H.P. Lovecraft, A. Merritt, and Appendix N: Advanced Readings in D&D

We’re drawing closer to the end of Gygax’s famous Appendix N, the list of influences and recommended reading he included at the back of the D&D Dungeon Masters Guide.

We’re drawing closer to the end of Gygax’s famous Appendix N, the list of influences and recommended reading he included at the back of the D&D Dungeon Masters Guide.

Over at Tor.com, Tim Callahan and Mordicai Knode continue their tireless trek through the entire list, sampling a little bit of each writer and generously sharing their impressions with us, while here at Black Gate we continue to appreciate and critique their columns. Since that’s a heck of a lot easier than actually trying to read along with such a massive project. Makes me tired just to think about it. Seriously, I need a bit of a lie down.

In the last few weeks they covered one of the most popular fantasy writers of the 20th Century — indeed, one of the most popular writers to pick up a pen, period — and a relatively obscure short story writer who was ignored for virtually his entire life, until a tiny press in Sauk City, Wisconsin, decided to make it their mission to return all of his works to print shortly after his death. Yes, we’re here today to discuss A. Merritt and H.P. Lovecraft, respectively.

Let’s start with Lovecraft. Mordicai kicks things off in fine fashion:

The guy basically invented contemporary horror — besides splatter and slasher, I suppose — and you can’t really talk about him without a sort of gleeful enthusiasm. Or at least, I can’t.

Uncaring alien godthings and cults of fishpeople get all the attention, but the stories that stick with me are the ones that get a little more surreal. Don’t get me wrong: At the Mountains of Madness, Call of Cthulhu, The Dunwich Horror, The Shadow Over Innsmouth… there are a reason that these stories are at the forefront, as the juxtaposition of modern man with truly unknowable forces is a ripe category…the ensuing cosmic creepfest and insanity in response to a nihilistic and uncaring universe might be seen as Lovecraft’s thesis.

That said, for me it is the odder tales, like The Dream-Quest of Unknown Kadath, that kick it up a notch. Hordes of cats, friendly conversations with cannibal ghouls, trips to the moon, evil ticklers, and terrifying plateaus that only exist in dreams? Yes please! I’m going to go on a limb and say that I see a little Randolph Carter in some of my favorite protagonists. Dale Cooper from Twin Peaks, I’m looking at you…

While I’m a devoted fan of Lovecraft’s longer and most famous works — I consider “The Shadow out of Time” to be one of the finest pieces of fantastic fiction ever written — there’s no question that his Dream-Quest tales are equally worthy of attention. A tip of the hat to Mordicai for not taking the easy route.

I was very curious to see what Tim thought, as frankly Tim’s been a little out-to-lunch with these last few classic writers (even admitting he’d never heard of Manly Wade Wellman before beginning this project). But I’m willing to forgive all if Tim can bring his A-game to a big-hitter like Lovecraft.

Here’s Tim’s response to Mordicai:

Here’s Tim’s response to Mordicai:

This is going to be fun, because I have no idea what you’re talking about. Here’s the thing: I never read a single H. P. Lovecraft story before 2012.

Oh, aaaargh. Come on. Bloody hell.

All right. Deep breaths. I’m over it. At least with a tabula rasa, we’ll get to experience the full impact of exposure to Lovecraft for the first time, right?

Right, as it turns out. Here at least, Tim does not disappoint:

It doesn’t matter if you understand that Lovecraft deals in the unknowable and an overwhelming sense of despair and dread. What matters is that when you read his stories, you feel it. Reading Lovecraft fills you — well it fills me, at least — with that sense of uncertainty and dread and anxiety…

And what’s perhaps creepiest of all, as I sit here and pretend to be a Lovecraft expert after only reading a few stories (including “The Shadow out of Time”), is that Lovecraft seems less like a storyteller and more like a historian or an archeologist of the cosmically terrible. He’s in touch with forces beyond our reckoning and he’s conveying that truth to us. That’s the game he’s playing as a writer, but he’s damn good at it.

Well said, Tim. I can almost forgive you for spacing on Manly Wade Wellman.

As I alluded above, outside a certain fame in Weird Tales, one of the more marginal pulp magazines in terms of circulation, Lovecraft was virtually ignored in his lifetime. Even when he managed to break out of Weird Tales with a major work — as he did with “At The Mountains of Madness” and “The Shadow Out of Time,” both of which first appeared in Astounding Stories in 1936 — he was generally scorned.

