The Cold Edge of Forever, II: City

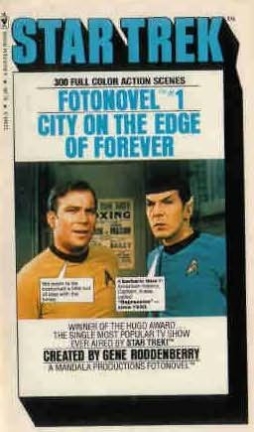

This is the second part of my attempt to write about Star Trek, and specifically the episode “The City on the Edge of Forever.” For reasons which I hope will soon make sense I started off yesterday by writing about the 1954 short story “The Cold Equations.” What I’m about to try to do is tie that into a discussion of the Trek episode, and then go on to look at that episode in the context of the show overall. I am going to assume in what follows that you’re familiar with the episode (the plot synopsis is here; if it helps, it’s the one with the Guardian of Forever, where Kirk and Spock travel back to 1930), and that you know things like who Captain Kirk is, and who Mister Spock is, and so on and so forth. This I think is a fair assumption. Everybody knows these characters. Which is a part of why I want to talk about the episode, and its context. So before anything else, I want first to talk about the exercise of unknowing them. (And as an aside, the poster at right is by artist Juan Ortiz, who did an image for every episode of the original series. Worth taking a look at, and the whole run has been collected in a single book.)

This is the second part of my attempt to write about Star Trek, and specifically the episode “The City on the Edge of Forever.” For reasons which I hope will soon make sense I started off yesterday by writing about the 1954 short story “The Cold Equations.” What I’m about to try to do is tie that into a discussion of the Trek episode, and then go on to look at that episode in the context of the show overall. I am going to assume in what follows that you’re familiar with the episode (the plot synopsis is here; if it helps, it’s the one with the Guardian of Forever, where Kirk and Spock travel back to 1930), and that you know things like who Captain Kirk is, and who Mister Spock is, and so on and so forth. This I think is a fair assumption. Everybody knows these characters. Which is a part of why I want to talk about the episode, and its context. So before anything else, I want first to talk about the exercise of unknowing them. (And as an aside, the poster at right is by artist Juan Ortiz, who did an image for every episode of the original series. Worth taking a look at, and the whole run has been collected in a single book.)

Lately I’ve been watching the first season of Star Trek week by week, on a TV network that airs old shows from the 50s through 70s. Seeing the series in that context means seeing it as part of the fabric of its time. Some series, I`ve found, become very different: the original Twilight Zone, always a good show, becomes downright mind-bending. Watching Trek in that way I find myself caught up in the craft of the writing, direction, and (yes) acting; and I seem to forget everything I know about what happens outside of the show I’m seeing.

There’s a thrilling sense of discovery, of a slow unveiling of the world of the show, as we learn a bit about the Federation here and a bit about its mysterious enemies there and a little about the ‘Vulcanians’ over there. Seeing episodes I thought I knew as though for the first time, I’m continually surprised. I never noticed that the improvised cannon Kirk uses against the Gorn in “Arena” visually echoes a futuristic rocket launcher he used earlier in the show, so when he throws away his knife and refuses to kill the lizard-man it’s almost like a rejection of a whole tradition of military technology. But more surprising than the things I never noticed are the things that have been set to the side by later writers. I never realised, for example, that the cosmically-powerful Organians from “Errand of Mercy” really are just a bunch of silly old buffers who just want the damn kids to turn down the racket and get off their lawn; but the fact is even after they reveal their true power, that’s how they act, like slightly-cranky grandparents trying to make small children see reason.

