Neoclassical Adventure

If you’ve been following the online discussion of tabletop roleplaying games (especially fantasy roleplaying games) over the last few years, odds are good you’ve heard of the “Old School Renaissance.” For that matter, if you’ve been following the RPG coverage here at Black Gate, you’ve probably already noticed this term being used in numerous blog entries before this one. As folks online are wont to do, some will quibble and kvetch about the precise meaning of the OSR (as it’s come to be known; it even has a logo!), but, at its most basic, the Old School Renaissance is a renewed appreciation for the RPGs of the 1970s and ’80s, as well as a renewed interest in playing these classic games.

If you’ve been following the online discussion of tabletop roleplaying games (especially fantasy roleplaying games) over the last few years, odds are good you’ve heard of the “Old School Renaissance.” For that matter, if you’ve been following the RPG coverage here at Black Gate, you’ve probably already noticed this term being used in numerous blog entries before this one. As folks online are wont to do, some will quibble and kvetch about the precise meaning of the OSR (as it’s come to be known; it even has a logo!), but, at its most basic, the Old School Renaissance is a renewed appreciation for the RPGs of the 1970s and ’80s, as well as a renewed interest in playing these classic games.

Gamers being what they are (and always have been), it wasn’t long after the OSR picked up steam that people wanted to start producing new material for their favorite RPGs, a desire facilitated by the Open Gaming License and System Reference Document that Wizards of the Coast released at the same time as the Third Edition of Dungeons & Dragons in 2000. Together, they made it possible to create and sell “clones” (or “retro-clones”) of popular roleplaying games from the past, games that are in many cases are long out of print or locked away in the IP vaults of a corporation. Want to write an adventure for your beloved 1981 edition of D&D? Labyrinth Lord lets you do that. Want to publish a new campaign setting for AD&D? OSRIC gives you the tools for just that. There are also clones for games like RuneQuest, Gamma World, Chill, and many more, not to mention many older games that have come back into print as a result of the renewed interest the OSR has generated in them. Whatever your favorite game of the past, odds are good that you’ll be satisfied.

There’s another category of old school RPGs, however. They’re not clones, since they aren’t modern-day restatements of older rules sets, but they do take clear inspiration from their predecessors of yore. They are, for lack of a better term, neoclassical roleplaying games.

There are almost as many neoclassical RPGs available now as there are clones, maybe more, so it’d be impossible for me to talk about them all here, even if this blog entry were ten times its length. For that reason, I’m going to draw your attention to two that I find especially notable. In both cases, the game in question is a fantasy roleplaying game informed by its author’s love of and experience with other fantasy games, especially the grandfather of them all, Dungeons & Dragons. To my mind, there are two things that make these games worth discussing. The first is the way that each has mined the rich veins of old school game design from which to craft thoroughly original and modern (in the sense of not being mere apes of what has come before) RPGs. The second – and more important from my perspective – is the strong authorial voices that these games possess. When reading them, it is impossible not to feel that it was conceived and written by a real person with very specific likes, dislikes, and quirks rather than a focus group-driven committee. In that respect, these games truly harken back to the earliest days of the hobby, as anyone who’s read the 1974 edition of D&D knows.

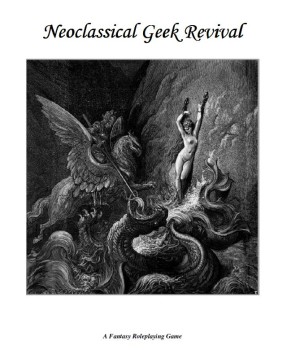

Zzarchov Kowolski‘s evocatively named Neoclassical Geek Revival (or NGR) is the game that inspired this post, as you might well imagine. In the game’s introduction, he describes it thus:

Zzarchov Kowolski‘s evocatively named Neoclassical Geek Revival (or NGR) is the game that inspired this post, as you might well imagine. In the game’s introduction, he describes it thus:

NGR is a fantasy heartbreaker RPG; it does what you would expect out of a traditional fantasy role-playing game. While NGR will work as a complete game, I have no doubt it will rarely be played as such. This game is designed expecting that you will see things in this game you would like to remove and plug into your own game rather than playing it whole-cloth.

