“A Fighting Fantasy Gamebook In Which YOU Are The Hero!”: The Warlock of Firetop Mountain

It’s a time for looking back, as the old year ends. Now so it happens that on a Boxing Day sale I picked up a book I loved as a child; and therefore it seems fitting to write a little about it, now, glancing back down the vanished days of this and other years, and to try to again see the pleasure I once had. Will it come again, as I work through the text? If I work on the text, then no. Because this text, more than most, is not made for working. It is a thing to be played.

It’s a time for looking back, as the old year ends. Now so it happens that on a Boxing Day sale I picked up a book I loved as a child; and therefore it seems fitting to write a little about it, now, glancing back down the vanished days of this and other years, and to try to again see the pleasure I once had. Will it come again, as I work through the text? If I work on the text, then no. Because this text, more than most, is not made for working. It is a thing to be played.

This is not a story I once loved, except in a way it is. There’s no strong central protagonist, except that in a way there is that as well. It’s a book-length riddle. It’s a maze through which you must find your way, filled with wrong turnings and frustrating locks. It is a story you can shape with a pencil and two dice: you are a hero with a sword, who must explore a wizard’s underground lair, before finally defeating the great mage in battle and taking his treasure. You choose your own adventure, flipping from one numbered section to another depending on the decisions you take faced with a given situation. More than most novels, the reader must shape the story; for the reader is the hero. This is The Warlock of Firetop Mountain, written by Steve Jackson and Ian Livingstone. First published in 1982, it was the first of what became a line of several dozen gamebooks, as well as a full-fledged role-playing game. Warlock inspired direct sequels, a computer game, and even several non-interactive novels. You can learn more about the books at their web site.

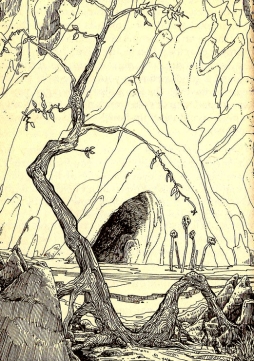

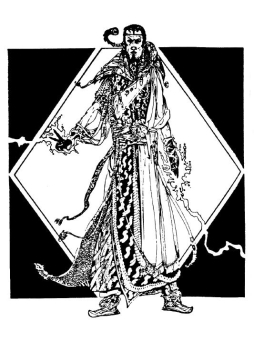

Not long ago, Black Gate’s redoubtable Nick Ozment looked at The Warlock of Firetop Mountain and several other of the Fighting Fantasy gamebooks. Nick remembered playing other Fighting Fantasy books, but not this one specifically. My experience roughly mirrored his: it was relatively easy to get to the end of the book, but incredibly difficult to actually win a complete victory. Nick liked the art — Firetop’s profusely illustrated by Russ Nicholson (you can see some of these pictures below) — but found the conception of the book’s dungeon improbable. I agree with both points. But I found myself wondering if there wasn’t something else to say about the book. I remembered playing through it in the early 80s, drawing out maps, trying again and again to make it through to the end. Why was I held so deeply in the book’s spell? Does it hold up?

Looking at the book anew, I find the answer to the last question is both yes and no. There are good things and bad in it. I think the power it had for me as a child can only be explained by how all the different elements come together.

Looking at the book anew, I find the answer to the last question is both yes and no. There are good things and bad in it. I think the power it had for me as a child can only be explained by how all the different elements come together.

To start with: the rules are excellent. They’re complex enough to be memorable, but simple enough to play quickly. You generate a character with three statistics — skill, stamina, and luck. With those stats you can battle monsters, or roll a check to see whether you succeed or fail at a given task. The stats will help determine the choices you make and, to some extent, what happens to you. Your skill or luck may help decide which path through the mountain you end up taking. And comparing your skill and stamina with those of a potential combat opponent will help you decide if you really want to see the fight through or beat a hasty retreat. Generally the book’s very inventive in finding ways to use the three stats.

Similarly, the book’s basic mechanic of flipping from section to section is well handled. There’s an extended maze section that functions as a series of loops, sending you around and around as you look for exits. And there’s a ‘wandering monster’ section to which you’re directed at certain points, if you’re unlucky enough to meet a random dungeon denizen. These bits of the book get reused in an almost modular way, a clever mechanic that gets the most out of the text. Finally, to really ‘win’ the book you need to gather numbered keys; adding the numbers of the right keys together gives you the number of the section that confirms your victory.

