A History of Godzilla on Film, Part 2: The Golden Age (1963–1968)

Welcome back… the double holiday interruption delayed this march across (and on top of) the Tokyo skyline. But now the Big-G is back and about to enter the Golden Age of Japanese Fantasy Cinema and the peak of kaiju movie greatness.

Welcome back… the double holiday interruption delayed this march across (and on top of) the Tokyo skyline. But now the Big-G is back and about to enter the Golden Age of Japanese Fantasy Cinema and the peak of kaiju movie greatness.

Other Installments

Part 1: Origins (1954–1962)

Part 3: Down and Out in Osaka (1969–1983)

Part 4: The Heisei Era (1984–1997)

Part 5: The Travesty and the Millennium Era (1996–2004)

Addendum: The 2014 Godzilla

The Godzilla Masterpiece: Mothra vs. Godzilla (1964)

The astronomical success of King Kong vs. Godzilla made Toho Studios commit to yearly Godzilla movies for the rest of the decade, as well as increasing their giant monster output in general. The studio shifted away from broader science-fiction epics like The Mysterians: the same year that King Kong vs. Godzilla ignited the box-office, Toho’s more ambitious and expensive science-fiction movie from the team of director Ishiro Honda and special effects creator Eiji Tsubaraya, Gorath, made a poorer showing. From now on, Toho would push that they had monsters and were ready to hurl them against each other for audience’s viewing pleasure.

After briefly considering a King Kong re-match, G-series producer Tomoyuki Tanaka turned to a hometown hero: Mothra, the monster-goddess from the popular 1961 Ishiro Honda film of the same name. Mothra was the point where the Japanese kaiju film came into its own as a specific cultural style different from the US model that first inspired it. The lovely yet powerful Mothra was a perfect foe to put in the opposite corner from Godzilla — at least in terms of box-office appeal. From a story and special-effects perspective, it was a trickier idea: Godzilla fighting a giant mystical moth?

But the creative team came through in an astonishing way: Mothra vs. Godzilla is the height of the Godzilla series and one of the finest monster epics ever put on film. This is the movie to show people at the start of a Godzilla odyssey, since it captures so well the Japanese interpretation of the giant monster genre, has Godzilla at his most charismatic yet menacing, and is more fun than most amusement parks. Eiji Tsubaraya was at his zenith with visual effects; after some wonky optical work in King Kong vs. Godzilla, the effects here are seamless, especially the scenes featuring the miniature Twin Fairies (the shobijin, played by pop singing duo The Peanuts). The two monster battles, with Godzilla against the adult Mothra and then against two larval Mothras, are thrillingly staged and scored.

Mothra vs. Godzilla lacks the heavy, bleak artistry of the original Godzilla, but as movie entertainment it excels. Breathlessly paced, with fantastic villains and energetic heroes, the story follows an exciting trajectory of Japan seeking help from Mothra to defeat Godzilla’s destructive return — only to receive a harsh “no” from the inhabitants of Mothra’s island. But Mothra changes its (her?) mind at the last minute when Godzilla threatens Mothra’s egg, leading to a standstill battle that Mothra only loses because it comes to the end of its life-cycle. But, in a wonderful example of turnabout and the underdog winning the day, Mothra’s egg hatches, and two larval Mothras dish out a clever and humiliating defeat to the King of Monsters. It’s awesome.

And Godzilla is awesome, in the truest sense of the word: an awe-inspiring beast who has shifted from the more comical personality of the previous film to Mr. Get the Hell Outta My Way. Godzilla’s first rampage through the city of Nagoya has the monster realistically reacting to the devastation it causes, which includes a stunning scene of the monster accidentally knocking into a Shogun castle, and then beating it into rubble just to show that stupid building who’s boss. Godzilla blooms into a fully realized character, and what an amazing show the Big-G puts on. Godzilla is still the villain, but every minute the monster is on screen is a blast.

And Godzilla is awesome, in the truest sense of the word: an awe-inspiring beast who has shifted from the more comical personality of the previous film to Mr. Get the Hell Outta My Way. Godzilla’s first rampage through the city of Nagoya has the monster realistically reacting to the devastation it causes, which includes a stunning scene of the monster accidentally knocking into a Shogun castle, and then beating it into rubble just to show that stupid building who’s boss. Godzilla blooms into a fully realized character, and what an amazing show the Big-G puts on. Godzilla is still the villain, but every minute the monster is on screen is a blast.