This game is designed to simulate low-magic fantasy, but most mechanics are equally at home in a science fiction, action or post-apocalyptic game. The rules are designed to be as setting neutral as possible while solving commonly held gripes and bad tropes. In the writing of this game I used the following as guiding principles:

1.) Funny dice are fun on their own merits

2.) Choices to make are better than problems to solve

3.) You are already familiar with role playing games

4.) You don’t want to trick people into wrong choices with their character

5.) You want both detail and speed with mechanics

6.) You want to cut down on the time it takes to prepare a game

7.) You like player driven games

It was this introduction that made me fall in love with NGR and Kowolski’s distinctive writing style. Unlike many game designers, he neither shies away from speaking directly to the reader nor from using colloquial, even idiosyncratic, language. A good example of this is the game’s use of “pie pieces.” Pie pieces represent a portion of a class’s unique powers, such as a warrior’s ability to dual wield or a wizard’s psychic potential. Players may choose to acquire pie pieces in a single class for their characters (in which case they’re more potent but specialized) or they may choose to acquire pieces from several classes (in which case they’re more mediocre but broadly skilled). While not groundbreaking in its design, its presentation is accessible and inviting. The same is true of its sections on combat and other conflicts, spells, miracles, and adventuring.

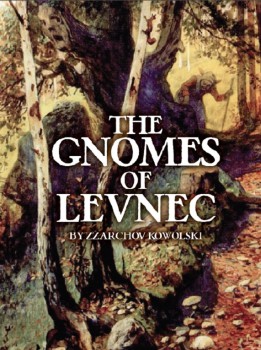

Where NGR really shines, though, is  in its supporting adventures, two of which are currently available. The first, The Gnomes of Levnec, is intended for beginning characters and presents a sleepy little village (called Levnec) in the midst of a great wood in which strange things are happening, none stranger than the gnomes who live nearby. The second, A Thousand Dead Babies, is also a beginning adventure set in a small town. In this case, the central conflict concerns religious turmoil between followers of the Holy Church and those who cling to the worship of the Old Gods. In both cases, the adventures are more situations than than scenarios in the traditional sense. That is, they provide several locations, flesh out the various folk who dwell there, and map out a conflict or conflicts into which the unsuspecting characters might stumble. There are no plots or story arcs or anything resembling a grand plan – just a bunch of building blocks teetering precariously on top of one another. As much as I love Neoclassical Geek Revival, I think the adventures are even more lovable (and are written in a way that suggests Kowolski could teach a thing or two to many “professional” adventure writers of greater fame).

in its supporting adventures, two of which are currently available. The first, The Gnomes of Levnec, is intended for beginning characters and presents a sleepy little village (called Levnec) in the midst of a great wood in which strange things are happening, none stranger than the gnomes who live nearby. The second, A Thousand Dead Babies, is also a beginning adventure set in a small town. In this case, the central conflict concerns religious turmoil between followers of the Holy Church and those who cling to the worship of the Old Gods. In both cases, the adventures are more situations than than scenarios in the traditional sense. That is, they provide several locations, flesh out the various folk who dwell there, and map out a conflict or conflicts into which the unsuspecting characters might stumble. There are no plots or story arcs or anything resembling a grand plan – just a bunch of building blocks teetering precariously on top of one another. As much as I love Neoclassical Geek Revival, I think the adventures are even more lovable (and are written in a way that suggests Kowolski could teach a thing or two to many “professional” adventure writers of greater fame).

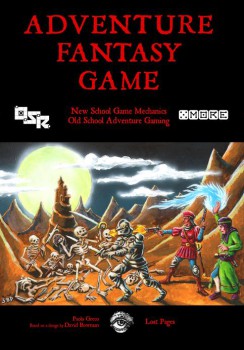

Paolo Greco‘s Adventure Fantasy Game (or AFG) is about the same length as NGR and, like it, helpfully describes itself in its own introduction:

This is another fantasy adventure game. Does the world need another one? Of course!

AFG exists to run fantasy sandboxes where players are free to get involved with exploration, traveling, politics, dungeoneering, city-life and trading as much as they want. The aims of the rules are the following:

- Use only six-sided dice: grab a die and roll high.

- Rules and equipment should be suited to pick up play: simple enough to be taught and grasped in minutes, using only six-sided dice.

- Quick and easy character creation, that does not require players to browse and pick options from a long list.

- Straight compatible with other games’ materials, involving in the worst case small adaptations.

- Minimum beancounting and fiddling. No experience points to track or interminable lists of character options. Modifi ers, both in numbers and amounts, are small.

