Rejecting the Golden Age: Gareth L. Powell on Escaping Science Fiction’s Pulp Roots

Over at SF Signal, author Gareth L. Powell has issued a call to stop recommending classic SF and fantasy, and start putting newer works in the hands of readers curious about our genres. His comments apparently arise from his experiences talking to a reading group who hadn’t read any SF written in the last 50 years.

Over at SF Signal, author Gareth L. Powell has issued a call to stop recommending classic SF and fantasy, and start putting newer works in the hands of readers curious about our genres. His comments apparently arise from his experiences talking to a reading group who hadn’t read any SF written in the last 50 years.

The only way we’ll escape the legacy of our pulp roots is to promote the innovation, literary merit, and relevance of the best modern genre writing. Some fans will always cling to the ‘golden age’ works of the 1950s, 1960s and 1970s, and I can understand why. They provide a magic door back to the simple pleasures of a simpler world – a world before global warming, oil shortages, terrorism, and economic uncertainty; relics of a world where the future was easily understood, and (largely) American, middle class and white in outlook, origin and ethnicity.

Part of me understands and sympathizes with that need for security. I still draw comfort and enjoyment from those old books. Arthur C. Clarke, Larry Niven, Philip K. Dick… These writers are the elder gods in my personal pantheon; but they are neither the beginning nor the end… being a fan’s a bit like being in a marriage. You have to accept that the person you’re with will mature and change, and you have to embrace that, and change with them in order to keep things fresh…

So, the next time a non-SF reader asks you what they should read, resist the temptation to throw them a copy of Foundation or Slan, and point them instead at something published in the last five years… Give them something modern, and they’re more likely to find characters, ideas and attitudes with which they can relate.

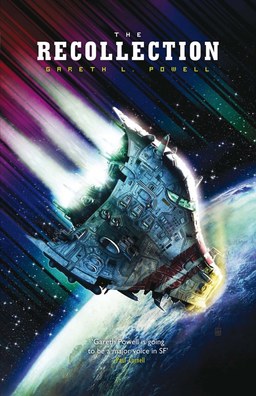

Powell is the author of Silversands, The Recollection, Ack-Ack Macaque and its new sequel, Hive Monkey — which he freely notes employs “the furniture of 1930s pulp literature – Zeppelins, Spitfires, cigar-smoking monkey pilots, evil android armies.”

Read the complete article at SF Signal here.

I’m sure the people of the 50s-70s are relieved to learn how simple their times are.

At least they didn’t have a Twitter feed to worry about.

I agree with Powell in that I wouldn’t give Van Vogt or early Asimov to a potential sci-fi fan anymore than I’d give William Morris to a potential fantasy fan. That being said there seems to be a lot of animus towards the classics these days if not outright dismissal of sci-fi and fantasy’s pulp roots. Experience has proven to me that just because a book’s “better written” doesn’t guarantee it’s a better story.

I’m not sure that this completely applies, but when I hear comments like Mr. Powell’s above, it reminds me of the following quote from C.S. Lewis:

Every age has its own outlook. It is specially good at seeing certain truths and specially liable to make certain mistakes. We all, therefore, need the books that will correct the characteristic mistakes of our own period.

None of us can fully escape this blindness, but we shall certainly increase it, and weaken our guard against it, if we read only modern books. Where they are true they will give us truths which we half knew already. Where they are false they will aggravate the error with which we are already dangerously ill. The only palliative is to keep the clean sea breeze of the centuries blowing through our minds, and this can be done only by reading old books. Not, of course, that there is any magic about the past. People were no cleverer then than they are now; they made as many mistakes as we. But not the same mistakes. They will not flatter us in the errors we are already committing; and their own errors, being now open and palpable, will not endanger us. Two heads are better than one, not because either is infallible, but because they are unlikely to go wrong in the same direction. To be sure, the books of the future would be just as good a corrective as the books of the past, but unfortunately we cannot get at them.

I admit, I’m not much of a science fiction fan these days. My leanings are very strongly toward fantasy and horror, and some of their various sub-genres.

That being said, I used to be a science fiction fan, until about 1990 or so. Since then, I’ve not found much science fiction that interests me, so I can’t honestly follow Powell’s advice. I’m not suggesting there isn’t quality modern science fiction, because in all fairness, I rarely seek out the genre and haven’t in more than two decades, so I honestly don’t have a clue. But upon the few occasions when I have taken a look at modern science fiction, I’ve not found anything of interest. So, on that rare occasion when I want some quality science fiction, I feel like I have to go back to the masters of the genre. I never felt like I outgrew science fiction so much as it outgrew me, or at least moved away from my interests. Maybe that was me changing, or perhaps it was the genre changing, or maybe it was something else altogether, the future becoming the present or some such … I don’t know. But I do know from time to time I miss quality science fiction, and even the handful of Hugo winners and nominees I’ve read from the last few decades have been disappointments to me.

