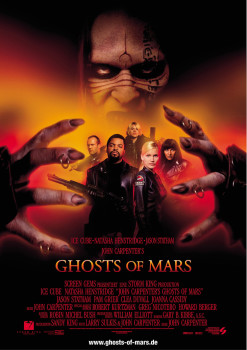

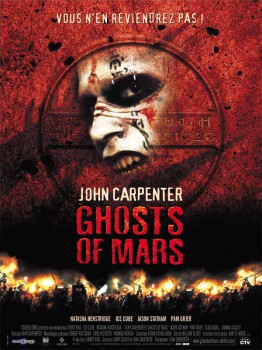

Revisiting the Scene of the Crash: John Carpenter’s Ghosts of Mars

I thought writing two John Carpenter articles in a row was sufficient. I had a strong enough excuse to go two-for-two with Carpenter because of the Blu-ray debuts of Prince of Darkness and In the Mouth of Madness, films that have developed a growing and appreciative fan base. The idea of doing a third article on a John Carpenter film, let alone one on the critically rejected Ghosts of Mars… no that never crossed my mind when I penciled in on my calendar, “Blu-rays for PoD and ItMoM! Write for Black Gate!”

I thought writing two John Carpenter articles in a row was sufficient. I had a strong enough excuse to go two-for-two with Carpenter because of the Blu-ray debuts of Prince of Darkness and In the Mouth of Madness, films that have developed a growing and appreciative fan base. The idea of doing a third article on a John Carpenter film, let alone one on the critically rejected Ghosts of Mars… no that never crossed my mind when I penciled in on my calendar, “Blu-rays for PoD and ItMoM! Write for Black Gate!”

However, enthusiastic comments on both Black Gate and Facebook made it imperative I complete a John Carpenter on Blu-ray trilogy of articles.

(Oh, wait: Assault on Precinct 13 arrives on Blu-ray today. Should I go for four in a row? Or instead do that examination of the Russian animated film The Snow Queen in time for the release of Frozen? I wish more of life’s dilemmas were of this type.)

Watching Ghosts of Mars on Blu-ray was my first time seeing the movie since August 2001, when it managed to hold onto multiplex screens for a week. The horrific opening weekend — coming in ninth place — meant Ghosts of Mars rapidly evaporated into the thin atmosphere, leaving a carbon blast mark people interpreted as the end of John Carpenter’s career. The $28 million science-fiction action/horror film managed a dismal $14 million global gross. Yes, global. Even in a career like Carpenter’s, filled with disappointing box-office returns, Ghost of Mars crashed epically. The critical and audience reaction was also murderous; it seemed unlikely the film would join some of Carpenter’s other financial disappointments like The Thing and Big Trouble in Little China in future fan appreciation.

Yet Carpenter has always had a reputation for being ahead of his time. Was it now time for Ghosts of Mars? Did the passage of twelve years give the film a better sheen, offer more to digest?

There are already some interesting takes on Ghosts of Mars appearing on the ‘net, such as this analysis from John Kenneth Muir (thanks to commenter Golgonooza for bringing this to my attention) and this reevaluation from Phil Noble Jr. at an Alamo Drafthouse website.

When I sat down to watch Ghosts of Mars again, I wrote down three questions to focus my thoughts:

- Did critics (and audiences) of 2001 treat Ghost of Mars too harshly?

- Will Ghosts of Mars eventually achieve semi-classic status in the John Carpenter canon?

- Do I actually enjoy the film?

The answer to these questions are “yes,” “no,” and “uhm, sorta.” To elaborate…

Under-appreciated? Most certainly — for its outrageous ideas, at least

Muir’s lengthy treatise on the film is absolutely worth reading, and I’ll avoid rehashing many of his points and instead cut to what I think is the movie’s most intriguing aspect: John Carpenter used the futurist setting to create a manifestly pro-colonial Western.