It was only a short leap to somebody at Toho thinking, “Hey, what if Godzilla saved the day?”

Mothra vs. Godzilla reached the U.S. in record time, debuting in theaters only five months after its April opening in Japan. American International Pictures handled the release with the best-dubbed of all Godzilla movies. Not only was the Japanese original left virtually uncut, but AIP included an extra visual effects scene of U.S. warships firing on Godzilla which Toho shot specifically for the American release. The only odd part about AIP’s version of the film is the decision to retitle it Godzilla vs. The Thing, an attempt to disguise Godzilla’s foe for publicity reasons. Later U.S. video releases titled the film (on the cover art, at least) Godzilla vs. Mothra, giving Godzilla first place on the fight ticket for alphabetical shelving purposes.

Aliens and the Golden Dragon: Ghidorah, The Three-Headed Monster (1964) and Invasion of Astro-Monster (1965)

“More monsters, more monsters!” Toho cried, and the next Godzilla film, Ghidorah, The Three-Headed Monster, came out eight months later, featuring four kaijus. (A more detailed discussion of it if you have time.) The movie brought back Mothra, re-introduced flying beast Rodan (last seen in its own self-titled film in 1956), and created the most magnificent of all Godzilla adversaries, the tri-cephalic golden space dragon King Ghidorah.

King Ghidorah (shortened to “Ghidrah” in the U.S. release) shows how much Toho and special effects director Eiji Tsubaraya were willing to ramp up the fantasy elements of these movies: even in a setting with a goddess-moth and two radioactive dinosaurs, a three-headed golden dragon who ravishes planets over thousands of years is pretty damn out there. King Ghidorah made a huge hit with audiences and has remained a major force in Toho’s monster line-up.

Extra-terrestrials were familiar adversaries in Japanese films of the last decade, and the team of Eiji Tsubaraya and Ishiro Honda had already made two epic alien invasion films, The Mysterians and Battle in Outer Space. Ghidorah, The Three-Headed Monster was the first time alien elements entered the Godzilla series, although it isn’t a full-fledged invasion film; that would wait for the next movie in the series. It features an alien-possessed character (Akiko Wakabayashi, later to play a Bond girl in You Only Live Twice) and a monster from space wreaking havoc on Japanese cities in scenes of astonishing lightning-laced demolition. Away from the monsters, the plot is crime movie material, with a team of assassins in sunglasses tooling around Tokyo trying to assassinate a princess.

The movie marks an even bigger milestone in Godzilla’s history: for the first time, Godzilla plays the good guy — a reluctant hero, but still someone audiences root for. Godzilla remains an engine of destruction and spends most of the movie in a petty grudge match with Rodan that wrecks large amounts of public property. But at the climax Godzilla and Rodan agree with Mothra that it is in everyone’s best interests if they beat the daylights out of that cackling three-headed space jerk. Which they do, in one of the most satisfying monster fights ever filmed. The switch is abrupt, but when Godzilla hurls that first rock at King Ghidorah’s head, it’s impossible not to cheer.

The movie marks an even bigger milestone in Godzilla’s history: for the first time, Godzilla plays the good guy — a reluctant hero, but still someone audiences root for. Godzilla remains an engine of destruction and spends most of the movie in a petty grudge match with Rodan that wrecks large amounts of public property. But at the climax Godzilla and Rodan agree with Mothra that it is in everyone’s best interests if they beat the daylights out of that cackling three-headed space jerk. Which they do, in one of the most satisfying monster fights ever filmed. The switch is abrupt, but when Godzilla hurls that first rock at King Ghidorah’s head, it’s impossible not to cheer.

King Ghidorah returned for the next movie, Invasion of Astro-Monster, which U.S. audiences know better under its first American release title Monster Zero, or video box title Godzilla vs. Monster Zero. Invasion of Astro-Monster unites two separate strands of Toho’s science-fiction film canon: the kaiju film and the alien invasion film. Earth now faces a full attack from outer space, with its own monsters turned against it. This was a theme that would re-occur throughout the remainder of the classic era.