My experience would be pretty much identical to Ty’s – but I wonder how much this is due to my age? And if it is a specific age group that still think fondly of Asimov, Poul Anderson, Harry Harrison et al (I’m guessing 40 – 50 and older) then Powell’s argument is largely redundant. Readership figures for Golden Age SF are still healthy because the middle-aged still buy these books. Anybody under thirty? You could be talking about a completely different demographic.

> That being said there seems to be a lot of animus towards the classics these days if not outright dismissal of sci-fi and fantasy’s pulp roots.

Hi Fletcher,

I don’t know if I’d call it animus so much as ignorance. In any living, growing genre, the new will always push out the old — just as Heinlein and Asimov pushed aside older writers when they showed up. If that weren’t the case, we’d still be reading Wells and Verne.

New readers will naturally gravitate to new writers. As always, I think it falls to us, the fans of classic SF and fantasy, to do a little counter-programming and let modern readers know there are other choices out there.

> They will not flatter us in the errors we are already committing; and their own errors, being now open and palpable, will not endanger us.

James,

Wow — what a great quote!

> But I do know from time to time I miss quality science fiction, and even the handful of Hugo winners and nominees

> I’ve read from the last few decades have been disappointments to me.

Ty,

Interesting you should say that. One of the first SF books I ever read (and loved) was THE HUGO WINNERS, edited by Isaac Asimov, which collected the first decade or so of Hugo-winning short stories and novellas (including “Flowers for Algernon” by Daniel Keyes, “Or All the Seas with Oysters” by Avram Davidson, “That Hell-Bound Train” by Robert Bloch, “The Dragon Masters,” by Jack Vance, “‘Repent, Harlequin!’ Said the Ticktockman,” by Harlan Ellison, and “Time Considered as a Helix of Semi-Precious Stones” by Samuel R. Delany. Man, what a line-up!)

It was a perennial bestseller through the Science Fiction Book Club (and other outlets) for many, many years. It was one of the few books you could assume someone had read when they told you they were a science fiction fan (along with DUNE, THE FOUNDATION TRILOGY, and a small handful of others).

Anyway, every few years a new volume would be released. By the early 90s, those volumes were no longer an event. In fact, they began to sell so poorly that the collections were eventually abandoned altogether. (Can you remember the last time you saw a new Hugo collection?)

I’m not sure what that tells you. Perhaps simply that the heart of the genre is no longer in its short stories and magazines, but in its novels and movies. Perhaps the industry knew how to market anthologies better in the 50s – 70s. Perhaps that the Hugo voting process has become less reliable as fewer voters show interest in short fiction. Or perhaps early SF was simply more accessible, and modern cutting-edge work requires a decades-long immersion in the genre, limiting its broader appeal.

Whatever the reason, winning a short fiction Hugo is no longer the ticket to enduring success and appreciation it once was. They’re simply not celebrated and collected they way they were.

I’m not even sure how many 21st Century Hugo-winning stories I’ve read, but I’d be surprised if it was more than half a dozen. By contrast, I read every Hugo-winning tale from the the 50s through the 70s, most of them multiple times. And I wasn’t alone.

> Readership figures for Golden Age SF are still healthy because the middle-aged still buy these books.

> Anybody under thirty? You could be talking about a completely different demographic.

Aonghus,

I think that’s exactly right. Of course, for many decades teens and young adults made up the bulk of SF purchasers. I don’t have the stats in front of me, but at a guess I think that now that demographic has reversed, and the bulk of genre book buyers are middle-aged.

The situation is analogous to what’s going on today in comics. DC and Marvel market very heavily to a select demographic: men in their 40s, who became comic fans roughly in the late 70s and early 80s. This is why it’s so hard to sell comics aimed at children today.

Is there even SF being written today that’s targeted towards young readers in the way that, say, Heinlein’s juvenile novels were? The only things I can think of offhand are borderline cases like Hunger Games or Paolo Bacigalupi.

(In this case, I mean SF specifically, not SF as a catch-all term for SF/Fantasy/Urban Fantasy/etc. — fantasy seems to be doing quite well.)

Joe,

You know, I’m not sure. I know Tor tried to launch of line of juvenile SF consciously modeled on the Heinlein juveniles over a decade ago, with books by Charles Sheffield, James P. Hogan, and others (I think they called it the Jupiter line). It was quietly discontinued after about half a dozen titles.

I can’t think of a similarly high-profile effort from a major publisher in the last decade, but that doesn’t mean there hasn’t been one.