There’s a thrilling sense of discovery, of a slow unveiling of the world of the show, as we learn a bit about the Federation here and a bit about its mysterious enemies there and a little about the ‘Vulcanians’ over there. Seeing episodes I thought I knew as though for the first time, I’m continually surprised. I never noticed that the improvised cannon Kirk uses against the Gorn in “Arena” visually echoes a futuristic rocket launcher he used earlier in the show, so when he throws away his knife and refuses to kill the lizard-man it’s almost like a rejection of a whole tradition of military technology. But more surprising than the things I never noticed are the things that have been set to the side by later writers. I never realised, for example, that the cosmically-powerful Organians from “Errand of Mercy” really are just a bunch of silly old buffers who just want the damn kids to turn down the racket and get off their lawn; but the fact is even after they reveal their true power, that’s how they act, like slightly-cranky grandparents trying to make small children see reason.

I never noticed how often mind-altering substances seem to pop up in the show, usually in a negative way: the Venus drug of “Mudd’s Women,” the spores of “This Side of Paradise.” I never noticed how the show was haunted by World War Two: starship combat as analog for submarine-warfare in “Balance of Terror,” eugenics and the Eugenics Wars in “Space Seed.” In fact, I never noticed that, according to the timeline “Space Seed” establishes, a young Khan Noonien Singh would, in theory, already be alive at the time the episode was first broadcast — that the show suggested the breeding programs that were to lead to the Eugenics Wars of the 1990s were already underway. And then the other week I watched “City On the Edge of Forever;” and again there is a mind-altering drug, again there is mention of World War Two. And I noticed as well how oddly the episode fits with the series as it later developed. And, in noticing this, I found myself reminded of “The Cold Equations.”

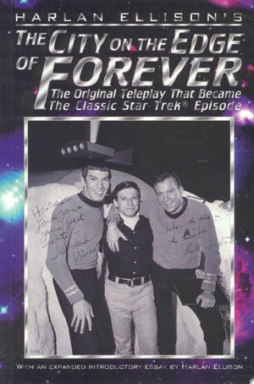

(I should note, as I write about this episode, that I intend to discuss what actually aired. There was famously a controversy that erupted over changes made to the script as first written by Harlan Ellison. I will say that I’ve read Ellison’s original script, and it’s an interesting contrast, worth talking about in its own right. But I want to look at the show that aired, complete with odd fragments of earlier drafts sticking out here and there.)

I think the episode’s actually much stronger than the prose story. It’s a different thing, longer, bigger, with many more aspects; but I think in many ways a better thing. In both stories a spaceman hero has to sacrifice a female (or at least see her sacrificed) for the greater good, in accordance with natural law. But “City” seems to have an internal coherence that “The Cold Equations” lacks. As I noted, people have been picking holes in the internal logic of the short story perhaps since it was published. I’ve not seen a similar level of debate over the internal logic of “City on the Edge of Forever.” But I think both stories aim at fundamentally the same thing: a science-fiction tragedy, in which an innocent is sacrificed according to iron laws of necessity. And in which the supposed hero turns out to be helpless. (I have not seen a discussion about sexism and gender roles in “City” the way one has emerged around “The Cold Equations.” There might well be one, and I’ve missed it; but I wonder if this isn’t a case where the simple presence of Uhura changes the way one perceives the story as a whole — unlike the prose story, there’s another female in the tale, however minor a part she plays.)

I think the episode’s actually much stronger than the prose story. It’s a different thing, longer, bigger, with many more aspects; but I think in many ways a better thing. In both stories a spaceman hero has to sacrifice a female (or at least see her sacrificed) for the greater good, in accordance with natural law. But “City” seems to have an internal coherence that “The Cold Equations” lacks. As I noted, people have been picking holes in the internal logic of the short story perhaps since it was published. I’ve not seen a similar level of debate over the internal logic of “City on the Edge of Forever.” But I think both stories aim at fundamentally the same thing: a science-fiction tragedy, in which an innocent is sacrificed according to iron laws of necessity. And in which the supposed hero turns out to be helpless. (I have not seen a discussion about sexism and gender roles in “City” the way one has emerged around “The Cold Equations.” There might well be one, and I’ve missed it; but I wonder if this isn’t a case where the simple presence of Uhura changes the way one perceives the story as a whole — unlike the prose story, there’s another female in the tale, however minor a part she plays.)

