A History of Godzilla on Film, Part 1: Origins (1954–1962)

Other Installments

Other Installments

Part 2: The Golden Age (1963–1968)

Part 3: Down and Out in Osaka (1969–1983)

Part 4: The Heisei Era (1984–1997)

Part 5: The Travesty and the Millennium Era (1996–2004)

Addendum: The 2014 Godzilla

With the release of the teaser trailer for the upcoming Godzilla from Warner Bros. and Legendary Pictures, a decade of cinematic silence has come to an end. Godzilla last appeared in 2004 in the Japanese movie Godzilla: Final Wars, which Toho Studios intended as the monster’s final bow before going on sabbatical. It’s the longest break in the iconic monster’s career, and regardless of what happens next, the forthcoming Godzilla ’14 is a reason for G-fans to celebrate. Maybe stomp a few cities. The trailer makes San Francisco look particularly stomp-able.

At this point, we only know as much about Godzilla ’14 as we’ve seen in the teaser. But it was an exciting glimpse that at least assured fans the new movie would not repeat the horrible mistakes of the first American attempt at a stateside Godzilla, the 1998 Roland Emmerich disaster.

This is the first of five (projected) installments covering the history of Godzilla on film, written and condensed for a broad audience. I hope these articles will help readers who have only a passing relationship with Godzilla — the general knowledge from pop culture osmosis — see the unusual variety of one of the longest and most durable film franchises in history. Many Black Gate readers are probably familiar with much of the information I’ll provide in these articles, but since I’ll also sling around my own opinions about the movies mixed in with the history, Godzilla fans may find parts of this worthwhile … if perhaps only to ignite arguments.

Terminology and Other Business to Dispense With

Godzilla’s film history divides into three distinct phases: The Showa series, also known as the “classic series” (1954–1975), named after the period of the reign of Emperor Hirohito; the Heisei series (1984–1995), named after the reign of Emperor Akihito; and the Millennium series (1999–2004), named after the inaugural film, Godzilla 2000: Millennium (1999). The first three installments of this history will cover the Showa movies, and the last two will cover Heisei and Millennium, as well as the hiatuses between.

For clarity and consistency, I’ll refer to the movies by the official English titles Toho Studio gave them for the purpose of foreign sales, and use the alternate U.S. titles for specifically Americanized releases. For example, I will refer to the first movie of the Heisei series as The Return of Godzilla (1984) and its Americanized version as Godzilla 1985. I will point out the more familiar U.S. titles when they are drastically different from the official Toho title, such as Godzilla versus the Sea Monster, the U.S. television and video title of Ebirah, Horror of the Deep.

Black and White Beginnings: Godzilla and Godzilla Raids Again

I’ve already written extensively on Godzilla’s origin tale in my review of the Blu-ray of the original. Here is the “on-the-go” version:

In 1954, Tomoyuki Tanaka, a producer at Japan’s powerful Toho Studios, needed a movie to go into production after co-financing on a war film collapsed. Seizing on the recent popularity in Japanese cinemas of the original King Kong and The Beast From 20,000 Fathoms, and referencing a recent flare-up over fear of atomic power because of an incident where a Japanese fishing boat was caught in the fallout from the Bikini Atoll test, Tanaka devised the concept of a radioactive giant beast coming ashore and devastating Tokyo. Special effects wizard Eiji Tsubaraya devised the design of the monster (originally intended as a sort of “aquatic gorilla,” hence the monster’s Japanese name, Gojira, a portmanteau of the words for “gorilla” and “whale”) and the extensive miniature special effects. Rising dramatic director Ishiro Honda handled the human action. Musical maestro Akira Ifukube crafted the thundering, doom-filled score, and also created the monster’s distinctive roar: the sound of a resin-coated glove rubbing the strings of a contrabasso.

Honda, Tanaka, Tsubaraya, and Ifukube are collectively known as the “Godzilla Fathers”: the four were instrumental in shaping Godzilla into the phenomenon we know today, and each remained with the monster for many years, seeing the numerous alterations the series underwent as it shifted from a tale of atomic doom into a multifaceted science-fantasy franchise. Ishiro Honda and Eiji Tsubaraya became an almost inseparable team in Japanese fantasy films from the late ’50s until Tsubaraya’s death in 1970, their work together forming a distinct “Honda-Tsubaraya” canon.