I think we’re at a kind of a bad time for YA SF, at least anything set in the relatively near future — we’ve gotten to the point where you can’t really do “jetting around the Solar System” books, at least not plausibly, so you either get near-future things falling apart or far-future space opera but nothing in the middle. And space opera has been largely taken over by Star Wars.

Didn’t I say something similar: http://www.blackgate.com/2013/09/09/not-recommending-sff-classics-to-the-young-person-or-novice/

Harold,

Of course you did. But that was back in September, which makes it classic — and we’re ignoring the classics, remember? 🙂

James: That is a brilliant quote!

Joe & John: As far as YA SF, what about John Scalzi? I read Zoe’s Tale a few years ago; I didn’t care for it, but it seemed clearly in the Heinlein-juvenile tradition.

Actually, now I think about it, a couple years ago I reviewed a steampunk YA anthology Kelly Link put together. So there’s that; sf in the form of steampunk must be around for that age range. Actually, at the same time, I was reviewing a book called Steampunk Poe, which was a collection of Poe stories with steampunk illustrations (it worked better than you might think). So I guess I think the classics atill are being read, just being repackaged all the time.

Here’s where I hang my head in shame and admit that the only Scalzi I’ve ever read (aside from his website, which I follow religiously) is Redshirts and The God Engines. Having said that, I don’t think I’ve ever seen Zoe’s Tale _shelved_ as YA — it’s always in there with the rest of the Old Man’s War books in the general SF section.

Gowell’s argument is the same tired PC crap we’ve heard since at least the 80’s about older books. It’s not even worth the time to refute such an infantile article. What is worth talking about, however, is the point raised about the lack of young readers of SF. I didn’t realize that was happening and it is unfortunate because some current authors are just as good as the genre’s past masters (although not for the reasons Gowell thinks). Is it really the case that Star Wars has swept everything else away? My own thought is that adventure novels in any genre that would appeal to young people are becoming scarce in the West for the same reasons we have Ritalin, bicycle helmets, and bans on dodgeball.

Joe H.,

How is zipping around the solar system less plausible than transhumanism or steam punk?

John,

When something calls itself “How to Escape the Legacy of Science Fiction’s Pulp Roots” I can’t help but get a litle riled. It seems like there’s always been an urge among some writers/fans to “legitimize” sci-fi/fant by saying, “Hey, I’m a better artist than those old timers!” and or the concerns of writers from the past are outdated or even offensive. Heck, I think that was the driving impetus of the New Wave movement. I’m all for literary sci-fi/fany (or whatever highfalutin term folks want), but articles like this really exposes the sort of need for people to keep exposing new readers to the best of the older writing.

PS – My biggest shock in reading Powell’s article was that he found a group of sci-fi fans who’d never read either Vinge, Baxter or Gibson. How old were these fans? Vinge and Gibson have been writing for thirty years or more. Seems crazy.

> Gowell’s argument is the same tired PC crap we’ve heard since at least the 80′s about older books. It’s not even worth the time to refute such an infantile article.

Tyr,

Once again, it appears we’re in different corners on this. I actually agree with most of what Powell says.

If we want to bring new readers into the field, we need to give them characters they can readily identify with. And that means giving them newer writers.

> there’s always been an urge among some writers/fans to “legitimize” sci-fi/fant by saying… the concerns of writers from the past are outdated or even offensive.

Fletcher,

I don’t think Powell is deriding the classics, as much as saying that they’re not as effective as they once were at winning new readers.

It’s time to stop being lazy, and just giving 14-year-olds THE FOUNDATION TRILOGY when they ask about SF. Half of the folks interested in SF at that age are girls, and there isn’t a single women (not even a MENTION of a woman) in the first 300 pages of that book. Asimov imagined a future in which women didn’t even exist.

I can tell you right now, my 14 year old daughter would put that down within 10 minutes. She wants to read books with strong female characters, and she doesn’t apologize for it. And I don’t blame her.

John,

I’m actually in agreement with you. Readers do want to see themselves, or at least a part of themselves, reflected in the characters they read about. I agree the books of the past are as often mired in the social conventions of their time as contemporary ones are.

On the other hand, Powell’s line that “Some fans will always cling to the ‘golden age’ works of the 1950s, 1960s and 1970s, … They provide a magic door back to the simple pleasures of a simpler world – a world before global warming, oil shortages, terrorism, and economic uncertainty; relics of a world where the future was easily understood” is either condescending or, going back to your word, ignorant.

In the Fifties you had the Cold War and the ever present possibility of nuclear annihilation. The ‘swinging’ Sixties was characterised by economic unrest, Vietnam and Nixon. The Seventies was just plain seedy. I reckon their very drawbacks was what made them so creatively productive.