“The Cold Equations” and “City On the Edge of Forever” have more in common than the death of their female characters. They also have the impotence of their male characters. These stories are, in this reading, dramas of powerlessness. The male heroes are made to face their helplessness, to face their limits, in the inevitable death of the females. I suspect that this particular manifestation of male helplessness, the death of a woman or child in one’s care, was particularly traumatic for men in the 1940s and even 60s because of the explicitly patriarchal way that manliness was constructed at those times: perhaps rather more than in the 21st century, the man was supposed to protect the woman and the child, and his failure is a failure as a man at a basic level.

So along those lines, given the similarity of some aspects of these stories’ structure, it’s worth looking at the differences, and why (at least to me) they feel so different. I want to start with one of the most crucial differences: in “The Cold Equations,” Marilyn knows what’s happening. She knows she’s looking at her inevitable death, and ultimately comes to accept it. She enters the airlock willingly. In “City,” neither Kirk nor Spock tell Edith Keeler what they’ve learned about her future, and what has to happen. You could argue that this is part of the logic of her fate: what happens to her has to happen accidentally, in order for the timeline to be preserved. But this is debateable; if she died in something that appeared to be an accident, or indeed died at any point at approximately the right time, surely things would work out essentially the same.

You could also argue that Kirk and Spock couldn’t risk telling Keeler the truth because it’d further endanger the timeline. But watching this episode again, I was surprised at how much Kirk told her about himself. He validates her belief in the future — and surely one of the most touching things in the episode is Keeler’s seemingly-naive belief in a future that turns out to be exactly correct — but doesn’t come out and tell her everything. Why? I came to believe it’s because he knew what she’d do if he did. She is an idealist; she is strong-willed, and, running a mission in the middle of the Great Depression, used to looking with clear eyes at unpleasant situations. If she knew the whole story of what was to come and what hinged on her choice, it’s impossible to imagine that she wouldn’t insist on seeing things through as history originally ran. In order to bring about the future she most dearly wants, she has to die. What other choice would she have? Could she take a chance on going on living, possibly ruining all her hopes and dreams?

You could also argue that Kirk and Spock couldn’t risk telling Keeler the truth because it’d further endanger the timeline. But watching this episode again, I was surprised at how much Kirk told her about himself. He validates her belief in the future — and surely one of the most touching things in the episode is Keeler’s seemingly-naive belief in a future that turns out to be exactly correct — but doesn’t come out and tell her everything. Why? I came to believe it’s because he knew what she’d do if he did. She is an idealist; she is strong-willed, and, running a mission in the middle of the Great Depression, used to looking with clear eyes at unpleasant situations. If she knew the whole story of what was to come and what hinged on her choice, it’s impossible to imagine that she wouldn’t insist on seeing things through as history originally ran. In order to bring about the future she most dearly wants, she has to die. What other choice would she have? Could she take a chance on going on living, possibly ruining all her hopes and dreams?

More than this: set aside the tendency to view the characters and situations of the original show ironically. Consider Kirk as conceived, as written (and, yes, in these early episodes at least, as played). What other sort of woman could draw Kirk so strongly? And conversely, if she didn’t act according to her ideals, whatever the cost, how could Kirk continue to love her? So he doesn’t tell her. He doesn’t force the decision until the final moment, and then effectively keeps the decision for himself. On the one hand he keeps Keeler from having to will her own death. On the other hand, he’s also preserving the fiction of his own agency. Up to that point, he can tell himself he still has the power to do something. He can even save her from a spill on the stairs he knows won’t be fatal — because Spock’s determined that she dies in a traffic accident, not indoors — all the while hiding from himself his own powerlessness.

