The Gestation of Cape and Cowl: Thoughts On Jess Nevins’ The Evolution Of The Costumed Avenger

Though he’s written short stories and three self-published novels, Jess Nevins is likely best known as an excavator of fantastic fictions past: an archaeologist digging through the strata of the prose of bygone years, unearthing now pieces of story and now blackened ashes of some once-thriving genre long since consumed and built over by its lineal successor. Across annotated guides (three to Alan Moore and Kevin O’Neill’s League of Extraordinary Gentlemen, one to Bill Willingham and Mark Buckingham’s Fables) and self-published encyclopedias (of Pulps and of Golden Age Superheroes with Pulp Heroes soon to come, as well as 2005’s Monkeybrain-published Encyclopedia of Fantastic Victoriana) Nevins has reassembled old pieces of fantastika, indicating direct influences on modern writing and establishing directories of almost-forgotten story. He’s one of the people broadening the history of genre, in his books, and in articles such as his pieces for io9 on the Victorian Hugo Awards that never were.

Though he’s written short stories and three self-published novels, Jess Nevins is likely best known as an excavator of fantastic fictions past: an archaeologist digging through the strata of the prose of bygone years, unearthing now pieces of story and now blackened ashes of some once-thriving genre long since consumed and built over by its lineal successor. Across annotated guides (three to Alan Moore and Kevin O’Neill’s League of Extraordinary Gentlemen, one to Bill Willingham and Mark Buckingham’s Fables) and self-published encyclopedias (of Pulps and of Golden Age Superheroes with Pulp Heroes soon to come, as well as 2005’s Monkeybrain-published Encyclopedia of Fantastic Victoriana) Nevins has reassembled old pieces of fantastika, indicating direct influences on modern writing and establishing directories of almost-forgotten story. He’s one of the people broadening the history of genre, in his books, and in articles such as his pieces for io9 on the Victorian Hugo Awards that never were.

Now he has a new book about the development of the superhero and what came before. The Evolution of the Costumed Avenger is subtitled The 4000–Year History of the Superhero, and delivers what it promises. Much that has fallen into obscurity is brought to light in this book. Precedents are unearthed. Archetypal forms are catalogued. But more than that, and perhaps more valuable, known things are recontextualised. Four thousand years of the Western heroic tradition, if not of Western literary tradition, are here imagined in a new way: as prologue to the coming of the superhero. The superhero, lately so central to popular fiction on page and screen, here finds a new apotheosis as the lens through which all preceding heroes are to be perceived. As the end-point of evolution.

And that’s fair enough. That’s what a history often does, foregrounding its subject, putting it at the centre of things. Nevins does his job well, writing in a style that’s academic in its rigour and its careful references to other scholars, while avoiding the jargon and convoluted syntax that mars much academic writing. His prose is clear, yet dense with information, moving quickly while constantly introducing new facts and new ideas. Given the vastness of his subject the book’s quite brief and indeed perhaps too brief: barely 300 pages, though those (like me) who relish discursive and tangential footnotes will appreciate the further 50 pages of endnotes. Nevins’ research is excellent throughout, particularly in the chapters covering the last two or three centuries. As is perhaps inevitable I have some questions and some doubts; most of them revolve around the way that Nevins defines the book in its opening chapter, and around the concluding chapters where Nevins presents a brief history of post–Golden Age superheroes. But The Evolution of the Costumed Avenger is clearly a success, not just an entertaining book but one vital for its field; a work that provides much food for thought to any reader with an even marginal interest in its subject.

(The measure of the book’s success is that the temptation’s irresistible to delve into it more deeply, to consider the arguments Nevins puts forward. The problem is that doing so means focussing on points of disagreement and debatable statements, even though there’s much more to the book than those points and statements. So I want to make it clear that if in what follows I seem to be overly concerned with doubts, that’s actually a sign of how well the book does what it does — it encourages further discussion, and challenges readers to consider how they think about superheroes and regular heroes.)

(The measure of the book’s success is that the temptation’s irresistible to delve into it more deeply, to consider the arguments Nevins puts forward. The problem is that doing so means focussing on points of disagreement and debatable statements, even though there’s much more to the book than those points and statements. So I want to make it clear that if in what follows I seem to be overly concerned with doubts, that’s actually a sign of how well the book does what it does — it encourages further discussion, and challenges readers to consider how they think about superheroes and regular heroes.)