Honda, Tanaka, Tsubaraya, and Ifukube are collectively known as the “Godzilla Fathers”: the four were instrumental in shaping Godzilla into the phenomenon we know today, and each remained with the monster for many years, seeing the numerous alterations the series underwent as it shifted from a tale of atomic doom into a multifaceted science-fantasy franchise. Ishiro Honda and Eiji Tsubaraya became an almost inseparable team in Japanese fantasy films from the late ’50s until Tsubaraya’s death in 1970, their work together forming a distinct “Honda-Tsubaraya” canon.

Godzilla (Gojira) hit theaters in Japan in November 1954, the same year as The Seven Samurai, and turned into a smash success. The film cost thirty times more than the average Japanese production, but Toho’s risk paid off. The film broke the record for opening-day ticket sales in Tokyo, and approximately 9.6 million people saw the film during its initial run.

No one in Japan had seen a film like it before; although special-effects films were common, they were almost always war spectacles. Since Japan had no military, effects artists like Eiji Tsubaraya had to create military tech using miniatures. The work in Godzilla, however, created a stunning monster and scenes of devastation that gnawed deep at people for whom World War II was still a fresh memory. The devastating nuclear message struck a chord with a country that was only beginning to grapple publicly with their tragic part in the start of the nuclear arms race. Godzilla opened up eyes, and for some it was a powerful awakening.

Star Akira Takarada, who was at the beginning of his long successful career with Godzilla, later recalled: “When Godzilla destroyed the big clock [in the movie], it was a metaphor for an alarm telling us we are running out of time. Forty years have passed, but deep down the message is the same. Mankind woke Godzilla, and today we have similar issues: air pollution, the ozone layer. That is also Godzilla. They’re the same in that they were all brought on by mankind.”

Yet … there was an ineffable compassion for the frightful atomic monster that hinted at what would come. Takarada took notice of this: “When I first saw Godzilla at the studio screening, I couldn’t help crying when I watched Godzilla become a skeleton. I thought, ‘Why did mankind have to punish Godzilla like that?’ … Mankind seemed like a bigger villain than Godzilla, and I felt sorry for him. I think sympathy for him still exists today. If Godzilla were truly evil, people wouldn’t have loved him so much.”

Commerce dictated a sequel, and a sequel fast. In the 1930s–1950s, sequels were usually quickie affairs done cheaper than the original to strike while the property was still on the public’s mind. The sequel to Godzilla, which reached theater screens a mere six months after the first, followed this pattern.

Commerce dictated a sequel, and a sequel fast. In the 1930s–1950s, sequels were usually quickie affairs done cheaper than the original to strike while the property was still on the public’s mind. The sequel to Godzilla, which reached theater screens a mere six months after the first, followed this pattern.

Godzilla Raids Again (1955) is one of the more forgotten Godzilla films in the West. Director Ishiro Honda, a key part of the success of the first movie, was already assigned to another project, so a less visionary director, Motoyoshi Oda, handled the film with aggressive blandness.

Godzilla Raids Again pits Godzilla against another monster for the first time, the spiky Ankylosaurus-like beast Anguirus. The film contains a few fine pieces of special effects staging, but significantly less thought, passion, and time went into its production. The human factor Honda brought to Godzilla is absent from the non-effects scenes of Godzilla Raids Again, making it a chore to get through when the focus is away from the often impressive battle sequences between an animalistic Godzilla (who moves with stunning swiftness at times) and feisty Anguirus. Godzilla Raids Again made money, but didn’t impress audiences. That appeared to be the end of Godzilla on movie screens.

Godzilla, King of the Monsters! and the Japanese Science-Fiction Boom (1956–1961)

Indeed, Godzilla would not return in a new film for six years. But those middle years were busy for Godzilla in other parts of the world, and busy for the Japanese film industry setting up a new universe of magnificent monsters and strange aliens as the tokusatsu (special effects) genre exploded.

In the United States, a burgeoning interest in importing Japanese films because of the success of the movies of Akira Kurosawa and Hiroshi Inagaki brought Godzilla (yes, the monster’s English name comes from Toho Studios, not the U.S. distributors) to the attention of Hollywood. A group of investors purchased the U.S. rights to Godzilla for a modest $25,000. Giant radioactive monster films were making cash for B-movie studio units and small production companies, and the investors recognized in Godzilla something they could re-craft to appeal to American teenagers who enjoyed movies like Them! and The Beast from 20,000 Fathoms.