And, following from this, I think “City” brings out the sense of betrayal much more powerfully than “The Cold Equations.” The fetishising of physics in that story tend to absolve the pilot, Barton, of any responsibility. Everything in “City” tends in the other direction. Kirk tells Keeler that perhaps even more powerful than “I love you” are the words “let me help.” But that’s precisely what he doesn’t do. He doesn’t help her, and he doesn’t let McCoy help. The episode doesn’t let Kirk off the hook. The ending’s shattering precisely because the equations here aren’t cold. There is a responsibility. A failure. A promise, however implicit, that is broken.

And, following from this, I think “City” brings out the sense of betrayal much more powerfully than “The Cold Equations.” The fetishising of physics in that story tend to absolve the pilot, Barton, of any responsibility. Everything in “City” tends in the other direction. Kirk tells Keeler that perhaps even more powerful than “I love you” are the words “let me help.” But that’s precisely what he doesn’t do. He doesn’t help her, and he doesn’t let McCoy help. The episode doesn’t let Kirk off the hook. The ending’s shattering precisely because the equations here aren’t cold. There is a responsibility. A failure. A promise, however implicit, that is broken.

But if the level of awareness of the women sentenced to death is one of the main differences between the stories, it’s also worth noting another key difference: the question of causality. As I discussed yesterday, readers have debated for years the question of whether the situation of “The Cold Equations” is caused by Marilyn being foolish and immature or whether her society’s to blame. But the problem of “The City On the Edge of Forever” is caused largely by dumb luck — a drugged McCoy coming into conjunction with an active time portal — and then also by Keeler’s idealism. That is, to the extent that the problem has a cause, that cause isn’t a flaw or limit, but a virtue. One could argue that it’s a feminised kind of idealism, arguing for peace in a time of war, but the male characters certainly don’t fault her for it. “She was right,” Kirk says; “But at the wrong time,” observes Spock. One can argue with the simplified history the episode suggests, but however you slice it, this is not foolishness, it’s not wrongheadedness, it’s tragedy. It’s fate.

(But here’s an amusing question to think about: is the situation of “City” really dumb luck? It seems awfully coincidental that McCoy just happens to cause one of the most disastrous of all possible timeline changes by a single well-intentioned act. Even more coincidental that the woman he saved happens to be a woman who could attract Kirk so strongly. And perhaps especially coincidental in that McCoy got injected with the drug due to the time-distortion waves rocking the Enterprise at the start of the episode — which turn out to have been caused by the Guardian, for no obvious reason, and similarly which stop for no obvious reason. Is that fate? Or is it a guiding intelligence? Was the Guardian of Forever doing more than it let on? Did it set up events on the planet surface? Could it be that it saw that new potential users had wandered in to the area? Did it come up with a subtle way of letting them know about the risks involved in time travel? Or does it perhaps always create this sort of psychological stress on anyone who uses it? If Starfleet sets up a base camp of adventurer-historians around the Guardian intending to use it to study the past, do the academics eventually give up and go home after everybody who goes through the Guardian comes back to the present disturbed down to the core of their being? Or: from the perspective of an n-dimensional inhuman intelligence with a nontraditional and quite probably nonlinear relationship to time, the advent of the Enterprise is itself only another point along the timeline of the universe, and one that the Guardian can affect directly with its own words and actions, rather than indirectly, sending entities back through time. In other words: did the Guardian arrange the whole scenario in this episode, for the sake of selecting a specific future? Perhaps specifically to create certain psychological changes in Kirk?)