- Interesting choices must lead to important consequences.

- Rules must have a purpose and guide the narrative. Rewards must provide a clear direction for players: desired in-game actions must be rewarded by in-game rewards.

As you can see, the re’s a certain similarity in approach between the two games, as well as a similarly strong voice. Greco’s prose is not as colloquial as Kowolski’s, but it’s still easy to follow and understand. More importantly, he conveys his enthusiasm, humor, and creativity through numerous examples and asides, such as a footnote reading, “‘Unless the Referee feels otherwise'” should be applied to everything during the game.” AFG is, to my mind, a bit simpler rules-wise than NGR but not by much. For that reason, AFG has space enough in its page count to devote to an adventure and mini-setting.

re’s a certain similarity in approach between the two games, as well as a similarly strong voice. Greco’s prose is not as colloquial as Kowolski’s, but it’s still easy to follow and understand. More importantly, he conveys his enthusiasm, humor, and creativity through numerous examples and asides, such as a footnote reading, “‘Unless the Referee feels otherwise'” should be applied to everything during the game.” AFG is, to my mind, a bit simpler rules-wise than NGR but not by much. For that reason, AFG has space enough in its page count to devote to an adventure and mini-setting.

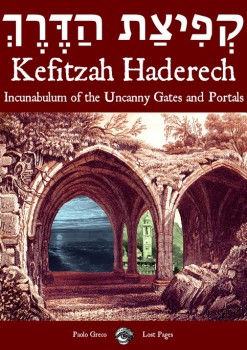

Like Neoclassical Geek Revival, Adventure Fantasy Game is supported by several additional products, in this case supplements. The first is Kefitzah Haderech, which focuses on portals and dimensional gates, while the second, Pergamino Barocco, is devoted to spells. Both supplements are gorgeous, looking very much like early printed books. This is particularly effective in the case of Pergamino Barocco, where reading it almost feels as if one were perusing an actual spell book. Currently in the works is a campaign setting presented in multiple books, called Chthonic Codex , the first parts of which will start appearing later this year. There are even plans to produce a boxed version of the material, which warms my middle-aged heart, remembering wit fondness as I do the many boxed RPG sets from my youth decades ago.

Both games show that good RPG design is about more than reinventing the wheel. It’s about providing players and referees alike with straightforward, intelligible rules, coupled with imaginative uses for those rules. Just as important, I think, is material written by designers who strongly convey that they enjoy playing their own games. That joy is infectious and is probably the best way to convince someone to pick up a new roleplaying game and play it. That was the case back in the late ’70s, when I first rolled some dice around a table with my friends and it’s no less true today. Games like Neoclassical Geek Revival and Adventure Fantasy Game continue in that fine tradition. They’re clearly labors of love by their designers, evincing the fun they feel for this weird hobby of ours. I cannot recommend them highly enough.

One can get rather cynical about OSR and see it simply as a marketing ploy to get money out of us old school gamers.

“Hey, they could barely cobble $8 together for the newest AD&D module back in 1982 when they were in junior high. But these guys have jobs and buying power now. Let’s fleece them with nostalgia!”

And funny thing is, even if this is completely true, I DO fork over money for this stuff. As I type this, right next to my desk is the newest issued of Gygax magazine (which I got over a month ago and still haven’t read), several recently bought, but older, paperbacks connected with older RPGs, and I even have several newer versions of older games (which I still have not played are in much nicer condition than my older junior high RPG books and boxes ever looked).

Nostalgia. It can get expensive.

I need to get the latest issue of Gygax magazine. Really liked the first one.

James,

1) Much, if not most, OSR material is free

And

2) Attraction to older games (or older things or styles, in general) doesn’t necessarily stem from nostalgia. To say it is nostalgia is to falsely assume newer is better – a modern conceit promoted by marketers.

@Tyr

1. I was using “OSR” more broadly to include anything that appealed to gamers who grew up in the 70s or 80s. For instance, I consider all of the WotC re-prints to be an “old school renaissance” of sorts.

2. I agree that attraction to older games does not necessarily stem from nostalgia. But nostalgia need not assume newer is better. I’m greatly nostalgic (of early 80s especially), nevertheless I own many new games and books.

[…] of really good ones being produced these days. A good example of what I’m talking about is Zzarchov Kowolski‘s Scenic Dunnsmouth, published by Lamentations of the Flame Princess in […]