The individual encounters are highly varied. There’s combat, negotiation, traps, and random magic. You can’t use the same tactic all the time, and you have to assess whether a given interaction calls for violence or discussion. Some encounters can simply be bypassed — but some are crucial to success.

The individual encounters are highly varied. There’s combat, negotiation, traps, and random magic. You can’t use the same tactic all the time, and you have to assess whether a given interaction calls for violence or discussion. Some encounters can simply be bypassed — but some are crucial to success.

And this is one of the two flaws in the mechanics of the book. The crucial encounters aren’t flagged in any way. You have no idea which fights you have to go through in order to get the keys to win a true victory. More, there are several paths through the mountain, and in some cases choosing a ‘left’ when you should have taken a ‘right’ will make victory impossible. Again, the correctt path isn’t at all marked.

Secondly, even on the right path, and even if you fight the right battles, you’ll need some luck. The book’s introduction promises that “any player, no matter how weak on initial dice rolls, should be able to get through fairly easily.” I’m skeptical of that claim. Two of the needed keys are kept by fairly strong monsters. Without fighting them you can reach the end, but not win.

I wonder whether these flaws aren’t to some extent deliberate. The book’s deliberately structured so that you can’t usually go back along your path to paths untaken; you’re always conscious that there were other options. So when you reach the end the first time through, and fail, you know you can do things differently and maybe have a better result. The difficulty’s deliberate, encouraging replays.

I wonder whether these flaws aren’t to some extent deliberate. The book’s deliberately structured so that you can’t usually go back along your path to paths untaken; you’re always conscious that there were other options. So when you reach the end the first time through, and fail, you know you can do things differently and maybe have a better result. The difficulty’s deliberate, encouraging replays.

So the mechanics are challenging. What about the story? The plot’s rudimentary. It’s a basic dungeon-crawl: kick in the doors, kill the monsters, take their stuff. There’s no overall quest driving your character, only greed.

The world of the dungeon is basically incoherent. Nothing keeps you out of the dungeon. Nobody in the dungeon’s surprised to see a visitor. Monsters live beside each other with no particular concern for ecology or plausibility. A ferryman conducts travellers across a river, and a merchant sells blue candles, with no sense of economic plausibility (two or three gold pieces get you across the river, but the candle goes for twenty). Which is really the point.

The macro-scale worldbuilding’s almost irrelevant. It’s the small-scale stuff that sticks in your mind. Drunk orcs. Dwarves playing cards. Skeletons “are pretty dim.” The ferryman tries to cheat you. There’s something weirdly alive in all this. These are individual creatures with individual reactions, who you can approach in different ways.

The macro-scale worldbuilding’s almost irrelevant. It’s the small-scale stuff that sticks in your mind. Drunk orcs. Dwarves playing cards. Skeletons “are pretty dim.” The ferryman tries to cheat you. There’s something weirdly alive in all this. These are individual creatures with individual reactions, who you can approach in different ways.

Stylistically, the book’s language is very clear, good Young Adult-oriented prose. It’s relatively intelligent without being obtrusively clever, I feel, and without being spectacular it feels distinctive. The various challenges are surprising but also pleasingly archetypal: orcs and skeletons, pits and mazes. Somehow they create a sense of a distinctive place, even though the labyrinth under the mountain isn’t really given much sensory description. Perhaps it’s that the things you find have an almost folkloric resonance. Two helmets on a table, one iron and one bronze: will you try one on? A crypt in which a coffin lid slowly opens: will you fight the creature within?

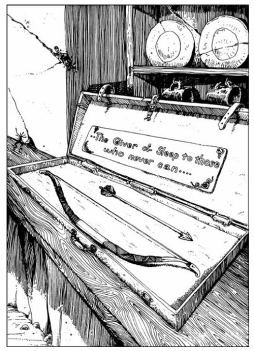

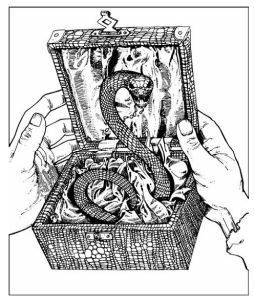

But I think what really makes the dungeon come alive is Nicholson’s art. It’s filled with imaginative details: the stitching on leather armour, the earring an orc wears, the skull at a minotaur’s belt, plates and cups on a shelf above an open case holding a bow and arrow. His linework’s excellent as is his composition — both are baroque without being cluttered. There’s no doubt that his depiction of the dungeon sparked my imagination as a young reader.

