Vintage Bits: BattleTech: The Crescent Hawk’s Inception

Infocom is one of the most revered names in computer gaming history. In fact, for serious collectors of PC games, there’s probably no other company that commands the respect of (or is as collectible as) Infocom.

Infocom is one of the most revered names in computer gaming history. In fact, for serious collectors of PC games, there’s probably no other company that commands the respect of (or is as collectible as) Infocom.

Their heyday was the early 80s, when they released the most famous text adventure ever written, Zork (1980), alongside other classics like Enchanter (1983), Steve Meretzky’s Planetfall (1983), Brian Moriarty’s Wishbringer (1985), and Dave Lebling’s fabulously creepy Lovecraftian scarefest The Lurking Horror (1987).

But my favorite Infocom game came late in their history — indeed, after the company very nearly collapsed following the failure of their ambitious DOS database, Cornerstone, in 1986. By that time, over half of the employees had been laid off and the remnants of the company sold to Activision in a fire sale. For the first time in their history, Infocom turned to outside developers to help fill their production schedule.

It was a desperate move. Infocom had a nearly flawless reputation in the gaming industry, even as late as 1988, and expecting an untested development shop to deliver product that would meet the public’s exceedingly high expectations for an Infocom title was an exceptionally risky bet.

Fortunately, the outside developer they chose was Westwood Studios, who would later go on to develop some of the most successful games of the 90s, including Dungeons & Dragons: Eye of the Beholder (1990), Command & Conquer (1995), Blade Runner (1997) — and who virtually created the real-time strategy (RTS) genre with their groundbreaking Dune II (1992). Their first game for Infocom, and the one that really put them on the map, was one of the best titles Infocom ever released: BattleTech: The Crescent Hawk’s Inception (1988).

Crescent Hawk’s Inception put players in charge of a Mech — a three-story killing machine piloted by a highly-trained Mechwarrior — on the bloody battlefields of the 31st Century. While the EGA graphics are, of course, crude by today’s standard, they were gorgeous eye-candy in 1988, and the ability to move a Mech around the screen and fire off its complement of missiles was thrilling. I know — I spent the first ten minutes of the game time doing exactly that (over and over again).

Crescent Hawk’s Inception was a major departure for Infocom — and, in fact, a pretty innovative step for the whole game industry. For one thing, it was the first title Infocom released to have graphics of any kind (all their previous games, including the bestselling Zork and Enchanter trilogy, were text-based adventure games), and the well thought-out nature of the real-time tactics clearly laid the foundations for the industry’s major leap to a wholly real-time strategy game, the groundbreaking Dune II.

Crescent Hawk’s Inception was a major departure for Infocom — and, in fact, a pretty innovative step for the whole game industry. For one thing, it was the first title Infocom released to have graphics of any kind (all their previous games, including the bestselling Zork and Enchanter trilogy, were text-based adventure games), and the well thought-out nature of the real-time tactics clearly laid the foundations for the industry’s major leap to a wholly real-time strategy game, the groundbreaking Dune II.

Additionally, Crescent Hawk’s Inception was a successful blend of two very different styles of play. Combat was turn-based, like most wargames at the time, allowing you to choose between, say, unleashing a missile barrage, using that nifty new railgun, or letting your weapons cool. Off the battlefield, it played a lot like a role-playing game, allowing you to focus on leveling up your character and daydream of taking on some of the most famous combatants in the sector.

The game opens with 18-year-old Jason Youngblood, son of legendary Mech warrior and war hero Jeremiah Youngblood, tirelessly training in his BattleMech with a team of loyal comrades. The first mission is a simple training exercises that helps familiarize you with your Mech.

It doesn’t stay simple for long, as your training is interrupted by a surprise attack from a squad of enemy Mechs who burst right through the walls of the training ground, intent on killing or kidnapping Jason Youngblood. You and your comrades must beat off the attackers and then discover why you’ve become a target — in the process becoming involved in dark intrigues that involve some of the most powerful Houses in the Inner Sphere.

And that was another fascinating aspect of Crescent Hawk’s Inception. It was based on the popular BattleTech setting, developed and designed by Chicago-based FASA in 1984. BattleTech had a lot going for it: a fast and exciting combat system, a gloriously ambitious design, a loyal fan base — and of course GIANT ROBOTS — but hands down its greatest asset was a brilliantly conceived space opera background.

And that was another fascinating aspect of Crescent Hawk’s Inception. It was based on the popular BattleTech setting, developed and designed by Chicago-based FASA in 1984. BattleTech had a lot going for it: a fast and exciting combat system, a gloriously ambitious design, a loyal fan base — and of course GIANT ROBOTS — but hands down its greatest asset was a brilliantly conceived space opera background.

Set after the collapse of the galaxy-spanning Star League in the 30th Century, BattleTech focused on the civilized Inner Sphere, home to the five great Successor States, all of which claimed to be rightful successor to the rule of the Star League. The action centered on the intrigue, warfare, and political maneuvering between the fives Great Houses, each of which had their own Mechs and styles of fighting.

