Inspiration and Emulation, Tolkien and Gygax

To say that I have an abiding interest in the relationship between tabletop roleplaying games and the literary inspirations of their creators is something of an understatement.

To say that I have an abiding interest in the relationship between tabletop roleplaying games and the literary inspirations of their creators is something of an understatement.

Notice, though, that I said “inspirations” rather than another word that frequently gets bandied about when discussing the relationship between literature and RPGs – emulation. I can’t recall precisely when I first heard the term “emulation” used in the context of roleplaying games, but I’d be surprised if it were before the late 1980s. That’s about a decade after I entered the hobby, so my memory is admittedly fuzzy and I could well be mistaken. On the other hand, I heard the term “inspiration” a great deal, most notably in (you knew this was coming!) Gary Gygax’s 1979 Appendix N and the “Inspirational Source Material” found in the 1981 Tom Moldvay-edited edition of Dungeons & Dragons. Back in those days, game creators often talked about the books whose characters, plots, and ideas had fired their imaginations to such a degree that they decided to create a RPG that drew on them; they still do.

“Emulation” is something different. It’s one thing, I believe, to create a fantasy roleplaying game inspired by, say, Robert E. Howard’s stories of Conan the Cimmerian, but an entirely different thing to create a roleplaying game intended to emulate the adventures of Conan. Emulation implies a degree of fidelity to its literary sources (at least thematically), as well as some means – whether rules or advice – to ensure that experience of playing the game imitates that source material. An example of what I’m talking about that comes immediately to mind is Chaosium’s Call of Cthulhu RPG. While its rules do not explicitly talk about emulation, they do include game mechanics for the loss of sanity that results from encounters with blasphemous tomes and eldritch horrors. The creator of a game that’s merely inspired by some literary source is under no such obligations. After all, inspiration can take many forms, many of which do not include aping one’s sources of inspiration.

I mention all of this as a prologue to a large, more contentious discussion, namely the place of the works of J.R.R. Tolkien in the creation of Dungeons & Dragons.

I don’t think it can be reasonably denied that both The Hobbit and The Lord of the Rings had a profound impact on the creation, development, and subsequent success of D&D. As I’ve noted before, the “Fantasy Supplement” of Chainmail, which is D&D‘s immediate forebear, draws attention to its utility in “refight[ing] the epic struggles related by J.R.R. Tolkien.”

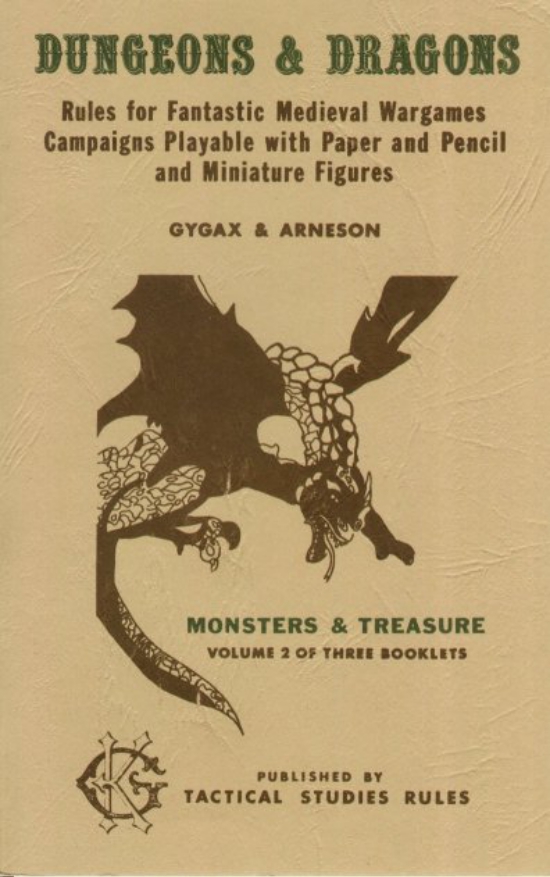

Furthermore, the premier edition of D&D included the options of playing not only dwarves and elves, both of which have strong folkloric antecedents, but also hobbits (later called “halflings”), which do not. There are many other references to Tolkien throughout those little brown books published in 1974, from orcs and ents to wights and balrogs, among others. Consequently, it’s no surprise that, for many gamers, Tolkien is viewed as the primary inspiration of Dungeons & Dragons and they are reluctant to believe otherwise – and with good reason.

Furthermore, the premier edition of D&D included the options of playing not only dwarves and elves, both of which have strong folkloric antecedents, but also hobbits (later called “halflings”), which do not. There are many other references to Tolkien throughout those little brown books published in 1974, from orcs and ents to wights and balrogs, among others. Consequently, it’s no surprise that, for many gamers, Tolkien is viewed as the primary inspiration of Dungeons & Dragons and they are reluctant to believe otherwise – and with good reason.

