A History of Godzilla on Film, Part 3: Down and Out in Osaka (1969–1983)

Other Installments

Other Installments

Part 1: Origins (1954–1962)

Part 2: The Golden Age (1963–1968)

Part 4: The Heisei Era (1984–1997)

Part 5: The Travesty and the Millennium Era (1996–2004)

Addendum: The 2014 Godzilla

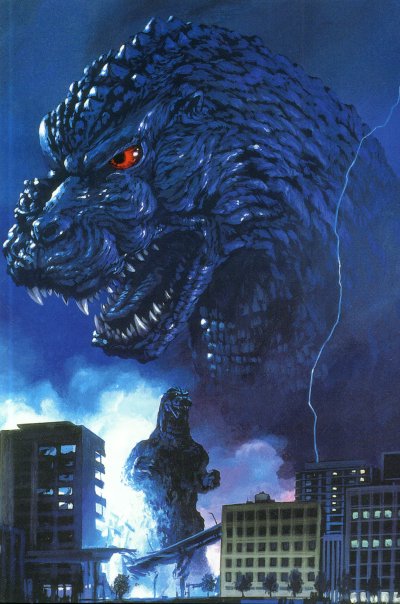

Sayanora, Tsubaraya — and Sayanora, Golden Age of Japanese Cinema

The end of the Golden Age of Japanese Giant Monster movies coincided with the end of the most productive era for the Japanese film industry. Starting in the early 1950s, the country’s film industry experienced a meteoric rise. The major studios released a combined average of 450 movies to theaters each year. But the growth of television in the 1960s started to erode film attendance. In the late-‘60s, audience levels dropped precipitously, numerous theaters closed, and the studios faced cutbacks. Contract directors and stars were released, departments were scaled down or eliminated, and the studio responsible for the “Gamera” and “Daimajin” films, Daiei, was forced out of business entirely.

Science-fiction and monster movies had it particularly rough because of the growth of television. Popular superhero TV shows offered a cheaper alternative for young audiences to get their giant monster fix. The children who increasingly made up the viewership for Godzilla movies could now see kaiju action daily from their living rooms.

Ironically, the person most responsible for the growth of SF television was Eiji Tsubaraya, Toho Studio’s master of visual effects and one of the four “Godzilla Fathers.” Tsubaraya formed his own independent company, Tsubaraya Productions, in 1963 to create special-effects television programs. The 1966 hit show Ultra Q led to the monumental success of Ultraman the next year. Each week, Ultraman pitted its giant-sized title hero against a new monster. Clone shows sprouted everywhere, and the monsters of cinema screens started to bring in less money.

In January 1970, Eiji Tsubaraya died. Minoru Nakano, one of Tsubaraya’s protégées, recalled: “I respected him so deeply. My world was Eiji Tsubaraya. He was that important. When he died, I didn’t know how to live.” It seemed Japanese science-fiction films didn’t quite know how to live after Tsubaraya’s death either, although they struggled on. Toho shut down its once legendary Special Effects Department, the place where Tsubaraya once ruled over a kingdom of fantasy films. In its place was a smaller unit with restricted budgets. The Godzilla series continued, but at only a fraction of its former splendor.

Children and Hallucinogens: All Monsters Attack (1969) and Godzilla vs. Hedorah (1971)

Toho’s vow to conclude the Godzilla series with Destroy All Monsters lasted for only six months. No artistic drive lay behind the decision to make another film: Toho brass saw a way to make an inexpensive movie to appeal to children, an idea borrowed from Daiei Studio’s Gamera movies. The Gamera films recycled footage from earlier outings to pad the running time, and aimed at young children with a monster who gets buddy-buddy with kids. Toho lifted the formula and applied it to Godzilla with All Monsters Attack. (Very long discourse on this movie here.)

Toho couldn’t quite envision transforming Godzilla into a “friend to all children” like Gamera, so with All Monsters Attack (originally released in the U.S. as Godzilla’s Revenge) they instead took Minira, the adorable mini-Godzilla from Son of Godzilla, and made him the imaginary friend of a lonely boy.

