientific mumble-jumbo of later writers are as rare as the reporter hero, mad scientist and beautiful daughter of a less complicated decade. Atmosphere is Smith’s forte, even action being subordinated to this main element, though when necessary he can urge his story along with the best of the hustling school. Generally, he followed the dictum of his colleague Lovecraft in his “Notes on Interplanetary Fiction” and practiced what he preached himself concerning the raising of science fiction’s literary standards and the danger of too much “realism” being introduced into the medium.

I wrote a brief appreciation of Clark Ashton Smith after reading “The Vaults of Yoh-Vombis” in November — and if you’re at all interested in Smith, I highly recommend Ryan Harvey’s epic four-part The Fantasy Cycles of Clark Ashton Smith series, starting with The Averoigne Chronicles, and Matthew David Surridge’s 2012 article “A Few Words on Clark Ashton Smith.”

I wrote a brief appreciation of Clark Ashton Smith after reading “The Vaults of Yoh-Vombis” in November — and if you’re at all interested in Smith, I highly recommend Ryan Harvey’s epic four-part The Fantasy Cycles of Clark Ashton Smith series, starting with The Averoigne Chronicles, and Matthew David Surridge’s 2012 article “A Few Words on Clark Ashton Smith.”

This issue of Fantasy Review wraps up with a news column, a lengthy review section (covering Ralph Milne’s The Radio Man, Jack Williamson’s Darker Than You Think, Roads by Seabury Quinn, L. Sprague de Camp’s The Wheels of If, and others), assorted ads (including a half-page ad for Arkham House), a Letters Column, and assorted classified ads.

Fantasy Review was edited by Walter Gillings and published in the UK. The April-May 1949 issue is 32 pages, priced at one shilling.

Finally, if you’ve read this far, congratulations for your perseverance, and for your obvious love of old fanzines. I bought the collection of 22 issues (at left) on eBay earlier this month. If I’d know a little more about Fantasy Review, I would have known there weren’t 22 issues — and sure enough, when it arrived I discovered that most of the issues in the lot were duplicates. There were six copies of the Autumn 1949 issue, for example.

I could sell them, but since I paid $36 for the lot — or only slightly more than a buck an issue — it doesn’t seem worth my time. I’d rather give them away. So here’s my offer: if you’re interested in old fanzines, and willing to jot down a paragraph or two of your thoughts after you read one, I’m happy to send you a copy. Just send me an e-mail (to john@blackgate.com) with the subject “Fantasy Review” (and a US address, please), and I’ll send one your way, media mail. I’ll compile any responses I get into a future post.

Quantities are limited (I have about a dozen duplicates), so act fast. The usual caveats: Terms subject to change. No purchase necessary. Offer may be voided at any time, including retroactively.

This is the third vintage fanzine I’ve discussed here; I started with The Fantasy Fan (1933-1935) and Robert A. Collins’ 1980-era Fantasy. Both were excellent, and I’m happy to add Fantasy Review to that esteemed list.

Though not incredibly attracted to the original pulps, I get where you’re coming from here John.

Collecting old Dragon Magazines (I’m four issues shy of owning the first one hundred) is a thrill to me not just because of the nostalgia (several years of the magazine actually pre-date my acquaintance with the RPG hobby) but also because you can get a sense or feel of what it must’ve been like for the original readers of the mag.

There’s something to be said for this sort of historical immersion with an artifact.

James,

Indeed! I collect early issues of Dragon — although my collection is nowhere near as complete as yours! — and the sensation of reading them is very much the same. Re-reading early Dragon, I’m frequently transported right back to the earliest days of the hobby, experiencing the joy of discovery all over again — that sense of something new and exciting, that anything can happen.

I think the pulps contain a similar quanta of excitement, at least for me. The same sense of the flowering of a fabulous new thing, and the talented creators taking it in unexpected new directions.

This is closely tied in with nostalgia, of course, so I doubt you can experience it if it’s not something you thrilled over long ago. You may be immune to the joy of the pulps, but I glad we share a fascination with Dragon.

Yes. My point was that I could relate to the experience even when the material in question is something I’m not particularly interested in.