Early science fiction readers did not appreciate Lovecraft’s brand of weird horror seeping into their magazine, and they expressed their displeasure in the Astounding Letters column. Lovecraft never appeared in Astounding (or any SF pulp, really) again.

Early science fiction readers did not appreciate Lovecraft’s brand of weird horror seeping into their magazine, and they expressed their displeasure in the Astounding Letters column. Lovecraft never appeared in Astounding (or any SF pulp, really) again.

However, unlike 98% of pulp writers (and indeed, most other Appendix N authors) virtually everything Lovecraft ever wrote — including his obscure early fiction, collaborations, letters and poetry — is currently in print. And has been continuously in print for pretty much four decades. How’s that for a literary fairy tale.

Depending on your preference, you can collect Lovecraft in a variety of different ways. Arkham House, founded in Sauk City, Wisconsin in 1939 by August Derleth and Donald Wandrei to bring Lovecraft’s work to a larger audience, has indeed kept his work in print for nearly 75 years now, and if you’re a collector the three Arkham volumes you need are The Dunwich Horror and Others, At the Mountains of Madness and Other Novels, and Dagon and Other Macabre Tales, which together include all of his solo-authored fiction.

If you’re not a collector, there are a few inexpensive one-volume editions in print, including H.P. Lovecraft The Complete Fiction, a handsome discount hardcover you can find at most Barnes & Nobles.

You can also find virtually all of Lovecraft’s work in paperback. He’s been collected in several handsome editions through the years, starting over 65 years ago with The Dunwich Horror (1945, Bart House), and one of my all-time favorite vintage paperbacks, the 1947 Avon Books The Lurking Fear and Other Stories (pictured above), with an appropriately ghoulish cover by A. R. Tilburne.

In terms of more recent volumes, I highly recommend the Ballantine paperbacks, many of which were part of Lin Carter’s fabulous Ballantine Adult Fantasy line. Most were reprinted through the 70s, including The Dream-Quest of Unknown Kadath (1970, cover at right), The Doom that Came to Sarnath and Other Stories (1971, cover here), and The Horror in the Museum and Other Tales (1975, cover here).

Since roughly the late 80s, Del Rey has kept the complete works of Lovecraft in print in half a dozen trade paperback volumes which you can find in most bookstores, including The Best of H. P. Lovecraft (1987), Dreams of Terror and Death: The Dream Cycle of H. P. Lovecraft (1995), The Road to Madness (1996), and Tales of the Cthulhu Mythos (1998), all with covers by John Jude Palencar.

The Watchers Out of Time (2008) includes fifteen story fragments by Lovecraft that were completed by August Derleth, and The Horror in the Museum (2007) is a collection of those tales he revised for publication by other authors.

The Watchers Out of Time (2008) includes fifteen story fragments by Lovecraft that were completed by August Derleth, and The Horror in the Museum (2007) is a collection of those tales he revised for publication by other authors.

Read Tim and Mordicai’s complete Lovecraft article here.

Next, they turn to one of the most famous fantasy authors of the early 20th Century, a man whose novels sold in the millions in the 1930s and 40s, but who is virtually forgotten today: A. Merritt.

Before we get into Merritt, I want to admit up front that I’ve never been able to read him.

I’ve tried. But even as a young teen, I found his prose wooden, and his characters flat. And believe me, I had a high tolerance for wooden prose at fifteen.

If I couldn’t hack Merritt, I pretty much expect Mordicai and Tim to eat him alive. At this point, in fact, after their rather cold dismissal of gifted writers like Manly Wade Wellman, Fredric Brown, and L. Sprague de Camp in earlier articles, I’ll be rather dumbfounded if they give Merritt a pass.

Of course, I haven’t really sampled all that much of Merritt (I read The Face in the Abyss, and that pretty much did it for me), so I suppose there’s a chance I’ve judged him unfairly. Certainly he was very highly regarded by millions of readers in the pulp era.

But enough preamble. I haven’t peeked ahead to see what Tim and Mordicai thought. So let’s find out together.

Here’s Tim on Merritt’s The Moon Pool, which they describe as “full of ray guns, frogmen and lost civilizations!”

The version I have is a sad attempt to cash in on the popularity of ABC’s Lost. How can I tell? Because the front and back cover mention Lost no less than SEVEN times… The Moon Pool is nothing like Lost. It has about as much to do with Lost as The Jetsons has to do with Star Wars. And The Moon Pool has more imagination in any one chapter than Lost had in any ultra-long and tedious season.

