The End of Time and Me: Michael Moorcock’s Dancers at the End of Time

|

|

|

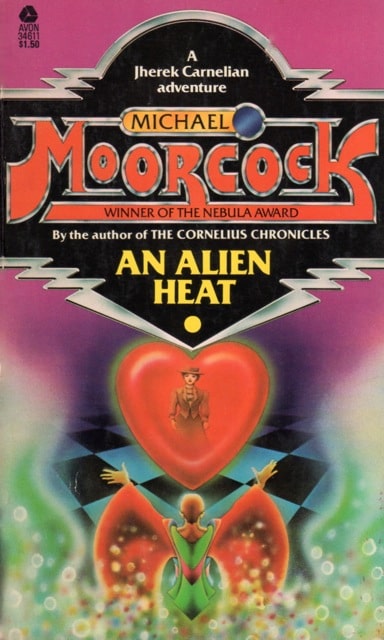

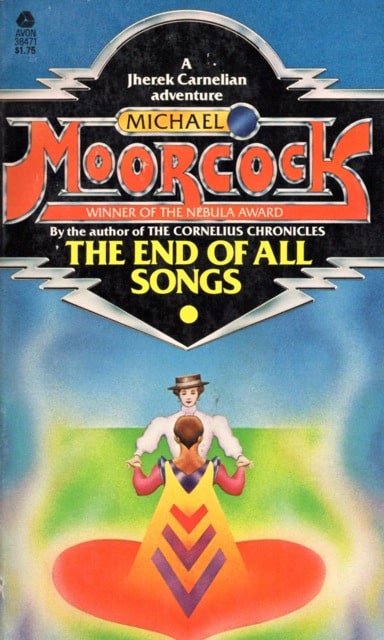

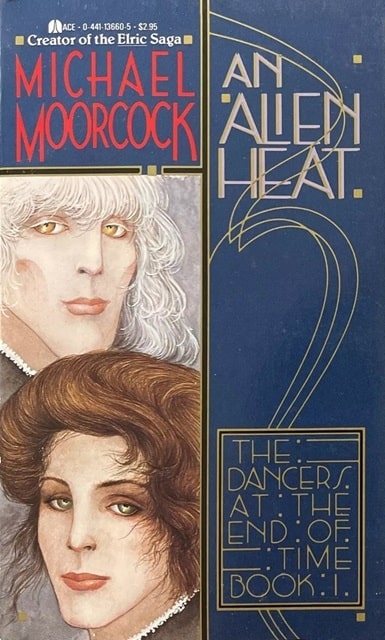

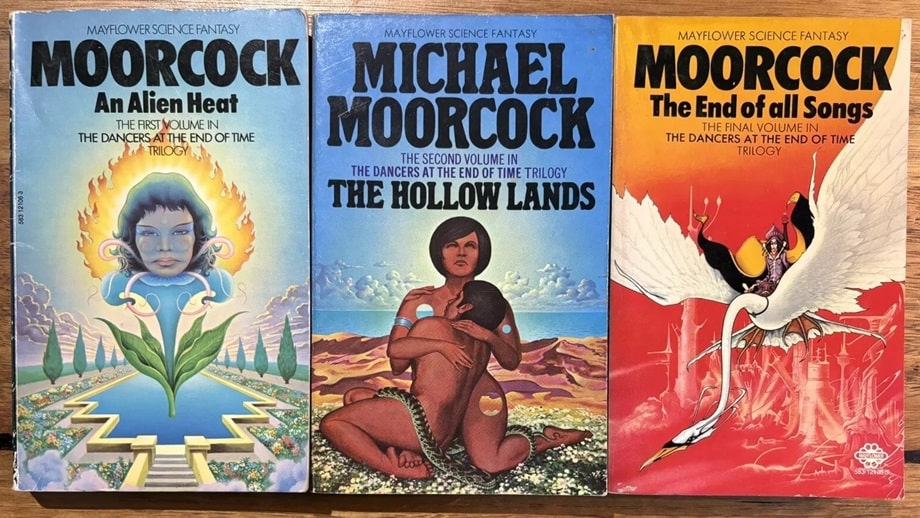

The Dancers at the End of Time trilogy: An Alien Heat, The Hollow Lands,

and The End of All Songs (Avon Books, September and November 1977,

and June 1978). Cover art by Stanislaw Fernandes

When I discovered Moorcock in the early 1980s, I read his trilogy Dancers at the End of Time and the associated novel A Messiah at the End of Time. I remember enjoying the trilogy, though I have only vague memories of the stand-alone novel. Back in 2017, I re-read Moorcock’s Elric series and wrote about it for Black Gate. In 2020, I did the