Aliens from Planet X deceive the nations of Earth into sending Godzilla and Rodan to their planet, supposedly to help them defeat King Ghidorah. But King Ghidorah was already under the control of Planet X, and the scheming aliens send a brainwashed Godzilla and Rodan, along with Ghidorah, to smash Earth into submission! The people of Planet X fail thanks to their trouble with high-pitched sounds, and the freed Rodan and Godzilla pummel King Ghidorah again.

Invasion of Astro-Monster is the most visually epic of the classic Godzilla series. Destroy All Monsters may pack in more big beasts for an all-star cast, but Astro-Monster looks and feels grander, with Toho Visual Effects Department executing astonishing planetary vistas and gargantuan military assaults. The alien plot pushes the monsters a bit to the sidelines, which is why Astro-Monster feels a touch inferior to the two previous movies; but as a straightforward science-fiction film, it’s a good ride.

Invasion of Astro-Monster was co-financed with United Productions of America, the studio responsible for the Mr. Magoo cartoons and the move toward stylized animation in the 1950s, and its owner, Henry G. Saperstein. UPA put up half the budget for the film, and allowed Toho to land a fading American star, Nick Adams, as one of the leads. Adams appeared in three Toho films and is a beloved icon for kaiju fans because of how he threw his full tough-guy persona into the parts, which makes a fun contrast with the Japanese actors. Hearing Adams snarl, “Why you rats!” to the Planet X aliens is wonderful. You can only get the full effect of Nick Adams’s performance in the English-dubbed version, where Adams’s own voice (recorded on the set) is used. However, watching the dubbed version means you miss out on the film’s other stellar performance, Yokio Tsuchiya as the Controller of Planet X, which is the definition of “quirky.” Somebody needs to create a combined version with Adams speaking English and everybody else subtitled.

Invasion of Astro-Monster was co-financed with United Productions of America, the studio responsible for the Mr. Magoo cartoons and the move toward stylized animation in the 1950s, and its owner, Henry G. Saperstein. UPA put up half the budget for the film, and allowed Toho to land a fading American star, Nick Adams, as one of the leads. Adams appeared in three Toho films and is a beloved icon for kaiju fans because of how he threw his full tough-guy persona into the parts, which makes a fun contrast with the Japanese actors. Hearing Adams snarl, “Why you rats!” to the Planet X aliens is wonderful. You can only get the full effect of Nick Adams’s performance in the English-dubbed version, where Adams’s own voice (recorded on the set) is used. However, watching the dubbed version means you miss out on the film’s other stellar performance, Yokio Tsuchiya as the Controller of Planet X, which is the definition of “quirky.” Somebody needs to create a combined version with Adams speaking English and everybody else subtitled.

For reasons that Henry G. Saperstein never adequately explained, Invasion of Astro-Monster had a long delay reaching stateside screens despite U.S. co-financing. The movie finally came out in 1970 as Monster Zero on a double-bill with War of the Gargantuas — five years after its Japanese release.

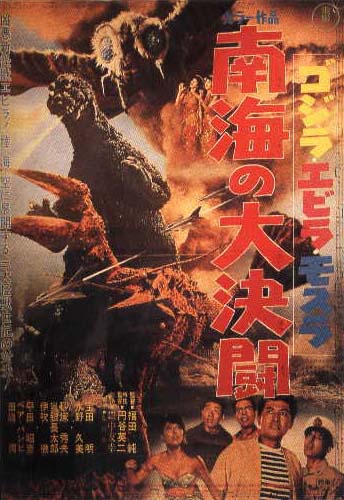

Island Vacation: Ebirah, Horror of the Deep (1966) and Son of Godzilla (1967)

Japan’s mania with monster films reached its apex in 1966–67. Other studios started to try out the genre that Toho had dominated until then. Daiei started its successful “Gamera” series, which aimed directly at an audience of children, and the fantastic “Daimajin Trilogy” set against a feudal Japanese background. Shochiku released The X from Outer Space, a combination of swinging ‘60s SF party and a giant space-chicken-muppet-thingy (it’s as groovy as it sounds). Nikkatsu gave the world Giant Monster Gappa, released to U.S. television as Monster from a Prehistoric Planet.

