The Magic Goes Away by Larry Niven

A swordsman battled a sorcerer once upon a time. In that age such battles were frequent. A natural antipathy exists between swordsmen and sorcerers, as between cats and small birds, or between rats and men. Usually the swordsman lost, and humanity’s average intelligence rose some trifling fraction. Sometimes the swordsman won, and again the species was improved; for a sorcerer who cannot kill one miserable swordsman is a poor excuse for a sorcerer.

So begins “Not Long Before the End” (1969), the first story in Larry Niven’s The Magic Goes Away series. His approach to swords & sorcery is the same as the one he brought to the hard science fiction he’s best known for: extravagant and colorful yet built on a framework of logic.

As you might infer from the tone of the quote, he also has a bias against the warrior hero typical of the genre and in favor of the sorcerer. In the short story above, its sequel “What Good Is a Glass Dagger?”, and the short novel The Magic Goes Away, he chronicled the adventures of a sorcerer called Warlock in a pre-historic Earth located somewhere to the right of Robert E. Howard’s Hyboria.

Niven’s starting point was to theorize how magic might work in a rational way. In his model, sorcery is powered by mana, a finite source. Instead of telling stories of the glory days when wizards built flying castles, and dragons and gods walked the earth, these tales are set in the magical world’s fading days. It’s a clever setup and one that drew me in enough to read the whole trilogy this past week.

“Not Long Before the End” is an inversion of the too-common S&S story of barbarian swordsman rescues girl from wicked sorcerer. Here Warlock discovers the nature of mana and realizes it’s running out.

In the course of his experiments to understand the relationship between magic and mana, the wizard created a magical wheel that, when set to spinning, uses up the mana in its immediate area, stopping only when the mana is exhausted. This knowledge becomes important when Belhap Sattlestone Wirldess ag Maracloat roo Cononson, known as Hap, armed with the demonic sword Glirindree, attempts to rescue the beautiful girl he believes is imprisoned by Warlock.

Unfortunately for Hap, Sharla is no prisoner, but Warlock’s wife. Twisting the S&S tropes is always a good thing and Niven does it with humor.

Unfortunately for Hap, Sharla is no prisoner, but Warlock’s wife. Twisting the S&S tropes is always a good thing and Niven does it with humor.

The sequel, “What Good Is a Glass Dagger?” (1972), has a great title but is a bit of a mess. Warlock’s discovery of mana and its properties has become common knowledge and the world’s order has been upset. The first part of the story is about an Atlantean werewolf named Aran trying to steal the Warlock Wheel. He represents a pacifist faction that hopes the wheel can be used to stop war.

Later in the story, Warlock learns another sorcerer has discovered that murder — though not killing during war — creates mana. With the help of a young wizard, he spends years hunting down the necromancer, ultimately tracking him to the city where a now middle-aged Aran lives as a rug merchant.

Unfortunately, the brief clever first part of “What Good Is a Glass Dagger?” is linked to the grim final part by a dull middle section. Too many pages are wasted on describing the fallout of Aran’s first encounter with Warlock. It serves a purpose in laying groundwork for their later meeting, but it slows things down too much. The story isn’t fast-paced to begin with, and the lackluster midsection only bogs it down.

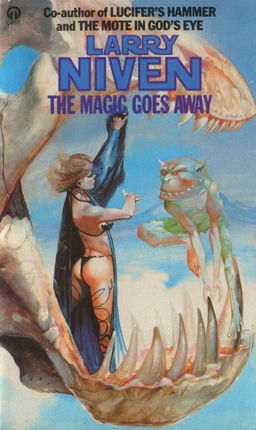

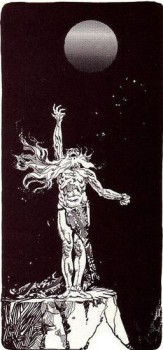

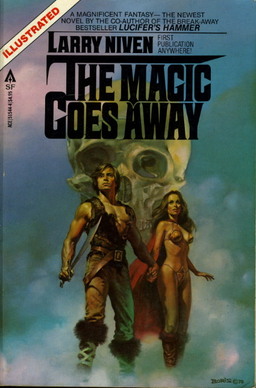

The Magic Goes Away (1978), massively illustrated (as touted on the cover) by Esteban Maroto, is set decades after the events in the two short stories. Warlock’s worst fears about the mana crisis have come true.