A similar experience: I once had a professor who was commissioning a fellow grad student to make xerox copies of some 18th century philosophy texts he had gotten through interlibrary loan. This student showed me in one of these books a few pages where tobacco cinders had burned through. There was a brief thrill of being transported back in time to when some 18th century reader dropped a bit of pipe ash onto his book.

I don’t think I’m communicating well the sensation of feeling some contact with an older reader. But the point is that I enjoy the experience even if I’m not particularly thrilled with the content of the book or mag.

John: “It gives me a rather peculiar thrill to be quoting Mr. Aiken in the year 2014 — and on a paperless, global computer network, to boot. We are very much the inhabitants of a science fiction future, peering back through the decades at his column.”

Yes! The same sort of reflection has certainly crossed my mind while reading similar lit (“If only they could see the smartphone I’m holding,” I think to myself).

Perhaps that’s another boon of going back, of revisiting those yellowing pages: it lifts us out of the contemporary here-and-now to better appreciate all the wonders — and terrors — of our time from that longer view.

I must admit, it annoys me just a little that Millennials don’t occasionally pause — just for one moment — from their texting and downloading of films, to drop their jaw in amazement that they are performing feats unimaginable for the first 199,980 years of the human race’s 200,000-year existence.

> This student showed me in one of these books a few pages where tobacco cinders had burned through. There was a

> brief thrill of being transported back in time to when some 18th century reader dropped a bit of pipe ash onto his book.

James,

That’s a marvelous tale – thanks for sharing that.

Carl Sagan used to say that no invention was so incredible as writing. To be able to experience an author’s thoughts, just as she imagined them, hundreds of years after she died, is an amazing thing. But words aren’t the only way experiences are shared in books down through the years, and sometime other avenues can have even more impact.

> Yes! The same sort of reflection has certainly crossed my mind while reading similar lit (“If only they could see the smartphone I’m holding,” I think to myself).

Nick,

I know! I sometimes find it a little hard to truly experience the wonder of Golden Age SF, when the tablet I’m reading it on is far more wondrous than the 23rd-century computers they’re describing.

> I must admit, it annoys me just a little that Millennials don’t occasionally pause — just for one moment — from their texting and downloading of films,

> to drop their jaw in amazement that they are performing feats unimaginable for the first 199,980 years of the human race’s 200,000-year existence.

Oh, I don’t know. Were we any better at that age? I just took my old Apple II for granted, the same way my kids take their tablets for granted. That’s the prerogative of the young: they get the most out of modern tech precisely because they are in no way intimidated by it. To them, it’s no more wonderful than the toaster.

I’m reading Fantasy Review 3:15 (Summer 1949). It retains legitimate interest beyond the nostalgia factor. For one thing, just as newspapers were for history in general, fanzines were a first draft of history — for sf and fantasy. This issue reviews books that have become recognized as classics (Ward Moore’s Greener Than You Think — reviewed here by John Beynon, i.e. John Wyndham; here’s Wyndham reviewing a catastrophe novel, and of course he himself is known as one of the great writers of sf catastrophes — also Sturgeon’s Without Sorcery, which seems to have contained a few Theodore S. stories that I’ve not yet read; and more) as well as a couple of duds. Arkham House collectors might be amused by the review of a Derleth collection composed of stories the author himself regarded as mostly mediocre (Not Long for This World). A highlight of the issue is a lengthy profile of Ray Bradbury, not yet 30 but already recognized as outstanding, his reputation within the filed firm and his career extending already into the slicks. But at this time his only book seems to have been Arkham’s Dark Carnival and a British edition thereof.

Classified ads bear witness to the well-established phenomenon of the sf and fantasy collector. British readers were mostly beholden to American magazines and books.

A very interesting time capsule, but of more than quaint interest.

SFR III:16 was an interesting issue too. One nugget of interest. It says that Arthur C. Clarke was on record in 1938 as saying that Stanley G. Weinbaum’s “A Martian Odyssey” is “the best story to put before beginners in order to convert them to the field” and that a 1945 “poll of s-f fandom” selected that story “as the most popular short story, heading a list of some 160 tales [I’d like to see that list!] in which were at least ten other Weinbaum pieces.” I wonder what the responses would be if one were, today, to poll a bunch of sf readers and ask them what story, as of 1938, ACC recommended as the gateway into sf.