Art of the Genre: Artistic Melancholia for the Ruins of the Cyber World

Not to go all ‘Goth Chick’ on you, but have you ever walked in a graveyard? If your answer is no, I’d put money says that you have but you just didn’t realize it. You see, the internet is really a reflection of our own world, with vibrant and glowing real-estate all along the information super highway. Now if you consider each dedicated website as a ‘town’ along this course, what happens when the site goes dormant? I would like to hypothesize that it, and all the ‘people’ [information] in it dies as well. Sure, you can still visit, and perhaps even find out some cool history there, but in truth you are simply walking over the graves of the dead.

Take a site like Grognardia for example, RIP December 11th 2012, or Permission Magazine RIP February 2011, or Stephen Fabian.com RIP June 6th 2010. They still exist, can still be read, but have ceased functioning for all intents and purpose and are now just ghosts in the machine.

Now you might be asking, ‘so what does this morbid topic have to do with Art of the Genre?’ Well, perhaps nothing, but then again, perhaps everything. Each website, no matter how basic, had to have a design, and that design, like a testament to some ancient civilization, is left behind in a kind of ruin that can be viewed by anyone who stumbles off the beaten path into a lost world, but I think I digress, so first let me go back. Seeing these always seems to bring me back to my post here on November 15th, 2012. In it I spoke about the Art of Disappearing MMORPGs, and for some reason I feel the need to speak on the subject a bit more and I apologize if I reiterate some of the topics of that post but I’m in stream of consciousness right now so humor me.

On June 27th 2003, the day after launch, I started playing my first MMORPG, the now deceased Star Wars Galaxies which had the last light turned off on December 15th 2011. Still, for a few choice years this game housed more than a million real life souls on a half-dozen planets in a galaxy far, far away.

I walked digital paths untold during a two year run in this game, and another six month venture years later, but no matter what I remember of the fun of this game, it was the death that really has stuck with me all these years. Now, when I say death, you might be thinking the cyber-blood splatter of my avatar being cut down by a Sith or something, but I’m really going much deeper here.

The death I’m really getting at is that of a game, and not only a game, but the hundreds of thousands of hours of real human energy that went into making it something more than ones and zeroes. You see, Star Wars Galaxies, at least in its initial release, was a builder game. In that, it quickly became something more for many of its players because you were helping create a universe, colonizing planets, and actually making more than you destroyed [which also turned a lot of people off on the game because they wanted a release, not a second job!].

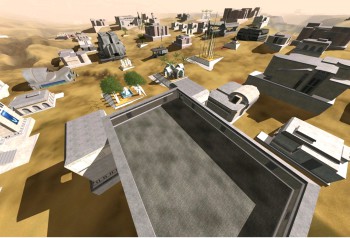

To me, however, this gave the game an incredible digital footprint, but as with all things, this too would come to an end. When I first started the game I had trouble walking from place to place in a starport because there were so many people rushing to and fro on their own lofty business [i.e. lag-city], but by the end I could travel worlds for days in real time without seeing another ‘living’ soul. There was this heads up map you had, and in it you could see an overhead blueprint view around your avatar. At some point I’d walk around with it up, like an old hermit walking among the abandoned streets of various cities doing whatever business I had, and suddenly another colored blip would appear. In my mind I’d wonder, ‘Now who else would be here in this dead place, perhaps I’ll go have a look.’ Something inherently sole survivor and post-apocalyptic took me as I slunk around the city trying to find out who this mysterious stranger was. Indeed, both creepy and exhilarating considering the oppressive silence I endured on most days within the game.

It was in these lonely times, during the melancholia of the game’s twilight years, however, that I began to take stock of the real beauty that a game such as this has to offer.

First and foremost, I thought of all the countless hours artists and programmers had to invest in the base creation, and let me tell you it was stupendous for its day. Incredible sunsets, rainy days, fields of grass blown by unseen winds, waterfalls with rainbows in the mist, ocean waves lapping at a sandy shoreline, and nights with a silvery moonrise sailing into a countless sea of stars.

This, if you’d like my humble opinion, is art, and as my seven year old son loves to ask when he sees a computer game, ‘how did they make that?’. Well, to be honest, I have no idea, but the important part is that they did, and at least someone took notice. I could drift for days through these incredible worlds and landscapes, my speeder bike taking me through hostile terrain and keeping me safe from the lurking dangers of indigenous predatory species. It was an amazing ride, and yet it was always what the game designers didn’t build, the creation of the players, that brought a profound sadness to me.

It was the understanding that the longer I played, the more the game itself would turn into a graveyard, just as those abandoned websites and their creator’s dreams haunt me.

