Appendix T

Unless one considers charts, tables, and mathematical formulas to be “illustrations,” the original edition of GDW’s science fiction roleplaying game Traveller (1977) contains only one piece of genuine artwork: namely, the portrait to the right. That portrait, by an uncredited artist, depicts Alexander Lascelles Jamison, the example character whose career is detailed in the first volume of the classic SF RPG. Like all Traveller characters, before he starts seeking his fortune among the stars, Jamison has already had a career, in this case in the merchant service, where he mustered out with his own ship and the rank of captain.

Unless one considers charts, tables, and mathematical formulas to be “illustrations,” the original edition of GDW’s science fiction roleplaying game Traveller (1977) contains only one piece of genuine artwork: namely, the portrait to the right. That portrait, by an uncredited artist, depicts Alexander Lascelles Jamison, the example character whose career is detailed in the first volume of the classic SF RPG. Like all Traveller characters, before he starts seeking his fortune among the stars, Jamison has already had a career, in this case in the merchant service, where he mustered out with his own ship and the rank of captain.

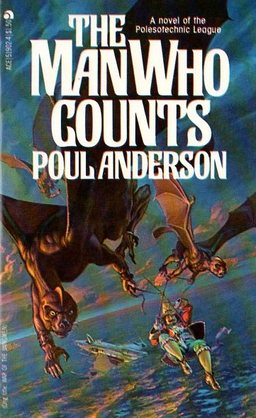

Looking at that portrait, I found myself remembering a quote from “Margin of Profit,” a story by the late Poul Anderson, first published in the September 1956 issue of Astounding Science Fiction. That story, too, depicts an interstellar merchant captain:

He was a huge man, two meters in height and broad enough to match. A triple chin and swag belly did not make him appear soft. Rings glittered on hairy fingers and bracelets on tawny wrists, under snuff-soiled lace. Small black eyes, set close to a great hook nose under a sloping forehead, peered with laser intensity.

Anderson’s merchant is, of course, Nicholas Van Rijn, president of the Solar Spice & Liquors Company, and one of the more famous characters from the period between the end of the Golden Age of Science Fiction and the rise of the New Wave.

[Click on the images in this article for larger versions.]

Unlike D&D and RuneQuest, which explicitly include appendices where their designers talk about the books and authors that inspired them as they created their respective games, Traveller includes no such appendix. I suspect that’s because Traveller, like the 1974 edition of Dungeons & Dragons, is very spare in its presentation. It consists of three 44-page volumes that paint the universe of “science fiction adventure in the far future” in very broad strokes, providing just enough rules and ideas to inspire. Also like D&D (but unlike RuneQuest), there is no setting “baked in,” leaving it to individual referees to create their own.

Unlike D&D and RuneQuest, which explicitly include appendices where their designers talk about the books and authors that inspired them as they created their respective games, Traveller includes no such appendix. I suspect that’s because Traveller, like the 1974 edition of Dungeons & Dragons, is very spare in its presentation. It consists of three 44-page volumes that paint the universe of “science fiction adventure in the far future” in very broad strokes, providing just enough rules and ideas to inspire. Also like D&D (but unlike RuneQuest), there is no setting “baked in,” leaving it to individual referees to create their own.

Of course, no act of human creation is truly ex nihilo; there are always traces of one’s own influences – and so it is with Traveller, as Alexander Lascelles Jamison makes plain. If nothing else, Marc Miller and the crew at Game Designers Workshop had read and were inspired by Poul Anderson, whose “Technic History” encompassed many short stories, novellas, and novels, spanning several thousand fictional years and providing a backdrop against which characters like Van Rijn, David Falkayn, and Dominic Flandry had their own science fiction adventures in the far future.

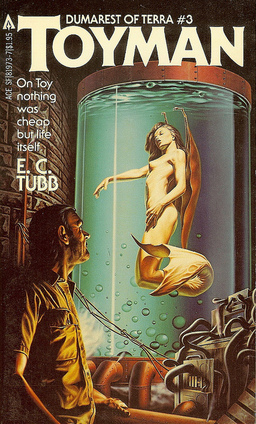

Looking further into those three little black books, you can find brief hints of other inspirational works. For example, “high,” “middle,” and “low passages” – three grades of starship travel tickets – have their origins in E.C. Tubb’s Dumarest Saga.

The real tip-offs are found elsewhere, though, in a pair of supplements produced in the first couple of years after Traveller was released. Supplement 1: 1001 Characters was released in 1978 and, as its title suggests, includes 1001 pre-generated characters. (You must remember this book was published in an era before widespread personal computer use made random generation of hundreds of characters relatively easy.)