The troubles I find in the book’s self-definition may be a function of the inherent difficulties in defining the nature of the superhero. Nevins mounts a strong argument for genres as fuzzy-edged ideas, and as “the superhero” as a particularly fuzzy example of a genre. Rather than make hard-and-fast rules about what is or is not a superhero, Nevins (to an extent following the lead of Kurt Busiek) suggests that characters have elements that contribute to a sense of superheroness — things like “a dual identity,” “a code name,” “a heroic mission,” and so on. If the character has enough of these elements as part of their essence, their heroenkonzept, then they’re a superhero. Before 1938, you’re likely to find characters with some of those important elements but not enough to make them full-fledged superheroes; Nevins calls these characters protosuperheroes, characters existing somewhere on the superhero continuum but not quite fitting the typical idea of a superhero proper. The book, then, examines the development of protosuperheroes over time, as more and more of these elements accrete, until finally the true superhero emerges. As Nevins puts it in his Introduction, the book’s “tracing the history of … the ‘protosuperhero,’and how the varieties of that character influenced (from a greater or lesser remove, and to a greater or lesser degree) the superhero.”

It does this within mostly well-chosen limits. Nevins is less interested in long lineage chains (this character influenced this one that shaped this protosuperhero that led to these superheroes) than he is in direct ancestors of the superhero. Technically, given the fuzziness of genre definition, virtually any character could be said to have some elements of the superhero, meaning any character could be construed, however tenuously, as a protosuperhero. But Nevins keeps his end-point in mind and does a good job of focussing on characters who most clearly foreshadow the true superhero. This does create a chronological imbalance, though, since characters closer in time to the emergence of superheroes are likely to look more like them. As a result, some of the early chapters cover vast swathes of time, and don’t develop a sense of continuity — protosuperheroes seem to be isolated examples, rather than parts of a developing tradition that speaks from work to work over the years. That changes notably once Nevins reaches the late eighteenth century or thereabouts, when he finds many more characters to work with and is able to start tracing clear continuities.

It does this within mostly well-chosen limits. Nevins is less interested in long lineage chains (this character influenced this one that shaped this protosuperhero that led to these superheroes) than he is in direct ancestors of the superhero. Technically, given the fuzziness of genre definition, virtually any character could be said to have some elements of the superhero, meaning any character could be construed, however tenuously, as a protosuperhero. But Nevins keeps his end-point in mind and does a good job of focussing on characters who most clearly foreshadow the true superhero. This does create a chronological imbalance, though, since characters closer in time to the emergence of superheroes are likely to look more like them. As a result, some of the early chapters cover vast swathes of time, and don’t develop a sense of continuity — protosuperheroes seem to be isolated examples, rather than parts of a developing tradition that speaks from work to work over the years. That changes notably once Nevins reaches the late eighteenth century or thereabouts, when he finds many more characters to work with and is able to start tracing clear continuities.

More seriously, if the book is on the whole an excellent analysis of the development of the superhero and protosuperhero in the Anglo-American tradition, including the broader Western tradition out of which English and English literature developed, I think Nevins oversteps himself by arguing (on page 14) that that’s the only protosuperheroic tradition that influenced the superhero. It’s hard to see the Thousand Nights and a Night not having an influence on superhero fiction, for example, and generally there’s been much written over the years about the influence of Arabian literature on Medieval European romance (thus by extension on the superhero). I’d disagree with Nevins when he says that “the heroes of Chinese wuxia fiction …aren’t relevant to the history of the superhero.” As I see it, wuxia fiction gave rise to the Shaw Brothers and Bruce Lee, which gave rise to Shang-Chi and Iron Fist and Richard Dragon and Bronze Tiger — a superheroic tradition. So one must wonder what exactly the history of the superhero is. Are some superheroes more central than others? Or are there multiple traditions within the overall history of the superhero? For example, if Nevins’ protosuperhoic family tree provides the ancestry of the tradition of Superman and Spider-Man, is it possible to see a connected-but-different superhero tradition developing around works and characters like Astro Boy, Princess Knight, Science Ninja Team Gatchaman, Sailor Moon, Project A-ko, and Strayer’s Chronicle — and, if so, are its ancestors different from the Western one?

It’s perfectly fair to say that these questions are beyond the scope of the book; my problem is that Nevins doesn’t say that. Instead, he makes the broader claim that the protosuperheroes he writes about constitute the only tradition relevant to the development of the superhero, with the implicit claim that there’s only one tradition of superheroes as well. He does provide a fascinating appendix listing protosuperheroes from outside the West, so this is not a failure of knowledge. And he consistently points out superheroes and protosuperheroes who were members of, or were created by, marginalised groups within the West; so neither is this gap for lack of thinking about the subject. I think this is, more simply, an issue with how the matter of the book is framed.