Toho only got busier, turning out multiple giant monster epics during these years. Ironically, Godzilla ended up pushed to second chair in the string section. The next two G-films were shot on tighter budgets with a different creative team, and they mark a significant change in style from Ishiro Honda’s SF epics. But the shift turned out surprisingly well, although it has taken most Godzilla fans years to embrace Ebirah, The Horror of the Deep and Son of Godzilla as enjoyable departures from formula.

Toho only got busier, turning out multiple giant monster epics during these years. Ironically, Godzilla ended up pushed to second chair in the string section. The next two G-films were shot on tighter budgets with a different creative team, and they mark a significant change in style from Ishiro Honda’s SF epics. But the shift turned out surprisingly well, although it has taken most Godzilla fans years to embrace Ebirah, The Horror of the Deep and Son of Godzilla as enjoyable departures from formula.

Ebirah, Horror of the Deep (released to the U.S. as Godzilla versus the Sea Monster) started as a script for Toho’s return of their version of King Kong, a project co-produced with U.S. animation company Rankin/Bass. When Rankin/Bass rejected this first script, Toho turned it around and made it into a Godzilla picture, which explains some of Godzilla’s out-of-character behavior, like sleeping in a cave on a tropical island and occasionally displaying interest in a native girl.

The King Kong project was eventually made as King Kong Escapes (1967) with the Honda-Tsubaraya team at the helm. Over at Ebirah, Horror of the Deep, tough-guy action movie director Jun Fukuda was brought on, and Eiji Tsubaraya’s assistant Teisho Arikawa handled the effects.

Ebirah takes place almost entirely on a tropical island with a group of stranded youths and a clever thief running afoul of an Evil Organization (a thinly disguised version of Mainland China) and their giant guardian lobster, Ebirah. But Godzilla is also on the island, and mayhem ensues until Mothra makes a brief appearance to rescue our heroes. The urban destruction of the earlier Godzilla movies is gone, and in its place is an adventure story with heavy James Bond influences. In fact, the movie bears a striking resemblance to Dr. No in setting and plot. Although Ebirah is a lame monster as far as Godzilla’s pantheon of foes goes (a big lobster, nothing more or less), the film is exciting and well-paced, and the cast of familiar actors from the G-series, including Akira Takarada as the charming thief and Akihiko Hirata as an eye-patch-wearing sub-vaillain, are fun to watch.

Not so fun: Ebirah, Horror of the Deep became the first Godzilla movie to skip a U.S. theatrical release. It went straight to syndicated television through the Walter Reade Organization in 1968. Tastes in the U.S. were shifting, and the days of major studios purchasing Toho’s product were over.

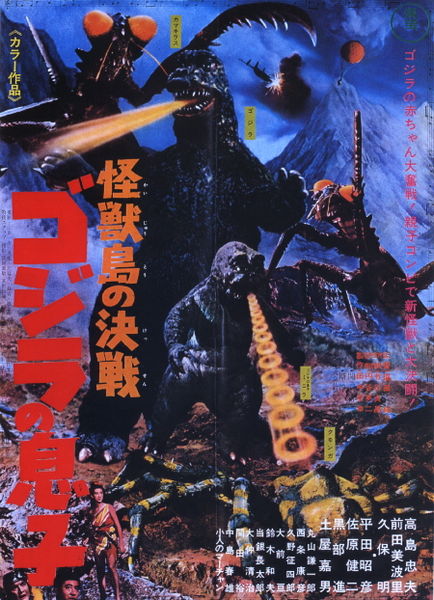

Toho repeated the island experiment the next year with the same crew. Son of Godzilla has the team of a science station stranded on an island filled with giant praying mantises (Kamacuras) and a horrifying super-spider (Kumonga). Life turns both cute and extra dangerous when an egg hatches an infant Godzilla (Minira, often written as “Minya” or “Minilla” in English) and the parental figure comes crashing onto the island to make sure the bugs don’t bother junior.

Minira is adorable, although the roly-poly doughboy creature looks nothing like Godzilla. The scenes between the two monsters are personable and sometimes touching. However, Son of Godzilla remains a serious adventure film most of its running time, focusing on the trapped humans and their survival struggle. At times, the movie turns downright frightening: usually, giant monsters remain oblivious to humans, but Kumonga actively pursues and tries to kill the heroes. The film isn’t afraid to put poor Minira in serious jeopardy as well.