In the United States, a burgeoning interest in importing Japanese films because of the success of the movies of Akira Kurosawa and Hiroshi Inagaki brought Godzilla (yes, the monster’s English name comes from Toho Studios, not the U.S. distributors) to the attention of Hollywood. A group of investors purchased the U.S. rights to Godzilla for a modest $25,000. Giant radioactive monster films were making cash for B-movie studio units and small production companies, and the investors recognized in Godzilla something they could re-craft to appeal to American teenagers who enjoyed movies like Them! and The Beast from 20,000 Fathoms.

Thankfully, Godzilla’s U.S. handlers did better with their purchase property than anybody had any right to expect. Director-editor Terry Morse oversaw a respectful re-working of the Japanese film with new footage of a pre-Perry Mason Raymond Burr starring as an American reporter who arrives in Japan in time to witness Godzilla’s attack. The re-fashioned film was released in 1956 as Godzilla, King of the Monsters! and was a substantial hit not only in the U.S. (a $2 million gross during its opening run) but also worldwide.

Although Godzilla, King of the Monsters! is a lesser version of the Japanese Godzilla, the power of the original shows through, and the new scenes were written, directed, and acted with a sobriety and honesty that befits the tale. Although the U.S. scenes were shot on a tight schedule of only three days (Burr liked to claim he shot all his scenes in a straight twenty-four hours), they feel as if everybody involved cared about what they were doing.

More important than the quality of Godzilla, King of the Monsters! is how it played internationally. This was the version of the film that traveled the globe and made Godzilla a success outside its home country. By Americanizing the film, the U.S. producers created a more easily palatable product for foreign markets of the 1950s. Even Japan released Godzilla, King of the Monsters! to theaters, rather clumsily cropping it to make it seem like a CinemaScope film.

While the U.S. version raked in revenue across the world, Toho Studios turned not toward more Godzilla, but more monsters in general, igniting the kaiju (“monster”) genre. They also turned to color, which was beginning to grow as the new spectacle for tokusatsu cinema. Director Ishiro Honda returned to giant monsters with Rodan in 1956, an excellent film about two Pteranadon-like flying creatures emerging from a volcano. Toho then leaped into pure science-fiction spectacles from the Honda-Tsubaraya-Tanaka-Ifukube team (hereafter HTTI) with The Mysterians (1957) and Battle in Outer Space (1959), both massive alien invasion/space opera epics with copious special effects that still dazzle. Although influenced by the U.S. model of alien invasion movies, the Japanese versions were more colorful, expensive, and strange. The HTTI team stumbled a bit with Varan (1958, released in the U.S. in severely altered form as Varan the Unbelievable), the last of their films in black and white. But when they reached Mothra (1960), a crazy movie with a giant moth and miniature fairies and musical numbers and famous comedians, it was clear that Japan had developed their own peculiar, fantasy-slanted take on what started with as an imitation of the U.S. documentary-style of science-fiction.

While the U.S. version raked in revenue across the world, Toho Studios turned not toward more Godzilla, but more monsters in general, igniting the kaiju (“monster”) genre. They also turned to color, which was beginning to grow as the new spectacle for tokusatsu cinema. Director Ishiro Honda returned to giant monsters with Rodan in 1956, an excellent film about two Pteranadon-like flying creatures emerging from a volcano. Toho then leaped into pure science-fiction spectacles from the Honda-Tsubaraya-Tanaka-Ifukube team (hereafter HTTI) with The Mysterians (1957) and Battle in Outer Space (1959), both massive alien invasion/space opera epics with copious special effects that still dazzle. Although influenced by the U.S. model of alien invasion movies, the Japanese versions were more colorful, expensive, and strange. The HTTI team stumbled a bit with Varan (1958, released in the U.S. in severely altered form as Varan the Unbelievable), the last of their films in black and white. But when they reached Mothra (1960), a crazy movie with a giant moth and miniature fairies and musical numbers and famous comedians, it was clear that Japan had developed their own peculiar, fantasy-slanted take on what started with as an imitation of the U.S. documentary-style of science-fiction.

