The Shadow of Fu Manchu Falls Upon Me

Without Fu Manchu in my life, I would never have started down the path of penning these articles. One thing I was certain of was that there were no more surprises. I had found every official appearance of Sax Rohmer’s master villain and would, in due course, cover all of them in this blog eventually. So it seems appropriate that in this the year that marks the centennial of the first Fu Manchu novel, my 200th article covers a hitherto unknown official piece of Fu Manchu history.

Without Fu Manchu in my life, I would never have started down the path of penning these articles. One thing I was certain of was that there were no more surprises. I had found every official appearance of Sax Rohmer’s master villain and would, in due course, cover all of them in this blog eventually. So it seems appropriate that in this the year that marks the centennial of the first Fu Manchu novel, my 200th article covers a hitherto unknown official piece of Fu Manchu history.

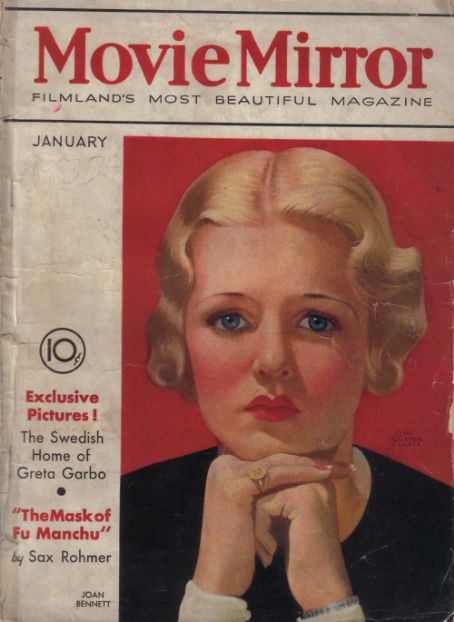

A few weeks ago, I attended Classicon in Michigan and convention organizer, Ray Walsh handed me the January 1933 issue of Movie Mirror with Joan Bennet on the cover. The second feature was The Mask of Fu Manchu by Sax Rohmer. I suspected it was an excerpt from or serialization of the book I was unaware of and found it intriguing that it had eluded both Bob Briney and Larry Knapp, the two foremost Rohmer scholars who have done a phenomenal job of compiling bibliographical information on the author.What the issue actually contained was something far more valuable: an 11-page “fictionization” of the 1932 MGM film starring Boris Karloff and Myrna Loy, fully illustrated with stills from the movie, some of which were quite rare. The adaptation was credited to Constance Brighton, an author I have found no other information concerning which made me suspect the name was a pseudonym.

Those familiar with the film are aware that it is truly a mixed offering. The performances by Karloff and Loy are wonderfully camp as are the sets and props which appear to have influenced the 1960s Batman series. The story roughly approximates Rohmer’s novel with Genghis Khan substituting for the more obscure (and potentially more controversial) El Mokanna. Regrettably, the characterization of Fu Manchu is lacking in the integrity that is the hallmark of Rohmer’s portrayal. This is true Yellow Peril stereotyping at its most offensive.

The film’s ending sees Nayland Smith turn Fu Manchu’s doomsday weapon on the gathered hordes of Asians, Egyptians, Arabs, and Africans in an act of racial genocide. As horrifying as that scene is, it is followed by a closing scene with a comic relief Asian actor with poor teeth, a subservient attitude, and no desire to better himself who is lauded by Smith for knowing his place. Brighton’s adaptation removes the offending final scene and softens the genocidal act by depicting Smith as grimly going about his duty rather than turning into the maniacal racist counterpart to Karloff’s maniacal racist Fu Manchu as the film does. Brighton also soft-pedals on the sado-masochistic streak in Fu Manchu’s nymphomaniac daughter, Fah lo See. However, at times her story is more blunt than the screenplay in discussing the raping and looting that will follow in the wake of the East rising against the West. Brighton does a good job of condensing the story and this heretofore unknown curio is a welcome find for the avid Rohmer collector.

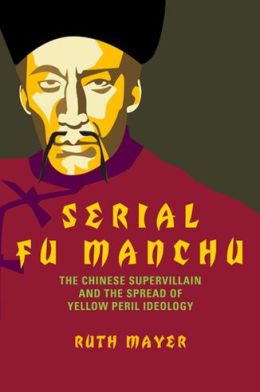

The other unexpected discovery in the past few weeks was a newly published academic work on the proliferation of the Yellow Peril stereotype. Ruth Mayer holds the chair in American Studies at Leibniz University of Hannover. Her book, Serial Fu Manchu published by Temple University Press is a standout among the many studies of Yellow Peril racism that have turned up in the past two decades.

The other unexpected discovery in the past few weeks was a newly published academic work on the proliferation of the Yellow Peril stereotype. Ruth Mayer holds the chair in American Studies at Leibniz University of Hannover. Her book, Serial Fu Manchu published by Temple University Press is a standout among the many studies of Yellow Peril racism that have turned up in the past two decades.

Make no mistake, this is not recreational bed and bathroom reading for most people. Much like a serious academic film study, Mayer’s thoroughly researched work is intended to inform as much as it is to stimulate thought. This is an in-depth look at how the Yellow Peril stereotype took root in the character of Fu Manchu and how the character quickly became an archetype as it spread from one medium to the next until it came to define criminal mastermind tropes while the changing political climate of the Cold War saw the actual characterization descend first into parody and then obscurity.

It must be said there are a few minor errors in the book for those wishing to nitpick, but Mayer knows her topic and this also separates her work from most other Yellow Peril studies which are severely lacking in knowledge on Rohmer or his fiction. It was a very pleasant surprise that I found several of my Rohmer articles cited throughout the work alongside Mayer’s fellow academics.

Lest the suspicious reader suspect this fact has caused me to view Mayer’s work with something other than professional detachment, it should be noted she dismisses my (as well as Cay Van Ash’s) authorized Fu Manchu continuation novels (as well as my other published work, to boot) as little more than derivative fan-fiction. While I was rankled at the description, the author is quite correct that Fu Manchu in the 21st Century is a cult character only embraced by a small body of nostalgia lovers and she is also correct in characterizing me as a writer who wishes to remain lost in the past. As with many of her comments throughout this fascinating book on Sax Rohmer’s most famous creation, she speaks with a blunt honesty that one may not wish to hear, but cannot deny. This is a well-written and important work fully deserving of much attention and accolades for the honest depiction of a racist stereotype and its impact on popular fiction of the past century.

William Patrick Maynard was authorized to continue Sax Rohmer’s Fu Manchu thrillers beginning with The Terror of Fu Manchu (2009; Black Coat Press) and The Destiny of Fu Manchu (2012; Black Coat Press). The Triumph of Fu Manchu is scheduled for publication in April 2014.