However, I think it worth noting that, in his foreword of November 1, 1973, when Gary Gygax is explaining just what D&D is, he makes no mention of Tolkien. Instead, he references “Burroughs’ Martian adventures,” “Howard’s Conan saga,” “the de Camp & Pratt fantasies,” and “Fritz Leiber’s Fafhrd and the Gray Mouser.” Most of the borrowings from Middle-earth occur in Volume 2 of the game, Monsters & Treasure, which only makes sense as many of Tolkien’s creatures are easily dropped into almost any fantasy setting. Of course, Gygax does something similar with Burroughs; D&D‘s wilderness encounter tables include tharks, Martians of every hue, apts, banths, thoats, white apes, and more. I think this makes it readily apparent that, far from being the pre-eminent inspiration of the game, Middle-earth is one of many and not necessarily the greatest one.

Gygax himself addressed this very point in an 1974 article appearing in the quarterly wargames magazine La Vivandière, published by Palikar Publications of Minneapolis. The article, “Fantasy Wargaming and the Influence of J.R.R. Tolkien,” may well be the first time Gygax specifically addresses the question of how much influence Tolkien had on his conception of Dungeons & Dragons. Please take note of the publication year; it’s the same year that D&D first appeared. More importantly, it’s several years before Tolkien Enterprise’s cease-and-desist order was sent to TSR regarding the inclusion of monsters clearly “borrowed” from the works of the good professor. I say “more importantly,” because it’s quite common for later commentators to argue that Gygax only downplayed the role of Tolkien in inspiring D&D because he was fearful of a full-blown lawsuit. While I’m sure such legal concerns played some role in his later statements, the fact that Gygax was already saying things like this shortly after the game was released suggests to me that he wasn’t wholly disingenuous in his feelings.

Let’s consider the following quotation from the article, in which Gygax discusses the debts he owes to various writers:

What other sources of fantasy can compare to J.R.R. Tolkien? Obviously, Professor Tolkien did not create the whole of his fantasies from within. They draw upon mythology and folklore rather heavily, with a few highly interesting creations which belong solely to the author such as the Nazgul, the Balrog, and Tom Bombadil. All of the other creatures are found in fairy tales by the score and dozens of other excellent writers who create fantasy works themselves: besides Howard whom I already mentioned, there are the likes of Poul Anderson, L. Sprague de Camp and Fletcher Pratt, Fritz Leiber, H.P. Lovecraft, A. Merritt, Michael Moorcock, Jack Vance, and Roger Zelazny — there are many more, and the ommission [sic] of their names here is more of an oversight than a slight. In the creation of Chainmail and Dungeons & Dragons the concepts of not a few of such authors were drawn upon. This is principally due to the different aims of a fantasy novel (or series of novels) and a rule book for fantasy games. The former creation is to amuse and entertain the reader through the means of the story and its characters, while the latter creates characters and possibly a story which the readers then employ to amuse themselves. In general the “Ring Trilogy” is not fast paced, and outside the framework of the tale many of Tolkien’s creatures are not very exciting or different.

There are a number of fascinating details here, but what I find most interesting is that what Gygax has written here is very much in line with what he’d write years later, particularly with regards to the slowness of pace in Tolkien’s books. Elsewhere, he notes that “quite a few readers [of Dungeons & Dragons] complained that the work did not follow Tolkien!” Apparently, these readers were expecting that, simply because the game included elements borrowed from Middle-earth, the game itself would emulate them.

This charge was repeated for years afterwards, much to Gygax’s dismay. Witness the article by Bill Seligman in issue #5 of The Dragon (March 1977), “Gandalf Was Only A Fifth Level Magic User,” in which it’s suggested that something might be “wrong” with D&D because it does not adequately model a character like the Grey Wanderer.

This charge was repeated for years afterwards, much to Gygax’s dismay. Witness the article by Bill Seligman in issue #5 of The Dragon (March 1977), “Gandalf Was Only A Fifth Level Magic User,” in which it’s suggested that something might be “wrong” with D&D because it does not adequately model a character like the Grey Wanderer.