In North America, the second Godzilla film made its lurching way to theaters, and thanks to idiotic marketing moves, made zero impression on U.S. audiences. Originally, the investors who picked up Godzilla Raids Again planned to plunder the film for only its special effects and create an entirely new story around the footage with English-speaking actors. The project, titled The Fire Monsters, almost happened — but its production company, AB-PT Pictures, went under before the script went before the cameras. Godzilla Raids Again eventually ended up with producer Paul Schreibman, one of the original U.S. investors on Godzilla, King of the Monsters! Schreibman made a distribution deal with Warner Bros. Godzilla Raid Again received a cheap “Americanization” that consisted of a rancid dubbing job, replacement library music, and a slew of hilariously mismatched stock footage.

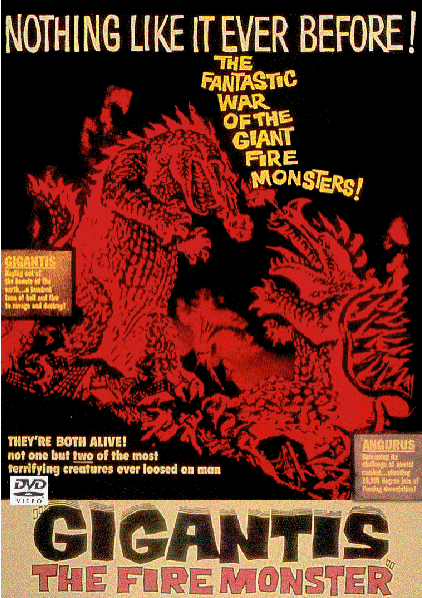

Worst of all — both for the movie and its box-office prospects — Paul Schreibman decided to take the name of its star off the film! The movie was released in 1958 as Gigantis, The Fire Monster, with all mentions of “Godzilla” excised from the dubbing, as well as any reference to the earlier film. Schreibman apparently believed he could pass this off as “new” monster, instead of capitalizing on the name value of the previous movie. Guess what happened? That’s right, nobody bothered to show up to see Gigantis, The Fire Monster. After a few showings on TV in the ‘60s, the movie vanished from the U.S. for decades, becoming a semi-lost Godzilla movie for Western audiences. It’s now on DVD in North America, both in its Godzilla Raids Again version and the gut-bustingly bad U.S. hack job.

Godzilla Becomes a Celebrity: King Kong vs. Godzilla

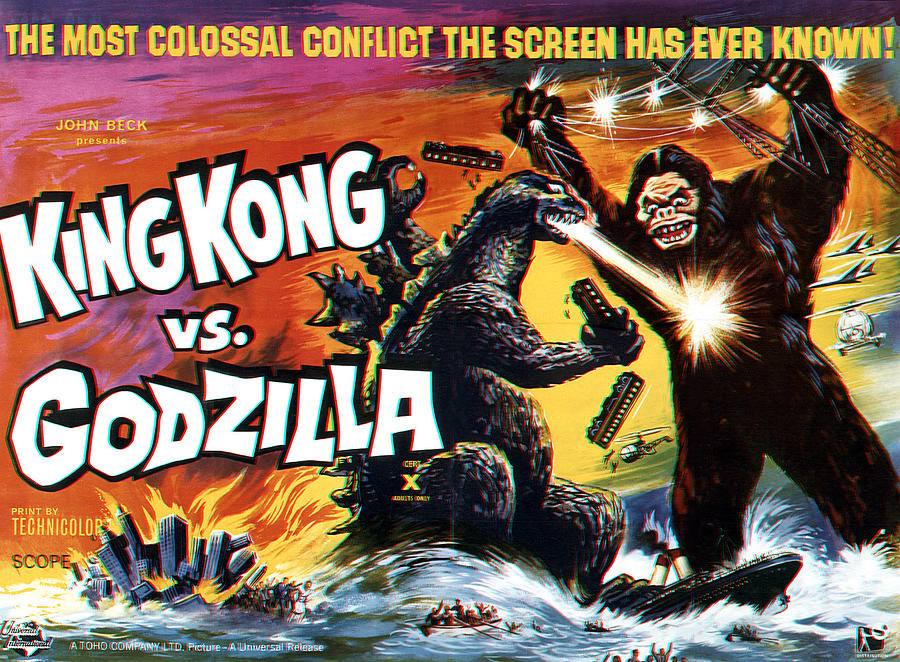

By 1962, Toho Studios was ready to bring Godzilla back to screens. The Toho Special Effects department had now mastered their distinct style, and with a string of SF and monster-related hits from the HTTI team and the popularity of Godzilla growing worldwide, the Toho front office was eager for a splashy color and widescreen return of the Big-G. They delivered a monster smack-down with a title never rivaled in crossover history: King Kong vs. Godzilla.