SF had such a potent grip on my imagination because I thought that, some day, all of it might come true – this was back in the days when we still thought the galaxy was teeming with different life forms and a decent FTL drive was only a few decades away. We now know Space Opera is no realistic or speculative than LOTR. ‘The Matrix’, ‘BladeRunner’ and Gibson’s books were the first works to acknowledge that ‘modern’ SF – if it wanted to be taken seriously – needed to concern itself with stuff like virtual realities and genetic engineering rather than looking out at the stars. And that was over thirty years ago!

Coming back to SF after an absence of two decades, I was surprised by how little it had changed. A new generation of writers seemed quite happy to produce variations on work with which I was already familiar. ‘The Clockwork Girl’ mimicked Gibson’s structure and style, differing only in that it was even less realistic if nicely written (in general there seemed to be a whole slew of writers using Gibson as a template). At the other end of the spectrum there was enjoyable but standard Space Opera fare like Gary Gibson’s ‘Stealing Light’.

There’s not much point in advocating new writers unless they’re actually doing something new.

John,

I myself found Foundation unreadable so I would hardly blame her. Perhaps hand her a copy of Dune instead?

Besides, it is entirely possible females will be marginalized in the future. Perhaps culture in 2500 AD will look more like Riyadh and not San Francisco?

> As far as YA SF, what about John Scalzi? I read Zoe’s Tale a few years ago; I didn’t care for it, but it seemed clearly in the Heinlein-juvenile tradition.

Hi Matthew,

Apologies, I must have missed your comments yesterday. And you’re right — I didn’t think of Scalzi, but I should have.

In fact, one of the great masterpieces of YA science fiction is H. Beam Piper’s THE FUZZY PAPERS, and Scalzi’s recent updating of that story made it accessible to a whole new generation.

> Actually, now I think about it, a couple years ago I reviewed a steampunk YA anthology Kelly Link put together.

Was that the STEAMPUNK! anthology? I was thinking of getting that for my 14-year old daughter for Christmas — I thought it was time to introduce her to Steampunk. What do you think?

John: Good point about the Fuzzy books! That was a series I loved in my early teens.

And yes, Steampunk! was the anthology I had in mind. As I recall I found it … okay. Actually, it’d probably be better for a 14-year-old; I think my problem was that it seemed overall a bit predictable. Well, a lot predictable. But that’s probably me being old and bitter. The settings were imaginative, there was a conscious interest in telling steampunk stories at the margins of empire, there were lots of lead female characters, and as I remember none of the stories were actively badly written. It’s just that only one or two really seemed to take off and do exceptional things. As I say, a younger reader to whom all this sort of thing is new would probably enjoy it more than I did.

Honestly, looking back over the whole of this comment, it strikes me that I can’t honestly say the book was worse overall than the Fuzzy books, in terms of predictability (or anything else). So, you know, our goalposts slide as we age, and we don’t notice. I’d say yeah, absolutely, as an introduction to steampunk it’s worth a shot.

Actually, I haven’t really commented on Powell’s original article, have I? The thing is, it’s just so scattershot. People upthread have pointed out his odd view of the mid-20th-century as a simpler time, but he also seems to conflate the New Wave with the Golden Age. I mean, Philip K. Dick was aiming at a lot of different things, but I don’t think he was primarily trying for ‘comfort reading.’ And by the 50s, 60s, and 70s, it’s just factually wrong to describe the best genre works as “pulpy and poorly written.” (At least, I can’t imagine how that statement can be justified — how do you apply those terms to Le Guin, Bradbury, Delany, Russ, Ballard?)

That said, his broader point about pushing oneself to read the new, and to look forward to the change and development of genre, is I think well-taken. And I say “look forward to” instead of “accept” deliberately — if you like the form, then you want to see how it develops and changes as much as you want stuff that hits the same buttons in you that you always knew about. Because the new stuff will be working just as well as the old, maybe better. So I tend to agree with his conclusion.

But then again: what you give somebody to read to get into a genre shouldn’t necessarily be what’s new. It should be whatever you figure they’re going to want to read. For some people that’ll be newer things. For others that’ll be older work. It’s all a function of the individual.

So: a mix of “What?” and “I agree” and “Hmm, well …” For whatever that’s worth.

[…] for example, in our recent explorations of Appendix N, Unknown magazine, escaping our genre’s pulp roots, forgotten pulp villains, Clark Ashton Smith’s Martian pulp fiction, and much […]

[…] Rejecting the Golden Age: Gareth L. Powell on Escaping Science Fiction’s Pulp Roots […]