People playing the game had the ability to build homes, you see, almost anywhere there was suitable flat land for the home’s standardized blueprint. In this fashion, friends and guildmates might group their homes together and create a far-flung town in the wilds of Dantooine or Rori. Eventually, these towns would grow to a size where they would get their own blueprint, streets, civic buildings, and governance and during my day I saw many rise up from nothing, but eventually I saw them also dwindle to ghost towns amid the arid plains and damp forests.

It is an eerie feeling if you are sensitive to that kind of thing, walking the streets of an abandoned place where real people, with real hopes and passions, decided to cast their lot and become part of a community. Often, many of the buildings in these cities would be open and you could walk into homes decorated with all the incredible booty of the game, a showcase of the hero’s adventures throughout this universe.

Some of these private homes were incredibly designed museums and true marvels of three-dimensional perspective. Again, countless personal hours of game play had to be incorporated to move each item fractions of an inch to sit perfectly on shelves or create other incredible effects for those the avatar was entertaining.

Again, this is art, and with the help of functional programing, gamers with absolutely no talent with pen or brush created works that could easily have been placed in a book of artistic design for all to see and marvel at.

However, as disturbing as abandoned cities were, I have to say it was the lone homes that troubled me the most. These, like solitary monuments to a better time, could be found in some of the most remote and marvelous places. As a loner myself, I could appreciate the player’s desire to go somewhere that people are not, and each time I saw one I would be compelled to stop. How many times I debarked from my speeder and walked to a lone structure’s door is beyond me, but I remember so many, so well. Often, the doors were locked, but on occasion I could go inside and see the world as this player had seen it, sit in their living room and get some understanding of how they viewed the game, sometimes a prize hunter, sometimes a quest achiever, sometimes a weapon collector, rebel or imperial, and all other manner of things.

There was both a critical and soulful aspect to each inspection. I could perhaps find the person to have been married, which was allowed in the game, or other times a solitary wanderer. The most fun in the inspection was always finding the house’s balcony and standing on it seeing the vista that had inspired the player to build here in the first place.

I built a house once, on Naboo near Theed, just west of the city on a rise above the Vindogo Cliffs. The balcony overlooked the great plain beyond and was the first in that area that later would become a sprawling suburb of Theed itself, but I well remember looking off that balcony the first time and having my breath taken away. Here, indigenous Peku Peku always caught the air currents off the cliffs, and the sunsets were golden and epic along the far horizon of the world drop.

Many of the homes were like this, if more remote, and every time I came to one I tried to take a moment to pay tribute to the real person who constructed it, no matter where they had moved on to or what they were doing in their lives. Perhaps it was a silly thing, but maybe, just maybe, someone will read this and wonder if I found their house and that I appreciated the art they had helped add to this once rich and vibrant world. I would also visit the homes of friends and sit for a time in their abandoned abodes knowing that I’d never see them again no matter how close we had once been in the game. These, oft times, were the most difficult because I knew that one day the money loaded into their house for maintenance would run out and then it would disappear, just like they had the last day they had logged out.

In conclusion, and wrapping this back about to my original question of ‘what does this have to do with Art of the Genre’, well, it has to do with the perception of what art truly is, and at the very core it has always been perceived in the eye of the beholder. Video game art, even if found only on a hard drive, can also be as profound and moving as anything else in the fantasy and science fiction gaming and literature world, perhaps more so because it is art you can actually interact with. This interaction has always brought depth to me, and so I continue to think of it fondly and wish on occasion to see it one last time. Sadly, for games like Star Wars Galaxies, that art is forever gone [unless as Sarah Avery attests that future grad students will fire up old servers to study early 21st century behavior], but some images remain on wayward internet sites, like potshards of a lost civilization, and I think we should cherish them because they are as real and meaningful as anything else created by the will and imagination of the human condition.

If you like what you read in Art of the Genre, you can listen to me talk about publishing and my current venture with great artists of the fantasy field or even come say hello on Facebook here. And my current RPG Art Blog can be found here.

I know the feeling. Though never an overly popular MMORPG, “Rubies of Eventide” still haunts me to this day. It’s small number of users was one of the things that give it a certain charm, and some of that post-apocalyptic element.

Ty: I’ve never even heard of Rubies of Eventide, but I absolutely love the sound of it, kind of strikes a cord in me like the Lamentations of the Flame Princess RPG. Whatever the case, I like to know that there are others that feel the same and are ‘haunted’ by their experiences as I am, because indeed I do believe haunted is the perfect term for it.

I remember well your game ghost towns post. Though I’ve never played a MMORPG, it’s stuck with me. Someone should write a disturbing short story set in one.

Anyhow, it’s lovely to see a post from you. It’s been a while.

Thanks Sarah, I’ve missed you too! 🙂