same for his Corum novels and in 2022, I revisited Erekose. Rather than look at Hawkmoon, which I last re-read in 2010, I decided to dive into The End of Time sequence.

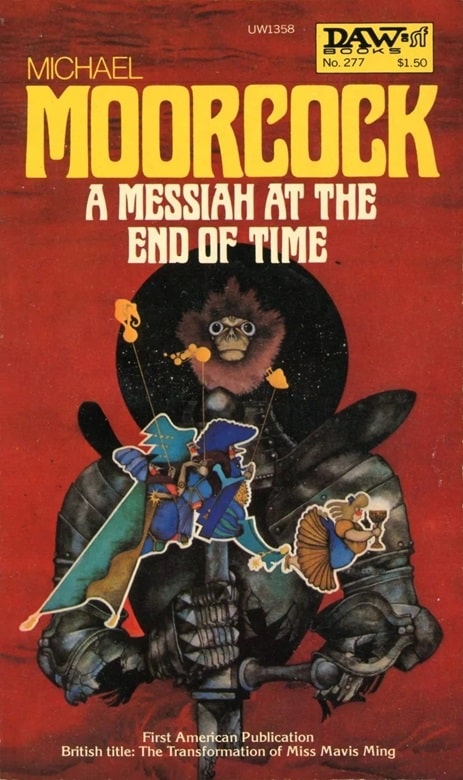

In addition to The Dancers at the End of Time trilogy and the novel The Transformation of Miss Mavis Ming (also published as Messiah at the End of Time and Constant Fire), Moorcock has written several short stories that belong to the sequence: “Pale Roses,” “White Stars,” “Ancient Shadows,” “Elric at the End of Time,” and “Sumptuous Dress: A Question of Size at the End of Time.” Although most were published before I read the trilogy, I believe I missed all of them with the exception of “Elric at the End of Time.”

[Click the images to spend time with larger versions.]