(But here’s an amusing question to think about: is the situation of “City” really dumb luck? It seems awfully coincidental that McCoy just happens to cause one of the most disastrous of all possible timeline changes by a single well-intentioned act. Even more coincidental that the woman he saved happens to be a woman who could attract Kirk so strongly. And perhaps especially coincidental in that McCoy got injected with the drug due to the time-distortion waves rocking the Enterprise at the start of the episode — which turn out to have been caused by the Guardian, for no obvious reason, and similarly which stop for no obvious reason. Is that fate? Or is it a guiding intelligence? Was the Guardian of Forever doing more than it let on? Did it set up events on the planet surface? Could it be that it saw that new potential users had wandered in to the area? Did it come up with a subtle way of letting them know about the risks involved in time travel? Or does it perhaps always create this sort of psychological stress on anyone who uses it? If Starfleet sets up a base camp of adventurer-historians around the Guardian intending to use it to study the past, do the academics eventually give up and go home after everybody who goes through the Guardian comes back to the present disturbed down to the core of their being? Or: from the perspective of an n-dimensional inhuman intelligence with a nontraditional and quite probably nonlinear relationship to time, the advent of the Enterprise is itself only another point along the timeline of the universe, and one that the Guardian can affect directly with its own words and actions, rather than indirectly, sending entities back through time. In other words: did the Guardian arrange the whole scenario in this episode, for the sake of selecting a specific future? Perhaps specifically to create certain psychological changes in Kirk?)

I’d say that “City” rises closer to genuine tragedy than “The Cold Equations” for a couple other reasons as well. As I’ve said, “City” feels like less of a rigged game. It’s actually just as rigged, as all stories are rigged for their own ends, but it comes off, to me, as less contrived. To an extent that’s a function of the bigger scope of the stories. “The Cold Equations” takes place entirely within the confines of a small spaceship; it’s a two-person play, with a few voices from offstage — heard over the radio. You could argue, I think, that the measure of how the story fails is in how it neither takes advantage of the two-people-in-confined-space set-up to generate dramatic tension, nor really consistently reaches an elegiac tone. In any event, “The City on the Edge of Forever” is wildly different: in (what would become) the great Star Trek tradition, it’s about exploration and solving mysteries. Strange time distortions are buffeting the Enterprise! Where are they coming from? An unexplored planet! What’s on the planet? A mysterious alien artifact! What does the artifact do? It lets you travel anywhere in space or time! Whoops, McCoy’s gone through it, where is he now? 1930! Okay, Kirk and Spock go after him, and what do they find? — And so on. The love-and-death tragic plot doesn’t kick in until fairly late; the ground’s been well-laid. All the exploration and adventure doesn’t distract from the tragic momentum of the second half of the story; somehow it prepares us for it, setting plots in motion that all come together at the right moment for maximum impact.

I’d say that “City” rises closer to genuine tragedy than “The Cold Equations” for a couple other reasons as well. As I’ve said, “City” feels like less of a rigged game. It’s actually just as rigged, as all stories are rigged for their own ends, but it comes off, to me, as less contrived. To an extent that’s a function of the bigger scope of the stories. “The Cold Equations” takes place entirely within the confines of a small spaceship; it’s a two-person play, with a few voices from offstage — heard over the radio. You could argue, I think, that the measure of how the story fails is in how it neither takes advantage of the two-people-in-confined-space set-up to generate dramatic tension, nor really consistently reaches an elegiac tone. In any event, “The City on the Edge of Forever” is wildly different: in (what would become) the great Star Trek tradition, it’s about exploration and solving mysteries. Strange time distortions are buffeting the Enterprise! Where are they coming from? An unexplored planet! What’s on the planet? A mysterious alien artifact! What does the artifact do? It lets you travel anywhere in space or time! Whoops, McCoy’s gone through it, where is he now? 1930! Okay, Kirk and Spock go after him, and what do they find? — And so on. The love-and-death tragic plot doesn’t kick in until fairly late; the ground’s been well-laid. All the exploration and adventure doesn’t distract from the tragic momentum of the second half of the story; somehow it prepares us for it, setting plots in motion that all come together at the right moment for maximum impact.

