Gonji: The Deathwind Trilogy by T. C. Rypel

Drift back in time to the eighties when swords & sorcery was preparing to die, at least as a force in fantasy publishing. Where once Andrew Offutt and Lin Carter as well as Robert E. Howard packed the shelves of your local B. Dalton, they were about to be crowded out by the rise of the Tolkien clones. Exciting authors like Charles R. Saunders who were leading S&S down new paths would see their heroic fiction production curtailed by sales numbers that didn’t meet publishers’ expectations.

Drift back in time to the eighties when swords & sorcery was preparing to die, at least as a force in fantasy publishing. Where once Andrew Offutt and Lin Carter as well as Robert E. Howard packed the shelves of your local B. Dalton, they were about to be crowded out by the rise of the Tolkien clones. Exciting authors like Charles R. Saunders who were leading S&S down new paths would see their heroic fiction production curtailed by sales numbers that didn’t meet publishers’ expectations.

Today, technological advancements have paved the way for the return of ancient adventurers. The internet has allowed old and new fans to find each other and connect with writers to create a camaraderie of creators and consumers. Quality print-on-demand publishing, e-books, and small presses using those tools have led to the resurrection of several heroes, including Saunders’ own Imaro and Dossouye. Another of those revived heroes is T. C. Rypel’s Gonji, a half-Japanese, half-Scandinavian warrior first introuduced thirty years ago, wandering the slopes of the Carpathian Mountains in search of a mysterious force known as the Deathwind.

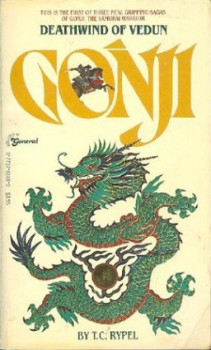

When T. C. Rypel delivered his first novel to Zebra Books back in the early eighties it was over thirteen-hundred pages long. While that’s nothing peculiar these days, back then it was seen as unprecedented and Zebra’s response was to break it up into three distinct books. Rypel’s titles for the resultant three volumes were Red Blade from the East, The Soul Within the Steel, and Deathwind of Vedun. Zebra decided to take Rypel’s third title and reassign it to the first book, then re-title the last two Samurai Steel and Samurai Conflict. Their changes provide a hint of what the publisher had in store for the books.

Instead of promoting Gonji’s adventures as heroic fantasy — peopled with alien refugees, filled with demonic scheming, and bursting with terrible battles (complete with monsters) — they slapped an Eastern dragon on the covers and marketed them as akin to the Asian-themed novels of writers like James Clavell and Eric van Lustbader that were popular at the time. In that they were sort of successful. I remember seeing them in stores and assuming they were one more Japanese-set adventure story. While my interest in heroic fiction was high, my interest in Clavell clones was exactly none and I passed them by.

There were other problems with Zebra’s handling of the books that hampered their success. Nowhere did the books indicate they were actually a trilogy, instead appearing to be standalone episodic volumes. Even though he was able to include exstensive recaps in the second and third books, Rypel recalls that reviewers at the time still expressed dismay at the non-endings of the first and second books.

Finally, Zebra didn’t list the books as heroic fiction in their catalogue. This meant genre booksellers took no interest in the books and didn’t order them. They generally turned up only in the mainstream fiction sections of stores, where their target audience was less likely to find them.

And still, Rypel experienced a fair degree of success with Gonji’s adventures. Before the whole thing fell apart, Rypel was able to write and see published another two Gonji books: Fortress of Lost Worlds and Knights of Wonder. Despite everything that was stacked against them the books remained in print for several years and sold over 150,000 copies. But when Zebra ended its fantasy titles in favor of romance titles and then his agent, who never really loved heroic fantasy, stopped marketing Gonji, the character “went into hiatus.”

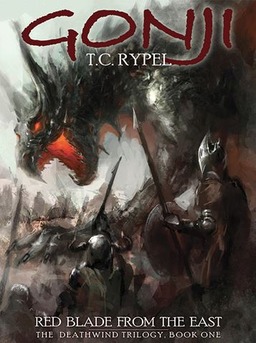

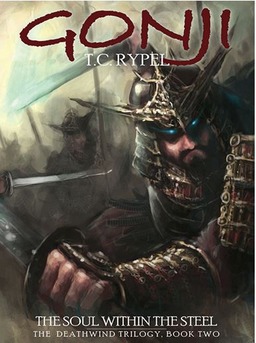

Now, thanks to the Borgo Books imprint of Wildside Press, the Gonji trilogy is back in print, both as e-books and paperbacks, Rypel’s original titles restored. The generic dragons of the old covers have been displaced by dark, impressionistic art imparting the swirling infernos of bloodshed and chaos inside. This series is now proudly presented as tales of dark swords & sorcery and each book clearly indicates it’s part of a trilogy. The fourth volume, still called Fortress of Lost Worlds, and the retitled fifth, A Hungering of Wolves, are on their way from Borgo in the near future. The reprinting of Gonji is one of the events strengthening my belief that today is as great a time for swords & sorcery as the 1970s.