|

|

|

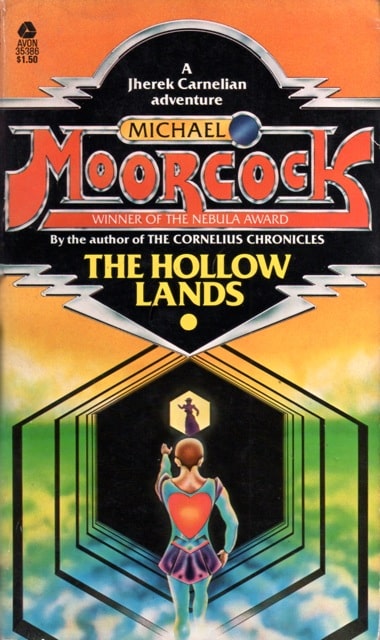

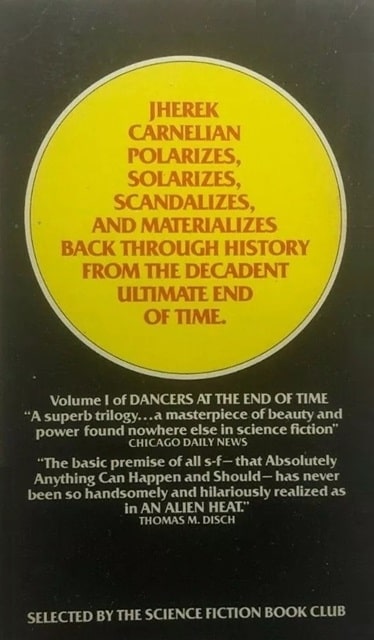

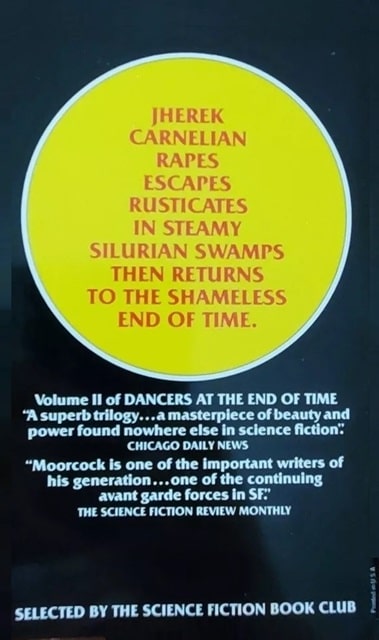

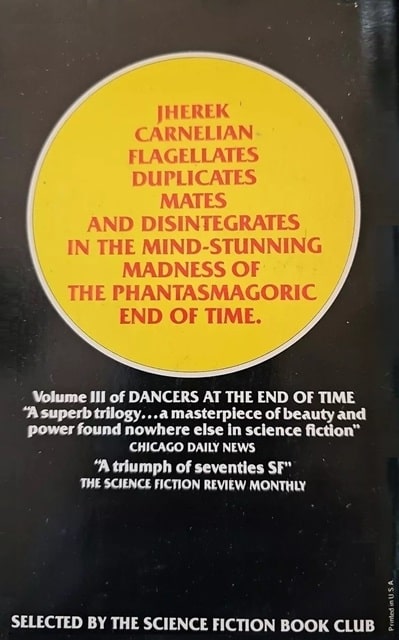

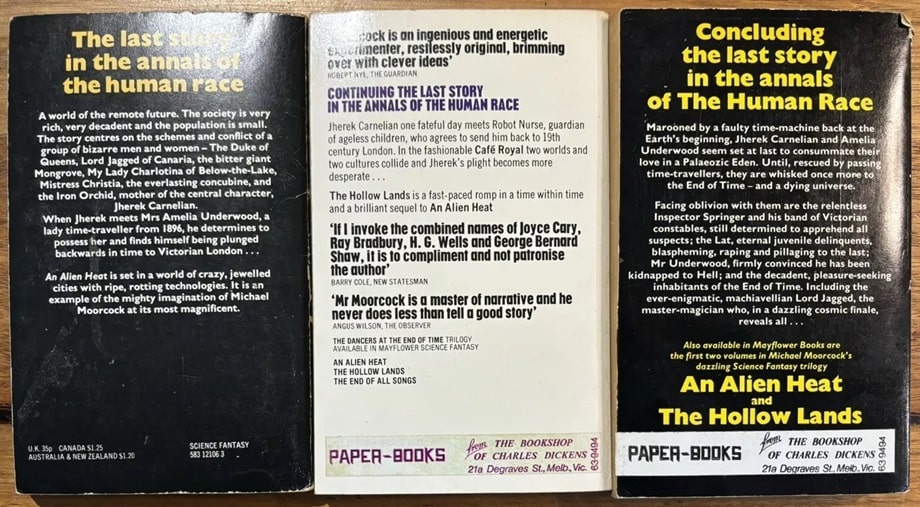

Back covers for An Alien Heat, The Hollow Lands, and The End of All Songs

Moorcock has clearly tied this series into his Elric novels with “Elric at the End of Time,” to his Second Ether series with “Sumptuous Dress: A Question of Size at the End of Time,” and the main sequence ties into The Nomads of the Time Stream (through the appearance of Oswald Bastable), to Jerry Cornelius (through Una Persson), and to Behold the Man and Breakfast in the Ruins with a reference to Glogauer, and The Winds of Limbo when Emmanuel Bloom appears.