It’s one of the aspects of the novel I like best: the trope of the passage to another realm filled with strange creatures and a mystical civilization is so banal in fantasy fiction and role-playing game adventures that it’s often presented like just going to a strange bus stop or something. But Merritt really pushes the weirdness of the experience…

Well, call me dumbfounded. Tim is far kinder to Merritt than he is to more modern (and, to my mind, superior) writers like Fredric Brown. It looks like Tim and I are safely on opposites side of the critical spectrum.

Well, call me dumbfounded. Tim is far kinder to Merritt than he is to more modern (and, to my mind, superior) writers like Fredric Brown. It looks like Tim and I are safely on opposites side of the critical spectrum.

And here’s Mordicai:

Yeah, no. It is like comparing Mega Shark Versus Crocosaurus to Alien or The Thing. Sure, they all have monsters, but… (Also, I think Lost and Mega Shark Versus Crocosaurus have their place, but like you said, that place is not “compared to a masterwork.”)

You know what it really reminds me of? The classic adventure, The Lost City (Module B4). Weird costumes, masks, drugs, the whole thing, all topped off with a strange monster ruling it all. I had a ton of fun playing that adventure.

Well, I haven’t heard anything by A. Merritt called “a masterwork” in a long time. But I suppose it’s good to see some appreciation for a forgotten pulp master (and a shout out for The Lost City, now that I think about it.)

Tim runs with the dungeon theme as he wraps up the article:

Really, though, the whole thing is totally a dungeon crawl with odd NPCs and surprises and even a love story of the type you might find in a classic D&D adventure where one of the characters falls for the daughter of the alien king.

Moon Pool feels like an ur-text for Dungeons and Dragons, more than most of the books in Appendix N. It’s even full of bad accents!

Read the complete Merritt article here.

A. Merritt wrote eight novels, all fantasy, and their popularity made him one of the highest-paid authors of the pulp era — earning $100,000/year by the early 1940s. The Moon Pool was his first novel; it was originally published in two parts in the pulp magazine All-Story Weekly as “The Moon Pool” (1918) and “Conquest of the Moon Pool” (also 1919).

His other novels were The Metal Monster (1920), The Ship of Ishtar (1924), Seven Footprints to Satan (1927), The Face in the Abyss (1931), Dwellers in the Mirage (1932), Burn Witch Burn! (1932), and Creep, Shadow! (1934).

Many of Merritt’s novels featured recurring protagonists. Walter Goodwin was the square-jawed hero of both The Moon Pool and The Metal Monster, and the more intellectual Dr. Lowell was the hero of both Burn Witch Burn! and Creep, Shadow!.

Legendary artist pulp Virgil Finlay is often associated with A. Merritt, chiefly for his beautiful covers for Famous Fantastic Mysteries, including Creep, Shadow!, and his interiors for The Ship of Ishtar. See those, and more samples of his work, in Robert Garcia’s recent Finlay article here at Black Gate.

Legendary artist pulp Virgil Finlay is often associated with A. Merritt, chiefly for his beautiful covers for Famous Fantastic Mysteries, including Creep, Shadow!, and his interiors for The Ship of Ishtar. See those, and more samples of his work, in Robert Garcia’s recent Finlay article here at Black Gate.

While Merritt is largely ignored today (and virtually all of his novels have been out of print for decades), Paizo Press’ Planet Stories Library reprinted The Ship of Ishtar in a handsome new edition in 2009. See Ryan Harvey’s review here.

We last covered Mordicai and Tim’s journey into Appendix N on November 22, when they discussed Manly Wade Wellman and Fletcher Pratt. The list of authors they’ve covered so far includes:

Leigh Brackett and J.R.R. Tolkien

Margaret St. Clair and Andrew Offutt

Lord Dunsany and Philip José Farmer

H.P. Lovecraft and A. Merritt

Manly Wade Wellman and Fletcher Pratt

Fredric Brown and Stanley G. Weinbaum

John Bellairs and Fred Saberhagen

Jack Williamson and Lin Carter

Andre Norton and Michael Moorcock

L. Sprague de Camp, Fletcher Pratt, and Gardner Fox

Roger Zelazny and August Derleth

Jack Vance

Fritz Leiber and Edgar Rice Burroughs

Sterling E. Lanier

Poul Anderson

Robert E. Howard

See the complete list here.