My own feeling is that is Gygax simply wasn’t all that taken with Tolkien or his creations, at least not to the degree that other fantasy enthusiasts were in the early 1970s. He even alludes to this in the article, when he jokingly calls himself a “foul blasphemer” for daring not “to consider Tolkien as the ultimate authority and his writings as sacrosanct.” I suspect his inclusion of orcs and ents and so forth was largely an attempt at “marketing,” to latch on to an existing fad and use it to help increase D&D‘s popularity. I think this comes through when you read Volume 1’s description of hobbits as a character option, which begins “Should any player wish to be one …” Maybe I read too much into that clause, but it seems to me that there’s a note of disdain or at least incredulity to it – “If someone is really foolish enough to want to play a hobbit…” In the article, Gygax seems to support this interpretation:

Tolkien includes a number of heroic figures, but they are not of the “Conan” stamp. They are not larger-than-life swashbucklers who fear neither monster nor magic. His wizards are either ineffectual or else they lurk in their strongholds working magic spells which seem to have little if any effect while their gross and stupid minions bungle their plans for supremacy. Religion with its attendant gods and priests he includes not at all. These considerations, as well as a comparison of the creatures of Tolkien’s writings with the models they were drawn from (or with a hypothetical counterpart desirable from a wargame standpoint) were in mind when Chainmail and Dungeons & Dragons were created.

Take several of Tolkien’s heroic figures for example. Would a participant in a fantasy game more readily identify with Bard of Dale? Aragorn? Frodo Baggins? or would he rather relate to Conan, Fafhrd, the Grey Mouser, or Elric of Melnibone? The answer seems all too obvious.

Here, I think, we reach the crux of the matter. While recognizing him as “the most influential fantasy writer of our time,” Gygax simply does not find Tolkien to his tastes. He would much rather read Howard or Leiber or even Moorcock, whose protagonists are of the “stamp” he finds most compelling. And there’s nothing wrong with that! Speaking as an unabashed devotee of Tolkien, I see nothing unreasonable in Gygax’s opinions, even if I don’t necessarily share them. If anything, I find his perspective refreshing, as it’s both honest and insightful. I say “insightful” because it provides us with a window into the mind of one of the creators of Dungeons & Dragons and how he viewed the game’s relationship to the literary sources that inspired him to create it. Would that we had similar insights into the minds of other early RPG creators!

Though at a much later date, Gygax says in Dragon Magazine article (somewhere between issues 95 and 98) that Tolkien had almost no influence upon his creation and development of DnD.

The prior evidence you cite here seems to strengthen the case that indeed Tolkien was not Gygax’s particular cup of tea.

James,

I remember something similar (although, unlike James Maliszewski, I am wholly incapable of providing lengthy quotes!)

If I remember correctly, Gygax panned LotR, but spoke of grudging admiration for The Hobbit.

John,

Maybe I’ll dig up that Dragon issue and report back.

Yep — Gygax liked the Hobbit but not so much LotR, and he more or less admitted to adding the Tolkien races & creatures just to capitalize on the popularity of LotR even though the game itself was much more Howard/Burroughs/Leiber.

Having said that (and I may have said this here before), I do think there was one critical thing Gygax took from LotR that really made D&D what it is today: The concept of the “adventuring party” where you have a bunch of different characters with discrete roles working together on a more-or-less equal basis. Most classic sword & sorcery fiction is just about a hero, or a hero & a sidekick; by bringing in the adventuring party, Gygax created a scenario where you could have four or five or six people sitting around the table and taking an equal role in the adventure.

> I do think there was one critical thing Gygax took from LotR that really made D&D what it is today: The concept

> of the “adventuring party” where you have a bunch of different characters with discrete roles working together on

> a more-or-less equal basis. Most classic sword & sorcery fiction is just about a hero, or a hero & a sidekick; by

> bringing in the adventuring party, Gygax created a scenario where you could have four or five or six people sitting

> around the table and taking an equal role in the adventure.

Joe,

!!!

I’ve never seen that attributed to Tolkien before… and yet, it seems obvious now that you say it, doesn’t it?

I find it hard to believe we can’t find a popular counter-example that precedes Tolkien, though. Quest fantasy is, after all, as old as fantasy itself. And one of the most basic elements of the Quest is the team that the hero gathers together on her journey.

Still… when a ranger, thief, wizard, elf and a dwarf gather together in a fellowship before venturing into danger… where are you going to find a more archetypal example of that than Tolkien?

His criticisms of Tolkien are as shallow as Moorcock’s but everyone has a right to an opinion. His other remarks, however, are just dumb.

Could Gygax be more wrong about who people want to imitate? The halfling thief and the Aragorn pastiche were the two most common player characters found back when I played. (I guess its all dual wielding dark elves now – kids these days!)

And the thing I despise most about DnD is the inability to create many of the heroic characters from classic sword and sorcery because DnD class rules are so restrictive. The rules lead the character parties to look more like the Fellowship and not Kane or Elric (can’t use that two-handed sword and cast a spell, mate). So the rules he created don’t even lend themselves to create many of the characters he said people want to imitate.