In an unusual departure, All Monsters Attack occurs in the “real world”: the monsters are creatures from movies that appear in the imagination of the boy Ichiro, who learns lessons about bravery from Minira while the two watch Godzilla on Monster Island face different foes — all re-used footage from Ebirah, The Horror of the Deep and Son of Godzilla, plus heavy borrowing from Destroy All Monsters. Eventually, Ichiro takes the lesson of watching Minira stand up against a bully monster named Gabara (new footage, thankfully) and uses it in the waking world against kidnappers. Essentially, it’s a kaiju-flavored version of Home Alone.

In an unusual departure, All Monsters Attack occurs in the “real world”: the monsters are creatures from movies that appear in the imagination of the boy Ichiro, who learns lessons about bravery from Minira while the two watch Godzilla on Monster Island face different foes — all re-used footage from Ebirah, The Horror of the Deep and Son of Godzilla, plus heavy borrowing from Destroy All Monsters. Eventually, Ichiro takes the lesson of watching Minira stand up against a bully monster named Gabara (new footage, thankfully) and uses it in the waking world against kidnappers. Essentially, it’s a kaiju-flavored version of Home Alone.

All Monsters Attack again had classic SF director Ishiro Honda behind the camera. Despite the low budget, the movie gave Honda an opportunity to film scenes of ordinary lower-middle class life in Tokyo. According to many of his acquaintances, Honda always wanted to film intimate human dramas similar to those of director Yasujiro Ozu. The real world setting of All Monsters Attack gave him the chance to do that in a Godzilla film. It was also the only monster movie on which Honda personally supervised the visual effects scenes (with the help of Tsubaraya’s former assistant Teruyoshi Nakano). Although Tsubaraya received final credit as Special Effects Supervisor, he was already too ill at the time and did no actual work on the movie.

There are moments of dramatic worth in All Monsters Attack, and it works as a child’s introduction to Godzilla. But as a genuine monster film, it’s a pale entry in the series, with far too much time spent re-hashing the fights from two earlier, much better, movies.

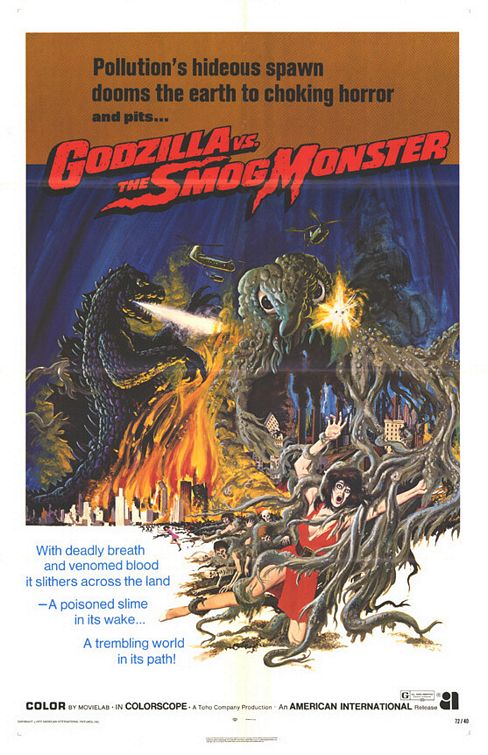

“Pale” is the last word to describe the next movie, Godzilla vs. Hedorah (long discourse here). Until Godzilla Final Wars in 2004, this was the strangest Godzilla movie of all. Better known in the U.S. under the title AIP gave it for its stateside release, Godzilla vs. The Smog Monster, the film attempted to return to serious allegorical themes. This time, instead of atomic power, the boogeyman is pollution, which was a headline-making issue in Japan in 1970. However, Godzilla is now the hero (and for the first time, unquestionably a superhero, coming at humanity’s call for help), and the sludgy ooze creature Hedorah stands in for humanity’s myopic destructive impulses.