Perhaps this is a sign that the action arises more naturally out of character. But the sense of tragedy is perhaps helped along by the formal constraints of series television of that era. We know the guest star isn’t going to be added to the cast. We know we’re not going to start following an alternate future week to week. The idea of Keeler’s coming death haunts the last acts of the show; and we know it must come, because of the nature of the formula in episodic TV. Even if we haven’t seen the episode before, we’re waiting for the inevitable — again, as at any tragedy.

That developing sense of tragedy makes the not-quite-triangle of Kirk, Spock, and Keeler almost eerie. We know Kirk and Spock are close friends, and we see that through Keeler. There’s a point in the show when Keeler says that Kirk and Spock seem out of place, and Spock asks her where she thinks they would belong. “You?” she asks. “At his side. As if you’ve always been there and always will.” I found that one of those moments you sometimes get in a story that seems more powerful than can easily be explained. In formal plot terms it explains the relationship of the two men to the audience; more than co-workers, they’re friends. Still, there’s something a bit more to it. She’s said something true, and, as it happens, something that would become one of the core elements of Star Trek through all iterations of those characters. But at the same time, as the episode goes on, Spock’s the one who adheres to the implacable logic of history. He’s the incarnation of inevitability, of historical necessity. He’s the angel of death, urging Kirk to see Keeler dead. Kirk’s caught between the woman he loves and his best friend, but not quite in a way anyone else ever has been.

That developing sense of tragedy makes the not-quite-triangle of Kirk, Spock, and Keeler almost eerie. We know Kirk and Spock are close friends, and we see that through Keeler. There’s a point in the show when Keeler says that Kirk and Spock seem out of place, and Spock asks her where she thinks they would belong. “You?” she asks. “At his side. As if you’ve always been there and always will.” I found that one of those moments you sometimes get in a story that seems more powerful than can easily be explained. In formal plot terms it explains the relationship of the two men to the audience; more than co-workers, they’re friends. Still, there’s something a bit more to it. She’s said something true, and, as it happens, something that would become one of the core elements of Star Trek through all iterations of those characters. But at the same time, as the episode goes on, Spock’s the one who adheres to the implacable logic of history. He’s the incarnation of inevitability, of historical necessity. He’s the angel of death, urging Kirk to see Keeler dead. Kirk’s caught between the woman he loves and his best friend, but not quite in a way anyone else ever has been.

I’ll come back to the comparison with “The Cold Equations” in a moment, but first I want to step back to look at this episode in the larger context of Trek as a whole, or at least of this crew as a whole. I think the episode gains some poignancy from that context, and would have even at first airing: it was made late in the first season, and by that point viewers would have already seen time-travel in the show (in the episode “Tomorrow is Yesterday”) and the care that had to be taken to avoid changing the future. On the other hand, viewers would also have seen “Space Seed,” which makes for an interesting inconsistency. Spock tells Kirk Keeler brings about a Nazi victory in World War Two. But we know that World War Three will take place in the 1990s, thanks to “Space Seed.” So in theory, finding that Keeler brings a Nazi victory in World War Two, and given that from the future’s perspective all these people are long-dead anyway, Kirk should be asking: well, in the long run, is that change better or worse?

(An unthinkable question, but we will later find out that at least one Starfleet officer has actually come to idealise the Nazi regime. I always thought that was one of the most genuinely, chillingly science-fictional conceits in the whole show — that after a couple hundred years, even the most obvious evil will not just be doubted, but will become almost an academic dispute, the subject of a few specialists in history with chips on their shoulders. At any rate, Kirk doesn’t doubt the Nazi victory’s a bad thing; as I said, the show’s haunted by World War Two, and Nazis here are a reasonable shorthand for saying “the future’s gone to hell.”)

(An unthinkable question, but we will later find out that at least one Starfleet officer has actually come to idealise the Nazi regime. I always thought that was one of the most genuinely, chillingly science-fictional conceits in the whole show — that after a couple hundred years, even the most obvious evil will not just be doubted, but will become almost an academic dispute, the subject of a few specialists in history with chips on their shoulders. At any rate, Kirk doesn’t doubt the Nazi victory’s a bad thing; as I said, the show’s haunted by World War Two, and Nazis here are a reasonable shorthand for saying “the future’s gone to hell.”)