Now, thanks to the Borgo Books imprint of Wildside Press, the Gonji trilogy is back in print, both as e-books and paperbacks, Rypel’s original titles restored. The generic dragons of the old covers have been displaced by dark, impressionistic art imparting the swirling infernos of bloodshed and chaos inside. This series is now proudly presented as tales of dark swords & sorcery and each book clearly indicates it’s part of a trilogy. The fourth volume, still called Fortress of Lost Worlds, and the retitled fifth, A Hungering of Wolves, are on their way from Borgo in the near future. The reprinting of Gonji is one of the events strengthening my belief that today is as great a time for swords & sorcery as the 1970s.

By now I hope you’re wondering about the books themselves. I’m generally disappointed by long fantasy books as they tend to get weighed down by side plots, slathered-on details, and neverending rosters of minor characters. Rypel avoids all those pitfalls. The focus is always on Gonji, his motivations, and where he fits into the various plots and intrigues surrounding him. While long, the books have the feel of the old Mission:Impossible credits. In the opening volume, Red Blade from the East, a fuse is lit which keeps our attention right through until the final book, Deathwind of Vedun, when it detonates in a whirlwind of battle and destruction. In between, in The Soul Within the Steel, Gonji struggles to determine his place within events, to avoid being forced to undertake terminal heroics and to stay true to his samurai ideals.

Rypel tells us just enough about Gonji in Red Blade from the East to get us hooked. Forced from his homeland of Japan by terrible events, he has come to early 17th century Central Europe in search of his destiny. As his mentor, a Shinto priest, lay dying, he told Gonji to travel to the West to find someone or something called the Deathwind. With no more useful information than that Gonji left Japan. Now several years later he has nothing to show for his time. Indeed, he seems to have allowed himself to be buffeted from place to place by whispered rumors and legends that lead to nothing.

Caught up in a battle against Imperial Habsburg forces, Gonji throws in with a band of mercenaries cobbled together from all over Europe. They tell him they are in service to the mysterious King Klann, an exile from some unheard-of land. They also follow orders from a dark wizard in service to their king. Seeing no better propsects, Gonji joins them and takes up the pledge all the mercenaries have made to the wizard’s service as well as the king’s.

Soon, though, the wizard’s demands become abhorrent as Gonji witnesses the mercenaries commiting several horrible acts. Gonji’s inherently honorable nature rebels at his companions’ despicable actions and he flees. Ultimately his path brings him back into that of the mercenaries and their lord.

From there, several unpleasant encounters direct him toward the city of Vedun. A dying monk asks him to deliver a message to someone named Simon Sardonis. Later he is too late to save a young man from death but manages to kill his tormentors. He feels obligated to return the body to its family, which turns out to be one of the most important in Vedun.

Vedun is like a mundane version of Michael Moorcock’s mystical city Tanelorn. Tucked away in the Carpathians’ heights, Vedun exists to provide respite for its citizens from the endless warfare of the age. The city is hidden from the direct sight of its more covetous neighbors, ruled by a council dedicated to peace among its citizens no matter their creeds or ethnicities, and protected by a noble lord with a strong army and powerful fortress. For years Vedun has maintained its dream of peace and even achieved a degree of prosperity. All that changes with the coming of King Klann.

Just prior to Gonji’s arrival, Vedun has fallen to King Klann. Aided by his sorceror Mord and Mord’s dark servants — a wyvern and a grotesque giant — Klann has siezed the city’s fortress, driven out its defenders, and has declared Vedun under his rule. Never seen by Vedun’s citizens, questions of Klann’s identity and why he’s come to their home form the mysteries at the heart of Red Blade from the East. Rypel’s slow reveal of those answers is masterful.

Just prior to Gonji’s arrival, Vedun has fallen to King Klann. Aided by his sorceror Mord and Mord’s dark servants — a wyvern and a grotesque giant — Klann has siezed the city’s fortress, driven out its defenders, and has declared Vedun under his rule. Never seen by Vedun’s citizens, questions of Klann’s identity and why he’s come to their home form the mysteries at the heart of Red Blade from the East. Rypel’s slow reveal of those answers is masterful.

It also sets up more questions. Answering these makes up much of The Soul Within the Steel. It’s in this voume that Gonji struggles most with where, if anywhere, he fits in with the people of Vedun, some of whom have become his close friends. He is also certain he knows the solution to the riddle of who or what is the Deathwind. Simon Sardonis, the man the monk asked him to bring a message to, appears to be a werewolf. Unwilling to risk killing innocents, Sardonis lives in hiding. Figuring a way to talk to him bedevils Gonji for much of the book. By the second novel’s end most of the mysteries have been solved, leaving the conflict between Vedun and King Klann to be settled.