Found that article I was referencing: it’s from Dragon Magazine #95 (March, 1985). The official article title is “The Influence of J. R. R. Tolkien on the D&D and AD&D Games: Why Middle Earth is Not Part of the Game World.” By Gary Gygax.

I’ll share just a couple of quotes:

“The popularity of Professor Tolkien’s fantasy works did encourage me to develop my own. But while there are bits and pieces of his works reflected in hazily in mine, I believe that his influence, as a whole, is quite minimal.” (p. 12)

“A careful examination of the games will quickly reveal that the major influences are Robert E. Howard, L. Sprague de Camp and Fletcher Pratt, Fritz Leiber, Poul Anderson, A. Merritt, and H. P. Lovecraft. Only slightly lesser influence came from Roger Zelazny, E. R. Burroughs, Michael Moorcock, Philip Jose Farmer, and many others. Though I thoroughly enjoyed The Hobbit, I found the “Ring Trilogy” . . . well, tedious. The action dragged [. . . .]”

That last comment is good evidence for Maliszewski’s claim that Gygax just wasn’t all that taken with Tolkien.

There were some tolkien influences. Why else were rangers originally required to be Good?

John — As I think about it, I suppose the Argonauts might be considered a precursor to the adventuring party — but even that seems a bit different somehow.

> Found that article I was referencing: it’s from Dragon Magazine #95 (March, 1985).

James,

Nice work tracking down that quote! Notch one down for genuine scholarship here at Black Gate.

Glad to know I’m not crazy, too. 🙂

> So the rules he created don’t even lend themselves to create many of the characters he said people want to imitate.

Tyr,

True! Although, Gygax WAS saddled with trying to create some play balance between character classes, not just create a single character class that everyone would want to play.

Considering the ultimate success of his efforts, I think I’d be a fool to mock his game design skills at this point. His efforts to create a game that re-created true sword & sorcery… now that’s fair game.

> There were some tolkien influences. Why else were rangers originally required to be Good?

Mary,

Good point!

> I suppose the Argonauts might be considered a precursor to the adventuring party — but even that seems a bit different somehow

Joe,

Nice call. Even more famous than Lord of the Rings, to boot!

Still, I don’t remember the crew of the Argo having the diverse skill set of the Fellowship of the Ring. Those nine fellows really are poster children for the archetypal dungeoning party.

Jason’s Argonauts is a good call. Other potential inspirations for the multi-skilled adventuring party:

– Robin Hood’s Merrie Men

– Doc Savage’s five stalwarts

– Any American fiction about a WWII squad: novels, movies, comics

Pretty much a standard fictional trope in mid-20th century genre fiction.

Yeah, the WWII squad is probably a good model — the scout, the explosives guy, the medic, the marksman, etc. Or maybe the guys in a caper/heist film (with much the same roles, in fact).

[…] James Maliszewski has been exploring in his ongoing series on Appendix N — as well as Mordicai Knode and Tim Callahan, who are examining one Appendix N […]

[…] Inspiration and Emulation, Tolkien and Gygax […]

John,

I was going to mention Doc Savage and the Fantastic Five, but Lawrence Schick beat me to it.

I don’t think anyone mentioned this, but as a GM, trying to run RPG sessions for more than one player without the party structure requires incredible tolerance on the non-hero/non-focus players. It is not difficult to imagine that one of the core design criteria for Dungeons and Dragons was to maximize the number of players able to participate at any one time.

Fritz.

[…] to your other questions, James Maliszewski’s post on Appendix N and Moldvay B52 is probably better than anything I could write on that […]

[…] wedge his face-tentacles into everything you love. He’s inspired such disparate works as Dungeons And Dragons, Evil Dead, and even Conan The Barbarian — and yet, very few of his works have been directly […]

[…] wedge his face-tentacles into everything you love. He’s inspired such disparate works as Dungeons And Dragons, Evil Dead, and even Conan The Barbarian — and yet, very few of his works have been directly […]

[…] wedge his face-tentacles into everything you love. He’s inspired such disparate works as Dungeons And Dragons, Evil Dead, and even Conan The Barbarian — and yet, very few of his works have been directly […]

[…] wedge his face-tentacles into everything you love. He’s inspired such disparate works as Dungeons And Dragons, Evil Dead, and even Conan The Barbarian — and yet, very few of his works have been directly […]

[…] wedge his face-tentacles into everything you love. He’s provoked such disparate drudgeries as Dungeons And Dragons , Evil Dead , and even Conan The Barbarian — and yet, very few of his wreaks ought to […]

[…] Dungeons & Dragons] most of the Tolkien-influenced material was added to the mix to broaden the appeal of the underlying fantasy action-adventure …”— Gary […]