At any rate, what I think may be most interesting is what the story does for Kirk’s character, and how it sits with the way that character later developed. To start with, given Kirk’s later sterotype as a Lothario, it’s interesting to note that the first season mostly lacked romances between Kirk and the guest stars (if you want an attempt at a list of Kirk’s affairs, you can find a discussion here; most, you’ll note, were from later seasons). So having him fall in love with Keeler had real impact. And it suggests that you could look at his more casual relationships in later seasons as a result of the emotional impact of Keeler’s death.

Maybe more dramatically, though, “The City on the Edge of Forever” is a really dramatic contrast to what we learn about Kirk in Star Trek II. That Kirk, after all, doesn’t believe in the no-win scenario. And he hates to lose. Is this the same character? Or was he affected that deeply by the events of this episode? We later learn that Kirk cheated on a test specifically designed to see how one deals with death. How does that character fit with what we see here? Could it be that an element of his personality that was always present became exaggerated following this episode?

Maybe more dramatically, though, “The City on the Edge of Forever” is a really dramatic contrast to what we learn about Kirk in Star Trek II. That Kirk, after all, doesn’t believe in the no-win scenario. And he hates to lose. Is this the same character? Or was he affected that deeply by the events of this episode? We later learn that Kirk cheated on a test specifically designed to see how one deals with death. How does that character fit with what we see here? Could it be that an element of his personality that was always present became exaggerated following this episode?

Either way, if the Kirk of Star Trek II refuses to face the no-win scenario, Spock, famously, faces it straight-on. Here the man who was the figure of remorseless death in “City” faces his own ineluctable logic, and sacrifices himself. The climactic scene of that movie is, in the end, perhaps the best example of “The Cold Equations” done right, with the entire film building to that point, both in plot and theme. One man, acting on his own, faces what has to be done directly, and does it. The point that comes out there, I think, perhaps more than in “City,” and definitely more than in “The Cold Equations,” is this: there really is no such thing as a no-win scenario, because if one goes to one’s fate with determination and composure, that in itself is a win. Sacrifice transcends loss.

It’s a point less clear in the episode than might at first appear. Kirk’s choice is not actually quite as inevitable as it seems to want to suggest. The show seems to imply that Kirk faces a binary choice: Keeler lives, and the future dies, or she dies and the future lives. But that isn’t really the case. In theory she could live, and the three Starfleet officers could live on in the past with her. Since they know what will happen in the years immediately coming, they’d know not to let the Nazis win World War Two. You could imagine them trying to bring about a golden age, ‘inventing’ new technologies and new medicines well ahead of time. Does this sound manipulative? Bear in mind that later seasons of the show would introduce us to any number of Starfleet officers manipulating ‘primitive’ societies, directing them along whatever parallel they wish. You can imagine Kirk dying a little inside every time he sees this, knowing he could have done the same thing, and instead walked away.

It’s a point less clear in the episode than might at first appear. Kirk’s choice is not actually quite as inevitable as it seems to want to suggest. The show seems to imply that Kirk faces a binary choice: Keeler lives, and the future dies, or she dies and the future lives. But that isn’t really the case. In theory she could live, and the three Starfleet officers could live on in the past with her. Since they know what will happen in the years immediately coming, they’d know not to let the Nazis win World War Two. You could imagine them trying to bring about a golden age, ‘inventing’ new technologies and new medicines well ahead of time. Does this sound manipulative? Bear in mind that later seasons of the show would introduce us to any number of Starfleet officers manipulating ‘primitive’ societies, directing them along whatever parallel they wish. You can imagine Kirk dying a little inside every time he sees this, knowing he could have done the same thing, and instead walked away.