Godzilla vs. Hedorah is sometimes horrific, with visuals of people rotting away to skeletons from Hedorah’s power, and a sequence where the monster’s slimy tendril kills an entire nightclub. But these are the exceptions in what is otherwise a psychedelic pop-art kids’ movie, complete with animated bumpers, letters from school children read over montages of pollution, blaring rock music, and Godzilla learning to fly using his radioactive fire-breath as a jet. “We made Godzilla fly in that movie,” special effects director Nakano remembers. “That was outrageous, we probably shouldn’t have done that … Looking back, the movie seems kind of crude and heavy-handed.” He probably should’ve added “kind of stoned.”

Godzilla vs. Hedorah is sometimes horrific, with visuals of people rotting away to skeletons from Hedorah’s power, and a sequence where the monster’s slimy tendril kills an entire nightclub. But these are the exceptions in what is otherwise a psychedelic pop-art kids’ movie, complete with animated bumpers, letters from school children read over montages of pollution, blaring rock music, and Godzilla learning to fly using his radioactive fire-breath as a jet. “We made Godzilla fly in that movie,” special effects director Nakano remembers. “That was outrageous, we probably shouldn’t have done that … Looking back, the movie seems kind of crude and heavy-handed.” He probably should’ve added “kind of stoned.”

First-time director Yoshimitsu Banno crafted the film without much interference from producer Tomoyuki Tanaka, who was hospitalized during most of the production. When Tanaka got out of the hospital, he was not pleased with Godzilla vs. Hedorah. Nakano recollects that Tanaka told Banno, “You ruined the Godzilla series!” Banno never directed another movie.

Despite Tanaka’s dislike for it, Godzilla vs. Hedorah is sort of terrible and wonderful at the same time. It’s admirable to see an attempt to give the Godzilla series real-world relevance again, and the many unusual asides and colorful deviations show great imagination at play. But the filmmakers didn’t have the skill or the budget to balance relevancy with child-friendly fun. Still, nobody could argue they achieved their goal of creating something different within the series.

Bugs at the Bottom of the Barrel! Godzilla vs. Gigan (1972) and Godzilla vs. Megalon (1973)

Tanaka pushed the Godzilla series “back on track,” and ended up creating two of the worst entries. Although they returned to the standard monster and alien-invasion action familiar from the 1960s, Godzilla vs. Gigan (first released to the U.S. as Godzilla on Monster Island) and Godzilla vs. Megalon are so cheap-looking and crammed with stock footage that they are often embarrassing to watch. Only younger fans who haven’t seen earlier entries in the series can find non-ironic enjoyment in either film. People who make fun of Godzilla movies in general are actually making fun of these movies specifically.

Considering that director Jun Fukuda had helmed two fine Godzilla pictures before, it’s hard to put the blame on him for why these films fail spectacularly. So much else is wrong: second-tier casts, rushed scripts, and production poverty in both the human and special-effects scenes. But the endless stock footage is the most crippling fault. The recycled scenes are obvious even to someone who has never seen any other Toho monster film: the quality of the footage, the color of the sky, and even the monster suits change jarringly from shot to shot. Using stock footage was not something Teruyoshi Nakano, who succeeded Tsubaraya as head of special effects, wanted to do: “Of course it hurt me when I had to re-use those scenes, but there was no other way — we did not have the time or the money.”

Godzilla vs. Gigan sets up a tag-team confrontation between monsters: Godzilla and Anguirus on one side, and on the other King Ghidorah and new monster Gigan. Alien invaders who look like cockroaches but wear the outer appearance of dead Japanese businessmen have an evil plot to conquer the world that revolves around a children’s amusement park. Some nondescript characters, including a comic book artist and a pseudo-hippie who always carries a corncob for some reason, help stop the nitwit aliens while the monsters fight each other and loads of re-used footage from every Toho special effects film ever made.