Carpenter always wanted to film a straightforward Western, but considering how much he had to fight to get most of his movies funded at all, it makes sense that no backers wanted to toss money at a John Carpenter project in a genre that hasn’t performed steadily since the late ‘60s. So Carpenter took the sneaky route and used Western themes and characters in other genres: Snake Plissken is a Sergio Leone persona to the core, and Assault on Precinct 13 is an urban thriller re-make of one of Carpenter’s favorite Westerns, Howard Hawks’s Rio Bravo. The director has even argued that In the Mouth of Madness is really a disguised Western! (I need to mull that one over.)

The story of Ghosts of Mars can be described in Western archetypes without much deviation. A posse of Texas Rangers ride a train to the mining settlement of Shining Canyon to pick up a notorious outlaw and bring him back to the main settlement to face justice. Once the rangers reach the dusty mining town, they discover it’s deserted. The outlaw, along with a drunk and prostitute, is still in the holding cell in the sheriff’s office. The rangers investigate and discover… the natives are restless! A furious tribe of Indians has gone on the warpath and slaughtered the settlers in revenge for stealing their land. The rangers have to team up with the prisoner and his gang to fight their way back through the town and reach the train when it pulls back into the station.

The story of Ghosts of Mars can be described in Western archetypes without much deviation. A posse of Texas Rangers ride a train to the mining settlement of Shining Canyon to pick up a notorious outlaw and bring him back to the main settlement to face justice. Once the rangers reach the dusty mining town, they discover it’s deserted. The outlaw, along with a drunk and prostitute, is still in the holding cell in the sheriff’s office. The rangers investigate and discover… the natives are restless! A furious tribe of Indians has gone on the warpath and slaughtered the settlers in revenge for stealing their land. The rangers have to team up with the prisoner and his gang to fight their way back through the town and reach the train when it pulls back into the station.

Then, in a throwback to the type of Western you can’t make any more no matter how much money you raise, the rangers decide to return to the town and slaughter all the Indians because “this isn’t their land anymore.”

Now does Ghosts of Mars sound interesting?

To put the story in its Martian perspective: the Texas Rangers are a Martian police force from Chryse, the main city on the planet. The “Indians” are the possessed bodies of the settlers. The original inhabitants of Mars, microscopic organisms accidentally released during an archeological dig, take over the settlers’ minds by entering through their ear canals, turning them into raging, speechless berserkers who paint their faces white and go for extreme body-modification. Except for the matriarchal society that controls Mars, there isn’t much different from the Western version plot description I wrote above. All the designs of the film evoke the Western as well: The outlaw, James “Desolation” Williams (Ice Cube), is held in a cell that looks exactly like the holding cell in any Western sheriff’s office. Shining Canyon might as well be Bronson Canyon where hundred of “B” oaters were shot during the ‘30s and ‘40s. Heroine Lt. Melanie Ballard (Natasha Henstridge) barks out “you’re deputized” to one of the prisoners. The images of the police force stepping down from the train platform and striding into town with guns ready come right from the Wild Bunch. And, of course, the core of the storyline arrives direct from Rio Bravo, making this Carpenter’s return to territory he explored in Assault on Precinct 13 in 1976, where downtown Los Angeles at night stood in for the Wild West.

The indigenous Martians push the movie into strange territory. When Lt. Ballard declares to the survivors aboard the train that they must return to Shining Canyon and annihilate the army of Martian hosts, she delivers the film’s most memorable — and frightening — line: “This is about one thing: dominion. This isn’t their planet any more.”

I don’t recall that line slugging me in the gut in 2001. But now… it makes it clear what Carpenter was attempting. He didn’t just want to make a Western. He wanted to make a purposely retrograde Western, harkening back to the days before 1950’s Broken Arrow opened up the genre to more sympathetic views of Native Americans. Carpenter aimed to make a Western where the Indians played the “bad guys,” and the settlers have no choice except to wipe them out because Manifest Destiny goddammit!