Among those 1001 characters, nine are “drawn from the pages of science fiction” that have been “expressed in terms of Traveller characteristics.” The identities of these characters, along with eight more, are revealed in Supplement 4: Citizens of the Imperium (1979). Looking over these seventeen characters reveals a lot about the books and other media that influenced Marc Miller and others at GDW as they developed Traveller.

- John Carter of Mars, from E.R. Burroughs’s Barsoom series.

- Kimball Kinnison, from E.E. “Doc” Smith’s Lensmen series

- Jason dinAlt, from Harry Harrison’s Deathworld series

- Earl Dumarest, from E.C. Tubb’s aforementioned Dumarest Saga

- Beowulf Shaeffer, from Larry Niven’s Known Space series

- Anthony Villiers, from Alexei Panshin’s Star Well and The Thurb Revolution

- Dominic Flandry, from Poul Anderson’s Flandry series

- Kirth Girsen, from Jack Vance’s Demon Prince series

- Gully Foyle, from Alfred Bester’s The Stars, My Destination

- Luke Skywalker, from Star Wars

- James di Griz, from Harry Harrison’s Stainless Steel Rat series

- Sergeant Major Calvin, from Jerry Pournelle’s “The Mercenary” and “Sword and Scepter”

- Senior Physician Conway, from James White’s Sector General series

- Jame Retief, from Keith Laumer’s Retief series

- Simok Aratap, from Isaac Asimov’s The Stars, Like Dust

- Darth Vader, from Star Wars

- Harry Mudd, from Star Trek

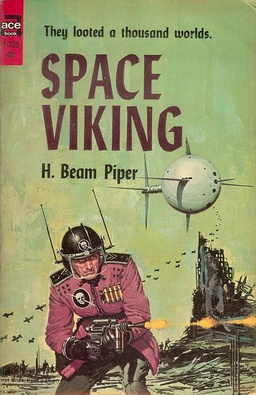

Also worth noting are references in Supplement 3: The Spinward Marches (1979) to “the Long Night” (another borrowing from Anderson) and “the Sword Worlds” (from H. Beam Piper’s Space Viking).

Also worth noting are references in Supplement 3: The Spinward Marches (1979) to “the Long Night” (another borrowing from Anderson) and “the Sword Worlds” (from H. Beam Piper’s Space Viking).

Looking over the list above, it’s worth noting that, for the most part, all of the characters come from literature or media from the 1960s or earlier. This only makes sense, given that Marc Miller was born in 1947, and thus would have been a child and teenager during the 1950s and much of the 1960s, when these works were written.

Though released in 1977, the kind of science fiction that influenced Traveller from an earlier time, just as Dungeons & Dragons reflects sensibilities born of the younger days of its creators rather than what was contemporary at the time of its release.

In a similar fashion, I would contend that Star Wars occupies a similar place in relation to Traveller than The Lord of the Rings does in relation to D&D, which is to say, a minimal and largely ex post facto influence intended to ride the coattails of a fad rather than anything more foundational. (Remember that Traveller was published just weeks after Star Wars had been released and thus it could not have exerted much influence over its design).

As a bookish kid growing up in the early 80s, when I first discovered Traveller, I found these references in the game’s supplements to be godsend. They introduced me to science fiction authors and novels I might otherwise not have encountered, just as Appendix N did for fantasy. Indeed, I fell in love with many of these authors, so much so that they have colored my own conceptions of science fiction for the last three decades – yet another positive benefit roleplaying games have had on my life and, I have little doubt, on the lives of so many others.

What great list. I was never a fan of Traveller but I liked its reference points. I was just thinking of rereading some of Anderson’s Technic League books and I’ll take this as a serendipitous prompting to dig them out.

What Fletcher said. This is a great post. An excellent bit of scholarship, James. That is both a very credible list of Traveller influences, and an attractive survey of pre-1970 SF.

Ooo. Reading list!

[…] 1978 edition of RuneQuest, and — one of my favorite gaming articles of the past year — Appendix T, in which he uses diligent detective work to brilliantly retro-fit an Appendix N for the original […]

That was a great source of information!

Any idea what Books inspired the Traveler Aliens? Aslan, K’Kree, Vargr ..?

Edmond Hamilton’s Starwolf series should be on this list.

Varnan Starwolves: Vargr

Mercenary guilds: Why was Mercenary Book 4?

Kharali/Vhollans: Humaniti seeded throughout the galaxy

Krii aliens: sounds very similar to K’kree even though different in appearance

None of those were in Traveller at the beginning.

Tolkien was clearly an influence on OD&D. Gygax underplayed it after getting in trouble for copyright violations. It’s clearly a deep and important influence.