It’s perfectly fair to say that these questions are beyond the scope of the book; my problem is that Nevins doesn’t say that. Instead, he makes the broader claim that the protosuperheroes he writes about constitute the only tradition relevant to the development of the superhero, with the implicit claim that there’s only one tradition of superheroes as well. He does provide a fascinating appendix listing protosuperheroes from outside the West, so this is not a failure of knowledge. And he consistently points out superheroes and protosuperheroes who were members of, or were created by, marginalised groups within the West; so neither is this gap for lack of thinking about the subject. I think this is, more simply, an issue with how the matter of the book is framed.

Consider also Nevins’ last three chapters, which (in order) looks closely at the development of comics and comic superheroes through 1941, then considers superheroes in comics from there to the present, and finally discusses the history of superheroes on film. There are some wonderful observations in these chapters, which are never less than readable. But they don’t seem to me to link up to the preceding discussion of protosuperheroes. Character elements from the protosuperheroes recur in the superheroes, yes, but the idea of a logical progression doesn’t emerge. It feels more like an evolutionary leap: as though superheroes, when they appear, do so in a burst of creativity that forces such rapid evolution in such a short time that they become something entirely different from their predecessors. Although we’ve seen the protosuperheroes slowly evolve to the point where the superhero developed, and that story is clear and coherent, the story of the superhero and how the superhero was shaped over time doesn’t seem defined by protosuperheroes — or even that directly linked to them.

In fact, I can’t help but wonder what happened to protosuperheroes after the superhero emerged. Was there any difference in the way heroes were conceived once the superhero had been created? Nevins chooses not to deal on the interrelations between superheroes and post-1938 protosuperheroes, and that’s an entirely understandable choice given the limitations of page count. Still, it can’t help but feel like an omission after everything we’ve had up to that point, like a story thread dropped.

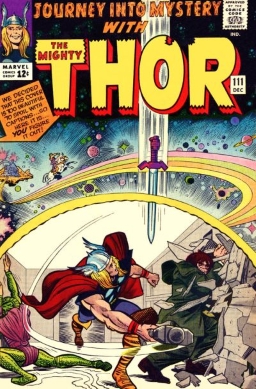

I will say in passing that those last chapters have a few other issues to my eyes. First, there’s not much discussion of superheroes outside of Marvel, DC, or Image, and other than a brief mention of the Wild Cards series nothing about superheroes in prose. Second, I think his division of superhero history into various ages is overdetermined — at some points he looks for a new age to begin around a given year simply because the ages of comics history usually run for a certain length — and I’d question his aesthetic evaluation of some of the ages. In particular, I don’t think the Bronze Age (which he defines as running from about 1970 to about 1984) was as creatively poor as he suggests. It had a higher miss-to-hit ratio than the Silver Age, particularly than the Silver Age Marvels, but then one might say the same of every age of comics. Thirdly, I didn’t feel his discussion of film superheroes was well-integrated into his overall discussion of superhero evolution; and some of his assessments of individual movies struck me as debatable in a way that tends to simplify the story of superheroes on film. (I think he underrates The Crow and at least the first two Blade movies, which to my mind really sparked the super-hero movie renaissance; I think he overrates The Incredibles, though I’m clearly in the minority there; and I’m not comfortable with his argument that Sam Raimi’s Spider-Man provided “sudden, undeniable evidence to the movie industry that super-hero films could not just be profitable, but could function as tent-pole films,” as I’d say Tim Burton’s Batman did the same thirteen years before.)

I will say in passing that those last chapters have a few other issues to my eyes. First, there’s not much discussion of superheroes outside of Marvel, DC, or Image, and other than a brief mention of the Wild Cards series nothing about superheroes in prose. Second, I think his division of superhero history into various ages is overdetermined — at some points he looks for a new age to begin around a given year simply because the ages of comics history usually run for a certain length — and I’d question his aesthetic evaluation of some of the ages. In particular, I don’t think the Bronze Age (which he defines as running from about 1970 to about 1984) was as creatively poor as he suggests. It had a higher miss-to-hit ratio than the Silver Age, particularly than the Silver Age Marvels, but then one might say the same of every age of comics. Thirdly, I didn’t feel his discussion of film superheroes was well-integrated into his overall discussion of superhero evolution; and some of his assessments of individual movies struck me as debatable in a way that tends to simplify the story of superheroes on film. (I think he underrates The Crow and at least the first two Blade movies, which to my mind really sparked the super-hero movie renaissance; I think he overrates The Incredibles, though I’m clearly in the minority there; and I’m not comfortable with his argument that Sam Raimi’s Spider-Man provided “sudden, undeniable evidence to the movie industry that super-hero films could not just be profitable, but could function as tent-pole films,” as I’d say Tim Burton’s Batman did the same thirteen years before.)