This is the point where Ghosts of Mars moves toward borderline experimental. I do not believe John Carpenter holds any actual malice toward Native Americans. His motivation here was probably similar to the reason Gus Van Sant wanted to attempt a shot-for-shot remake of Psycho: to find out what it’s like to stand in the shoes of long dead filmmakers and imitate what otherwise could not be made today. Carpenter took a discarded Hollywood myth — an unpleasant one — and used science fiction as a disguise to openly play with it, and even make it more extreme. Phil Noble Jr.’s observation is accurate: “[Carpenter] not only got the plot and conventions of his beloved old films down pat; in this film, he’s openly adopted their antiquated attitudes…. Given the ten year break that followed, one has to wonder if he was pissed that no one seemed to have noticed.”

Carpenter’s desire to go this direction appeared as far back as Assault on Precinct 13. The gang members besieging the titular police station attack using stealth tactics right from the 1940s Hollywood version of Apaches. Although Night of the Living Dead gets name-checked as an influence on Assault on Precinct 13, the gang members seem less like zombies and more like a strategic indigenous force, with the precinct standing in for an outpost of the 7th Cavalry. Ghosts of Mars takes the comparison farther toward the old Hollywood Western: the opponents are a true indigenous force, Martian organisms of untold age, who want to wipe out the invaders on their land. The story takes the side of the invaders, and shows no ounce of sympathy for the native Martians.

Carpenter’s desire to go this direction appeared as far back as Assault on Precinct 13. The gang members besieging the titular police station attack using stealth tactics right from the 1940s Hollywood version of Apaches. Although Night of the Living Dead gets name-checked as an influence on Assault on Precinct 13, the gang members seem less like zombies and more like a strategic indigenous force, with the precinct standing in for an outpost of the 7th Cavalry. Ghosts of Mars takes the comparison farther toward the old Hollywood Western: the opponents are a true indigenous force, Martian organisms of untold age, who want to wipe out the invaders on their land. The story takes the side of the invaders, and shows no ounce of sympathy for the native Martians.

By the way, the movie takes place in the year 2176: four hundred years after the Declaration of Independence, but more importantly three hundred years after the Battle of Little Bighorn, a.k.a. Custer’s Last Stand. I don’t believe the year was an arbitrary decision. The train that carries the police to Shining Canyon is called the Yankee. No arbitrary decision there, either.

As if Carpenter sensed he was going too far backwards in one direction, he thrust the movie forward in another and flipped the old Howard Hawks script: the Matronage. Hawks made intense male-bonding films where women played the parts of perky sidekicks. Ghosts of Mars has females dominate the action roles (and Desolation Williams should’ve been a female character as well, now that I think about it) with males taking the roles of second-tier sidekicks and lackeys. Jason Statham plays an officer named Jericho, whom the Matronage apparently views as attractive breeding stock, but otherwise disposable. On board the train, a young man dutifully scurries about bringing everybody coffee — a direct mirror universe version of Hawks. Carpenter doesn’t pull off the gender reversal as well as he does the Martian native uprising, but the Matronage adds more to ponder while watching the film. As world-building concept, it’s not a bad starting point.

Emerging classic? Probably not

Ghosts of Mars deserves more discussion and appreciation, but I cannot foresee it evolving into a re-discovered classic with an active cult following. I understand why people reacted negatively to it in the first place; with blockbuster filmmaking changing so radically (the first Lord of the Rings and Harry Potter movies were mere months away), Ghosts of Mars must have looked creaky, cheap, and out of touch to contemporary viewers. Time has sanded away some of the problems — the model-based special effects feel almost endearing now — but Ghosts of Mars never achieves the level where it flat-out “works.” Analysis of the movie’s themes cannot compensate for some poor direction, scripting, and acting.

The performances count as the most noticeable failure. Natasha Henstridge flatlines as the drug-addicted rough-edged hero Lt. Ballard. Courtney Love was originally cast in the part, which makes sense, but she dropped out a week before production started and Henstridge came in at the last minute. I admire her commitment in a tough situation, but Henstridge is a former fashion model who acts exactly like a former fashion model. Ice Cube doesn’t fare much better as the good/bad man, and he and Henstridge develop no chemistry either as antagonists or allies. Carpenter worked magic before with characters given no backstory whatsoever (The Thing), but here the “subtle” characterizations don’t work at all, leaving us with a gaping hole in the center of the movie. When Henstridge delivers the key line — the “dominion” declaration — it’s almost impossible to believe her character means it or has that kind of passion. Maybe that’s a reason nobody in 2001 seems to have noticed how overtly regressive the film’s concept is.

