Vintage Treasures: Greg Stafford’s Pendragon

Back in August, I wrote a mini-history of one of my favorite gaming companies, Chaosium, in the middle of a review of Pavis: Gateway to Adventure.

Back in August, I wrote a mini-history of one of my favorite gaming companies, Chaosium, in the middle of a review of Pavis: Gateway to Adventure.

That was fun. Plus, it was a great excuse to wax nostalgic about the brief period between 1981 and 1986, when Chaosium released some of the finest RPGs and RPG supplements ever created. Published in handsome boxed editions, they started with Thieves’ World and continued with Stormbringer in 1981, Borderlands (1982), Worlds of Wonder (1982), Superworld (1983), Pavis (1983), Masks of Nyarlathotep (1984), Cthulhu by Gaslight (1986), H.P. Lovecraft’s Dreamlands (1986), Spawn of Azathoth (1986), Arkham Horror (1984), Ringworld (1984), Elfquest (1984), Hawkmoon (1986), and the fabulous Horror on the Orient Express.

Wonderful stuff. Masks of Nyarlathotep is frequently cited — even today — as one of the finest adventures released for any game system, and Arkham Horror is considered a classic board game, still in print today in a new edition from Fantasy Flight Games. Many titles were expanded and reprinted in later editions, including Stormbringer, Cthulhu by Gaslight, and Dreamlands.

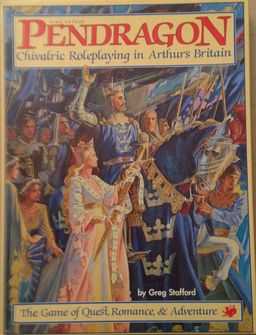

But perhaps the most celebrated release, of a fabulous line up, was the title that legendary game designer Greg Stafford — founder of Chaosium and creator of the fantasy world Glorantha — considered his masterpiece: the Arthurian role-playing game Pendragon.

What’s so special about Pendragon?

Lots of things. But I think to really understand it, you need to remember that Dungeons and Dragons ruled the RPG world in 1981 (as it largely still does today), and that D&D was designed for a very specific type of play.

As James Maliszewski has been exploring in his ongoing series on Appendix N — as well as Mordicai Knode and Tim Callahan, who are examining one Appendix N writer per week in their Advanced Readings in D&D series at Tor.com — that style of play was very much influenced by classic heroic fantasy and Jack Vance and encouraged the kind of fellowship-quest, loot-driven adventuring we know and love today.

As William King noted last month in his review of Crypts and Things, as popular and flexible as D&D was, it wasn’t ideally suited for him:

I wanted to play a game that caught the atmosphere of Robert E Howard’s Conan, Karl Edward Wagner’s Kane, or Fritz Leiber’s Fafhrd and Grey Mouser stories. I wanted to adventure in a place of unholy shadows, where magic was scary and thrilling and men with swords sought lost treasures in glittering towers where old gods and dark secrets waited.

Clearly, D&D was not quite what I was looking for. The white box contained an unholy mishmash of Tolkien, bits of medieval history, and a weird variation of Vancian magic from the Dying Earth which, while awesomely powerful, was not very scary or, well, magical. Magic items were as common as if they came in cereal boxes. And what was with it with those cleric guys and the undead?

Fans of sword & sorcery weren’t the only ones to find D&D (and by extension, fantasy role playing in general) lacking.

For many, the finest form of fantasy didn’t concern itself with looting crypts, fighting orcs, or seeking magic rings. Fantasy was about noble quests, righting wrongs, courtly romance, and the exalted values of the chivalric tradition.

For the millions of fans of Arthurian fantasy — the kind found in Walt Disney’s The Sword and the Stone, Mary Stewart’s beloved Arthurian Saga, T.H. White’s The Once and Future King, Marion Zimmer Bradley’s The Mists of Avalon, Malory’s Le Morte d’Arthur, and countless others — role playing utterly failed to capture anything like what they considered real fantasy.

At least until Pendragon arrived.

Pendragon was subtitled Chivalric Roleplaying in Arthur’s Britain and it scorned the entire premise of killing monsters to gain loot and experience points. Instead, it promised adventures in pursuit of more noble goals in the golden age of knights and ladies.

The ultimate rewards weren’t achieved through gaining levels and winning magical weapons. Instead, players were tantalized with the possibility of joining the Knights of the Round Table and sitting beside Arthur and his famous knights.

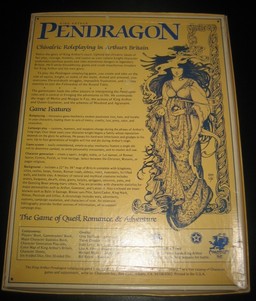

Here’s the back cover text:

Relive the glory of King Arthur’s court. Uphold the chivalric ideals of fair play, courage, honesty, and justice as your caliant knight-character undertakes perilous quests and risks monstrous dangers in legendary Britain. He’ll smite bloodthirsty giants and crush treacherous invaders for King Arthur and his own glory.

To play the Pendragon roleplaying game, you create and take on the role of squire, knight, or noble of the realm. Armed and armored, you overcome life and death struggles, impossible frustration, and ruthless enemies to join the Fellowship of the Round Table.

The gamemaster leads the other players in interpreting the Pendragon rules and is central in bringing the adventures to life. He commands the magic of Merlin and Morgan le Fay, the actions of King Arthur and Queen Guenever, and the schemes of Mordred and Agravaine.