Moorcock isn’t the only one to write stories in this setting. In 1996, Caitlin R. Kiernan contributed the short story “Giants in the Earth,” about young Jherek Carnelian, to Michael Moorcock’s Pawns of Chaos: Tales of the Eternal Champion, and in 2011, Steve Aylett published Rebel at the End of Time, about a 21st century revolutionary who finds himself at the End of Time.

The original trilogy, The Dancers at the End of Time, was published between October 1972 and July 1976. It tells a single story that is essentially serialized over the course of the novels, and neither of the first two have a satisfying ending.

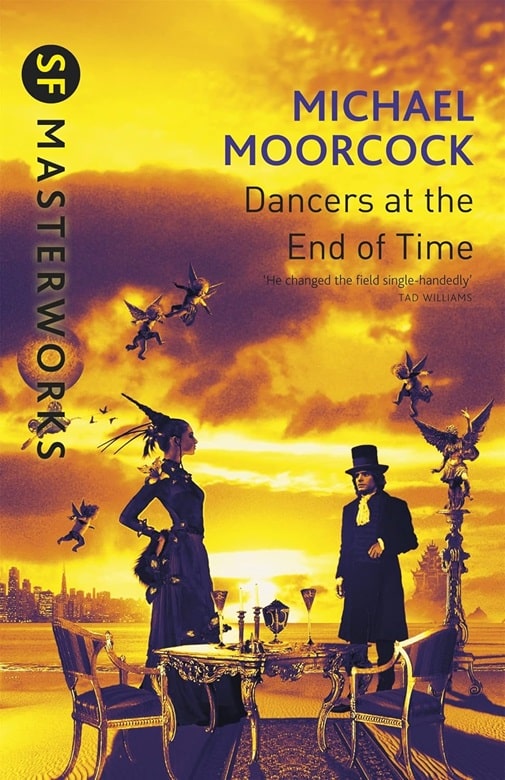

|

|

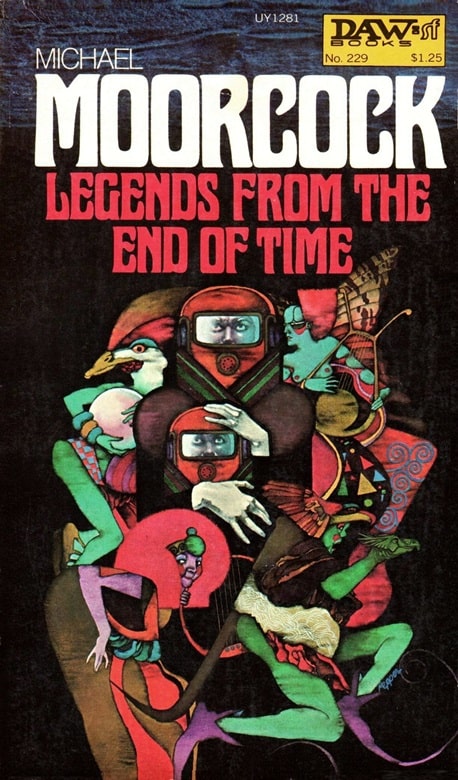

The collection Legends From the End of Time, containing “Pales Roses,” “White Stars,”

and “Ancient Shadows” (DAW Books, February 1977). Cover by Bob Pepper

When I reread the series I discovered more of it took place in Victorian England than I remembered, along with a brief sojourn to the beginning of time. While aspects of the main characters – Jherek Carnelian, Amelia Underwood, Lord Jagged, and Iron Orchid – remained with me, most of the other characters, whether natives of the end of time, Victorians, or aliens, hadn’t made a lasting impression. In fact, over the decades since I first read the novels, I had completely forgotten that the alien Lat existed.