In a message to me on Goodreads Rypel claimed Deathwind of Vedun

had the longest, most character-centric battle in the genre’s history.

I think he may be right. About a third of the way into Deathwind the final battle toward which everything has been leading erupts. It’s been planned for meticulously by Gonji and his compatriots yet nearly nothing goes as expected. What was hoped would be a well-executed operation to surprise and overwhelm Klann and Mord begins to suffer battlefield friction at once. Fighting begins without warning, traitors unveil secrets to the enemy and secret weapons don’t live up to their expectations. By the battle’s end, Rypel has taken us and his characters up and down almost every street in Vedun, across the fortress walls, and up every tower. For nearly two hundred pages (my e-book estimation), heroes and villains come together in an intimate fight to the finish. There is virtually no letup for the entire last half of the book (and it’s freaking awesome!).

I think Rypel has written the final battle as an epic created by a miniaturist. Instead of giving us the movement of vast armies we get duels between individuals. The battle isn’t fought on great, open plains but in the narrow confines of back alleys, its outcome depending on the results of numerous small actions. There is a training section in Soul Within the Steel that I felt went on for too many pages, but upon reading Deathwind I realized it doesn’t. First, it establishes the skills of the citizenry and makes their fights against experienced mercenaries plausible. More importantly, it provides time to give the minor players more than just names, it gives them depth. When the battle starts there are dozens of charcters with specific tasks set to them by Gonji and his colleagues. My concern over their success or failure was demonstrably heightened by Rypel’s work defining them before the battle.

Rypel’s greatest achievement in these books is Gonji. There is plenty of fighting and adventuring in Red Blade from the East, but I was surprised, first, with how much of the book was taken up with Gonji thinking through his life or talking to someone. Then I was surprised that I wasn’t bored by that. These books are heroic fantasy and a high action quotient is expected in the genre. A high introspection quotient, not as much.

Rypel’s greatest achievement in these books is Gonji. There is plenty of fighting and adventuring in Red Blade from the East, but I was surprised, first, with how much of the book was taken up with Gonji thinking through his life or talking to someone. Then I was surprised that I wasn’t bored by that. These books are heroic fantasy and a high action quotient is expected in the genre. A high introspection quotient, not as much.

In an earlier review of Red Blade I stated that:

There are great scenes of action in Red Blade from the East but they’re not the focus of the book. Much of the book revolves around Gonji struggling to forge a place for himself in Europe. Half-caste and moulded by the honor traditions of Japan, he’s rarely at ease. Too often he’s succumbed to compromises that would have required his suicide in the past. He’s constantly torn [between] events, a desire to survive, and his search for his destiny alongside the Deathwind. Gonji desires to be noble and heroic, but events and a willingness to compromise have made it an ongoing struggle. Rypel’s created a character of admirable depth and introspection, things often lacking in S&S.

As the action increases and the tension is ratcheted up in Soul Within the Steel, Gonji’s personality is exposed even more. I suspect some readers might be put off by that description, but please don’t be. Gonji is first and foremost a warrior struggling to stay true to a code of honor from which he has drifted away during his journey into the West. Gonji’s no mopey, emo-kid. He’s a hero. For all his claims to the contrary, Gonji’s a hero. He’s educated and taught to understand the consequences of his actions. What will happen to the city, and more importantly the people of Vedun should he lead them into battle, creates great hesitancy in Gonji. In less skilled hands than Rypel’s all this pondering could be deadly, snapping any narrative drive into pieces. Instead, it breathes life into a man made of ink and fools us into caring about him and what he does.

I have a pretty extensive knowledge of heroic fantasy but I didn’t know that Gonji belonged to the genre until Joe Bonadonna gave the books praise on Black Gate a year and a half ago. For over twenty years these books were basically lost to fans of swords & sorcery. I’m extremely grateful that that’s been corrected.

These look really interesting. I will be finding copies of these soon.

Fantastic review, Fletcher! (And thanks for the kudos, too!) I am very happy that you found your way to Gonji and enjoyed these classics as much as I did.

@ Glenn – They’re really solid, walking a line between the S&S of old and the big action series like Malazan

@ J Bonadonna – Thanks! Got to give credit where it’s due.

[…] Gonji: The Deathwind Trilogy by T. C. Rypel […]

[…] in January, I reviewed the first three books of T. C. Rypel’s Gonji series. Though thirty-odd years old, the books […]

[…] whims of the publishing industry and an agent who wasn’t a big heroic fantasy fan. My earlier review of the first three Gonji books, collectively called the The Deathwind Trilogy, contains a more […]