Appropriately, the final image of “The City on the Edge of Forever” is the Guardian of Forever, not the crew of the Enterprise. The Guardian, which seems to promise all sorts of further adventure and mystery. Who created it? What is the city all about it? We don’t find out. But at the end everything’s been restored, time become a perfect round figure like the Guardian itself. like fate, perhaps. All is as it was. Except that we might have learned something. Learned just that much more about the problems that can be caused by a single well-meaning time-travelling doctor, to start with. But, more seriously, I think the episode has something to say about sacrifice; a little more than “The Cold Equations” has to say. I think there is humanism, is empathy, even in tragedy. Without empathy, what point tragedy? The prose story’s empathy is equivocal, conditional. The television episode is that much braver: it understands a death is always tragic, whatever the reasons behind it, however inevitable. Because, after all, in the long run death is always inevitable. It’s only a question of how we face what must, in time, come to us all.

Matthew David Surridge is the author of “The Word of Azrael,” from Black Gate 14. His ongoing web serial is The Fell Gard Codices. You can find him on Facebook, or follow his Twitter account, Fell_Gard.

[…] on to write about the Trek episode and make a fuller comparison (edit to add: time having passed, you can find the post here). First up, though: “The Cold […]

“The show seems to imply that Kirk faces a binary choice: Keeler lives, and the future dies, or she dies and the future lives. But that isn’t really the case. In theory she could live, and the three Starfleet officers could live on in the past with her.”

An excellent article, Matthew. While this statement may be technically correct, it is simply not true to Kirk’s nature. He places his crew and his ship above ALL things. If he saves Keeler, then he has likely destroyed his ship, and his crew, even if there is some remote hope that they can effect things in the past so that the Star Trek future still comes to pass.

I do think it may be a mistake to think of the Kirk of Star Trek II as the same character as the Kirk in the original series. There are similarities, surely, and he’s played by the same actor (obviously). But the writing in the first season and the strongest episodes of the second season are in truth different animal from all that followed.

The script writers came from a generation that had lived through or even served in World War II. The problems they have their characters face are so much more powerful and real and realized than what later versions of these characters face.

No one has ever tackled this better than Torie Atkinson in her wrap-up to watching season 1 of the original Star Trek for the first time:http://www.theviewscreen.com/season-1-wrap-up/

You’re absolutely right about Kirk’s nature. What I wanted to say was that there was, in theory, a third way to go; but the fact that Kirk didn’t even consider it could be in itself a demonstration of how much he valued his ship and crew. I don’t know if it had ever been so clearly shown before how high a value he put on those things. Certainly this episode establishes it.

And I think you’re right again about how the experience of World War Two affected the writers. Like I say, the shadow of the war is there in so many episodes. And I guess it follows that a different generation of writers, with different concerns, can’t help but write characters differently. It’s something I’ve wanted to try to look at, the way ‘franchise’ characters get treated as a unity when they’re actually weird composites, but I haven’t quite found the right way into the topic. Maybe in another Marvel Comics post …

For all the talk of Kirk as a gung-ho guy going in with phasers blasting, violent action is almost never his first instinct, and when it is, he learns that he is wrong. When Kirk must take violent action, it is necessary to protect his crew, or the federation, or even humanity, and it something he approaches very, very seriously, with regret. He’s never gleeful about dealing death, as reboot Kirk and Spock were at the end of reboot Star Trek movie 1.

And I think that’s because the original writers — and many of the actors — had a better understanding of sacrifice and service. Death, even the death of an enemy, wasn’t something to be celebrated. A LOT of those episodes actually end fairly bleakly, with the Enterprise sailing away as a lonely dot of sanity in a mad universe, having barely escaped the fate of the others in the episode. A reminder that humanity is fragile and the choice between existence and destruction is a very fine one: “there but for the grace of God go I.”

[…] The Cold Edge of Forever, II: City […]