The most interesting character in the series is Lord Jagged, for the very reason that he is the most enigmatic. Introduced as a mentor to Jherek Carnelian, his disappearances throughout the novel (and the simultaneously occurring short stories) is remarked upon by the other characters. When he does show up, it’s often in different guises, either as Lord Jagger, a Victorian judge who presides over Jherek’s murder trial in An Alien Heat, or as Mr. Jackson, a reporter in The Hollow Lands. Moorcock slowly reveals his story throughout the three novels.

While the original trilogy focuses on the mechanizations of Lord Jagged of Canaria and the romance of Jherek Carnelian and Mrs. Amelia Underwood, all of the stories use the trilogy’s supporting cast, as well as the general decadent nature of the End of Time and copious time travel. By focusing on these minor characters, and taking a slightly different tack with each story, Moorcock more fully explores the world.

|

|

|

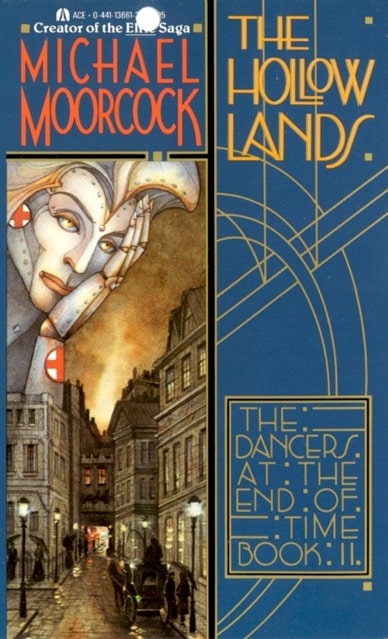

Ace paperback editions of An Alien Heat, The Hollow Lands, and The End

of All Songs (July and November 1987, February 1988). Covers by Robert Gould

In “Elric at the End of Time,” Elric sees the denizens of the End of Time as the Lords of Chaos, with Lord Jagged playing the role of (and potentially being) Arioch. That interpretation of the period continues in many of the stories, and in “White Stars” – in which the Duke of Queens decides he must duel with Lord Shark – the concept of the world being ruled by Chaos is reinforced.

The series is not for everyone, and it explores a fair number of taboo subjects in a non-judgmental way. An Alien Heat opens with The Iron Orchid and her son, Jherek Carnelian, having sex. Similarly, the story “Pale Roses” features Werther de Goethe having sex with his underage ward, Catherine Gratitude, although Moorcock uses that instance to explore Werther’s sense of guilt for betraying the responsibility he felt for her. Unfortunately, Moorcock undermined Werther’s sense of guilt and, as happens in most of these stories, there’s no sense that anything will have an ongoing impact.

Mavis Ming first appears in the short story “Ancient Shadows” as a bit of a sexual predator, but by The Transformation of Mavis Ming the tables have turned and she finds herself the object of unwanted sexual attention.

|

|

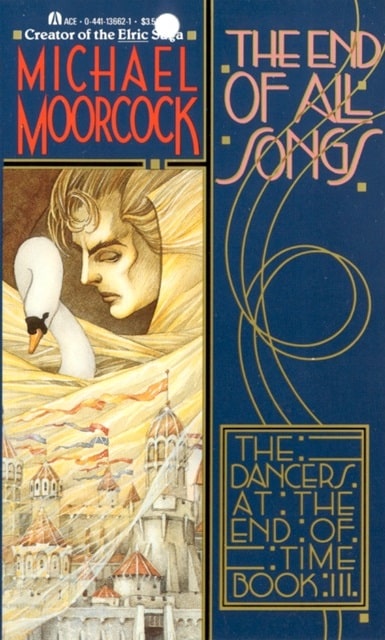

A Messiah at the End of Time (DAW, February 1978), published in

the UK as The Transformation of Mavis Ming. Cover by Bob Pepper

One of the interesting things about the novel is that it’s been published under three different titles, seeing a reprint as A Messiah at the End of Time — which changes the reader’s focus from Mavis Ming to her antagonist, Emmanuel Bloom – and subsequently with the more neutral title Constant Fire. Unfortunately, none of the characters in Constant Fire are particularly sympathetic. Ming is a vapid, unpopular woman who has no clue how she impacts others; her patron, Lord Volospion is manipulative, and Bloom is an egomaniacal sexual predator.