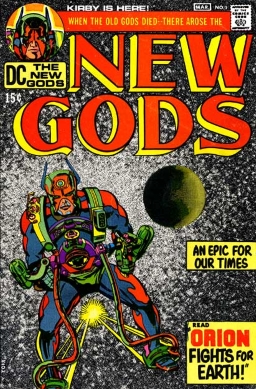

I suspect many of the questions I’m left with about the book might have been cleared up if Nevins had listed a few of the characters he considers central to the superhero tradition (or traditions), outlined some of what made them central, and showed how those aspects are connected to their protosuperheroic origins and how they changed across the course of superhero history. With respect to what makes a character central to superhero tradition, how much does commercial success matter, and how much artistic success, and how much influence on later creators? Given that characters like Superman and Batman and Wonder Woman are important, given that Spider-Man is important — how central are the Fantastic Four? Or the Goodwin/Simonson Manhunter? Are Alan Moore’s superhero stories central to the tradition, or parodies undermining it? Personally, when I think of superheroes, I reflexively think of Jack Kirby’s work, with the Fourth World characters as the purest distillation of the idea of the superhero. I’m not sure Nevins does, which is fine; but I’m not sure who he does think of as essential.

I note that as Nevins works his way through protosuperheroes from antiquity through the Middle Ages, he dismisses certain characters as protosuperheroes based on criteria I’m not sure I agree with, and indeed criteria I’m not sure are entirely fair. In particular, he views the possession of a selfless sense of mission as central to a superhero, which is logical on the surface. But what is selflessness? For Nevins, characters in antiquity who try to claim a throne due them by inheritance aren’t selfless, nor are characters in the Middle Ages who depart on a holy war. But is that fair? If you believe in kingship, isn’t establishing a rightful ruler an act benefiting the community, and thus in part selfless? If you hold the beliefs of a medieval Christian, isn’t going on Crusade a selfless act, putting yourself at risk for the sake of God and hence of goodness? That is, isn’t selflessness something that varies according to cultural norms?

I note that as Nevins works his way through protosuperheroes from antiquity through the Middle Ages, he dismisses certain characters as protosuperheroes based on criteria I’m not sure I agree with, and indeed criteria I’m not sure are entirely fair. In particular, he views the possession of a selfless sense of mission as central to a superhero, which is logical on the surface. But what is selflessness? For Nevins, characters in antiquity who try to claim a throne due them by inheritance aren’t selfless, nor are characters in the Middle Ages who depart on a holy war. But is that fair? If you believe in kingship, isn’t establishing a rightful ruler an act benefiting the community, and thus in part selfless? If you hold the beliefs of a medieval Christian, isn’t going on Crusade a selfless act, putting yourself at risk for the sake of God and hence of goodness? That is, isn’t selflessness something that varies according to cultural norms?

Consider a few examples. Nevins dismisses Cadmus as simply following the orders of the oracle of Delphi; but how many Silver Age X-Men stories had the team following the orders of Professor X, or Suicide Squad stories had the team following the orders of Amanda Waller? The winged Daedalus is discounted because he’s simply seeking escape — but I’d argue that the story of Daedalus is the story of a great artificer, who, imprisoned by an enemy, uses his technological cunning to build a powerful outfit to save himself. In other words, Daedalus is Tony Stark. (One might consider also Wayland Smith, not mentioned by Nevins, in which the parallels are even closer.)

Nor am I convinced by Nevins’ dismissal of Aeneas as a protosuperhero. It is true, as he says, that the piousness of Aeneas doesn’t really emerge as a strong theme in most superhero characters. But to say that Aeneas has no heroic mission, as Nevins also does, assumes that the commands given him by the gods have no moral dimension. It also, to me, doesn’t deal with the passage where Aeneas is told by his father’s shade that “tu regere imperio populos, Romane, memento; / hae tibi erunt artes; pacisque imponere morem, / parcere subiectis, et debellare superbos” — translated by Jane Mason here as “You, O Roman, govern the nations with your power — remember this! / These will be your arts – to impose the ways of peace, / To show mercy to the conquered and to subdue the proud.” It’s a nationalistic statement, yes, but one that articulates an idea of disinterested justice as a guide for Aeneas. I’m a little surprised Nevins ignores it in discussing the evolution of the protosuperhero; if Aeneas is unlike a superhero in many other ways, this moment seems a fairly direct predecessor of later heroes’ sense of heroic mission.