Godzilla vs. Gigan sets up a tag-team confrontation between monsters: Godzilla and Anguirus on one side, and on the other King Ghidorah and new monster Gigan. Alien invaders who look like cockroaches but wear the outer appearance of dead Japanese businessmen have an evil plot to conquer the world that revolves around a children’s amusement park. Some nondescript characters, including a comic book artist and a pseudo-hippie who always carries a corncob for some reason, help stop the nitwit aliens while the monsters fight each other and loads of re-used footage from every Toho special effects film ever made.

Gigan is the movie’s one bright spot. The spiky cyborg creature with the hook hands and buzz-saw chest turned into a fan-favorite and eventually snagged a major role in Godzilla Final Wars. The returning monsters fare worse: Godzilla is literally falling apart on camera (this was the fourth movie in a row using the same suit) and the King Ghidorah costume should’ve received a serious scrubbing before photography started.

The villains in the next film, Godzilla vs. Megalon, aren’t actual bugs, but they do send a big bug to handle their dirty work: the giant beetle Megalon. Or what passes for a giant beetle, but is one of the saddest looking man-in-a-monster suits Toho ever designed. Megalon looks nothing like an insect — just compare it to the Kamacuras in Son of Godzilla and you’ll see how far the effects-work plunged in six years. Similar to everything else in the movie, Megalon appears on loan from the set of one of the later Ultraman shows.

Increasing the look of a television program is Jet Jaguar, a friendly robot made from a wetsuit and the grill of a ‘50s Mustang. Jet Jaguar definitely comes from the Ultraman school of superheroes, and he can conveniently grow to 50 meters tall so he can take on Megalon and Megalon’s evil pal, Gigan (who appears for the flimsiest reasons and provides an excuse to lift footage from Godzilla vs. Gigan — again and again and again). It comes as something of a relief that most of the story centers around Jet Jaguar, with Godzilla arriving only for the climax, because Jet Jaguar functions better as a kiddie hero. The less Godzilla is made to look ridiculous, the better.

Increasing the look of a television program is Jet Jaguar, a friendly robot made from a wetsuit and the grill of a ‘50s Mustang. Jet Jaguar definitely comes from the Ultraman school of superheroes, and he can conveniently grow to 50 meters tall so he can take on Megalon and Megalon’s evil pal, Gigan (who appears for the flimsiest reasons and provides an excuse to lift footage from Godzilla vs. Gigan — again and again and again). It comes as something of a relief that most of the story centers around Jet Jaguar, with Godzilla arriving only for the climax, because Jet Jaguar functions better as a kiddie hero. The less Godzilla is made to look ridiculous, the better.

Godzilla vs. Megalon concludes with a four-way battle non-royale shot on an almost empty soundstage containing a few low hills and a wrinkled sky backdrop. Godzilla performs his silliest maneuver ever, a flying double leg kick that swings him horizontal along the ground, and at the finale he chummily shakes hands with Jet Jaguar. It’s sad.

There’s one upside: although a backhanded compliment, Godzilla vs. Megalon did make for an excellent episode of Mystery Science Theater 3000.

The good news is that Toho couldn’t possibly make the movies any cheaper than this, and the poor box-office of Godzilla vs. Megalon shook up the executives enough that for the last two movies of the Showa series, they increased the budget and let Godzilla end the era on a relatively high note.

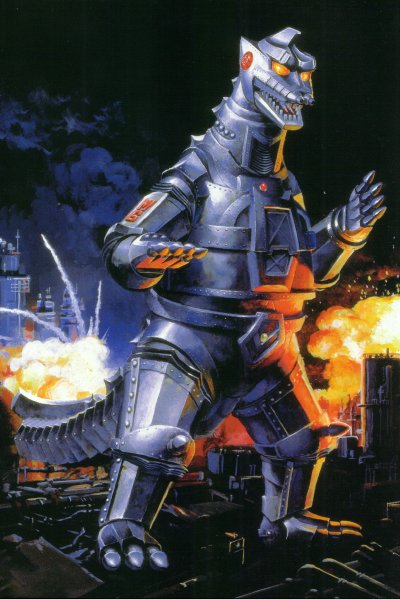

The Mechagodzilla Duology (1974–1975)