More than that, the illustrations have an odd effect as you play through the book. As you flip from place to place, you see the pictures that belong to other sections. You’re curious, tantalised. You wonder where that bow is, and what’s the story behind the man sitting before a shelf of books with a strange winged creature upon his shoulder. You start hoping or dreading that you’ll come across the right bits of story; that you’ll play through the pictures you see.

More than that, the illustrations have an odd effect as you play through the book. As you flip from place to place, you see the pictures that belong to other sections. You’re curious, tantalised. You wonder where that bow is, and what’s the story behind the man sitting before a shelf of books with a strange winged creature upon his shoulder. You start hoping or dreading that you’ll come across the right bits of story; that you’ll play through the pictures you see.

Somehow the art and the distinctive sense of individuality in the book makes it feel like a whole. You really do seem to play through a story, despite the simple plot and implausible worldbuilding. There’s not much of a sense of character beyond the choices you make, so ‘story’ here is best interpreted loosely. It may be more accurate to say that you seem to be playing your way through a dream, filled with strange things and incoherent events, and in which you have a limited field of action. There’s no sense of past to anchor your character, only one thing after another.

Add to that the fact that the nature of the game makes the pattern of tension and release very different from what you find in a story. You ask not ‘what happens next’ but ‘what will this do,’ with the point of maximal tension being the flipping of pages. Reading the section to which you’re directed is a letting-out of drama. The choice has been made. There only remains the result.

Add to that the fact that the nature of the game makes the pattern of tension and release very different from what you find in a story. You ask not ‘what happens next’ but ‘what will this do,’ with the point of maximal tension being the flipping of pages. Reading the section to which you’re directed is a letting-out of drama. The choice has been made. There only remains the result.

You don’t end up with a traditional sense of identification. You get instead a highly distinctive sense of immersion. There’s a theory in comics art I’ve come across which says that readers respond surprisingly well to highly-detailed background art but very simply-drawn lead characters. The idea is that the less distinctive the main character, the more the reader can project him- or herself into the lead; and, conversely, the more the background feels realistic, the more the reader has a sense of being in an actual place. Something like that seems to be going on here.

I found the game still enjoyable, even involving, though this may well just be because of my previous experience. As I remember, later books in the series were better, with more varied rules. I wonder how the video game adaptations of the Fighting Fantasy books have been; if anything, the books are similar to the text-adventure style of computer game so prominent in the early 80s. Modern games are more forgiving than Warlock, I think. Still, all in all, I think the book format may be best: there’s a certain effect the mix of image and text gives you that I can’t imagine in other formats. All told, I’m glad I picked the book up again. There’s magic in Firetop Mountain yet.

I found the game still enjoyable, even involving, though this may well just be because of my previous experience. As I remember, later books in the series were better, with more varied rules. I wonder how the video game adaptations of the Fighting Fantasy books have been; if anything, the books are similar to the text-adventure style of computer game so prominent in the early 80s. Modern games are more forgiving than Warlock, I think. Still, all in all, I think the book format may be best: there’s a certain effect the mix of image and text gives you that I can’t imagine in other formats. All told, I’m glad I picked the book up again. There’s magic in Firetop Mountain yet.

Matthew David Surridge is the author of “The Word of Azrael,” from Black Gate 14. His ongoing web serial is The Fell Gard Codices. You can find him on Facebook, or follow his Twitter account, Fell_Gard.

“The various challenges are surprising but also pleasingly archetypal: orcs and skeletons, pits and mazes. Somehow they create a sense of a distinctive place, even though the labyrinth under the mountain isn’t really given much sensory description. Perhaps it’s that the things you find have an almost folkloric resonance.”

An intriguing observation about the “almost folkloric resonance,” coupled with your description a bit later of “playing your way through a dream.” I hadn’t really thought of it that way before, but I think you may be onto something.

As a kid, my favorite role-playing adventures were the ones that offered the most eclectic variety of surprises: incongruent traps and exotic monsters; the more the merrier! As I got older and more discerning, I naturally questioned the rationale behind the settings and scenarios, demanding that “inner consistency” of world-building that Tolkien expounded on.

But I continued to crave variety, still do. When it comes to D&D, give me a good ol’ dungeon crawl offering up everything from beholders and black puddings to umber hulks and xorns. To me, a classic adventure is one that can offer up that kind of variety while grounding such eclecticism in some logical premise, however implausible.