By 1962, Toho Studios was ready to bring Godzilla back to screens. The Toho Special Effects department had now mastered their distinct style, and with a string of SF and monster-related hits from the HTTI team and the popularity of Godzilla growing worldwide, the Toho front office was eager for a splashy color and widescreen return of the Big-G. They delivered a monster smack-down with a title never rivaled in crossover history: King Kong vs. Godzilla.

How did Toho end up with the rights to the famous U.S. super-simian? Unfortunately, it’s a sad story of a producer named Jerry Beck doing an end run around special effects master Willis O’Brien, who handled the effects for the original King Kong and ranks as one of the giants of movie magic. O’Brien always struggled finding backing for his own projects, but when he proposed King Kong vs. Frankenstein, he got the interest of Jerry Beck, who promised to shop the project around the studios. The idea eventually morphed into King Kong vs. Prometheus, but Beck actually cared not a fig for O’Brien’s idea or creative passions; Beck wanted the rights to King Kong so he could sell them off. Toho studios leaped at the chance, and Beck sold the King of Skull Island behind O’Brien’s back. In exchange, Beck got exclusive rights to distribute the film in the U.S.

King Kong vs. Godzilla was an enormous hit in its home country in 1962, and remains one of the highest grossing Japanese films of all time. The movie does no favors for King Kong, who looks rather shabby and goofy, but does amazing things for Godzilla. Visual effect supervisor Eiji Tsubaraya wanted to shift Godzilla from a bleak interpretation and make the monster more light and fun. Although not the direction that director Honda wanted to go — he preferred serious drama about humanity uniting to face a common threat — it was a way to transform Godzilla into a franchise figure. Godzilla in King Kong vs. Godzilla is still a nasty bit of business when facing down the military, but the monster now sported “attitude,” striking poses and genuinely seeming to enjoy wreaking havoc. In the confrontations with Kong, Godzilla pulls out Sumo wrestler moves and does taunting and teasing gestures. The personification of Godzilla had begun.

King Kong vs. Godzilla is a deliberate comedy — at least in the Japanese version that has never seen an official release in the U.S. It’s the only Godzilla film made intentionally for laughs. Instead of a grim tale of atomic power, King Kong vs. Godzilla plays as light satire about Japanese media culture in the early ‘60s, particularly television. North American viewers only familiar with the U.S. re-cut have no idea how hilarious the film is, or that the monster fights are intentionally meant for laughter and rah-rah cheering. There’s no way that King Kong swinging Godzilla around by the tail or trying to stuff a tree down his enemy’s mouth was meant as anything other than appealing silliness.

King Kong vs. Godzilla is a deliberate comedy — at least in the Japanese version that has never seen an official release in the U.S. It’s the only Godzilla film made intentionally for laughs. Instead of a grim tale of atomic power, King Kong vs. Godzilla plays as light satire about Japanese media culture in the early ‘60s, particularly television. North American viewers only familiar with the U.S. re-cut have no idea how hilarious the film is, or that the monster fights are intentionally meant for laughter and rah-rah cheering. There’s no way that King Kong swinging Godzilla around by the tail or trying to stuff a tree down his enemy’s mouth was meant as anything other than appealing silliness.

Oh yes, Jerry Beck’s U.S. version, eventually released through Universal International Pictures … what a fiasco. The Japanese version wouldn’t have worked well in the U.S. at the time; it was too ingrained in the comedy of its culture. But Beck’s changes made the movie into the wrong kind of joke. Incredibly boring and condescending footage of an American newscaster and his scientific commentator interrupt the flow of the story continually, with large portions of the Japanese comedy scenes dumped out and the dubbing script killing what does appear. The new footage appears horrendously cheap as well, which degrades the look of the overall film. Most of Ifukube’s incredible music was excised and replaced with library music that overuses the already overused sting from The Creature from the Black Lagoon — again and again and again.