The BattleTech universe was instantly popular and carefully nurtured by FASA, who recognized the value of the property. It eventually spawned board games, role playing games, collectible card games, toys, miniatures — and a successful line of novels from Roc Books, written by Michael A. Stackpole, William H. Keith, Robert Thurston, Robert N. Charrette, Ardath Mayhar, Loren L. Coleman, Victor Milan, and many others.

As far as I know, the Crescent Hawk storyline is unique to the Infocom games, but is faithful to both the spirit and continuity of the novels and games. It was my first introduction to the world of BattleTech and it succeeded in drawing me in immediately.

As far as I know, the Crescent Hawk storyline is unique to the Infocom games, but is faithful to both the spirit and continuity of the novels and games. It was my first introduction to the world of BattleTech and it succeeded in drawing me in immediately.

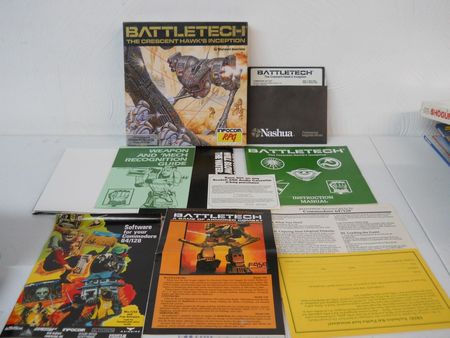

It didn’t hurt that the game was packaged with plenty of fascinating background reading and peripheral materials. Infocom was famous for packing their boxes with widely varying items and goodies (Wishbringer famously included a stone in every box), and Crescent Hawk’s Inception was no exception. The box contains, among other things, detailed background information on the world of BattleTech, a FASA game catalog, and a heavily-illustrated Weapons and Mech Recognition Guide, with artwork from none other than comics great Howard Chaykin. I still remember looking through that Guide and marveling at all the various types of Mechs.

Click on the image at right for a full-size pic of the box contents.

And here’s the game description, from the back of the box:

The 31st century is a desperate time. Five Successor States are hopelessly locked in a mortal struggle for power. In this era of endless war, the powerful, death-dealing BattleMechs are valued higher than human life.

You are 18-year-old Jason Youngblood, and fate has given you a terrible gauntlet to run. Abruptly wrenched from the intense drilling of ‘Mech warrior training, you are plunged into real battle with deadly Kurita warriors. Savage experience is now your unforgiving teacher, and the very survival of The Lyran Commonwealth demands you learn the ruthless precision of battle strategy quickly.

Can you, the son of legendary ‘Mech warrior Jeremiah Youngblood, steel yourself for the greatest challenge of your life?

BattleTech: The Crescent Hawk’s Inception was the first computer game set in the BattleTech universe, but it was by no means the last. Infocom published a second title, also developed by Westwood, just before Activision shut Infocom down for good.

BattleTech: The Crescent Hawk’s Inception was the first computer game set in the BattleTech universe, but it was by no means the last. Infocom published a second title, also developed by Westwood, just before Activision shut Infocom down for good.

BattleTech: The Crescent Hawk’s Revenge had enhanced graphics and an even bigger scope, and proved to be too demanding for older systems — it was released exclusively for the PC in 1990.

Activision made their own stab at a BattleTech game in 1989. MechWarrior, developed by Dynamix and released in 1989, jettisoned the turned-based combat to focus on a first-person role playing game, played out from the cockpit of a Mech. It was an RPG that played like a pure action game, following a five-year story arc, and it was even more successful than The Crescent Hawk series.

After 1990, Activision abandoned the latter line to focus exclusively on MechWarrior, with titles that included MechWarrior 2 (1995), MechWarrior 2: Ghost Bear’s Legacy (1995), and MechWarrior 2: Mercenaries (1996).

In the late 90s, Microprose acquired the BattleTech license from FASA, releasing MechWarrior 3 (1999, developed by Zipper Interactive) and MechWarrior 3: Pirate’s Moon (also 1999).

They also published two excellent MechCommander titles, which returned to the top-down look of the Crescent Hawk games, the first in 1998, and MechCommander 2 in 2001 (both developed by FASA Interactive).

Microsoft eventually acquired FASA in its entirety and took the series in a new direction, starting with MechWarrior 4: Vengeance (2000, FASA Interactive), MechWarrior 4: Black Knight (2001, by Cyberlore Studios), and MechWarrior 4: Mercenaries (2002, Cyberlore).

Microsoft eventually acquired FASA in its entirety and took the series in a new direction, starting with MechWarrior 4: Vengeance (2000, FASA Interactive), MechWarrior 4: Black Knight (2001, by Cyberlore Studios), and MechWarrior 4: Mercenaries (2002, Cyberlore).

That was effectively the end of MechWarrior on the PC. After 2001/2002, Microsoft switched development to the Xbox, to support their fledgling new game machine. In my opinion, the line did not handle the transition well and MechAssault (2002, Day 1 Studios) and MechAssault 2: Lone Wolf (2004, Day 1 Studios) did not really reflect previous glories.