It’s an ideal whose imperialism is at odds with most modern ideals of heroism, certainly. But any hero-story aiming at speaking to its culture must speak to the ideals of heroism in its culture, usually by celebrating them. If you think that the modern concept of heroism is necessary to the superhero, or the protosuperhero, then there’s not much point in looking for precedents in characters from societies that had a different concept of heroism. I don’t think Nevins thinks this, necessarily; he convincingly points to the semilegendary character of Nectanebo II as a direct influence on the modern superhero wizard. But then is Aeneas not a direct influence on the archetype of the patriot superhero, so influential in the Golden Age? (Note that Nevins does consider Aeneas as being, like Lot or Ut-Napishtim, an example of the “one just man” archetype, sole survivor of a worldwide devastation; for Nevins this is not properly superheroic, being a passive characteristic, but it’s hard not to notice that it’s also an archetype present in a host of superheroes from Superman through the Miles Morales Spider-Man.)

It’s an ideal whose imperialism is at odds with most modern ideals of heroism, certainly. But any hero-story aiming at speaking to its culture must speak to the ideals of heroism in its culture, usually by celebrating them. If you think that the modern concept of heroism is necessary to the superhero, or the protosuperhero, then there’s not much point in looking for precedents in characters from societies that had a different concept of heroism. I don’t think Nevins thinks this, necessarily; he convincingly points to the semilegendary character of Nectanebo II as a direct influence on the modern superhero wizard. But then is Aeneas not a direct influence on the archetype of the patriot superhero, so influential in the Golden Age? (Note that Nevins does consider Aeneas as being, like Lot or Ut-Napishtim, an example of the “one just man” archetype, sole survivor of a worldwide devastation; for Nevins this is not properly superheroic, being a passive characteristic, but it’s hard not to notice that it’s also an archetype present in a host of superheroes from Superman through the Miles Morales Spider-Man.)

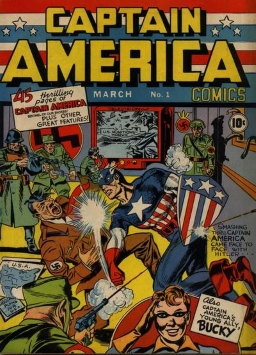

Nevins in fact links patriot heroes to an even earlier figure, Samson; but then dismisses Samson as a protosuperhero because his mission was not heroic to the Philistines. That is, Samson’s actions were only heroic from a certain point of view. For Nevins, “war heroes” who “fail the viewpoint test” don’t have a proper sense of heroic mission, although Golden Age superhero characters like Captain America “have other elements of the superhero scale to make up for it.” Personally, I read those characters a little differently. Of course Samson or the World War Two Captain America acted to help one nation in combat with another. But I don’t think that action can be distinguished from acting out of a sense of moral rightness. That is, I’d say those stories were told in part to show that goodness was with one nation and not the other. I don’t think there’s the clear division of motives Nevins implies.

In fact, when it comes to heroes embodying goodness, there’s a curious omission in the book’s chronology. Nevins doesn’t mention Christ as a protosuperhero, even though that’s a character who clearly has several of the superheroic elements he mentions — among them not just a sense of mission, but also an unusual origin story, superpowers, extraordinary skills and abilities (in public speaking if nothing else), extraordinary opponents (Satan et al), an aversion to killing, a distinctive appearance (in later iconography), a code name (“Christ,” a title meaning “anointed one”) and so on and so forth. The harrowing of hell even adds an action element, while the partial retcon of Paradise Lost adds a scene of Christ in a special car (the “chariot of paternal deity”) going into a fight scene against devils. Why not consider him?

(Certainly Nevins is exhaustive otherwise. There are some minor omissions, of course. He chooses not to examine fairy tales, for example, while Byron’s Manfred is left out of an otherwise exhaustive and admirable look at the development of the sorcerer-hero image, and Sherlock Holmes is mentioned without being given any deep consideration as a protosuperhero in his own right. And, as English and English literature develops, Nevins turns away from European chivalric romances that were not translated into English — Nevins mentions Aiol, Girart de Roussillon, and the Swan Knight, to which one might add Dietrich of Bern. I’m a little skeptical of that choice, given that at that time England was ruled by French-speakers and its court life dominated by the French language. Is it appropriate, then, to divide these characters from Charlemagne and the Arthurian characters? Or were they all part of the general European development of the chivalric romance, which later gave rise to Orlando Furioso and The Faerie Queene? There may be a case for excluding them, but I would have liked to see it articulated. All these omissions, though, strike me as essentially matters of taste and emphasis. The thrust of the arguments Nevins make don’t require them.)