Although King Kong vs. Godzilla in its U.S. incarnation did excellent business when released to theaters in the summer of 1963 and on its subsequent TV broadcasts, it has turned into too much of a punch line in North America and is often used to dismiss the whole Godzilla series as camp junk. (Apparently, these people have never seen Godzilla vs. Megalon. Now that is how you do camp.) The Japanese original needs to receive a stateside release one day.

For both Japan and the rest of the world, Godzilla had entered a new era: a 1950s atomic bringer of doom from a serious black and white movie was now a colorful and red-hot property ready for superstardom.

NEXT: The Golden Age (1963–1968)

Ryan Harvey is one of the original bloggers for Black Gate, starting in 2008. He received the Writers of the Future Award for his short story “An Acolyte of Black Spires,” and his stories “The Sorrowless Thief” and “Stand at Dubun-Geb” are available in Black Gate online fiction. A further Ahn-Tarqa adventure, “Farewell to Tyrn”, is currently available as an e-book. Ryan lives in Costa Mesa, California where he works as a professional writer for a marketing company. Occasionally, people ask him to talk about Edgar Rice Burroughs or Godzilla in interviews.

Interesting to learn that they decided to go straight comedy with just the third installment of the franchise. The Universal monsters generally got three or four serious installments before they met Abbott and Costello.

I’ve always heard that there were two endings to King Kong vs. Godzilla: the Japanese version has Godzilla winning, while the U.S. release has the Hollywood-grown simian champ come out on top. I haven’t seen the film since I was a kid and can’t recall if that’s true or just a pop-culture myth?

That’s indeed a long-running pop-culture myth, Nick. A lot of reputable sources have repeated it as if it were the truth. But although the U.S. version changes just about everything about the Japanese version, the ending is one thing they didn’t change. The two monsters grapple, fall into the sea, and vanish for a few brief moments. (The U.S. version sticks in some footage of houses collapsing taken from The Mysterians at this point, for no reason at all except that they also had the rights to that film.) Then, Kong emerges, swimming out to sea. The suggestion is the fight is a draw. Kong is either fleeing Godzilla’s turf, or is victorious and going home.

The only difference between the two (aside from that gratuitous destruction stock footage) is that the Japanese version adds a Godzilla roar to the Kong roar over the word “End” on screen.

Great stuff as usual! Will your purview be extended as far as King Kong Escapes? How about the Heisei Rebirth of Mothra films?

Takarada is right about the ending of Godzilla – it’s strangely affecting considering all the destruction wrought. As destructive as Godzilla is in that movie he never really comes across as evil, but simply as a force of nature passing through. Killing him is a Pyrrhic victory because it turns out that the answer to defeating a walking nuclear blast is to create something that is actually worse than nuclear weapons.

Sorry, Joe, but to keep this from spiraling out of control, I’ve chosen to strictly limit the main discussion to the official Godzilla films. Believe me, I’d love to fly off into talking about Dogora (that is one weird movie), War of the Gargantuas, and Daiei’s wonderful “Daimajin” trilogy, but I have to narrow the other films outside of Godzilla to mentions.

I’ll deal with King Kong Escapes briefly, because its production is closely tied to the production of Ebirah, The Horror of the Deep (Godzilla vs. The Sea Monster).

An interesting history. I’m really looking forward to the next part. I love Mothra vs. Godzilla, Giddarrah the Three Headed Monster, and Godzilla vs. Monster Zero.

Those three are the lead off in the next post, Amy, since they are sort of the “Great Trio” of Godzilla’s history.

Fair enough — otherwise you’d be talking about Atragon and Orochi and eventually you’d end up at The Super Inframan which isn’t even Japanese …

Well, I have written about Atragon before, but not at Black Gate.

Let’s not forget Yongary, The Monster from the Deep, South Korea’s 1967 entry into the monster madness of the period. And of course, the bizarre Pulgasari, a North Korean giant monster film whose director was kidnapped by Kim Jong-Il just so he could make movies for him. (The director later escaped during a Vienna film festival.)

Why so you did! And that led me to the article about Battle in Outer Space, which led me ever further down the rabbit hole …

When you end up at Space Amoeba, Joe, give a shout and I’ll pull you back up.