The novel opens with Orolandes, Achaean warrior and sole survivor of the invasion of Atlantis, washing ashore. His actions helped lead to the sinking of the island kingdom and he is racked with guilt. Hoping to find answers, and perhaps some redemption, he sets off in search of wizards and magic for help.

Meanwhile, Warlock has sent out a call to all the world’s remaining sorcerers, but only ten respond and only three are able to join him at his conference: his associate Clubfoot, the witch Mirandee, and the sorcerer Piranther. Orolandes hears of the conference and smashes his way in.

Meanwhile, Warlock has sent out a call to all the world’s remaining sorcerers, but only ten respond and only three are able to join him at his conference: his associate Clubfoot, the witch Mirandee, and the sorcerer Piranther. Orolandes hears of the conference and smashes his way in.

Even before Atlantis sank, the mana crisis was coming to a head. Magical creatures were fading away as unicorns gave birth to normal horses and dragons died. Nations built on magic were no longer able to fend off barbarian armies. Magic’s end times had definitely been entered.

The conferees devise an audacious plan to replenish the Earth’s mana supply. Knowing that the majority of mana came from meteorite debris, the wizards conclude the moon must be a tremendous source of power. The wizards see a strong warrior as an asset in a world weak in magic, and set out with Orolandes in tow.

Larry Niven, at his best, has created some of the most potent images in sci-fi. It’s his greatest talent as a writer. Mental pictures from Ringworld (1970) and The Mote in God’s Eye (1974) still blow me away.

That talent for imagery abounds in both stories and the novel under review here. Niven brings a wild creativity to even his lesser work. He’s great at creating memorable scenes both on a small scale, such as Hap’s relentless assault on Warlock and the wizard’s responses, as well as the grand, like the god Roze-Kattee growing so big it pierces the atmosphere.

“Not Long Before the End” is successful because it’s short and tart. It’s sufficient that the characters exist only as tropes for the author to play with so he can create a magical system to suit his sense of logic and show the power of brain over brawn.

The good parts of “What Good Is a Glass Dagger?” are successful for the same reasons. Much of Niven’s writing is about puzzles and applying logic to solve them, whether it’s how to survive a deadly alien attack in “The Warriors” or killer gravitational forces in “Neutron Star.”

The good parts of “What Good Is a Glass Dagger?” are successful for the same reasons. Much of Niven’s writing is about puzzles and applying logic to solve them, whether it’s how to survive a deadly alien attack in “The Warriors” or killer gravitational forces in “Neutron Star.”

Applying that same sort of game-playing and rational thinking to fantasy is an intriguing idea and in short bursts it works.

The Magic Goes Away suffers from dull, explanatory sections and especially dry characterization. Warlock, Orolandes, and company never become more than stereotypes.

As I read, I started wondering which would win the battle for my mind — the cool, exciting ideas or the flat characters. It’s something I’ve experienced before reading Larry Niven and here it’s kind of a tie, which is a shame.

Mirandee’s a sexy witch and Orolandes is a morose warrior, no more, no less and so on with everyone else. The fates of the various characters left me spectacularly unmoved, as they had never become more to me than ink on a page.

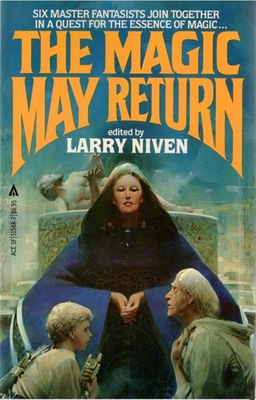

There’s a sequel volume called The Magic May Return, featuring stories by other authors, including Fred Saberhagen and Poul Anderson (as well as “Not Long Before the End”). I like the world Niven created and the conceit behind it enough that I’d be willing to revisit it, particularly in other hands.

All three stories are available in the collection The Time of the Warlock. I recommend the hard copies because of the cool pictures.

A knife always works.

Come to think of it, this is the only Niven I’ve read that didn’t have me struggling with disbelief.

Just purchased a copy on eBay, so thanks for the write-up!

@ Jeff – What, breeding for luck doesn’t work for you?

@ Scott – Maroto’s pictures are pure seventies pulp glory.

[…] scientific explanations for what fantasy-flavored worlds of dragons and magic. Meanwhile, in The Magic Goes Away and related stories, hard science fiction author Larry Niven treated magic as science and […]

[…] provided scientific explanations for fantasy-flavored worlds of dragons and magic. Meanwhile, in The Magic Goes Away, hard science fiction author Larry Niven treated magic as science and investigated all the […]