(Certainly Nevins is exhaustive otherwise. There are some minor omissions, of course. He chooses not to examine fairy tales, for example, while Byron’s Manfred is left out of an otherwise exhaustive and admirable look at the development of the sorcerer-hero image, and Sherlock Holmes is mentioned without being given any deep consideration as a protosuperhero in his own right. And, as English and English literature develops, Nevins turns away from European chivalric romances that were not translated into English — Nevins mentions Aiol, Girart de Roussillon, and the Swan Knight, to which one might add Dietrich of Bern. I’m a little skeptical of that choice, given that at that time England was ruled by French-speakers and its court life dominated by the French language. Is it appropriate, then, to divide these characters from Charlemagne and the Arthurian characters? Or were they all part of the general European development of the chivalric romance, which later gave rise to Orlando Furioso and The Faerie Queene? There may be a case for excluding them, but I would have liked to see it articulated. All these omissions, though, strike me as essentially matters of taste and emphasis. The thrust of the arguments Nevins make don’t require them.)

Perhaps Nevins chooses not to consider Christ as a protosuperhero because he’s a god. Nevins argues that gods can’t count as superheroes because they by necessity lack an element of finality and “don’t risk anything by their actions.” I’d disagree, for at least three reasons. First, many gods — like Christ, like Horus, like the Norse deities — do in fact die. Second, death is not the only possible risk for a character; the eternal torture of Prometheus seems a fate as bad or worse than death, if indeed not simply a stand-in for the torments of Hades. Thirdly, various gods are in fact superheroes: Hercules and Thor perhaps most notable, but Kirby’s New Gods are explicit attempts to make super-hero gods.

One might argue that the Marvel Comics versions of Hercules and Thor have rather less to do with their mythic originals than, say, Milton’s Christ does to the Christ of the gospels. But Nevins typically writes about characters, not stories, not individual tellings of stories, and not specific readings of specific tellings. He does consider the way a tradition of a character changes, but also tends to view a character as a unitary whole, a concept across time. Hector as described in Homer and Hector as described a couple thousand years later in medieval romance are discussed at the same point in the book. There’s some logic to that, as Nevins is trying to trace the influence the figure of Hector had on the development of the superhero; and, here and elsewhere, he does distinguish the way in which different versions of the character have different effects on the development of the protosuperheroic tradition, so this is not the problem it might have been. But it does seem inconsistent to tie together variants of some characters across the centuries while dismissing others, as in the case of superheroic gods.

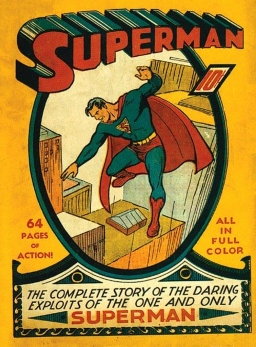

In a way, this character-centred approach stands out more in later chapters when Nevins writes about modern superheroes, so often not just collective creations but the product of different writers over time bringing different concepts to the general idea of a specific character. Nevins tends to view a character as a sum total of all the texts about that character — the product of a ‘megatext.’ That’s a useful word, and a useful concept, but the reality is occasionally less clear-cut. In an industry where retcons and continuity inserts are common, how coherent is any single character over time? Conversely, modern-day Superman is theoretically not the same character as the one that appeared in the 1940s (“the Superman of Earth-2”); but is that distinction really useful? What about characters, like Frank Miller’s Elektra or Jim Starlin’s Adam Warlock, whose adventures are intended to end but who are later revived? Is the official continuity of the character relevant in these cases?

In a way, this character-centred approach stands out more in later chapters when Nevins writes about modern superheroes, so often not just collective creations but the product of different writers over time bringing different concepts to the general idea of a specific character. Nevins tends to view a character as a sum total of all the texts about that character — the product of a ‘megatext.’ That’s a useful word, and a useful concept, but the reality is occasionally less clear-cut. In an industry where retcons and continuity inserts are common, how coherent is any single character over time? Conversely, modern-day Superman is theoretically not the same character as the one that appeared in the 1940s (“the Superman of Earth-2”); but is that distinction really useful? What about characters, like Frank Miller’s Elektra or Jim Starlin’s Adam Warlock, whose adventures are intended to end but who are later revived? Is the official continuity of the character relevant in these cases?