Godzilla vs. Mechagodzilla (1974) is an average monster movie that repeats the stock alien invasion plot yet again (with a dose of the costuming from the Planet of the Apes series). But compared to the previous movies it stands tall: improved production values, a minimum of stock footage, familiar faces in the cast, no annoying kids, a jazzy score from Masaru Sato, and a spectacular new monster villain.

Godzilla vs. Mechagodzilla (1974) is an average monster movie that repeats the stock alien invasion plot yet again (with a dose of the costuming from the Planet of the Apes series). But compared to the previous movies it stands tall: improved production values, a minimum of stock footage, familiar faces in the cast, no annoying kids, a jazzy score from Masaru Sato, and a spectacular new monster villain.

Mechani-Kong from King Kong Escapes inspired the creation of Mechagodzilla. This alien-constructed robot mockery of the Big-G provides great on-screen spectacle with its numerous offensive and defensive gizmos. As a concept, it doesn’t make any sense for the aliens to build a robot duplicate of Godzilla, but these aliens have a poor sense of planning. We never even discover what their grand invasion scheme is. Oh well, it doesn’t matter: Does Mechagodzilla look cool? Okay, send it out!

There’s another new monster in the mix, a protector of the Okinawan royal family named King Seesar. Designed to resemble a lion statue from Okinawan shrines, King Seesar has an interesting appearance, but in action looks mostly ridiculous and out of place with Godzilla and Mechagodzilla. A large amount of the plot revolves around predictions of King Seesar’s return to protect the world from Mechagodzilla, making a sloppy mix of mysticism and science fiction.

King Seesar ends up helpless against Mechagodzilla’s onslaught, but Godzilla shows up in time for an exciting action finale that includes the King of the Monsters discovering powers of magnetism — handy against an enemy made of space titanium. It’s popcorn fun and won’t make you facepalm every few minutes.

Godzilla vs. Mechagodzilla was enough of a success that Toho turned around with a direct sequel: Terror of Mechagodzilla (1975). The studio also brought back director Ishiro Honda for his first feature film in five years. (Like many other directors during the down years, Honda turned to doing television.) Honda infused the story with a seriousness unseen in the series since the early ‘60s, and Terror of Mechagodzilla is unquestionably the best Godzilla movie of the 1970s.

Like the original Godzilla in 1954, Terror of Mechagodzilla is centered on a tragic scientist played by Akihiko Hirata. Hirata this time takes the roles of Dr. Mafune, a biologist whose daughter Katsura almost died in a laboratory accident. However, aliens — the same E.T.s from the previous Mechagodzilla movie — saved Katsura’s life by turning her into a cyborg, and used her to gain control over Mafune for their own plans. They also implanted a device in Katsura that controls the rebuilt Mechagodzilla as well as an underwater dinosaur, the awkward Titanosaurus. Katsura and an Interpol agent investigating Dr. Mafune start to fall in love; Mafune rails against humanity for rejecting his genius; and the aliens have a vague plan to clear Metropolitan Tokyo so they can relocate from their dying world. (At least it’s a plan.) Godzilla shows up, lots of smashing ensues, and everyone ends up happy … except for the majority of the characters who are destined for tragic conclusions.

Terror of Mechagodzilla is a surprisingly downbeat movie for the period. This is certainly Honda’s touch. The human drama, even when the plotting doesn’t make much sense, has gravity that recalls the earlier movies Honda directed. The film still has lightweight monster antics surrounding the grim tale of Katsura and her misanthropic father, and if Honda can’t make the two separate pieces gel together perfectly, it’s completely forgivable. Terror of Mechagodzilla is a film that gets better with each viewing.