Re-reading the series, and reading the stories for the first time, I find that I don’t have as much of a connection to them as I once did. The short stories actually worked better for me. In the novels, it feels as if nothing really matters. No matter how ardently Jherek proclaims his love for Amelia, or the lengths he goes to pursue her, he always seems to be playing a role. He has romanticized romance without understanding what it is, only to learn, slowly, through Amelia’s attempts to teach him when he doesn’t fully comprehend the basics. The other characters are merely following what they see as the latest trends.

Ironically, in the short stories, Moorcock explores issues more fully. The main characters are allowed to change and be more complex. Whether it’s Werther de Goethe’s understanding responsibilities and obligations, or the Duke of Queens actually having to learn a skill rather than just make something happen, the characters exhibit the need and ability to change, even if, in the end, these changes turn out to be as fleeting as anything in the main sequence.

Mayflower (UK) paperback editions: June 1974, 1975, and September 1977. Covers by Bob Haberfield

During my first rereads for this series, the Elric novels stood up the best. The Corum novels surprised me, since the trilogy I remember preferring was no longer my favorite. Erekose also stood up pretty well. I remember enjoying The Dancers at the End of Time, but re-reading it now, a lot of it felt as if there was little point. Throughout the novels, Moorcock makes it clear that there are no consequences for characters’ actions. Death was just a temporary state and goals and emotions were simply whatever was fashionable at the moment.

Jherek Carnelian claims to want to experience love, but love, along with several other concepts Amelia Underwood introduces him to, has no real meaning. Although he maintains his love for her, it is less love for Amelia and more the love of the idea of being in love. Nothing she can say or do can change what he thinks he feels, and the reader is left with the sense that anyone would have been as suitable a target for his advances.

|

|

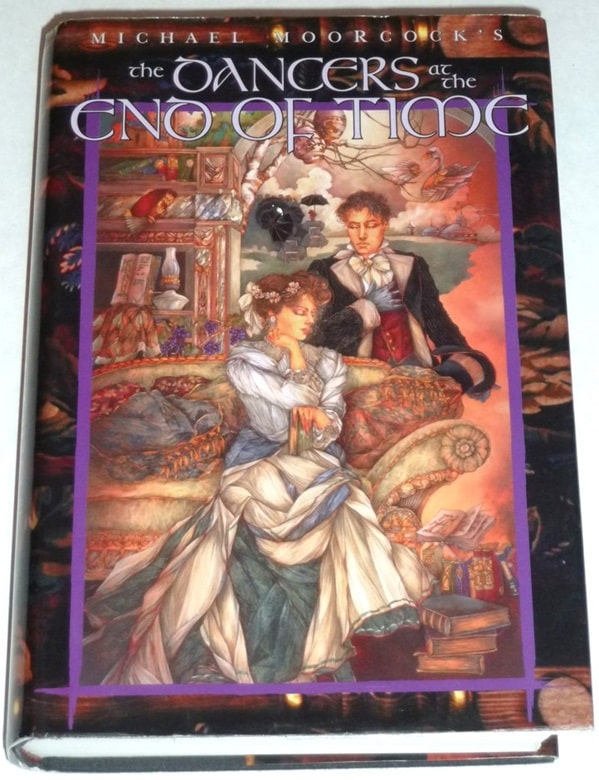

Omnibus editions: White Wolf (May 1998), and Gollancz SF Masterworks

(May 2003). Covers by Tom Canty and Steve Stone

Similarly the stakes for Mavis Ming – while higher since she knows, perhaps not what she wants, but what she doesn’t want – also don’t seem to be real. Just as Jherek lacks any concerns for his target’s feelings, so too does Bloom completely fail to care about the desires of the woman he claims to love (and, perhaps worse, believes he knows what is right for).