There have been a few BattleTech titles since 2004. MechAssault: Phantom War (Backbone Entertainment) debuted for the Nintendo DS in 2006 and MechWarrior: Tactical Command (Personae Studios) was released just last year for iOS.

Perhaps most promising, the long-awaited MechWarrior Online from Piranha Games, a free-to-play MMORPG, officially launched in September 2013. Check out the cool trailer here.

MechWarrior and its ilk are very fun games and they have become big business. Still, at the risk of sounding like an old man, I miss The Crescent Hawk line created by Westwood Associates and I wonder how things might have turned out differently if Activision had allowed it to continue.

As for Westwood Associates themselves… they eventually merged with Virgin Interactive in 1992, changing their name to Westwood Studios. They were bought by Electronic Arts in 1998 and shut down in 2003. But that’s another story.

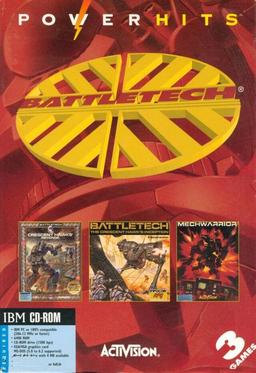

If you’re seriously interested in playing The Crescent Hawk’s Inception and its sequels, I suggest tracking down a copy of the bundled version Activision published in the late 90s as part of their Powerhits line. The bundle also included Crescent Hawk’s Revenge and MechWarrior, which makes it a pretty solid collection.

If you’re seriously interested in playing The Crescent Hawk’s Inception and its sequels, I suggest tracking down a copy of the bundled version Activision published in the late 90s as part of their Powerhits line. The bundle also included Crescent Hawk’s Revenge and MechWarrior, which makes it a pretty solid collection.

Two versions were issued: a big-box original, which included about a dozen floppy disks and packaged up the rulebooks into a single thick volume, and a much slimmer re-issue which contained a single CD and did away with the rules (PDF copies were on the CD). Copies are easy to find on eBay (and occasionally Amazon), but can be a bit pricey, especially the original.

The cover shot at left is the CD version of Powerhits BattleTech, which is the one you’ll want unless your computer can read floppy disks. Click for larger version.

BattleTech: The Crescent Hawk’s Inception was developed by Westwood Associates and released by Infocom in 1988. It was released for IBM, Apple II, Commodore 64, and Amiga machines. The original price was $49.95; copies are available on eBay at prices ranging from $10 – $40. I bought a virtually new PC copy online recently for $14.99.

The most recent Vintage Bits titles we covered here were Lordlings of Yore, Sword of Aragon, and Black Crypt.

Next up: The legendary space role-playing game from Electronic Arts, Starflight.

Fantastic retrospective of the Battletech gaming line, John! I played the 1996-98 series but was too poor to own a computer that would play anything before that date. Still, played the hell out of the tabletop and RPG, so I’ve had my fill of great adventures in the universe. Also, the cover art for Crescent Hawk’s Inception is fantastic! Got to love the Locust!

[…] Pool of Radiance, Dungeon Master, and Dragon Wars. Science Fiction RPGs like Starflight and BattleTech: The Crescent Hawk’s Inception. Adventure games like The Lurking Horror and The Secret of Monkey Island. And tactical wargames […]

Thanks, Scott! It’s funny, while the Battletech board game (now called Classic Battletech, CBT) had a good long run, releases stopped after the property was acquired by WizKids in 2000.

I think WizKids had the right idea — Battletech should have been a miniatures-based game, the way Warhammer was. I believe WizKids tried to take the game in that direction, but by that time existing players resisted, and I don’t know how successful it was.

For a while FanPro kept CBT alive with new releases. Today I think the property is licensed to Catalyst Games, who are still publishing supplements for the board game.

Oh — and you’re right. That cover art is gorgeous!

John, does it give a cover artist credit anywhere in this boxed set?

Oscar Chichoni

Scott — no, it doesn’t. I believe some ports, however, came packed with a poster of the cover art, and it may be possible to find the artist’s name on it.

It’s not in the PC version I bought recently. I have at least two other copies in the cave of wonders (one still in the shrinkwrap, of course), and a few of the Powerhits editions. I’ll check those and see what I can find.

Oscar Chichoni

[…] Our most recent Vintage Bits articles were Sword of Aragon and Battletech: The Crescent Hawk’s Inception. […]

[…] Vintage Bits: BattleTech, The Crescent Hawk’s Inception […]

[…] by Modiphius Entertainment Diaspora by VSCA Publishing Gamma World by TSR BattleTech: The Crescent Hawk’s Inception by Infocom Cold and Dark, from Chronicle City Monster Island, by The Design Mechanism Traveller: […]

[…] like Zork (1980), Enchanter (1983), Planetfall (1983), and the groundbreaking BattleTech game The Crescent Hawk’s Inception. In 1984, legendary Infocom designer Steve Meretzky teamed with Douglas Adams to create The […]