Next up in the Advanced Readings in D&D series: Lord Dunsany and Philip José Farmer.

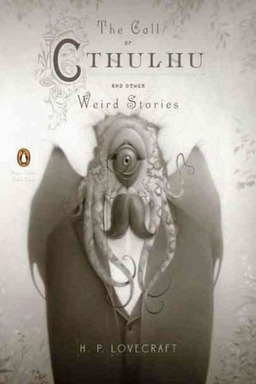

That cover for Penguin’s CALL OF CTHULHU is one of the most nutzoid covers I’ve seen in some time. Beautiful!

Although I’ve heard mixed reports of Merrit’s work and am actually only familiar with two examples of his oeuvre – and the second, properly speaking, is a film based on a book he wrote rather than a work by him – both are excellent. The first appears in Ballantine’s ‘The Young Magicians’. It’s a short story called ‘Through The Dragon Glass’ and a pulp classic in my opinion. The second is ‘The Devil Doll’, a black-and-white classic directed by Todd Browning and based on Merrit’s book, ‘Burn Witch, Burn.’

I haven’t read a lot of Merritt yet — I try; I read one or two novels, then I bounce off; I find Haggard a lot more palatable — but I did make a point of collecting all of the Avon editions (like the Moon Pool pictured) because those covers are so wonderful.

Lovecraft was an amazing author. As much as I love fantasy and science fiction, when I came across a collection of his tales years ago, I found his tales irresistible, though they lined up much more with horror (at least the ones I read). There is something about his style that I want for my own, and I found myself experimenting in certain ways to imitate it in part – something I never attempted with any other author.

He is a master craftsman of suspense. And shock. I would finish a tale and just sit there for a moment thinking, “Wow. What was that?” So creepy, so eldritch. So amazing.

I’m still not big on the idea of “weird” being placed as a description of his work. But from something I vaguely recall, I don’t think he cared that much how his work was labeled; he simply wrote what he imagined, and that often from dreams. I respect authors that just go for it, whether their ideas are popular or accepted by society as a whole. They simply tell the tales they feel they must tell. And look at how well-known and well-loved his works are now…

Merritt didn’t write “Burn, Witch Burn,” Fritz Leiber did.

[…] been chatting a lot about pulp fantasy recently — for example, in our recent explorations of Appendix N, Unknown magazine, escaping our genre’s pulp roots, forgotten pulp villains, Clark Ashton […]

Burn, Witch, Burn! is indeed an A. Merritt novel. The Leiber novel was title Conjure Wife but the film made of it was confusingly called Burn, Witch, Burn!

> That cover for Penguin’s CALL OF CTHULHU is one of the most nutzoid covers I’ve seen in some time. Beautiful!

Isn’t it? There are so many great Lovecraft covers I could have included — any of the many Arkham covers, just for example — but I just had to post that one. I love the Old One in a tux.

Interestingly, it took me a LONG time to find a scan. Amazon no longer lists the book with the cover — it now has a new (and much less interesting) cover, and Amazon is pretending this version doesn’t exist (?). I have no idea why.

I eventually found a few sellers on eBay unloading copies, and ordered one immediately. Of course, I have mutliple copies of Lovecraft’s work at this point, but I couldn’t resist getting this book. Especially since it seems it won’t be available for much longer.

They are pretty cool, JH. I had a Matthews poster up on my bedroom wall (of Elric) when I was teenager.

I stand corrected. Thanks for the clarification.

> The first appears in Ballantine’s ‘The Young Magicians’. It’s a short story called ‘Through The Dragon Glass’ and a pulp classic in my opinion.

Aonghus,

Thanks for the rec! I’ve expressed my indifference with Merritt a few times over the years, and several readers (including the distinguished John C. Hocking) have recommended his short story “People of the Pit” as another classic.

I’m probably not up for another Merritt novel, but I could certainly risk exposure to short story. I’ll add ‘Through The Dragon Glass’ to the list of short stories on my To-Be-Read pile.

> I did make a point of collecting all of the Avon editions (like the Moon Pool pictured) because those covers are so wonderful.