Yeah, it was a little sexist. Okay, very sexist. If you wanted to play a lady in the court of King Arthur — or a female adventurer of any kind — you were out of luck. There was no mechanism to generate female characters in the rules, period.

The book even listed dozens of suggested Pictish, Saxon, Cymric, Malorian and Roman British male names. No female names, of course (why would you ever want those?)

Still, Pendragon had lots of interesting ideas. The game mechanics included ways to trigger powerful passions — love, hate, and loyalty — in your player character, which could in turn produce feats of valor, acts of mercy or cowardice, cruelty, and much more.

Stats — and histories — were provided for most of the major players of the period, including King Arthur, Lancelot, and Guinevere, as well as many minor nobles and villains. A handy chronology is also included, covering major wars and conflicts, quests and adventures, as well as courtly customs, and more.

There’s even a version of Appendix N, in the form of an extensive bibliography, suggesting additional sources of information.

The differences from D&D were obvious. Your character-knight didn’t just gather henchmen and followers — he could beget a whole family, whose reputation in society would wax and wane depending on his accomplishments, legacy, and inheritance — not to mention grudges and feuds — which were passed on to his heirs. The game permitted up to four generations of knights to live and die during Arthur’s long reign.

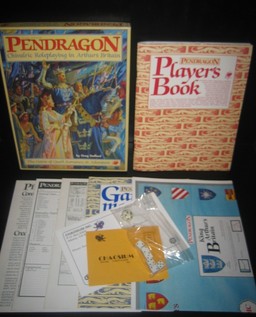

The game box came packed with an 88-page Player’s Book, a 16-page Gamemaster’s Book, and a beautiful 22″ by 30″ map of Britain complete with Roman roads, flags, kingdoms, cities, castles, keeps, rivers, mountains, fortified walls, forests, abbeys, battle sites, and more.

The game also largely dispensed with typical D&D monsters — orcs, goblins, hobgoblins, etc — in favor of natural and mythical creatures of legend, like avancs, barguests (um, what?), giants, kelpies, spriggans, unicorns, yales, and the Questing Beast. Never fear; elves and dwarves still made this list (though not completely as Tolkien described them).

Pendragon was immediately successful. Indeed, of the entire line of promising games Chaosium published in that era, is has endured the longest.

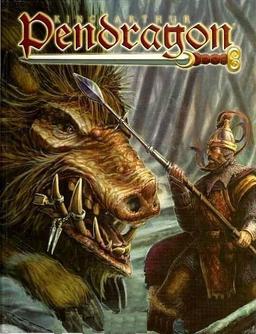

It has spawned multiple editions, from multiple publishers, over the last three decades. The newest, Pendragon 5th Edition, was released in a deluxe hardcover edition by Arthaus in December, 2005.

It has spawned multiple editions, from multiple publishers, over the last three decades. The newest, Pendragon 5th Edition, was released in a deluxe hardcover edition by Arthaus in December, 2005.

The various new editions offer considerable revisions and enhancements, of course, and they’re well worth a look. But for my money, it’s the many fine supplements and adventures released over the years that really make Pendragon special.

Chaosium brought their unique blend of energy and creativity to the Pendragon line for many years, releasing dozens of major products. A few of my favorites are Phyllis Ann Karr’s The King Arthur Companion, Tales of the Spectre Kings, Knights Adventurous, Land of Giants, The Boy King, and Perilous Forests.

That tradition continued as the game passed from publisher to publisher. Perhaps the ultimate supplement, The Great Pendragon Campaign, a massive 400-page hardcover written by Greg Stafford, was published by White Wolf in August 2006. It’s well worth a look by any fan of the game — or Arthurian fiction in general.

Pendragon — and over 30 supplements — are available in PDF format at DriveThruRPG. You can get the a scan of the original boxed version for just $9.99 and the 5th Edition for just $14.99.

Chaosium and its sister publisher Green Knight Publishing did more than just bring Arthurian fantasy fans into role playing and rejuvenate interest in King Arthur among role players. They also published a fine range of new and long-neglected Arthurian fantasy in handsome new editions. We’ve covered many of those releases here over the years, including The Life of Sir Aglovale de Galis by Clemence Housman and and The Merriest Knight, the collected Arthurian tales of Theodore Goodridge Roberts.

If you’re interested in more on Chaosium, there’s a fine overall history at RPG.Net.

Pendragon was written by Greg Stafford and published by Chaosium in 1985. According to the catalog inside the box, it was originally priced at $21.95. I bought my copy on eBay for $8.

[…] mystery, superhero, and many others. There were gangster games (Gangbusters), Arthurian games (Pendragon), games based on popular action films (Indiana Jones, James Bond), and westerns (Boot Hill). There […]

[…] There are lots of retellings of Dracula out there (just in the last two weeks William Patrick Maynard covered of Marvel’s Dracula, Lord of the Undead, James Maliszewski examined Bela Lugosi’s turn as Count Dracula in the 1931 Universal film, and John R. Fultz looked at NBC’s new series Dracula.) Same with Sherlock Holmes (see the trailer for Season Three of BBC One’s adaptation here), and the Tales of King Arthur and his noble knights (examples from the past two weeks here and here). […]

[…] with a new game focused on pirates, or science fiction, or the Bronze Age, or the Wild West, King Arthur, horror movies, the fall of Moria, the Federation, Middle Earth, Jack Vance’s Dying Earth, […]