I’d dismissed the randomness of settings like Firetop Mountain and the TSR board game Dungeon! as just the over-simplicity of something that is more game than story–closer in kinship to Candyland than a Pathfinder campaign. But this notion of the grouping of standard tropes and archetypes gives another lens to look at them — another way to categorize them. There may be no logical world-building sense in a bunch of skeletons “living” in a room next to a family of dwarves across the hall from a tribe of kobolds. But they do all fall into the same category of fantasy myth and folklore. They all share a distinct feel; they’re all “of a piece.”

That doesn’t give you a pass if you try to get away with it as a DM. You’d better have a good explanation for your players as to why the skeletons don’t attack the dwarves and why the kobolds and dwarves share a truce. But it helps to make sense of why one can play through this sort of adventure without getting hung up on such niggling questions.

Matthew, Nick,

Thanks to both of you for paying some attention to these books. I was quite mesmerized by them as a teenager! I probably obsessed over solo RPGs the way my own kids obsess over videogame RPGs.

I have very fond memories of the Metagaming titles, especially DEATH TEST and DEATH TEST II, but these books were a close second.

The FF books were also extremely popular — almost a publishing phenomenon, especially in Britain.

Thanks for the comments, John and Nick!

Nick, I think there`s some kind of distinctive weirdness to early RPGs, at least to D&D or Fighting Fantasy. Like you, I was always drawn to the strangeness that somehow created that distinctive-yet-unified feel. I`m glad these thoughts seem to make sense. Lately I find myself trying to distinguish between different kinds of fantastic weirdness — some fantasy feels like a dream, some like a myth, and so on. I don`t really know where it`ll lead, but it`s interesting to think about.

I actually took out Warlock recently and tried it with my two boys. Fudged a bit as it was never a multiplayer book. Funny thing is I recall gettin this long after I had got other later titles and finding it a bit silly, also too easy as I finished it first time – after a friend had told me how hard it was.

All I can say now is yes it is hard, I must have just been really lucky way back when I tried it. My kids and I sumbled aroundfrustratibgly.

These books I still fondly remember. I’m eagerly buying them again as they are released on Android. Finally beat “Isle of the Lizard King” which I was never able to do earlier and played it with the computer in the tablet keeping score so I knew I did it 100% legit.

Frankly, I’m thinking of making some “Fighting Fantasy” style adventure stuff as part of the stories I’m writing. I like it that much, but IMO it might seem out of place. If I put together a collection of stories, my style more in the spirit of REH, CAS and stuff, and one of them is such a thing… I probably should exclude it and add things like games made with DIY kits so simpler than modern games I don’t have time/$ to make but like older games in the past, but better graphics and don’t have to type every pixel in ….bleep… machine language.

Reposting this as previous comment only seems to show if i am logged in?

GreenGestalt – go for it. Yes the FF books were aimed at younger audience, but there is stil a following for those type books. Look at per example http://www.arborell.com

Also agree its a time thing, guys who don’t have time to sit alone on PC or would love to role play but are sans group, I think there is an audience.

Funny enough back in 80′s I took it upon myself to write a FF story. Very manual, used my mothers typewriter, still recall her complaining that I used up all her ribbon. Found the manuscript the other day, with rejection letter from Mark Gascoine at Puffin Books UK. Maybe I should scan it in and see if I can digitise the texts with in document hyperlinks and post it online. Then again there was a reason it was rejected:)

Tiberius — just FYI. All comments that include a URL are held in queue until they can be approved manually (that’s a precaution to prevent spam postings).

I approved yours as soon as I saw it this morning, and deleted your original post so there wouldn’t be two. 🙂

Thanks John, I was not aware of that.

Have you encountered Arobrell before? I have browsed the site but have not yet played any of their games.

To Tiberius…

Just a quick FYI – I’m running the Demo on Xara’s web designer pro, and will probably buy it. One thing I noticed is that it can make entire huge webpages in the same document. So you can draw shapes, or have text/pictures, linked to other pages in the same working document. Now, maybe I’m baiting a laugh track since I’ve never cared about recent HTML stuff, just manually worked things out in notepad or used ancient editors, but it’d be perfect for a “Choose your path” story, maybe needing some simple programming for a special widjet for stats/health, the cliche RPG stuff?