Joe,

Oh, me too. They are marvelous, aren’t they? Merrill in general had tremendous luck with his cover artists. Some of my favorites are the covers to SHIP OF ISHTAR:

http://www.blackgate.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/12/The-Ship-of-Ishtar-full-cover.jpg

And his ghost pirate novel, completed by Hannes Bok, THE BLACK WHEEL:

http://www.blackgate.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/12/The-Black-Wheel.jpg

And of course, the Avon version of DWELLERS IN THE MIRAGE:

http://www.blackgate.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/12/Dwellers-in-the-Mirage.jpg

> I would finish a tale and just sit there for a moment thinking, “Wow. What was that?” So creepy, so eldritch. So amazing.

Matthew,

Yes! That’s exactly how I felt when I first read “The Shadow Out of Time.” Literally mind-blowing stuff.

> I stand corrected. Thanks for the clarification.

Hi Dave,

Perfectly understandable mistake. Oh for the days when Hollywood could steal the title of a bestselling author’s novel, and put it on another book!

It’s like deciding to make a movie out of Neil Gaiman’s AMERICAN GODS, and changing the title to FIFTY SHADES OF GREY at the last minute.

My first introduction to Merritt was in Lin Carter’s Realms of Wizardry — an excerpt from The Metal Monster. (That book also introduced me to Haggard with an excerpt from She.)

My first encounter with Lovecraft was the Penguin paperback of Colour Out of Space. I was probably too young and had no idea what I was in for — the title story scared the bejeebers out of me (and to this day still creeps me out).

I had no idea there WAS a Penguin paperback called The Colour Out of Space. Every time I turn around, there’s another Lovecraft paperback to collect!

Sorry — it was actually the Jove edition; the one with the Rowena painting of a Great Old One from Shadow Out of Time on the cover. Needless to say, it was the cover that drew me.

(Hmmm … Rowena also pulled me to Clark Ashton Smith with her City of the Singing Flame cover.)

This one?

http://www.blackgate.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/12/The-Colour-Out-of-Space.jpg

I don’t have that one either! You’re a thorn in my side this morning, Joe. :_)

Yep, that one exactly. You can see how that could’ve called out to my 6th grade SF-reading self.

(And to clarify, I don’t think there _was_ a Penguin edition. I was just misremembering the publisher.)

Also: My work here is done …

I should quickly add I read it a long time ago, JON! Checking out his longer fiction, it sounds as if ‘Through the Dragon Glass’ was pretty typical but with the added bonus of brevity.

I must check out ‘People of the Pit’.

[…] Sunday I talked extensively about Lovecraft, a propos of his inclusion in the latest round of Advanced Readings in D&D. This morning I invoked his name while discussing Robert Bloch’s Nightmares collection. Now […]

> Yep, that one exactly. You can see how that could’ve called out to my 6th grade SF-reading self.

Oh, indeed. We you aware there was a companion title from Jove, THE DUNWICH HORROR, also with a Rowena cover?

http://www.blackgate.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/12/The-Dunwich-Horror-Rowena.jpg

If I knew of its existence, I must admit I had forgotten. I just found it when I went hunting for THE COLOUR OUT OF SPACE pic.

> I must check out ‘People of the Pit’.

Aonghus,

It’s been reprinted over a dozen times, most recently in the mega-anthology THE WEIRD, edited by Jeff and Ann VanderMeer; James Gunn’s The Road to Science Fiction #2: From Wells to Heinlein; The Screaming Skull and Other Classic Horror Stories, edited by Michael Kelahan; and Masterpieces of Terror and the Unknown, edited by Marvin Kaye.

ISFDB has a complete list:

http://www.isfdb.org/cgi-bin/title.cgi?37542

OK, I think I’ll be needing that edition of Dunwich Horror at some point. Too bad she never (I assume) did something similar for Mountains of Madness.

> OK, I think I’ll be needing that edition of Dunwich Horror at some point.

Oh, me too. I need to track down both of them, in fact.

> Too bad she never (I assume) did something similar for Mountains of Madness.

These are the only two, far as I know. Although there was a Rowena cover on a French-language Lovecraft collection, NIGHT OCEAN:

http://www.blackgate.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/12/Night-Ocean-Rowena.jpg

Pretty sure that was an existing piece of art, though.

[…] last covered Mordicai and Tim’s journey into Appendix N on December 15, when they discussed H.P. Lovecraft and A. Merritt. The list of authors they’ve covered so far […]

[…] in December, in the comments section of my post on “H.P. Lovecraft, A. Merritt, and Appendix N: Advanced Readings in […]