In the narrow acting plus column are the Martian berserkers, played with fantastic primal savagery by what I presume are stunt performers. There’s a bit of fun with Jason Statham as the male version of female eye-candy; he gets a bit more reaction from Henstridge than Ice Cube does. Also delivering an understated performance is Clea DuVall as Bashira, “the rookie,” also cast the opposite gender of her Western counterpart. She seems to promise that the character will turn into something more than we see at first, but the script never delivers.

In the narrow acting plus column are the Martian berserkers, played with fantastic primal savagery by what I presume are stunt performers. There’s a bit of fun with Jason Statham as the male version of female eye-candy; he gets a bit more reaction from Henstridge than Ice Cube does. Also delivering an understated performance is Clea DuVall as Bashira, “the rookie,” also cast the opposite gender of her Western counterpart. She seems to promise that the character will turn into something more than we see at first, but the script never delivers.

Aside from these few flashes in the cast, you won’t enjoy much of the time spent with the characters, and that’s a damning criticism to write about a film from the man who made The Thing, Big Trouble in Little China, and Escape from New York, all of which are chockablock full of memorable figures.

I’ve so far left unmentioned the most criticized aspect of the film: the unusual structure. Lt. Ballard narrates the story to an investigation board after the Yankee pulls into Chryse station with only her aboard. Nothing unusual here, a standard film noir trope. But the flashbacks start becoming imbedded like Russian nesting dolls, with characters having flashbacks within flashbacks within the flashback. At one point, Ballard explains how Jericho told her how a mine survivor told him about the first time the microorganisms attacked. To add to the sense of overlapping memories, Carpenter uses photographic tricks like crossfading within the same shot and numerous odd wipes and reveals. Like much of Ghosts of Mars, it’s more interesting than effective. Or: “I get what you’re doing, but I don’t like it.” If Carpenter tried some of these ideas in the 1980s when he still seemed to enjoy what he did for a living, it would have worked.

The same “nice in theory” problem applies to the Matronage. Thinking about the Matronage’s effect on the story is more enjoyable as an after-movie exercise than anything the Matronage actually does on screen. Williams makes a crack about “running from the Woman,” and there are some tidbits of sexual politics (the majority of the members of the Matronage are lesbians, and “breeders” like Ballard and Bashira have trouble rising up the vocational ladder), but otherwise the matriarchal background never gels as a commentary or an effective inversion of Howard Hawks.

I think the keyword for the trouble with Ghosts of Mars is “malaise.” Carpenter retired from Hollywood after the movie flopped, claiming he felt burnt out, and you can feel that energy sinkhole everywhere in the film. Buried inside Ghosts of Mars exists a fantastic 1980s John Carpenter science-fiction version of Assault on Precinct 13 combined with a controversial take on old Westerns. That hypothetical film is a classic; it’s one of fandom’s most beloved objects, and its gender politics and attitude toward Hollywood racial stereotypes remain points of heated discussion. Unfortunately, that film does not exist: we only have fragments. There was something here, but Carpenter no longer felt the love to make it happen.

But did ya’ have a good time?

Uhm, in places I did. Most of the enjoyment in Ghosts of Mars comes from interacting with it in ways beyond the surface science-fiction/action level. I enjoy thinking about Ghosts of Mars, but I’m not prepared to run back and view it again for leisure any time in the near future. In Carpenter’s canon, I’d slot it above Village of the Damned, The Ward, and Memoirs of an Invisible Man, but I cannot imagine it rising farther no matter how many years pass.

Uhm, in places I did. Most of the enjoyment in Ghosts of Mars comes from interacting with it in ways beyond the surface science-fiction/action level. I enjoy thinking about Ghosts of Mars, but I’m not prepared to run back and view it again for leisure any time in the near future. In Carpenter’s canon, I’d slot it above Village of the Damned, The Ward, and Memoirs of an Invisible Man, but I cannot imagine it rising farther no matter how many years pass.