Nevins, apparently contradicting his argument that gods can’t be superheroes due to their lack of endings, observes that few superheroes have the sort of conclusions to their stories typical of protosuperheroes and mythic heroes. But again I’m not sure I agree. Endings are often postulated as possible futures (as in The Dark Knight Returns). Endings are introduced and then undone (as in the cases of Elektra and Adam Warlock). And some intended or possible endings are simply ignored; Steve Ditko brought his cycle of stories about Doctor Strange to a end, and the character might have ended there — but there was no reason for Marvel to stop publishing a moneymaking character, and so it didn’t. While Nevins implies that a story truly ends with final death, I’ll note that stories may in fact end in any number of ways including “they lived happily ever after.” If a story comes to an end, it comes to an end, whether the rest of a character’s life is described or not.

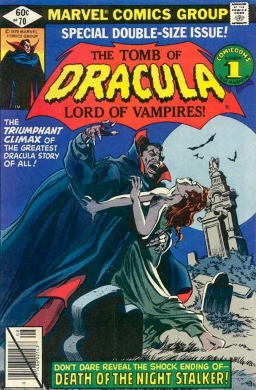

Still it has to be said that Nevins’ focus on character instead of works (or readings of works) is effective, not least because he knows when to break away from the overall history of a character to zero in on an origin or the introduction of a new aspect to the character. He adroitly uses character concepts as a way to give some unity to his sprawling early chapters. Later chapters discuss the nature of individual creations versus the collective creations of pulps and comics — while Nevins consistently goes out of his way to name the creators of the characters he examines. That’s an admirable decision, and I found at one point unintentionally helped explain his character-centred approach, when he referred to Marvel’s Tomb of Dracula as the creation of Roy Thomas and Gene Colan. That’s perfectly accurate, but Thomas wrote only the first issue and was followed by three more writers over five issues until Marv Wolfman took over the book with issue 7 and wrote it until its eventual cancellation with number 70. Thomas was the writer who created the title; Wolfman was the writer who established Marvel’s Dracula as a complex character, invented many of the supporting cast (including Blade and vampire-detective Hannibal King), and is generally the writer most associated with the book. The original writer here not only is technically not the creator of the character — that’d be Bram Stoker — but also isn’t even the writer most associated with this iteration of the character. Dealing with characters rather than individual stories gets around the question of who did what, presenting what’s relevant about the idea of a character.

Nevins’ readings of the ‘megatext’ of individual characters are always fascinating. He makes a convincing case for the centrality of pre-pulp protosuperhero Nick Carter, for example. And the overall story he tells is remarkably coherent, given the number of characters and number of years involved. He has a good eye for which characters are probable ancestors of which other ones, and which are likely to be interesting oddities that went unread — he has a feel for the likelihood of influence, for what’s part of a lineage and what’s a fascinating obscurity. He finds any number of interesting characters, such as the African-American superhero The Crimson Skull, who first appeared in a 1921 film. He points out true superheroes before Superman. And he articulates some intriguing characteristics and subtypes of the superhero; I was drawn to his discussion of heroes who are hidden kings of their cities, characters like Daredevil and Batman who have a specific relationship to their urban spaces, an encyclopedic knowledge of the shadows and back alleys they haunt.

Nevins’ readings of the ‘megatext’ of individual characters are always fascinating. He makes a convincing case for the centrality of pre-pulp protosuperhero Nick Carter, for example. And the overall story he tells is remarkably coherent, given the number of characters and number of years involved. He has a good eye for which characters are probable ancestors of which other ones, and which are likely to be interesting oddities that went unread — he has a feel for the likelihood of influence, for what’s part of a lineage and what’s a fascinating obscurity. He finds any number of interesting characters, such as the African-American superhero The Crimson Skull, who first appeared in a 1921 film. He points out true superheroes before Superman. And he articulates some intriguing characteristics and subtypes of the superhero; I was drawn to his discussion of heroes who are hidden kings of their cities, characters like Daredevil and Batman who have a specific relationship to their urban spaces, an encyclopedic knowledge of the shadows and back alleys they haunt.

In general, Nevins’ work tends to slightly de-centre the characters we think we know to be the first of something, the Pimpernels and Zorros and Supermans, pointing out predecessors and contexts. That makes it a useful corrective. Some of his specific readings are challenging, as well, as when he points out that Marvel’s Punisher is simply a serial killer (at least, I have sympathy for that reading, though I’m not convinced the character’s 1986 miniseries was “the first time in Marvel’s history” a serial killer was presented as a comic’s protagonist — Wolverine had already had a miniseries, and Tomb of Dracula would seem another example). Nevins is an intelligent, alert reader of superheroes, and is able to tell a convincing story of their origins simply by setting aside preconceptions and going through the chronology of heroic fiction with a careful eye.

