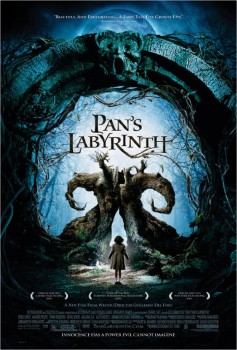

Adventures On Film: Pan’s Labyrinth

Having panned Merlin some weeks back, it’s time to dive headlong into one of the best fantasy films of this century, and possibly one of the best, period.

Having panned Merlin some weeks back, it’s time to dive headlong into one of the best fantasy films of this century, and possibly one of the best, period.

Yes, Pan’s Labyrinth (2006) is that good. Director Guillermo del Toro, he of Hellboy fame, was clearly out to prove that given solid material, sufficient devotion, and a lack of Hollywood oversight, he could deliver a contender.

True, Pan does invite several divisive questions, such as why must contemporary filmed violence be so jarringly graphic? Del Toro loves jets of blood almost as much as that eternal child-man, Quentin Tarantino, and he indulges himself more than once along his tale’s labyrinthine path. But is it necessary? Does the vivid bloodletting aid the narrative? Pan is a hybrid, true, a film about war and revolution, and such chronicles cannot easily avoid bloodshed. But as anyone who has ever seen Pan’s sewing and stitching scene can attest, this movie achieves prime “I can’t look!” status. It’s visceral; it hurts.

Pan’s Labyrinth (El Laberinto del Fauno) also begs a second question, perhaps even more sinister: is it allowable to put a child (or child character) into such peril? Pan doesn’t pull its punches. Our heroine, young Ofelia (played with no affectation whatsoever by Ivana Baquero), is in mortal danger throughout this film, and unlike, say, Harry Potter or Buffy (Slayer of the Dentally Challenged Undead), there is no guarantee she will survive.

There is a third question, most pressing of all, but I’ll get to that in a moment.

Many horror and dark fantasy magazines specifically state in their writer’s guidelines that they will not consider stories in which children are maimed, mutilated, abused, etc., and in some cases, these guidelines take an even more conservative tack, proscribing any story in which a child is at the center of a grim, potentially lethal plot.

Why, then, is such danger entirely de rigueur in the movies?

Without question, imperiled children are the norm throughout the history of story, and with (so far as I know) no cultural exceptions. The Russian girl who confronts Baba Yaga is clearly in danger, as is the African boy who ultimately slays the giant, Abiyoyo. In the non-Disneyfied versions of Aladdin (a Persian tale, with Chinese roots) and Pinnochio (Italian), the youthful heroes are frequently pushed to the limits of safety and sanity.

Sanity, of course, has some relation to the verb “to sanitize,” and that is precisely what “civilized” society has been handing consumers for at least the last hundred and fifty years. Fairy tales get dumbed down, or amusingly “fractured”; pundits explain that the original, crueler versions of the Brothers Grimm, etc., are too raw and frightening for today’s (otherwise indestructible) children.

Sanity, of course, has some relation to the verb “to sanitize,” and that is precisely what “civilized” society has been handing consumers for at least the last hundred and fifty years. Fairy tales get dumbed down, or amusingly “fractured”; pundits explain that the original, crueler versions of the Brothers Grimm, etc., are too raw and frightening for today’s (otherwise indestructible) children.

Del Toro clearly believes otherwise.

Call Pan’s Labyrinth a throwback, then, an intentional protest against the pabulum our taste-maker masters feed us. The film is a dare from moment one: stick it out, if you can, all ye intrepid, hardy film-goers. Those with a strong stomach and a curious mind will, of course, soldier on, while those with a sensitive heart will be in the gravest danger of all.

Consider the opening. We meet Ofelia and her mother as they travel by motorcade through Franco’s “revolutionary” Spain, on the way to meet with Ofelia’s new (and brutal) father, Capitan Vidal, who runs a military outpost and hunts rebels with the dedication of a Great White shark stalking prey. During a quick stop in the endless pine forests, Ofelia finds a peculiar stone in the road. After picking it up, she realizes it is a missing piece for a stumpy stone gargoyle, lost amidst the bracken.

Consider the opening. We meet Ofelia and her mother as they travel by motorcade through Franco’s “revolutionary” Spain, on the way to meet with Ofelia’s new (and brutal) father, Capitan Vidal, who runs a military outpost and hunts rebels with the dedication of a Great White shark stalking prey. During a quick stop in the endless pine forests, Ofelia finds a peculiar stone in the road. After picking it up, she realizes it is a missing piece for a stumpy stone gargoyle, lost amidst the bracken.

Nor is it just any missing piece: it is an eye. When Ofelia clicks the stone into place, she metaphorically gives eyesight to the blind, and in turn awakens the magical forces that have been lying dormant all around her. Out pops a creature, a guide, an insect. A fairy?