Terror of Mechagodzilla is a surprisingly downbeat movie for the period. This is certainly Honda’s touch. The human drama, even when the plotting doesn’t make much sense, has gravity that recalls the earlier movies Honda directed. The film still has lightweight monster antics surrounding the grim tale of Katsura and her misanthropic father, and if Honda can’t make the two separate pieces gel together perfectly, it’s completely forgivable. Terror of Mechagodzilla is a film that gets better with each viewing.

The Hiatus

Terror of Mechagodzilla was not intended as the last Godzilla film for nearly a decade. But it had the poorest box office returns in the series, and with the Japanese economy still in a tailspin from the 1973 oil crisis, Godzilla went on indefinite hiatus. Producer Tomoyuki Tanaka intended to bring the monster back, but he wanted Godzilla to make a splashy, big-budget return… and it took longer than Tanaka expected. Godzilla entered into good old-fashioned Development Hell.

In 1983, Tanaka found what seemed like the perfect solution to bring Godzilla back: have an American studio take over the responsibility of making a blockbuster-sized Godzilla movie. Hollywood director Steve Miner, at that time best known for the second and third Friday the 13th movies, and later to direct House, Soul Man, and Forever Young, made a deal with Toho to develop a Godzilla project to sell to a Hollywood studio.

Miner joined with screenwriter Fred Dekker and artist William Stout to create a package for a movie with the working title of Godzilla: King of the Monsters in 3-D. (This was during a brief 3D resurgence.) Miner shopped around Dekker’s script and Stout’s designs and storyboards during 1983 and 1984, asking for $30 million in funding. The story had Godzilla in a James Bond-style Cold War plot that often sidelined the monster for the espionage story.

Miner came close to securing funding, almost setting it up with Warner Bros. But the asking budget was too high for the studios, who at the time could not see Godzilla as anything other than cheap junk. (I blame Godzilla vs. Megalon.) Miner kept at it, but the process took too long, and Tomoyuki Tanaka got jumpy. The Toho producer finally decided to go ahead with a domestic Godzilla film, not intended for international release so as to avoid tainting potential U.S. interest in funding Miner’s project. However, when New World Pictures bought the U.S. release rights for the new Toho Godzilla film, it killed off the last chance for Godzilla: King of the Monsters in 3-D. It now rests permanently in the “archive” file.

Next: The Heisei Era (1984–1997)

Ryan Harvey is one of the original bloggers for Black Gate, starting in 2008. He received the Writers of the Future Award for his short story “An Acolyte of Black Spires,” and his stories “The Sorrowless Thief” and “Stand at Dubun-Geb” are available in Black Gate online fiction. A further Ahn-Tarqa adventure, “Farewell to Tyrn”, is currently available as an e-book. Ryan lives in Costa Mesa, California where he works as a professional writer for a marketing company. Occasionally, people ask him to talk about Edgar Rice Burroughs or Godzilla in interviews.

I still have a certain amount of misplaced nostalgia for Godzilla vs. Megalon just because it was the first time I ever saw Big G. (On an ABC Sunday night movie or some such.) To this day I’m traumatized by memory of the small Japanese boy in the hot pants.

Godzilla vs. Gigan was my first Godzilla film, under its old Godzilla on Monster Island title. I thought it was the greatest thing I had ever seen. But I don’t have any nostalgic fondness for it, mostly because all the moments I loved the most I later found were lifted from other movies. So those movies now have the nostalgic fondness.

The little kids in tight shorts is a running gag in Japanese films from this periods. Mystery Science Theater 3000 ran with that ball when they watched Invasion of the Neptune Men (Space Pirate Ship in Japan).

I saw Godzilla vs. Megalon in the movies, drawn like several of my friends by the poster putting the duo atop the World Trade Center. That that didn’t happen was the least disappointing thing about the movie.

I had the incredible good (?) fortune of picking up all 3 seasons of Ultraman for like $7. I only managed to watch half a dozen episodes before the cheese got too deep and I had to give it up. But that wacky theme song stuck with me for days.