Taken as a basic SF action picture, the movie fails to deliver: none of the set-pieces are memorable or well-staged, and the characters leave few impressions or even juicy lines (“dominion” excepted). During the finale, at least one character simply vanishes, not so much killed as forgotten, and I didn’t even realize it until the credits rolled.

But that I’m still pondering Ghosts of Mars and discovered so much to write regarding it should stand as statement enough that the film is superior to its rancid reputation. I scanned over some of the disposable summer flicks from 2013 and 2012, and have only fleeting memories of many of them. (I have evidence that I watched the re-make of Total Recall, but… someone erased my actual memory.) However, Ghosts of Mars will stay as sharp as the jagged rocks of Mars in my mind. So John Carpenter wins.

The Ghosts of Mars Blu-ray is an older release from Universal Home Video, and like most of their catalogue titles, has nothing particular to recommend it beyond, “Yeah, the film’s in focus.” The disc has a commentary featuring Carpenter and Henstridge that was recorded in early August 2001 for the DVD release. I got five minutes into it before I realized it was going to be one of those commentaries: Carpenter, after complaining about how unrealistic the model train looks, says: “So, Natasha, you started out your career as a fashion model. Tell us about that.” Then I realized, Oh no, John doesn’t want to talk about the movie. No question, Carpenter was burned out even before the film premiered.

But if anybody deserves a rest to play video games and watch the Lakers, it’s John Carpenter.

Ryan Harvey is a veteran blogger for Black Gate and an award-winning science-fiction and fantasy author who knows Godzilla personally. He received the Writers of the Future Award for his short story “An Acolyte of Black Spires,” and his stories “The Sorrowless Thief” and “Stand at Dubun-Geb” appeared in Black Gate online fiction. All these tales take place in his science fantasy world of Ahn-Tarqa. A further Ahn-Tarqa adventure, “Farewell to Tyrn”, the prologue to the upcoming novel Turn Over the Moon, is currently available as an e-book. You can keep up with him at his website, www.RyanHarveyWriter.com, and follow him on Twitter.

Ryan,

Great article. I can’t believe I never noticed the obvious western allusions.

No, I was too busy paying attention to the one aspect of the film that I thought really worked: the possession angle. While never truly as effective as the paranoia of THE THING, it certainly brought back powerful echoes of that film, as you constantly found yourself wondering who would succumb next. And the sinister alienness of the newly possessed, and the strange bone relics they made, really ratcheted up the tension.

Unfortunately, where the possessed were genuinely frightening one-on-one, by the end of the movie their creepiness was substantially diluted. The en masse street battle wasn’t much more frightening than the battles in ROAD WARRIOR (and that’s sort of what the possessed looked like). A major let down.

Very interesting stuff. Like you say — rewind 15 years and Carpenter would have made a classic.

I’ve tried to love this movie. Tried really hard; the Platonic ideal of this movie is probably the favorite film of an alternate universe me. ‘Malaise’ sums this up really well.

Also, how about the babbling of the lead baddie (pictured above)? I got an aunt who is a heavy smoker, she sounds just like that when she’s cooing over a baby. YOu’d think someone would have suggested a different approach to the guy.

But, as you say, better than most of the drek they put out now.

Bill, I think the alternate universe where this film is a classic is the universe where The Thing was a smash hit in the summer of ’82, and Universal gave Carpenter carte blanche to do another project for them. So Carpenter said, “Hey, I want to do a Mars-set Western version of Assault on Precinct 13.” He cast Kurt Russel as James “Desolation” Williams. Ghosts of Mars came out in 1984, but performed poorly… only then to develop a massive cult following in the 1990s and is now one of Carpenter’s most beloved films.

Interesting review. You can analyze a mess and try to resurrect something out of it. But, at the end of the day, if it really is a mess, I think you’re just left with a mess.

That said, I still like this movie. My defense is that it’s one of those low-expectations-but-ending-up-surprised sort of thing. I thought it was genuinely creepy towards the beginning, though it majorly lost its steam toward the end.