I found, in the end, that one of the things he brings home in this book is the oddity, the real strangeness, of the superhero. There’s a reason it took four thousand years of recorded literary history before the superhero was invented. As Nevins points out, most super-heroes aren’t out-and-out rebels against mainstream North America. I personally find something of a revolutionary subtext in the X-Men, who explicitly act out of a belief that mutants will replace all human society; and I think characters like Thor and the New Gods who represent alternative societies (often with a kind of ontological superiority) implicitly challenge the norms of the everyday world. But set that aside. The point is, most super-heroes break the law while also seeking to uphold it. They transgress social norms in the course of upholding society. It’s a paradox that took several thousand years to emerge.

Does it represent a fundamental political incoherence? There are obvious echoes of fascism in the idea of the superhero, and Nevins takes care to point out that vigilante groups like the Ku Klux Klan are uncomfortably close to the superhero image, if only in their own minds. While he says in a note on page 319 that superhero characters “are not fascist,” in another note on page 327 he observes that there’s “something innately Fascist to superhero fiction and film, even if the superheroes … are vaguely moderate-left politically.” Still, I wonder if there isn’t also something inherently democratic in the typical superhero; or at least something in the superhero that requires democracy. The superhero is a character of remarkable gifts who does not seek to use them to rule. If they step outside some laws, they also (mostly) accept the legal process of courts and prisons. Usually, they act not out of a concern for themselves or the superpowered people around them, but out of a concern for the powerless — for the common people. They (mostly) can’t seem to change the world in which they act, in terms of changing governments or introducing meaningful new mass-produced technologies; but within that world they support law in a chaotic manner. Perhaps the best way to read the superhero is as pure narrative, but as is so often the case, the sense of meaning in a good narrative seems (to some of us, anyway) to encourage a symbolic reading of the story: to suggest hidden depths, whose articulation needs recourse to complex ideas. Perhaps it’s the very contradictions within the ideas the characters represent that give them power.

Does it represent a fundamental political incoherence? There are obvious echoes of fascism in the idea of the superhero, and Nevins takes care to point out that vigilante groups like the Ku Klux Klan are uncomfortably close to the superhero image, if only in their own minds. While he says in a note on page 319 that superhero characters “are not fascist,” in another note on page 327 he observes that there’s “something innately Fascist to superhero fiction and film, even if the superheroes … are vaguely moderate-left politically.” Still, I wonder if there isn’t also something inherently democratic in the typical superhero; or at least something in the superhero that requires democracy. The superhero is a character of remarkable gifts who does not seek to use them to rule. If they step outside some laws, they also (mostly) accept the legal process of courts and prisons. Usually, they act not out of a concern for themselves or the superpowered people around them, but out of a concern for the powerless — for the common people. They (mostly) can’t seem to change the world in which they act, in terms of changing governments or introducing meaningful new mass-produced technologies; but within that world they support law in a chaotic manner. Perhaps the best way to read the superhero is as pure narrative, but as is so often the case, the sense of meaning in a good narrative seems (to some of us, anyway) to encourage a symbolic reading of the story: to suggest hidden depths, whose articulation needs recourse to complex ideas. Perhaps it’s the very contradictions within the ideas the characters represent that give them power.

The Evolution of the Costumed Avenger doesn’t shy away from those ideas, or from the complexities and ambiguities in the development of the superhero. Nevins’ research is admirable and indeed astonishing in its depth, but more than that, he’s integrated a wealth of information and analyses into a complex but coherent story. It’s perhaps inevitable that one will have quibbles with some of his readings and conclusions, but fundamentally this book is a tremendous resource in not just the historical development of the superhero, but the analysis of the superheroic idea. Nevins has done important work, not just uncovering characters that deserve to be better-known but integrating them into the ongoing history of the superhero — and thereby also changing the common understanding of that history. Learned and thorough, The Evolution of the Costumed Avenger has much to teach any reader.

Matthew David Surridge is the author of “The Word of Azrael,” from Black Gate 14. You can buy his first collection of essays, looking at some fantasy novels of the twenty-first century, here. His second collection, looking at some fantasy from the twentieth century, is here. You can find him on Facebook, or follow his Twitter account, Fell_Gard.

Interesting and astute response to this intriguing book. When I saw in the subtitle that Nevins was going back “4,000 years,” my first thought was that must date from Gilgamesh — am I right in that assumption, or does he find proto-superheroes even further back than Gilgamesh and Enkidu?

Thanks, Nick!

You’re right, he starts with Gilgamesh and Enkidu. And he’s got some sharp observations about the relative superheroicness of the two characters!

I might have to hunt this book down. Could be a good companion read to Grant Morrison’s Supergods: What Masked Vigilantes, Miraculous Mutants, and a Sun God From Smallville Can Teach Us About Being Human, which I read last year.