Alas, another fond remembrance from my youth has fallen by the wayside. I can still remember playing Ultraman in the school courtyard each morning before class began.

The last DVD came with a neat special feature though, a slideshow of all the monsters that the big U encountered, which was a hoot, and saved me from watching all the eps

I’d already spotted him on one of the episodes I watched, but one of the monsters was clearly a sadly repurposed Godzilla suit (needing repair) with a large frill glued onto his neck. U-man of course ripped this off and beat him with it …

Destroy All Monsters (I can still see the pearl) was probably my favorite movies as kid. I’m scared to buy and re-watch it.

Part of my misplaced nostalgia for Megalon is probably due to the fact that I haven’t actually seen it for many years — it was a straggler that didn’t come to DVD until very recently (well, except for the MST3K version?).

Gruud, many of the Ultraman monsters were re-purposed suits from Toho SF flicks, as well as from Ultra Q, the show that proceeded it (which is more adult in tone, and has an X-Files feel to it that makes it far ahead of its time). The monster suit that got re-used the most for Ultraman was the Baragon suit from Frankenstein vs. Baragon. I think it shows up it various guises five times during the original episode run. This was the reason that Baragon got so little time in Destroy All Monsters; the suit was in awful shape.

I unabashedly still love Ultraman and can watch the episodes again and again. There’s just such a wild wonderful innocence to it, and even with the basic plot formula, the show kept changing tones and style, going from outright comedy to sinister secret alien invasion plots to pure psychedelia.

I will be reviewing the entire run of Ultra Q after this Godzilla series is over. It’s a show more people need to know about… and it’s now available for the first time ever in North America. One of the Godzilla suits shows up in the first episode of that show, although it is much more extensively re-designed than the one that appeared in Ultraman in “The Mysterious Dinosaur Base.” The monster goes by the name “Gomess” in Ultra Q. In Ultraman, the monster is called “Jira,” which is a joke, because it’s just “Gojira” with the “Go” cut off. The U.S. dub calls the monster “Kira.”

I think vs. Megalon was also the movie that NBC aired in prime time with John Belushi hosting in a Godzilla suit. It’s generally regarded as Godzilla’s nadir as far as how the American market perceives the franchise.

Yes, Godzilla vs. Megalon did air on NBC with Belushi in a Godzilla suit—making it the only Godzilla film to play prime time on a network. The film was also cut down to 60 mins.

After that, the U.S. rights fell into public domain for a stretch, which meant Godzilla vs. Megalon was available on video everywhere in terrible cropped, blurry transfers, making it ONE OF THE MOST WIDELY SEEN MOVIES IN THE SERIES. And thus, a reason I have to defend the Godzilla to people unfamiliar with it.

Oh, I’ll probably circle back to it. We had watched six in a row, and my son was giving me that sideways “dad has lost his mind” look.

Funny thing is,that yellow and blue swirly psychedelic opening logo gave me an amazing squee moment. I’d forgotten all about it, until I saw it again.

And I love the various aircraft they use, and I’ve always been a big fan of the incredibly detailed modeling done for these sorts of films. I used to dream of doing it for a living.

It aired on the independent station where I grew up, and I think they only bought one season’s worth, two at the most. There were definitely monsters in that slideshow that I don’t recall seeing.

You’ve given me that itch again. Maybe I can just mute during the theme song. 🙂

[…] Part 1: Origins (1954–1962) Part 2: The Golden Age (1963–1968) Part 3: Down and Out in Osaka (1969–1983) […]

[…] A History of Godzilla on Film, Part 3: Down and Out in Osaka […]

[…] 1: Origins (1954–1962) Part 2: The Golden Age (1963–1968) Part 3: Down and Out in Osaka (1969–1983) Part 4: The Heisei Era […]

[…] A History of Godzilla on Film, Part 3: Down and Out in Osaka (1969–1983) […]