Now that you’ve done three so-so or not so great movies of Carpenter’s, now you HAVE TO review the good ones!

Something else that frustrates me about this movie is the casting feels askew. I can’t help thinking that if you reversed Statham and Ice Cube’s casting, with Statham as Williams, and then cast Pam Grier as Ballard instead of killing her off after giving her barely anything to do, you might have some more watchable actors as the main protagonists. It wouldn’t fix a lot of the other problems, but I’d like it a bit more.

I think the movie is…okay. It’s clearly a few rungs beneath Carpenter’s best movies, but the reviews and audience reactions in 2001 were BRUTAL. Critics in particular have never liked Carpenter much, even despite the rising status of many of his films (I remember a review in the late-1990s that mocked The Thing as if it was still 1982), and I think they took the film as an excuse to carve him with some freshly sharpened knives.

Andy, I like Phil Noble Jr’s observation on the critics savaging the film in 2001: “Although the film can’t help but look low-rent next to the films which opened alongside it, today it feels as if Carpenter got a raw deal for simply making another John Carpenter movie.”

On the one hand, I remember being deeply dissatisfied with this film when it came out. Before I saw Ghosts of Mars, I routinely claimed I would buy a ticket for any movie in which the women had weapons. After Ghosts of Mars, I got a lot pickier, because my old rubric had failed me so badly.

On the other hand, I remember being dissatisfied with the film, though I’ve forgotten ever seeing a lot of the films I went to around the same time. I remember thinking the Martians’ aesthetic sensibility was fascinating, and marveling that Carpenter could get me to see the beauty the Martians saw in their ghoulish creations. I remember thinking the matriarchal social structure could have been interesting, but feeling that the film came off as vaguely misogynistic and homophobic. Though I had no investment whatsoever in John Carpenter–had in fact forgotten that he was the guy who had made the glorious Big Trouble in Little China–I did have a sense of the lost opportunities.

Ah, well, give it a generation or two, and eventually someone will reboot it brilliantly. I like to imagine it will be some kid who got his or her start in Joss Whedon’s tutelage.

[…] it make more sense to have someone polish the many flaws of Ghosts of Mars and give all those interesting ideas the awesome movie they […]

[…] Some have pointed out the battle between the Mars Police Force and the ancient Martians is an allegory to settlers of the American West and their despicable treatment of Native Americans. […]

A great article. I happen to disagree with some parts.

But we’re adult I can enjoy your article without agreeing with it all.

From a young age I enjoyed John Carpenter films I’d seen.

As sat on precinct 13, Halloween, Starman, The Fog Prince of darkness and they live.

I even went to the cinema to watch Memoirs of an Invisible Man, although only directed by Carpenter due to the original director being dismissed due to Chevy Chase disliking him.

It took me nearly thirty years to watch every film he directed.

When Ghosts of Mars came out on Video I rented it from my local video shop.

I remember being very disappointed.

However like some of his other films I gave it a few more watches over the years and it grew on me like a flesh eating virus.

I heard Jason Statham was originally bought in to play Desolation Williams?

Ice Cube can play a tough thug as well as anyone. But this one I think Statham would of been a better choice because as we learned in his later films he can play a cheeky thug with a heart of gold.

As for Hestridge I think this was her best role. In Species and it’s sequel it was one dimensional and was there mainly for sex appeal.

Yes some scenes she falls flat but overall being brought in at short notice with no rehearsal or time to build a repour with the other cast I think she did great.

Normally in film you build chemistry with the cast while rehearsing.

I’m sure there’s a few films where a last minute actor has done better. I personally remember one especially that was Michael Biehn in Aliens as Corporal Hicks. But Biehn is a trained actor and Hestridge is a trained model.

Is Ghosts of Mars his Best film… No.

But it definitely not his worse. Definitely didn’t deserve the stick it got and basically sidelined one of the best Directors ever.

Granted I know he directed 2 episodes of Masters of horror TV series, Cigarette Burns being one of the best stories, and the Ward has all intense and purposes has caused him to retire.

That’s a damn shame when you think about the rubbish being collected and then thrown at the wall Hollywood currently dishing out.