Whatever it is, it looks decidedly suspicious. Thus Del Toro immediately establishes one of the film’s primary themes, that of trust. Does Ofelia dare trust her mother’s decision to marry this obviously vile officer, Capitan Vidal? Can she trust the Capitan’s housemaid, Mercedes? And above all, can she trust her new friend, this clicking, shape-shifting fairy?

If the fairy seems duplicitous, inscrutable, and diabolical, just wait until it leads her into el laberinto where, in what appears to be a vast and very deep well, she meets el fauno, the faun.

This is not a C.S. Lewis faun, no, no. We are a long way from Mr. Tumnus. This faun is eight feet tall, has legs like tree trunks, and sports a decidedly demonic aspect. It promises Ofelia the world, yes, but only if she completes three tasks, none of which will be safe, and the details of both how and why remain, thanks to the shadowy faun, very sketchy.

Monsters are as monsters do, and in Pan’s Labyrinth, the notion that at least some of the monsters are human is never up for debate. But what to make of the monsters that hide in Ofelia’s labyrinth?

Perhaps they are benign, but they clearly play by their own rules, and if they are friends to Ofelia, it is not on terms she can understand.

Perhaps they are benign, but they clearly play by their own rules, and if they are friends to Ofelia, it is not on terms she can understand.

I won’t divulge any more of the plot. Never fear, significant spoilers will not here be found.

But I am forced to say this: so often in fantasy, the question with which we are left at the end is, “Was it all a dream?” In this brutal, cunning film, we must ask instead, “Was the dream a lie?”

That, my friends, is a far more devastating question.

‘Til next time.

Onward.

Mark Rigney has published three stories in the Black Gate Online Fiction library: ”The Trade,” “The Find,” and “The Keystone.” Tangent called the tales “Reminiscent of the old sword & sorcery classics… once I started reading, I couldn’t stop. I highly recommend the complete trilogy.” In other work, Rigney is the author of “The Skates,” and its haunted sequels, “Sleeping Bear,” and Check-Out Time. His website is markrigney.net.

Far too late now, but when I first saw Pan’s Labyrinth I thought that Ivana Baquero could have played a perfect Tiffany Aching (from Terry Pratchett’s Wee Free Men books).

I don’t think Del Toro made Pan’s Labyrinth for children. You know the conventional wisdom about protagonists’s ages: children and teens want to read about main characters about two years older than themselves, and will reject stories about characters their own age or younger. Hence, says Orson Scott Card, the audience for a non-picture-book story about a seven year old is an adult audience. (There’s plenty I disagree with OSC about, but when he talks craft and business, I allow for the possibility I’ll learn something.)

Until about age 7, most kids are not reliably able to tell the difference between reality and imagination. It’s part of the puzzle of Pan’s Labyrinth that Ofelia is right on that edge. And that edge is precisely why it would be unwise for parents to allow a child Ofelia’s age or younger to watch that film.

Yes, good lord this is as far from a children’s movie as you can get, to the extent that it was actually (and deservedly) rated R. But it’s beautiful and magical and occasionally terrifying and heartbreaking.

Joe – I don’t know the Wee Free Men books, but I’ll try to check those out. Not Discworld, I take it? And yes: it is most certainly rated R.

Sarah – I certainly didn’t mean to imply the film is for kids. It’s not. I’m not even sure they’d have much interest. One can only imagine the questions: “Why are those men hiding in the woods?” “Why are these other men so mean?”

If I remember correctly, Del Toro wrote the role of Ofelia for a seven-year-old, then adjusted it upward once Baquero auditioned. While I have always had my suspicions about the seven-year reality threshold, you may well be onto something regarding the director’s overall design.

Thank you both for your thoughts!

The Wee Free Men books are set on Discworld but they’re not part of the mainline series — they’re a separate YA series about a 10(?) year old girl, Tiffany Aching, who discovers she’s a witch. Some of our favorite Discworld witches do show up in the series. Highly, highly recommend.

And as I think back to when Pan’s Labyrinth was in theaters, I think there was a certain amount of confusion as to whether it was a children’s movie or not, just based on the previews and the marketing campaign.

I think some of the marketing confusion must have stemmed from the fairy tale aspect taking such a big role alongside and often reflecting the harsher and more adult themes. In more than one of his films Del Toro places children and their inherent innocence at the center of these dark, very mature stories and in Pan’s Labyrinth he does so to gut wrenching effect. A truly great film.

[…] Adventures On Film: Pan’s Labyrinth (2013) […]

[…] Or, for an example of a film I deeply love (and fear), there’s this review, of Pan’s Labyrinth. […]