Minira is adorable, although the roly-poly doughboy creature looks nothing like Godzilla. The scenes between the two monsters are personable and sometimes touching. However, Son of Godzilla remains a serious adventure film most of its running time, focusing on the trapped humans and their survival struggle. At times, the movie turns downright frightening: usually, giant monsters remain oblivious to humans, but Kumonga actively pursues and tries to kill the heroes. The film isn’t afraid to put poor Minira in serious jeopardy as well.

Son of Godzilla of course begs the questions: Is Godzilla male or female? Is Minira really Godzilla’s “son,” or just a member of the same species Godzilla adopted? The mystery remains to this day.

The Big Finish (But Not Really): Destroy All Monsters (1968)

Toho recognized that the giant monster genre was about spent after the two-year splurge. The studio planned to finish off the Godzilla series with a mad monster party, Toho’s own version of House of Frankenstein, and crammed eleven monsters together along with more alien invaders and a toy-ready super-spaceship. Although not the greatest Godzilla film ever made, Destroy All Monsters is perhaps the quintessential monster-rally flick, and the closest the series came to a pure 1960s comic book style. Godzilla: Final Wars in 2004 would throw even more monsters into the mix, but Destroy All Monsters is the movie people remember, and is forever identified with the idea of fan-pleasing crossover events.

I’ve already written extensively about Destroy All Monsters at Black Gate for the movie’s Blu-ray release, so I’ll keep it brief here. The enormous cast of monsters necessitated a simplified plot that could quickly incorporate all of them. Toho returned to the concept of aliens mind-controlling Earth’s monsters to turn them against humanity. Earth’s heroes eventually undo the alien control, and the monsters have a showdown with the aliens’ last-ditch ploy, King Ghidorah. If this sounds familiar, that’s because it’s the same story as Invasion of Astro-Monster, but with much of the human drama removed to accommodate the large number of kaijus. This is where Destroy All Mosnters lags behind some of the earlier films: the story and its protagonists are so meager that there isn’t much away from the monsters that’s interesting to watch. Comparing it to Invasion of Astro-Monster shows its dramatic deficiencies. But there is no denying that the two major special-effects set pieces — Godzilla, Rodan, Mothra and Manda wrecking Tokyo under a massive missile barrage; the full monster gang taking on King Ghidorah at the foot of Mt. Fuji — are tremendous spectacles.

Destroy All Monsters was the last Godzilla movie to have all four Godzilla Fathers — Honda, Tsubaraya, Tanaka, and Ifukube — working together. (Tsubaraya died in early 1970). It was the close of an era. Although Toho reneged on their plan to end the Godzilla series almost immediately, for the rest of the Showa era, life was going to get considerably more… economical.

NEXT: Down and Out in Osaka (1969–1983)

Ryan Harvey is one of the original bloggers for Black Gate, starting in 2008. He received the Writers of the Future Award for his short story “An Acolyte of Black Spires,” and his stories “The Sorrowless Thief” and “Stand at Dubun-Geb” are available in Black Gate online fiction. A further Ahn-Tarqa adventure, “Farewell to Tyrn”, is currently available as an e-book. Ryan lives in Costa Mesa, California where he works as a professional writer for a marketing company. Occasionally, people ask him to talk about Edgar Rice Burroughs or Godzilla in interviews.

There is nothing cooler than King Ghidora. With the possible exception of Mecha-King Ghidora, but that will be another column …

I’ve been waiting with bated breath for the continuation of these kaiju chronicles! Looking forward to the next couple installments, which will fill in some major gaps in my Godzilla knowledge.

Mothra vs. Godzilla through Invasion of Astro-Monster is the peak of the series to me, and a major reason why I feel the Showa era Godzilla is the one true Godzilla. I just think they’re ideal “comic book” type movies, with the personalities they give the monsters, the colorful effects, alien invaders, gangsters and spies, etc. I realize that whenever someone reboots the franchise they usually want to harken back to the grim original, but inwardly I’m always hoping someone will bring back the fun of these movies (except, you know, better than Final Wars turned out).

[…] 1: Origins (1954–1962) Part 2: The Golden Age (1963–1968) Part 3: Down and Out in Osaka […]

[…] 1: Origins (1954–1962) Part 2: The Golden Age (1963–1968) Part 3: Down and Out in Osaka (1969–1983) Part 4: The Heisei Era […]