I have a feeling that the freedoms and liberty of the various characters, combined with their near omnipotence, appealed more to me as a teenager than they do at my current age. They come across more as cartoon characters than people.

Steven H Silver is a twenty-time Hugo Award nominee and was the publisher of the Hugo-nominated fanzine Argentus as well as the editor and publisher of ISFiC Press for eight years. He has also edited books for DAW, NESFA Press, and ZNB. His most recent anthology is Alternate Peace and his novel After Hastings was published in 2020. Steven has chaired the first Midwest Construction, Windycon three times, and the SFWA Nebula Conference six times. He was programming chair for Chicon 2000 and Vice Chair of Chicon 7.

Steven H Silver is a twenty-time Hugo Award nominee and was the publisher of the Hugo-nominated fanzine Argentus as well as the editor and publisher of ISFiC Press for eight years. He has also edited books for DAW, NESFA Press, and ZNB. His most recent anthology is Alternate Peace and his novel After Hastings was published in 2020. Steven has chaired the first Midwest Construction, Windycon three times, and the SFWA Nebula Conference six times. He was programming chair for Chicon 2000 and Vice Chair of Chicon 7.

I love those Avon covers up at the top.

This is a series that I read when I first got into Moorcock, mostly because they happened to have them at the public library, but at the time I couldn’t quite make head nor tail of them. I haven’t read them for a good few years now (someday; someday), but thinking about it, they strike me as very transitional as Moorcock moves from the more traditional, pulpy fantasies of Elric and Corum to the more self-consciously literary prose stylings of the Von Bek books &c.

These books have always seemed to me to be so much “of their moment” that they were destined not to age well.

I read the original trilogy in the mid-70s on loan from my library (Nichols Library in Naperville, and the real one, not the soulless new building!) I loved it. It is by far my favorite of Moorcock’s works, though I confess I have not reread it, so my evaluation might change! You may be right that as an adult I might react very differently to some of it.

At about the same time, I noticed Anthony Powell’s A Dance to the Music of Time series — attracted to the title by the resemblance to Moorcock’s books. I took a glance and I though, gosh, that looks boring …

I finally read Powell’s novels (there are 12 in the series) some time in the 1990s and they became perhaps my favorite novels of the 20th Century. But I admit, I wouldn’t have appreciated them at 16 or so. I wouldl not be surprised to learn that Moorcock chose his title partly as a reference to Powell’s novels, though I’m pretty sure Moorcock disapproved of Powell, largely on political grounds. (I do think Mike has a blind spot for writers who politics differ from his, like Tolkien.)

Now how could Moorcock find anything to disapprove of in Kenneth Widmerpool?

Only stumbled onto a copy of Legends from the End of Time a few years ago, and I did enjoy reading the stories. With all the re-reading disappointments, I wonder if I should go back to the trilogy and see how my tastes have changed.

And I admit that one of the elements that I do recall from the original trilogy are the Lat, simply due to the silly joke of having them being constantly confused with “Latvians”.

Started reading Moorcock in high school thanks to Appendix N and the library. Read Hawkmoon & Corum in college thanks to the terrific used book stores in Madison. Started Jerry Cornelius and my Moorcock reading ended there. A combination of a protagonist that I couldn’t root for and a setting that wasn’t anything I cared for. I feel that the Carnelian books would be similar. I’ve reread Hawkmoon and some of the Elric books (first three of the six) in the last decade and enjoyed Hawkmoon more than Elric. In part, again, because of the protagonist and possibly because of the “Tristan and Isolde” or “Romeo & Juliet” aspect of Elric and Cymoril. Knew it wouldn’t end well.